Billy Ray Bates’s ongoing struggle to sort out life after basketball

It was the mid-1960s and he wanted to play basketball, Billy Ray Bates did, but he had a problem: There was no hoop outside the family’s home in tiny Kosciusko, Miss., and no money to buy one. Billy Ray was eight or so. His father had just died. His mother worked the cotton fields of a large estate. So Billy Ray hatched a plan. He would pick soybeans and chop cotton, save his wages and buy a rim himself.

Sure enough, he worked for weeks, and when he had enough cash he bought the goal and mounted it on a pole above a dirt patch. Giddily, his brother took the first shot and swished it through. But in his haste, Billy Ray hadn’t cleared the patch. The ball flitted through the net, landed smack on a nail and popped. Billy Ray didn’t have the money to replace it.

Welcome, in miniature, to the basketball career of Billy Ray Bates. It began packed with promise, an impossibly athletic guard who took the back roads but arrived in the NBA, playing to rave early reviews. Then, owing to mostly his own carelessness, it ended, punctured and sadly deflated.

• SI’s Where Are They Now issue: This year’s stories, all in one place

Though I’d heard this story from Bates years ago, he repeated it to me in a raspy voice by phone this spring, stopping to cackle and add phrases like “Now get this” and “The thing of it is.” For some time we had arranged to meet in New Jersey and reconnect. But as the date neared Billy Ray’s then wife, Beverly, said resignedly, “I think he might be in L.A.” A loose plan to meet on the West Coast fell apart when Billy Ray, at the last minute, left for the Philippines. Once he was back in California we made a date to Skype, but then his Internet service failed him. Finally, we settled on a few phone calls.

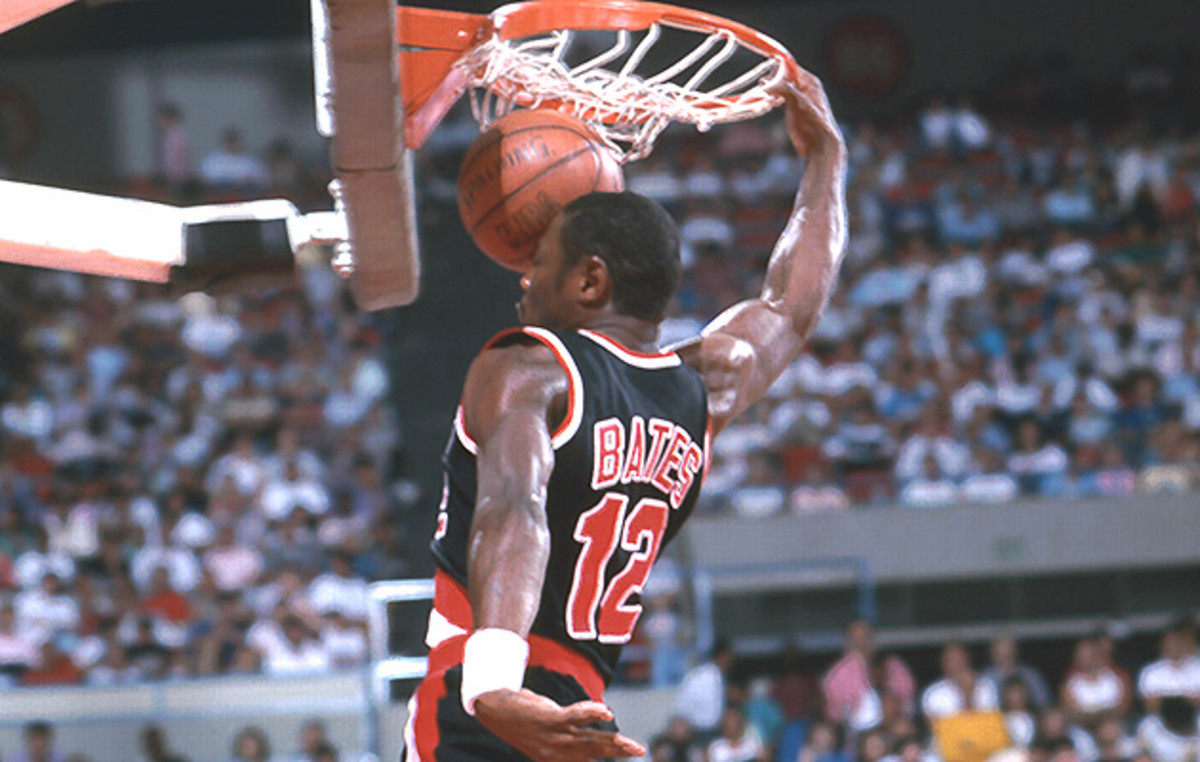

Bates is 60 now. He can still dunk. Or could until he had hip surgery. “Now, I am definitely retired as a basketball player,” he says. “And I don’t get out of here much.” Here is a small apartment in Anaheim, provided to him through the Illumination Foundation, a non-profit that helps Southern California residents find stable housing.

Ask him how he’s doing and he begins by laughing richly, saying, “I’m still alive, so there’s that.” But then comes a tale, not easy to follow, that wends from a blown annuity to an alcohol rehab center to a stint in jail to a padlocked storage unit. Finally, Bates summarizes, “A lot has happened—know what I mean? I’ve made a lot of mistakes, but I keep pressing forward.”

It’s all a reminder: If one of the happiest sports tropes is the unknown who becomes a star, one of the commensurately saddest is the star who becomes an unknown.

It was the winter of 1980 and the Trail Blazers were slogging through a forgettable season. The roster thinned by injuries, Portland needed an infusion of scoring. After some spirited front office debate, the team offered a 10-day contract to an incorrigible gunner who’d been tearing up the CBA.

If Billy Ray Bates’s name was something straight from pulp fiction, so was his backstory. The eighth of nine siblings, he was born in 1956, but it might as well have been 1856. He grew up in a shack without indoor plumbing. Conventional items like books and hairbrushes were considered luxuries.

But as a basketball player he was gifted almost beyond reason. A sort of proto-LeBron, Bates was 6' 4", with a convex chest, huge hands—“them big meat hooks!” he calls them proudly—and muscles that appeared to be making a jailbreak from his skin. He was strong enough to post up, skilled enough to rain jumpers from 30 feet and athletic enough to dunk with disregard both for defenders and the laws of physics.

A prodigious scorer at Kentucky State—where he came within a few semesters of graduating despite reading at an elementary school level—Bates was the Rockets’ third-round pick in 1997. He didn’t make their roster and pinballed around the CBA. While he racked up points early and often, he was also dogged by what are euphemistically called “character questions.” Here was a player with a sizable risk/reward ratio.

The 76ers brought Bates into camp in 1979. Each year coach Billy Cunningham had his players run one mile. Andrew Toney had won the previous year with a time of 5:30. Bates ran a 5:15. Afterward he bragged that he was hung over and had been in the company of multiple women the previous night. Philadelphia cut him, and he returned to the CBA.

In 1980, though, the Blazers were clinging to the eighth playoff spot in the West when they signed Bates. General manager Stu Inman and head scout Bucky Buckwalter overrode the coach, Jack Ramsay, who didn’t take kindly to ungovernable talents. After keeping Bates on the bench a few games Ramsay inserted him for some garbage time against the Bucks. Bates erupted for 14 points in the fourth quarter. The following night in Chicago, Ramsey grudgingly put Bates in earlier. He dropped 26, scoring on all manner of moves. In March—having been in the league less than a month—Bates was named the NBA’s Player of the Week.

Gifted as Bates was at putting a ball though a hoop, he was comparably skilled at winning fans. By popular demand, he would stay on the Memorial Coliseum court after games and, while his teammates were changing to go home, put on dunk displays for the crowd. He gave out his phone number to anyone who asked. When fans called his name during games, he would, reflexively, turn around and wink. He wasn’t cultivating an image; he simply knew no other way. “Man,” he says now, “I was just being me.”

By chance, Pulitzer Prize winner David Halberstam was following the Blazers during the 1979–80 season, writing the classic book Breaks of the Game. He, too, was seduced by Bates. “He had such tremendous athletic ability that once he got in the open court you knew something would happen,” Halberstam told me. “But most of all, I remember his sweetness. He had such a humanity to him.”

Bates was a gazillion cultural miles from hyper-rural Kosciusko (population today: 7,400), in a place with a modest African-American population. And yet Portland was, in some ways, the ideal place for his breakthrough. More of a large town than a small city—especially in the early ’80s—it has always appreciated quirk and embraced the underdog. Playing a few miles from the headquarters of a startup named Nike, Bates, too, was a local product gaining national prominence. He wasn’t just a legend; he was a legend everyone wanted to be part of.

Bates’s teammates were astonished equally by his talent and his lack of sophistication. He drew chuckles when he arrived for his first game dressed in his uniform. (He says he’d changed at the hotel, never having played in a locker room big enough to accommodate an entire team changing at once.) Bates recalls that when he introduced himself to Bill Walton, the team’s star, he gushed, “Hey, Big Red, I’m Billy Ray Bates!” Walton, he recalls, just grinned and shook his head. Similarly, in Breaks of the Game, Halberstam writes that Bates heard that a teammate, Calvin Natt, was from the South and might be a kindred spirit. “Did you grow up eating up squirrel and possum?” Bates asked excitedly. Natt erupted in laughter.

The Blazers made the playoffs that year; Bates averaged 25.0 points in the three-game series against the SuperSonics (which ended 2–1 in Seattle’s favor). CBS panned to fans holding up cardboard signs: BATES FOR PRESIDENT. Says Mychal Thompson, who played with Bates in Portland, “Billy Ray was like a comet that came out of nowhere.”

When Bates returned the next season, he was maddeningly erratic. By multiple accounts (including his own) he was losing himself in the wilderness of the night hours and drinking heavily. One former teammate recalls that Bates would drain six-packs before games. Ramsay complained that Bates kept forgetting plays. Some games, his efforts were vacant. Others, he dominated. He had eight points one night in Houston; two days later, at Dallas, he poured in 35 in 25 minutes. He put up a career-high 40 against the Clippers three games after scoring four. Then, as if to tantalize, he averaged 28.3 against the Kansas City Kings in another first-round loss, still the franchise playoff record.

• From the Vault (1981): Blazers finishing strong a year after Bates took off

After an uneven 1981–82 season, the Blazers waived Bates. He was picked up by the Washington Bullets but lasted only two months. In April ’83 the Lakers signed him. (He recalls that Magic and Kareem laughed at his Jheri curls.) When his 10-day contract expired, so, in effect, had his NBA dream. “Basketball stopped being fun by then,” he says.

Bates had a second act in the Philippines, again as much on account of his irrepressible personality as his freelancing game. In his excellent 2010 book Pacific Rims, Rafe Bartholomew wrote extensively (and hilariously) about Bates. In six seasons, playing mostly for the Crispa Redmanizers, he averaged 46.2 points—that’s not a typo—and had his own signature line of shoes, called the Black Superman. Teammates also recount that he downed whiskey the way they consumed beer. One drunken night, Bates picked up a car by its bumper and did a set of curls.

By the late ’80s, having broken various sobriety pacts with his team, Bates left the Philippines. He played in a few more games in a few more outposts—Uruguay, Switzerland—but for all intents, the ride was over. By Bates’s own admission, he was lost, broke and, maybe most significantly, a half-season short of an NBA pension. The comet in the basketball cosmos no longer lit up the sky.

My first job out of college was working for the Trail Blazers’ fan magazine, Rip City. This was the mid-’90s, the height of Blazermania, corresponding with a series of teams that came close to winning an NBA title. Still, for all the current excitement, I kept hearing references to this cult figure from the ’80s, Billy Ray Bates. You saw his number 12 jersey everywhere. When fans wrote in for contests they were asked to list their favorite Blazer; Bates would draw as many mentions as any player this side of Clyde Drexler.

Everyone around town had a Bates story. A drinking story. A woman story. One employee I knew at Nike claimed to have taken Bates’s driving test for him. All this buzz for a guy who’d played only 168 games in Portland more than a decade earlier. Yet no one seemed to know what had happened to him.

I finally tracked down Bates in South Jersey, where he was living with Beverly and two stepdaughters. He had just left a job gluing leather handles onto briefcases for $7 an hour. By then I was living less than an hour away, in Philadelphia. I profiled Bates for Rip City after we spent a rollicking day together. Almost 40 years old and clad in jeans, he put on an impromptu dunking exhibition at a gym. He ate an entire pizza. We watched VHS tapes of him throwing down over players like George Gervin and Darryl Dawkins. Mostly, he filled my notebook with quotes like, “I get tired of being patient.”

Shortly after the story came out I received a package that, judging from the handwriting, had been sent by a child. Bates had signed a copy of the magazine. The inscription: “To Jon, my best friend. Fly with me. The Black Superman. From, Billy Ray Bates #12.”

We stayed in touch and got together every month or so. Sometimes it was for a specific purpose. Once, he asked for help drafting a letter to Zelda Spoelstra (the aunt of current Heat coach Erik), who ran the NBA’s players Assistance Program. Another time, he needed a ride to physical therapy. One day he called claiming that he’d lost his basketball shoes and asked me to buy him a new pair.

Even in his early 40s, he insisted that he could still play in the NBA. “The only player out there better than me is Michael Jordan,” he declared over and over. Not unreasonably, he thought the Blazers still owed him for all he’d done to help the franchise. Less reasonably, he wanted that dispensation to come in the form of a three-year, $1 million contract. Here’s what Halberstam said to me at the time: “A lot in the world was hard for him, coming from where he did. In many ways, he just didn’t have the tools to make it in a post-industrialized society.”

Eventually I moved to New York City and the calls came less frequently. By 1998, I hadn’t heard from Bates in many months. When I left a voicemail for him at his home in Sicklerville, N.J., his stepdaughter called me back. “You didn’t hear? Billy’s in jail for trying to rob a gas station.”

Polluted with alcohol and armed with a three-inch knife, Bates, along with two accomplices, had held up a Texaco in Gloucester, N.J. He was arrested within the hour, found passed out in the bushes behind the station. According to the police report, he had $7 in his pocket. As Bartholomew put it, “This had to be one of the world’s all-time telegraphed passes; it was the rock bottom Bates had been approaching for 15 years.”

Until his parole in March 2005, Bates served nearly five years at Bayside State Prison in Leesburg, N.J., for first-degree aggravated assault and second-degree assault. He was back in Bayside 18 months later for violating his parole after cocaine showed up in his drug test. (He has asserted recently that his girlfriend at the time gave him cold medicine that contained codeine.) He served another three months and 24 days.

• From the Vault (1999): How (and why) so many athletes go broke

Out of prison since 2008, Bates has struggled, unable to find a steady job. He says that he drinks on occasion, but “I ain’t an alcoholic and I ain’t drugging.” Friends encourage him to return to Portland, where he remains a cult hero, but he hasn’t been back since the mid-’90s. “Just trying to pay for the airfare,” he says, “would be a challenge.” Asked what makes him proudest, he hums meditatively. “You know what I would say? That for all I’ve been through, I haven’t changed. Didn’t matter if I was drinking champagne in a limo or not knowing where I was going to live, I always stayed true to how I was raised.”

A few years ago he was invited back to the Philippines to be inducted into the Philippines Basketball Association’s Hall of Fame. He was supposed to stay for four nights, but the ticket was open-ended. Bates being Bates, he charmed his way into a skills coach job with a local team and his presence inspired a relaunch of his signature shoe line. Bates being Bates, he lost his money, was arrested for throwing a rock at a car at 2 a.m. and, according to The Philippine Star, “was linked to a scandalous incident involving a transvestite he had mistaken for a woman and brought to his unit.” When he finally left the country more than a year later, he was reportedly escorted to the plane by Bureau of Immigration agents.

Bates lives alone now and says he’s happy. He also has a plan. He wants to take courses at nearby Argosy College and get a degree. (“It’s never too late!”) He’d like to buy a car or a truck and then get a full-time job. He’s hoping to interest prospective sports filmmakers in a documentary. “People will know what happened to me and hopefully that will lead to a movie deal,” he says.

Then there’s his autobiography. Having worked at it off-and-on for years, he says he has more than 100 handwritten pages. And while he has more chapters to write, Bates has settled on a title: Born to Play Basketball.