The Architect: Meet the man who built the Warriors with a golden touch

Your teams. Your favorite writers. Wherever you want them. Personalize SI with our new App. Install on iOS or Android.

OAKLAND, Calif. — When ArnTellem took the call from Jim Harrick in the spring of 1997, he was intrigued. At the time, Tellem was one of the top NBA agents. Harrick, the longtime UCLA coach, had sent Reggie Miller his way a few years earlier. Now, he had another recommendation. “Someone terrific for you,” according to Harrick.

Tellem ran through the Bruins’ roster in his head. Two years removed from a national title, the team was loaded: Toby Bailey, Charles O’Bannon, Jelani McCoy. He became excited. "Okay, I’m listening," he told Harrick.

“His name is Bob Myers,” said Harrick.

Tellem was confused. Bob Myers? “Who,” he asked, “is that?”

*****

Now it’s the spring of 2015, and Myers—the GM of the Warriors, 2015 NBA Executive of the Year and a man you might not recognize if he sat next to you on an airplane—is playing one-on-one at the Golden State practice facility in Oakland, California.

At 41, Myers is the rare NBA executive who remains a hoops junkie. Many stop playing in their late 30s. Sam Presti, the Thunder GM and a former D–III player, gave up the game 10 years ago, concerned that an injury would inhibit his travel and scouting. Others burn out, or, like Steve Kerr, are failed by their bodies. Not Myers. He tries to play at least two to three times a week. Last year, during the playoffs, he and other Golden State staffers engaged in a “shadow playoffs” against opposing front offices as the Warriors advanced, taking on New Orleans, Memphis, and Houston, winning every series. He is not choosey. “He’ll play anyone, anytime, anywhere,” says good friend Mike Dunleavy Jr., who Myers represented as an agent before joining the Warriors. “Two-on-two, in the backyard, wherever.”

• MORE NBA: Lee Jenkins: The birth of the Warriors' death lineup

Neither has Myers eased up. Most men hit middle age and downsize, retreating to short courts and over-40 leagues. Myers? He likes to play full court one-on-one, on an NBA court, as part of a regular (and complicated) best-of-seven competition against Warriors player development coach Chris DeMarco, a 30-year-old, 6’7" former D–II player. On this afternoon, however, his opponent is a good bit shorter and a decade older than DeMarco.

That would be me. Like Dunleavy said, Myers will play anyone.

The game begins and Myers bends into a defensive stance. Other than his height—at 6’7" he’s tall enough to look like he played hoops but not so tall as to be intimidating—he appears resoundingly normal. Thin. Short, choppy dark hair. Large, expressive eyes. In conversation he’s self-deprecating and amiable, to the point that his wife, Kristen, sometimes wishes he weren’t so good at interviews, because the requests are constant.

Much like Steve Kerr and Steph Curry, Myers comes off as a regular guy, and deceptively so. To see him, presiding over a talented team—a guy who grew up in the Bay Area rooting for the Warriors, whose athletic career was by his own admission unspectacular, who loves chocolate chip cookies and PB&Js and playing pick-up hoops—is to be tempted to think, Hey, I could be that guy. And, from there, it’s only a hop, skip and an NBA title to deciding that, because you won your fantasy basketball league and possess a real eye for talent that, maybe—just maybe—you could do what Myers does. Surely, you’d have seen the promise to take Draymond Green in the second round or known to bet on Shaun Livingston but pass on Kevin Love. Same goes for navigating a maze of personalities and egos and decision trees to become one of the most successful, important, and widely-liked front office figures in the NBA. After all, isn’t this the new dream of so many young men today—not to become an NBA player but to manage them? How hard can it be?

It’s a beguiling thought, just as it’s beguiling to think, after going up 9-4 on Myers in the first game of one-on-one, that perhaps I’ve got Myers’s hoops game dialed in. That maybe he’s just playing for fun.

*****

Once upon a time, the path to becoming an NBA general manager was to play basketball, then coach basketball, then settle into a job BS-ing with other men who’d played and coached basketball. In the past two decades, however, the landscape changed. Daryl Morey, who holds an MBA from MIT and never played organized hoops, took over the Rockets in 2007. Cap specialists like Rich Cho, a lawyer and mechanical engineer, ascended in other cities. The wonkiest of them all, Sam Hinkie, a Stanford MBA who’d worked at Bain, apprenticed under Morey before getting the GM job in Philadelphia, where he engineered an unprecedented, well... something.

A set mold no longer exists. Business experience helps. So does legal expertise. A playing career is a plus, unless, that is, it becomes a minus—are you too close to the game, not analytical enough, not well-versed in the arcane rules of the collective bargaining agreement? As a result, almost anyone with brains and ambition can aspire to the position, and countless do. Attend the MIT Sloan Conference and you’ll see them, smart and young and motivated and hopeful. This (relative) democratization of the field has made the competition more fierce. There are still only 30 NBA teams. That means 30 jobs. That Myers holds one is both a testament to the changing culture and, in his eyes, because he is a serial self-doubter, something of a crazy fluke.

• Open Floor Podcast: NBA draft debates: Should Simmons go No. 1?

As a boy growing up in Alamo, Calif., Bob fell in love with the Warriors (he carries the ticket stub from his first game, on Jan. 15, 1982 against the Knicks, in his wallet). He played at Monte Vista High, down the road in Danville, but was, by his telling, not much of a player. He didn’t make varsity until his junior year, and didn’t start until he was a senior. Jeff Koury, his coach, is more generous, calling Myers, “a Dennis Rodman type who averaged more than 14 boards a game,” was adept at switching on defense (like his Warriors players now), and played with a near-manic intensity. “Every day you went to practice and your best player played harder than anyone else,” says Koury. “He self-coached the team through his effort and personality.”

Still, Myers fretted. He agonized over missed layups. Piled pressure upon himself. Says Koury: “You just wanted to shake him and say, ‘Do you realize how good you are?’”

Case in point: Myers’s defining moment—in his eyes—came his senior year, in the sectionals against San Ramon Valley High and Mark Madsen, the future Stanford star and Lakers reserve (and, later, a Myers client). Holding a one-point lead with seconds remaining, Monte Vista secured the ball and ran out the clock. Their fans stormed the court. Prematurely, it turned out. The refs deemed a Monte Vista player to have stepped out of bounds, and 1.5 seconds flashed back onto the clock. San Ramon inbounded to Madsen, who leapt and, in one motion, caught the ball and nailed a free-throw line jumper. Right over Myers, who was face-guarding him. This time, San Ramon students stormed the court, creating the rare double-storming.

“It was my last high school game,” recalls a glum Myers. “That was it. I had no place to go play after that.”

Gallery: When NBA head coaches were players

When NBA Coaches Were Players

Jeff Hornacek

Jeff Hornacek played 14 seasons between the Suns, Sixers and Jazz and was named an All-Star in 1992. Hornacek was fired midway through his third season as head coach of the Phoenix Suns (14-35) in 2016. The Knicks hired Hornacek, who holds a career record of 101–112 in 213 games as a head coach, on May 18, 2016.

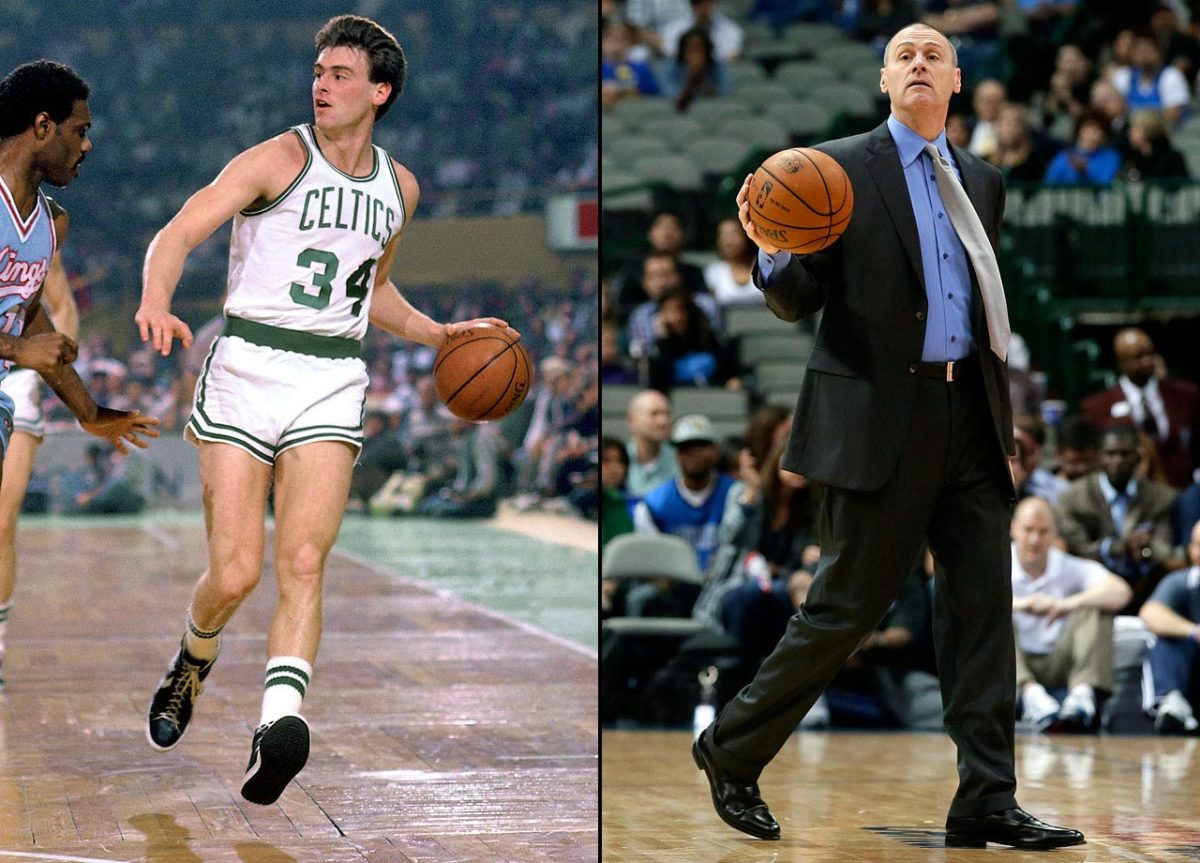

Rick Carlisle

Rick Carlisle has won a title as a player (with the 1985-86 Celtics) and coach (2010-11 Mavericks). He's coached Dallas since 2008 after spending two years with the Pistons and four with the Pacers.

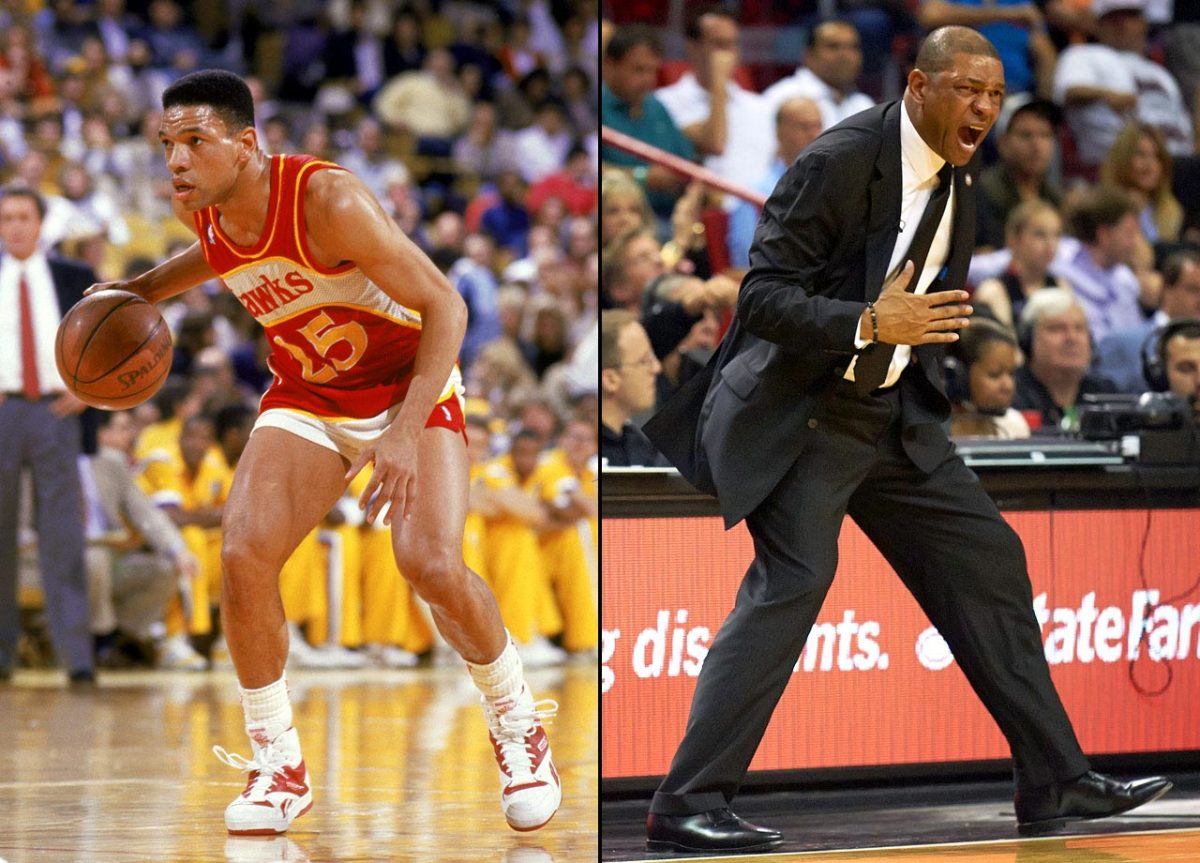

Doc Rivers

The Hawks picked up a reliable point guard when they selected Doc Rivers with the 31st pick in the 1983 draft. Rivers helped lead the Hawks to six playoff appearances in eight seasons, and he averaged 11 points and six assists in his 13-year career. He received his first crack at coaching with the Magic, in 1999, and won the Coach of the Year Award in his first season. Rivers later moved to Boston, where he won the 2008 title with Ray Allen, Paul Pierce and Kevin Garnett. He has been coaching the Clippers since 2013.

Jason Kidd

Kidd spent 19 years in the league, with the Suns, Mavericks, Nets and Knicks, before becoming Brooklyn coach just days after he retired in 2013. However, the 1994-95 Rookie of the Year, 10-time All-Star and 2011 champion with Dallas wore out his welcome with management and was traded to the Bucks after one season at the helm in which the Nets went 44-38 and lost in the Eastern Conference semifinals.

Steve Kerr

Kerr, a valuable role player who won three titles with Chicago and two with San Antonio, is the NBA's all-time leader in three-point percentage at 45.4. After distinguishing himself as a TNT broadcaster, Kerr became a hot coaching candidate despite lacking experience on the sideline. In May 2014, Kerr spurned the Knicks to become the Warriors' coach, which he led to a championship as a rookie coach.

Billy Donovan

Drafted in the third round (68th overall) of the 1987 NBA Draft by the Utah Jazz, and later waived, Donovan played just 44 games off the bench with the 1987-88 New York Knicks. After 19 years coaching the Florida Gators, the Oklahoma City Thunder hired Donovan as their next head coach for the 2015-16 season.

Fred Hoiberg

Drafted by the Pacers in the second round of the 1995 NBA Draft, shooting guard Fred Hoiberg played four seasons with Indiana, four with Chicago, and two with Minnesota. On June 2, 2015, the Bulls hired Hoiberg as head coach.

Tyronn Lue

The No. 23 overall pick in 1998, Tyronn Lue played for seven teams over 11 seasons in the NBA. The Cleveland Cavaliers made Lue their full-time coach after firing David Blatt on Jan. 22, 2016.

Earl Watson

Earl Watson played for seven teams over 13 seasons in the NBA. At age 36, he became the league’s youngest head coach when he replaced the Phoenix Suns' Jeff Hornacek on an interim basis on Feb. 1, 2016. After their season ended, the Suns made Watson their full-time head coach.

Luke Walton

The son of former UCLA and NBA standout Bill Walton, Luke was a favorite of Lakers fans during his nine-year stint as a selfless, hard-working reserve player. In his first season as an assistant coach for the Golden State Warriors, the team won the 2015 NBA Finals. On April 29, 2016, the Los Angeles Lakers hired Walton to become their new head coach after the Warriors' season concludes.

Scott Brooks

Though undersized at 5-foot-11, the scrappy Scott Brooks played 10 seasons for six teams and won a championship with the Rockets in 1994. He took over as head coach of the Oklahoma City Thunder one month into the 2008-09 season and was named NBA Coach of the Year in 2009-10. Brooks was fired by the Thunder following the 2014-15 season, after the team missed the playoffs for the first time in his six full seasons as head coach. On April 26, 2016, Brooks was hired to coach the Washington Wizards.

Nate McMillan

McMillan, a second-round pick of the SuperSonics in 1986, played 12 years in the NBA before his first head-coaching job with Seattle in 2000. McMillan then coached the Trail Blazers from 2005–12 before serving as a Pacers assistant.

An excellent student, he chose to attend UCLA. That spring, on a campus visit with his dad, he stopped in the athletic office to inquire about intramural hoops, or maybe crew to stay in shape. An exuberant, dark-haired young man greeted him. Steve Lavin, then the third assistant, had met Koury at a basketball camp and heard about the hard-working (and self-doubting) Myers. True to form, Myers asked about perhaps being the team manager. (“The confidence thing,” says Lavin). Think bigger, encouraged Lavin. Why not show up for preseason pick-up this fall, join conditioning, and at least try out?

Myers did and beat out 40 hopefuls for a walk-on spot. He was shocked and elated. He banged with the Bruins’ big men in practice, did whatever was asked. “A solid player and a better human being,” remembers Harrick. Fans loved him, in part because he was a no-name amidst big-time recruits. “He achieved near-mythical status because everyone desperately wanted to see him score at the end of the game,” recalls Ian McMahan, a student at the time who now treats pro athletes as a physical therapist. Eventually, Myers gained the nickname “Gump,” as in Forrest. There was Myers, a guy who averaged 0.3 ppg, on SI’s commemorative cover after the Bruins won the title in 1995, hoisting Tyus Edney after his full-court, game-winning layup. There was Myers on the Tonight Show, and riding on a float at Disneyland, and meeting President Bill Clinton, and taking lunches with John Wooden.

His junior year, Myers joined the rotation. In a career highlight, he scored 20 points in 22 minutes against Oregon State (he averaged 2.7 ppg that season and 1.4 as a senior). Still, such was Myers’s lucky-to-be-here mindset that he continued playing pick-up with other students at the Wooden Center, including on game days.

"Finally, someone said, ‘You can't do that anymore. You know you're actually playing, right?’"

*****

In the years since, Myers has noticed something about a certain subset of successful people in sports, and life: It’s not that they love to win so much as they really, really hate to lose. Steph Curry. Steve Kerr. Draymond Green, in particular. “You could be at a barbecue and a game of Monopoly breaks out, or you’re playing darts and you can tell the personality of the guy next to you,” says Myers. “You can tell, this guy doesn't care about winning or losing, and this guy does. And I think mine more derives from hating to lose. I think you either are that way or not.”

As Warriors GM, Myers is prone to what he calls “work benders”, grinding 18 hours a day for long stretches. The 2013 trade for Andre Iguodala was, “a 12-day bender,” for example. The start of free agency leads to another annual bender, during which Myers lives with his iPhone earpiece in, walking and fretting and talking. He’s fueled by something he can’t quite explain. “It’s the competitive aspect….feeling a responsibility to the organization, to the community. That drives me more than any drug, caffeine, Diet Coke, could.” Says Assistant GM Kirk Lacob: “He has immense focus. As soon as he starts a task, he wants to do the best job possible, and then he has the ability to move on and be diligent about the next task. To me, that’s an elite competitor.”

• MORE NBA: The Giant Killer: Draymond Green dares you to define him

This mindset was forged during Myers’s time with Tellem, who was so impressed with Harrick’s recommendation—“very smart, one of the best young men I’ve had in my program”—that he brought Myers on as an intern and then hired him once he graduated. At Tellem’s recommendation, Myers enrolled at Loyola Law School, attending classes in his beloved Warriors sweatshirt. His days were long: Arrive at Tellem’s office, work until 3:30, knock out his homework, then class from 6-10 PM. On game nights, he’d zip over to Staples to connect with clients. During one Staples visit, Myers was zoning out during a timeout when he noticed something unusual. One of the Laker Girls looked an awful lot like one of his little sister’s friends from high school. Upon closer inspection, it was Kristen and well, she looked…different. They’ve been together ever since.

From the start, Myers excelled at player relations. At UCLA, he became Harrick’s unlikely go-to guy—the sorta-geeky walk-on—when recruits visited. (“He had great integrity,” explains Harrick. “I could trust him.”). Myers hosted Baron Davis, hung with Paul Pierce and welcomed the Collins twins. Now, as a fledgling agent, he worked with Tracy McGrady and Jermaine O’Neal, helping with draft prep. He clicked instantly with Dunleavy, Jr., who says, “Bob was a big part of the reason I was with Arn.”

He’d always excelled at reading comprehension in school. Now, it translated to legal issues. “The interpretation is what I loved,” he says. “I lived in the gray area.” Writing was another matter. Tellem provided what he calls “a writing boot camp,” helping Myers to articulate arguments in print, whether in an email, or salary negotiation prep, or drafting a letter, or a brief analyzing the impact of salary cap rules.

• MORE NBA: Steph, Klay becoming NBA's best decoys vs. Cavaliers

Myers and Tellem grew close. The duo traveled Europe together, representing Pau Gasol and Danilo Gallinari. Foodies, they obsessed about meals, whether planning breakfast or a 1 AM snack after a day of meetings. They took late-night walks, winding through Treviso or Milan, engaging in what Tellem calls “Seinfield-ian philosophical conversations” about everything from politics to “what are we doing in our whole existence” to one of Tellem’s latest fixations, such as the identity of the genius who brought back Brussels sprouts. “They were like walking meditations,” says Tellem.

Occasionally the two discussed being on the other side, as GMs. It was an idea that lodged in Myers’s head, one he’d spoken about with Kristen as far back as their first dates: Run a team.

*****

In retrospect, it is easy to credit Myers’s run in Golden State to external factors: the unexpected brilliance of Curry, Kerr’s guidance, the ascendance of Green, Jerry West’s imprint and the tank job that netted Harrison Barnes. All are valid.

But part of Myers’s success stems from the fact that he’s the type of person who readily accounts for all this. His career is marked not by Jerry Maguire swagger but by humility. Myers doesn’t burn bridges. He doesn’t make power plays. “I’ve always felt like Bob was tremendously professional, really congenial and someone that is easy to talk to,” says Presti. Like many, Presti uses the word “earnest” to describe Myers. (Says Lavin: “That would be my headline: He’s Very Earnest”). Tellem praises Myers’ listening skills and empathy. “Bob is certainly analytical and understands the numbers, but at the end of the day it’s his personal qualities, and communicating, that matter. It’s all about the human capital, and managing those relationships.”

Which helps explain how he got the Warriors job. Myers’s people skills impressed Danny Ainge, the Celtics GM. Ainge in turn recommended Myers to Lacob when he bought the Warriors. And Myers impressed Lacob in an informal meeting, despite being a thirty-something agent with no management experience. Three months later, to Myers’s surprise, Lacob called back. “Were you serious when you said this might be something you'd be interested in doing?' Lacob asked.

Myers had negotiated nearly $600 million in contracts, representing close to 20 players. He didn’t think twice. In the spring of 2011, he took a pay cut to join a moribund franchise on a make-do deal as GM-in-training under Larry Riley.

Myers was supposed to apprentice for two seasons. Lacob elevated him before a year was up. His first 15 months were memorable. The Warriors acquired Bogut and drafted Klay Thompson, Harrison Barnes, Ezeli and Green. Then came the Curry extension, the Kerr hiring and, well, you know the rest.

• MORE NBA: How the summer of 2014 shaped this year's NBA Finals

Ask Myers about his tenure and he deflects credit, the unofficial pastime of Warriors. Only Lacob Sr. is an outlier. After he told the New York Times Magazine the Warriors were, “light-years ahead of probably every other team in structure, in planning, in how we’re going to go about things,” his front office peers started calling him “Buzz Lightyear” on text chains; Lacob took it well.

While the Warriors are famously collaborative, Myers makes the hard choices, often after soliciting dozens of opinions. Co-workers use phrases like “inclusive” and “empowering.” DeMarco remembers Myers asking his opinion when he was a video intern. “Not just to make you feel good but you can tell he’s really listening.” Kirk Lacob describes Myers as an “overcommunicator,” forever trying to gain as much information as possible. “The first year I met him, you couldn’t have a conversation with him because he was always on the phone,” says Lacob. “He’d walk around the office with his ear buds in. We’d joke that the only way to reach him was to call him.”

When Kerr took a leave of absence after back surgery this season, Myers called him every day, spurring Kerr to thank Myers in his Coach of the Year speech this spring. Said Kerr, fighting back tears: “Bob (Myers) went from being my general manager, a guy I worked with, to a guy I leaned on every day when I was struggling with my pain."

Last June, when the Warriors won the title in Cleveland, ending a 40-year drought, Myers sat and watched with a sense of relief. “There was no moment of celebration, just a handshake, like ‘We did it’,” says Kirk Lacob, who was sitting with Myers. That night, while Joe Lacob and the players celebrated, Myers could not. “Maybe a few hours,” he ventures, when asked how long he was happy. Says Kristen: “I wish he’d celebrate more, just enjoy it for a night or a moment.”

Such focus isn’t unusual in his line of work, where families and friends are routinely ignored for years in pursuit of one more film session. What is less common is Myers’s combination of introspection and anxiety regarding the matter. He worries about his worrying. “It’s dangerous for a GM to pour too much into it, and it’s very hard—my personality doesn’t allow me to not pour enough into it. I’m not worried about not caring enough. I’m worried about caring too much.”

Last year, he took a suggestion from West, a Hall of Fame worrier, and headed out for walks in the Oracle parking lot when he got too worked up during the playoffs. He tries to force himself to zoom out. He reads novels in season. He orders two newspapers on the road, including the New York Times or Wall Street Journal, to ensure he gets a “world view” outside sports; Myers can often be seen padding around in sweats at the road hotel, thumbing through a broadsheet. During home game timeouts, he reads the Journal—the print version, not on his phone—though he admits this becomes harder to do in the playoffs.

We fantasize about his job; Myers fantasizes about ours. He talks of one day teaching history or English and coaching high school basketball. Kristen doesn’t see it happening. “He can’t stop,” she says. “It’s just in him.” She says her dream is to attend a game as fans. “Get a big foam finger, have a beer, just watch.” He’s tried coaching his daughters’ teams but, “he was a little too serious,” Kristen says with a laugh. He is, above all, a striver. Concerned about staying close with Kristen when he got the Warriors job, he proposed and implemented a standing date night on Thursdays. He can never truly get away though; when the couple went to Hawaii last summer, a long-planned vacation, Myers woke every morning to answer a deluge of emails.

• MORE NBA: The little-known tennis book that shaped Steve Kerr

Myers has been better this year, he says, in part because of a perspective gained during the events of last year. That January, Kristen’s brother, Scott, embarked on a year-long backpacking trip with his wife, Chelsea. At 33, Scott believed in seizing life’s opportunities. He’d founded a company, “Live Your Legend,” aimed at helping people find work they love. His TED talk on the subject has 3.3 million views. Following his own advice, he and Chelsea sold their belongings to spend a year adventuring. In September, while ascending Mount Kilimanjaro, he was struck and killed by a boulder in a freak accident.

Bob and Kristen heard the news and spent the night crying together, then she left to be with her family. “Bob was amazing throughout,” she says. Steve Kerr called and emailed her family (“He’s an amazing man,” she says). When Chelsea returned, at Bob and Kristen’s urging, she moved into the Myers’s spare bedroom in their San Francisco home. Every month, the family—including the Myers’s two young daughters, Kayla and Annabelle—release balloons, sending them to Scott “in heaven.”

The tragedy changed Myers's outlook on life. “It helped me in a way to realize we don't control everything. I'm not so important that I can control the success of the Warriors.” He no longer paces the parking lot. He tries to sit in his seats during games, rather than the executive suite.

And he leans on his preferred outlet, one he calls “meditative in a way.”

*****

Which brings us back to our game of 1-on-1. Playing basketball, interestingly enough, is what helps Myers escape from worrying about the game.

Before we began, Myers had explained the rules: Alternate half court and full court games to 11 straight. Three dribbles allowed in the half court, starting outside the arc. Offensive rebounds are live, unlimited dribbles. Five dribbles in the full court game, starting at half court; no rebounds (the limitations were instituted because Myers kept running Luke Walton to death when they played). Both constructs favor length, decisiveness and shooting range. Myers has all three.

I’d solicited scouting reports leading up to the game. According to DeMarco, Myers prefers wing threes, has “no left hand”, uses a questionable half-spin move to the basket (“I think it’s illegal—probably a travel if you brought in refs”), but was a difficult matchup. Kirk Lacob compared Myers to Dirk Nowitzki (because he loves the midrange) and Enes Kanter (“though only on the boards”). Kerr was enthusiastic (“He’s good!”). All singled out a dominant trait: “”He’s super-competitive,” said DeMarco. When Myers and a team of Warriors staffers lost to a team of prisoners at San Quentin in 2014, Myers re-stocked the team, then put up a LeBron-like line of 43 points, 13 rebounds, five blocks, two assists and two steals in the win.

Most everyone around the Warriors plays ball. Myers loves the culture it creates. “It immediately breaks down these social barriers that exist when you're just having a cup of coffee,” he says. “You learn so much about somebody when you're playing basketball with them. You learn whether they’re selfish, unselfish. Fair, honest, dishonest. Teamwork, how competitive they are, how aggressive they are, how passive they are. I wish every job interview we had we could play one-on-one with the guy.”

Now, in our game, my lead evaporates. I take four dribbles on game point instead of three. Turnover. His ball. He comes back and wins. As the afternoon wears on, one game moving to the next, he provides play-by-play. “That’s just 6’7" against 6’1", he says upon bulling his way to the rim. When his runner rims out and I make for the corner, he castigates himself before I even hit the shot: “Missed layup leads to corner three!”

With his length, he blocks or changes many of my shots. Built like a distance runner, he never flags—it occurs to me he may be in better shape than at least one of his players. He’s physical but not dirty. He rarely if ever calls fouls (“That’s because you’re in the media,” says Kirk Lacob later, with a laugh).

After finishing me off, Myers sits courtside and we talk, as men our age do, about the inelasticity of our bodies. Myers wonders whether we all have a finite amount of jumps in us, about whether we could predict this stuff. “The guy, [Giannis] Antetekounmpo on Milwaukee? When he got drafted, his growth plates were still open, right? So, nobody really knew that. It would be interesting if we were looking at who to draft and you could measure their growth plates, and saw that he had more growth.”

He is fascinated by our fascination with his job. “People don't do it maliciously, but they often have opinions they think are warranted because they are GMs in their own mind,” he says. “But the percentage of the job that is a trade or a draft pick or free agent signing?” He smiles. “It's not, ‘I'm gonna call my buddy, and propose a trade on an email.’ ‘Hey, would you give me, you know, Adrian Peterson, for, you know, Drew Brees?’ It's anything but. It's the hours and hours and hours. It's not even making the decision, it's executing decisions that requires so much effort.”

For Myers, to be a GM is to exist in a world of rationalizations and cognitive dissonance. He spends all year aiming for the playoffs and, now that he's here, can only watch. One of the most powerful men in the organization—in the sport—rendered powerless. And yet he cannot take a break. You may think you want his job, and perhaps you do. Then again, does it sound like he’s having fun?

“Sometimes I think, I'm not sure if this is the job for me,” he says, leaning back in his chair.

“Really?”

“Yeah. We're doing fantastic, right? I don't enjoy it to the degree I should.”

“But isn’t that the way it is for everyone who's really good at their job? Part of the reason they're good at their job is because..."

“Maybe, yeah,” says Myers. “But I'm the albatross that's kind of dragging things down. And I don't want to be that way, but unfortunately we all bear our burdens. So sometimes I wonder, because most of the time in this job it's not what we're experiencing now [winning]. It’s dangerous the way my mind and body works when things are struggling. It's hard. It's almost like, man. I don't need that in my life, you know?” He laughs, ruefully. “It's almost too much, in a negative way. I'm not unhealthy or anything, but it's definitely, sometimes you wonder.”

Myers leans forward. Behind him, a crew is repairing one of the basket stanchions but otherwise the gym is empty. “Somebody asked me, ‘How are your players going to be motivated to repeat? And I said, ‘I don't know, but I'm hopeful we have guys, I think we do, that just hate to lose." And it doesn't matter if you have five championships, or one, or two. You don't want to lose, You want to keep winning and winning and winning.”

• MORE NBA: Golden Season: Looking back at Warriors' 73–win season

He continues. “I mean. I don't know any other way. Like, okay, the job's over now, we won however many games, we won a championship, now you're done? I don't even know how that works. I wouldn't even know what that looks like.”

He pauses. Runs his hand through his hair. “I just don't understand that. Maybe that's part of my problem.”

A few minutes later, Myers heads in toward the locker room. Within the month, the Warriors will knock off the Rockets in the playoffs, then complete a stunning comeback against the Thunder, after which Myers will stand outside the Warriors locker room, looking somewhere between bewildered and giddy. A week later, with the Warriors up 2-0 on the Cavs, we talk by phone on the eve of Game 3. Myers cautions against optimism, worried that everyone is anointing the Warriors too early, and that Cleveland is a tough place to play.

But for the moment, here at the practice facility after our 1-on-1 game, he’s just a guy in sweaty hoops gear holding a bag of chocolate chip cookies, on the heels of a good run. A guy who just balled out. A guy who did something better than win.

A guy who didn’t lose.