Malcolm Gladwell Q&A: The granny shot, Wilt Chamberlain and more

Your teams. Your favorite writers. Wherever you want them. Personalize SI with our new App. Install on iOS or Android.

In the first three episodes of “Revisionist History,” a new podcast series, best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell tackles, in order, a 19th century painting, the Vietnam War, and underhanded free throw shooting. That range of topics is as Gladwellian as it gets. But, as always, there’s an underlying point to each of these far-flung mental journeys.

In the free throw shooting episode, released this week, Gladwell explores Wilt Chamberlain’s flirtation with the underhanded style. The method, also called “granny style” shooting, was favored by Rick Barry, a career 89.3% free throw shooter, and it helped Chamberlain shoot a career-best 61% from the line in 1961–62, the same season he sank 28 of 32 free throws in his record-setting 100-point game. Much to Gladwell’s dismay, however, Chamberlain reverted to traditional foul shooting, his percentages predictably plunged again, and he later admitted that he felt “like a sissy” when he shot underhanded.

Gladwell’s underlying point is clearly stated: Why would a Hall of Famer reject a proven, simple solution to his most obvious flaw when another Hall of Famer used the exact solution to historically great effect? And, in turn, why have modern players largely followed in Chamberlain’s footsteps rather than Barry’s?

The Chamberlain/Barry dichotomy leads naturally into an exploration of high threshold versus low threshold personalities. In the simplest sense, a high threshold personality (like Chamberlain) is more likely to allow a crowd to dictate his behavior, while a low threshold personality (like Barry) pursues the preferred course with less regard to social cost. By the end of the episode, Gladwell finds himself “admiring” the polarizing Barry’s willingness to shun hecklers and groupthink as he perfected the method of foul shooting that ultimately maximized his ability and value.

• No shortage of bigs on free agent market | Who wins KD sweepstakes?

Of course, the modern NBA is loaded with enough poor free throw shooters that the “Hack-a-Shaq” strategy of intentional fouling is one of the league’s longest on-running debates. Commissioner Adam Silver even told reporters during the Finals earlier this month that the league was “not far away” from reforming its approach to the issue. Still, no NBA player has yet been willing to attempt shooting underhanded, although Pistons coach Stan Van Gundy said center Andre Drummond was “open” to the idea after shooting a career-worst 35.5% from the line on the season and getting hacked off the court repeatedly during the postseason.

Should Drummond break through the stigma and groupthink to take the plunge on a better approach? How might the Pistons and his fans help his effort? And should the NBA reassess its entire approach to fouls?

SI.com posed those and other NBA-related questions to Gladwell in a telephone interview on Tuesday. The following has been edited for length and clarity. Disclosure: SI.com’s “Open Floor” NBA podcast, like Gladwell’s podcast, is affiliated with the Panoply Network.

Ben Golliver: You noted that granny style shooting is generally viewed as a “shameful” approach that, in the Chamberlain example, runs counter to a macho sensibility. Do you think the height of the players who are often poor foul shooters is a contributing factor?

Malcolm Gladwell: I’m sure that’s part of the complicated psychology, except that you’re standing out even more when you’re missing free throws in crucial situations. When DeAndre Jordan gets yanked at the end of a playoff game, he’s the focus of everyone in the entire arena. It’s not like the strategy they currently follow doesn’t have them standing out. They’re standing out now for the worst possible reason: They’re incapable of doing fundamental and relatively straightforward basketball acts.

Shaquille O’Neal, one of the greatest players in the history of the game, is now memorialized for his failure: Hack-a-Shaq. You can’t stand out more than when you have a term named for you! If height is a part of their psychology, it only deepens the irrationality, it doesn’t explain it.

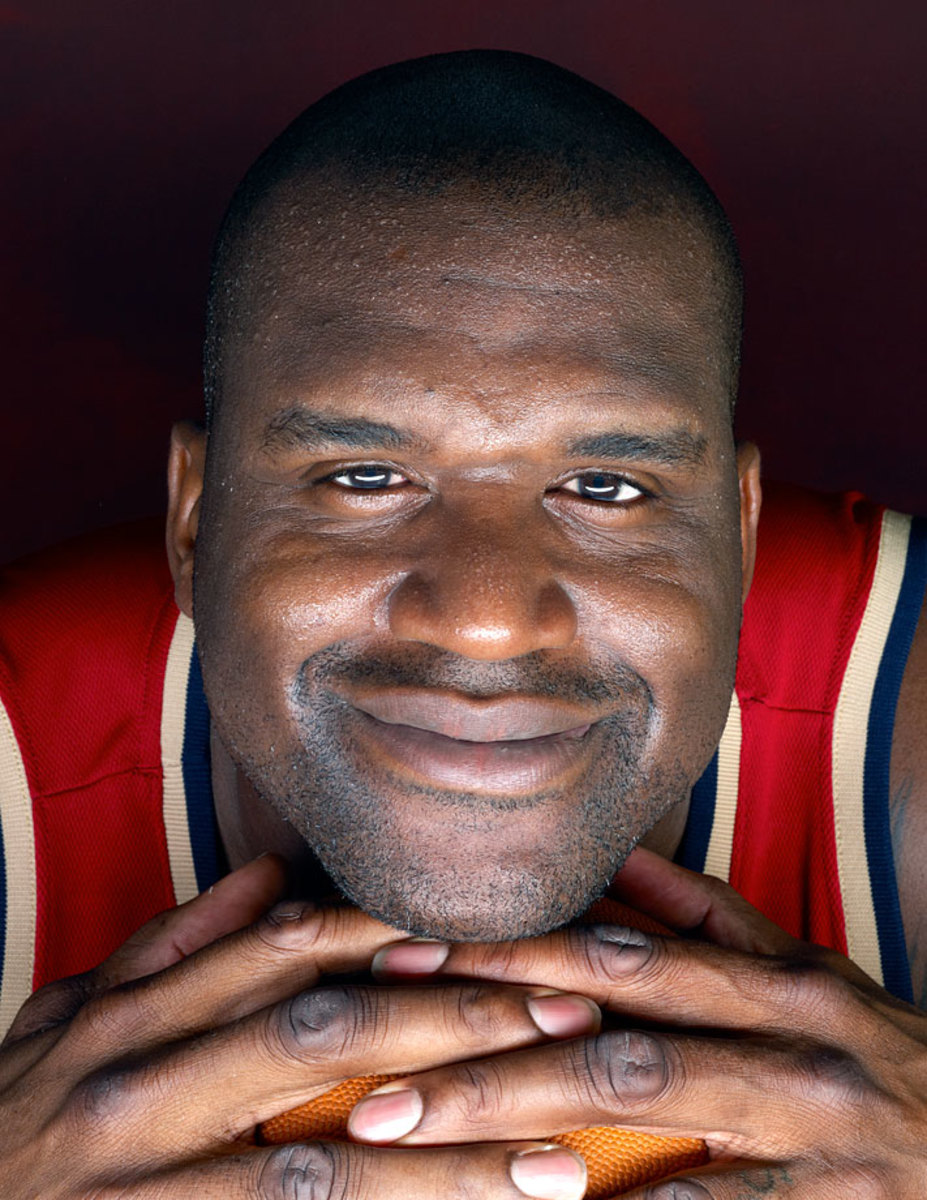

• Rare photos of Shaquille O'Neal throughout the years

Rare SI Photos of Shaq

Shaquille O'Neal

1991

Shaquille O'Neal

1992 SEC Tournament

Shaquille O'Neal

1992 NCAA Tournament

Shaquille O'Neal

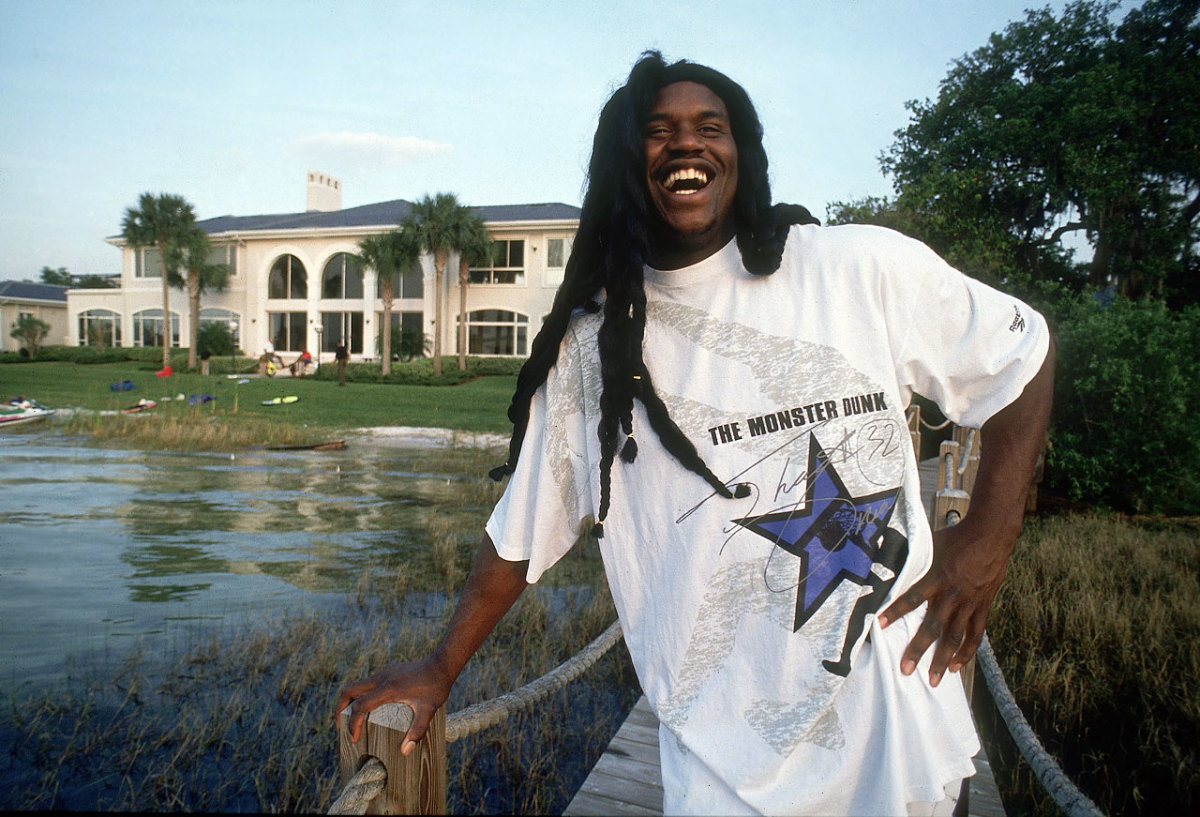

1994

Shaquille O'Neal

1994

Shaquille O'Neal

1994

Shaquille O'Neal and Charles Barkley

1994

Shaquille O'Neal and Patrick Ewing

1994

Shaquille O'Neal

1995

Shaquille O'Neal and Michael Jordan

1995 NBA Eastern Conference Semifinals - Game 3

Shaquille O'Neal and Hakeem Olajuwon

1995 NBA Finals - Game 2

Shaquille O'Neal and Michael Jordan

1996 NBA Eastern Conference Finals - Game 4

Shaquille O'Neal

1996

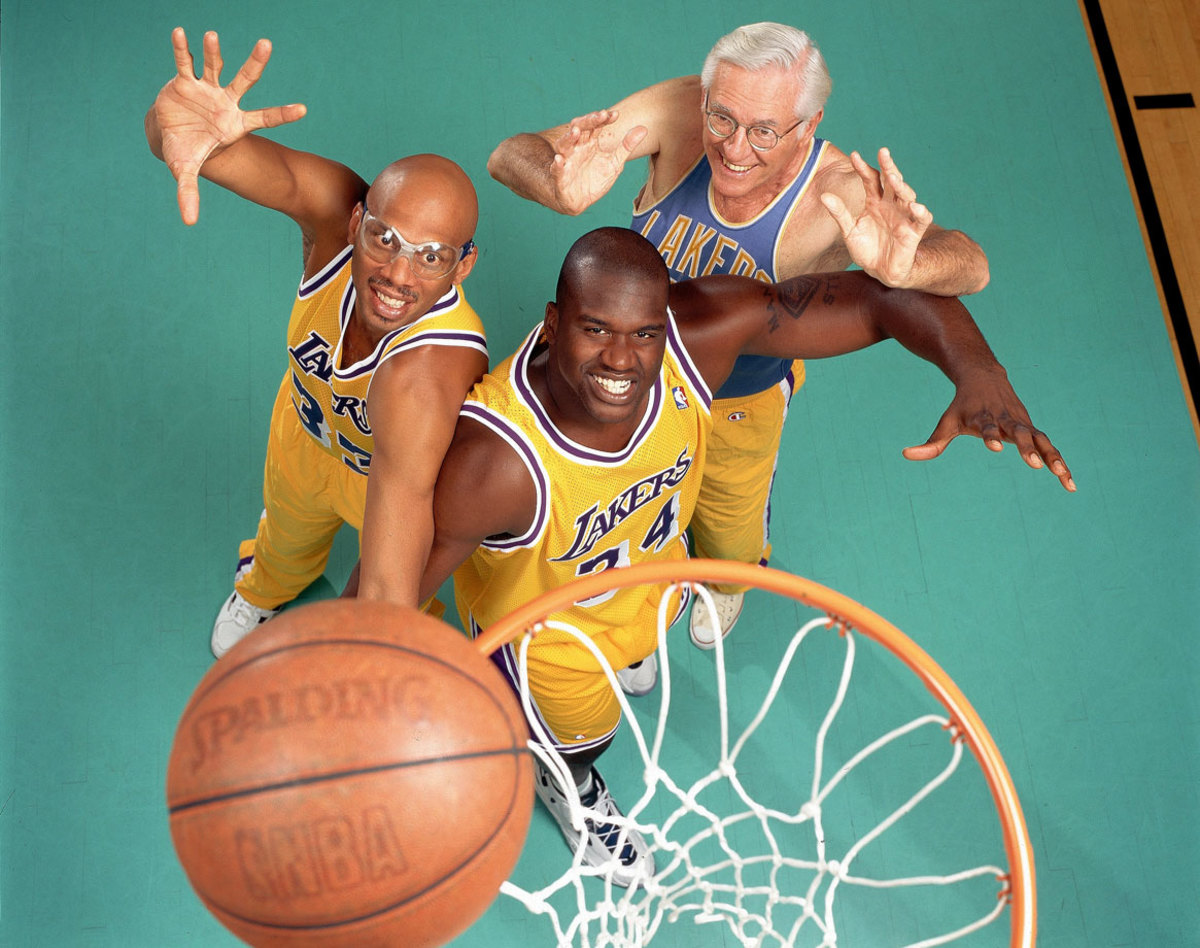

Shaquille O'Neal, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and George Mikan

1996

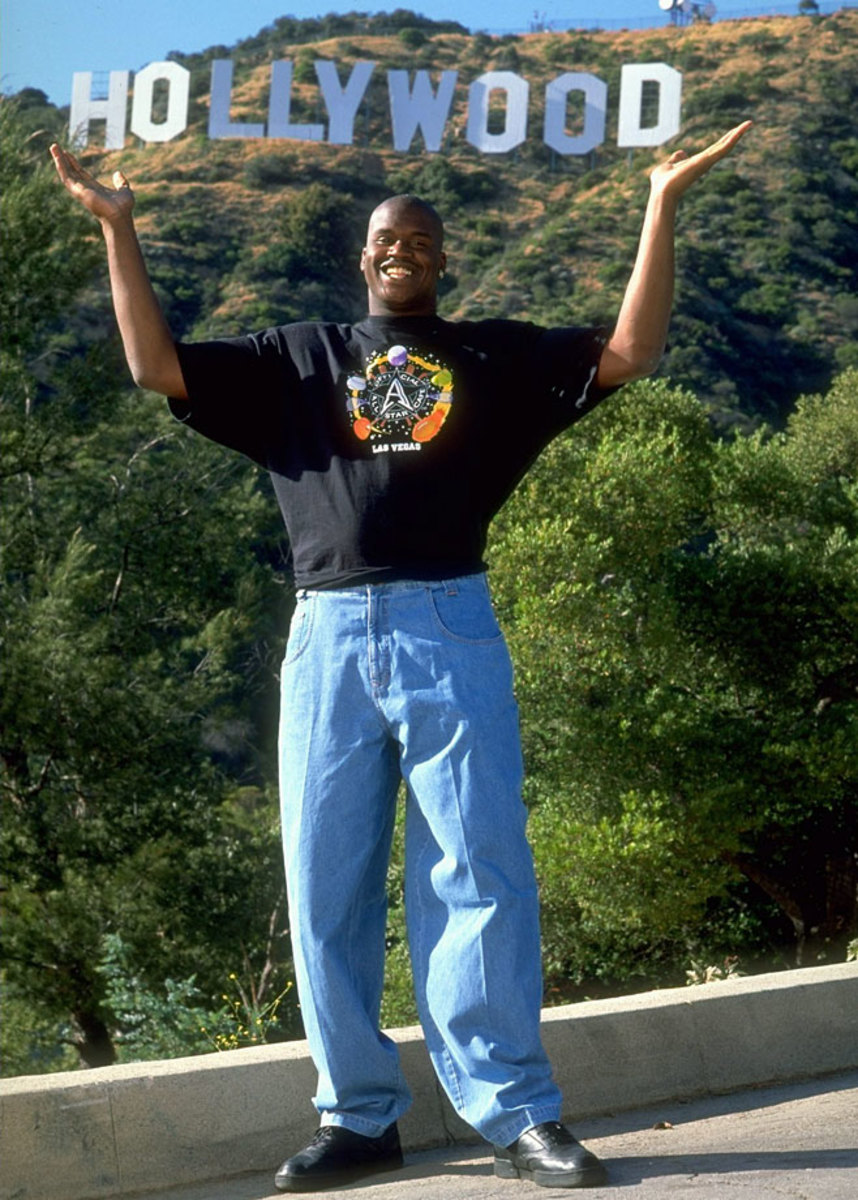

Shaquille O'Neal

1997

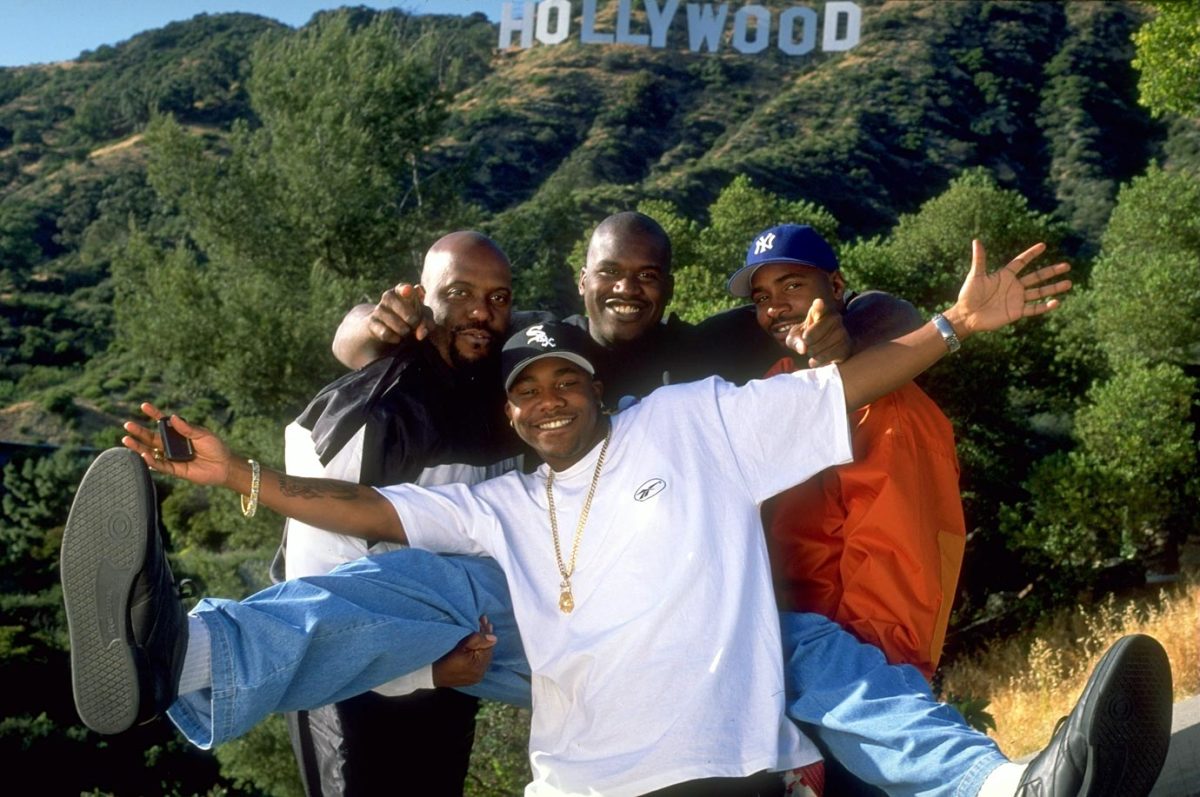

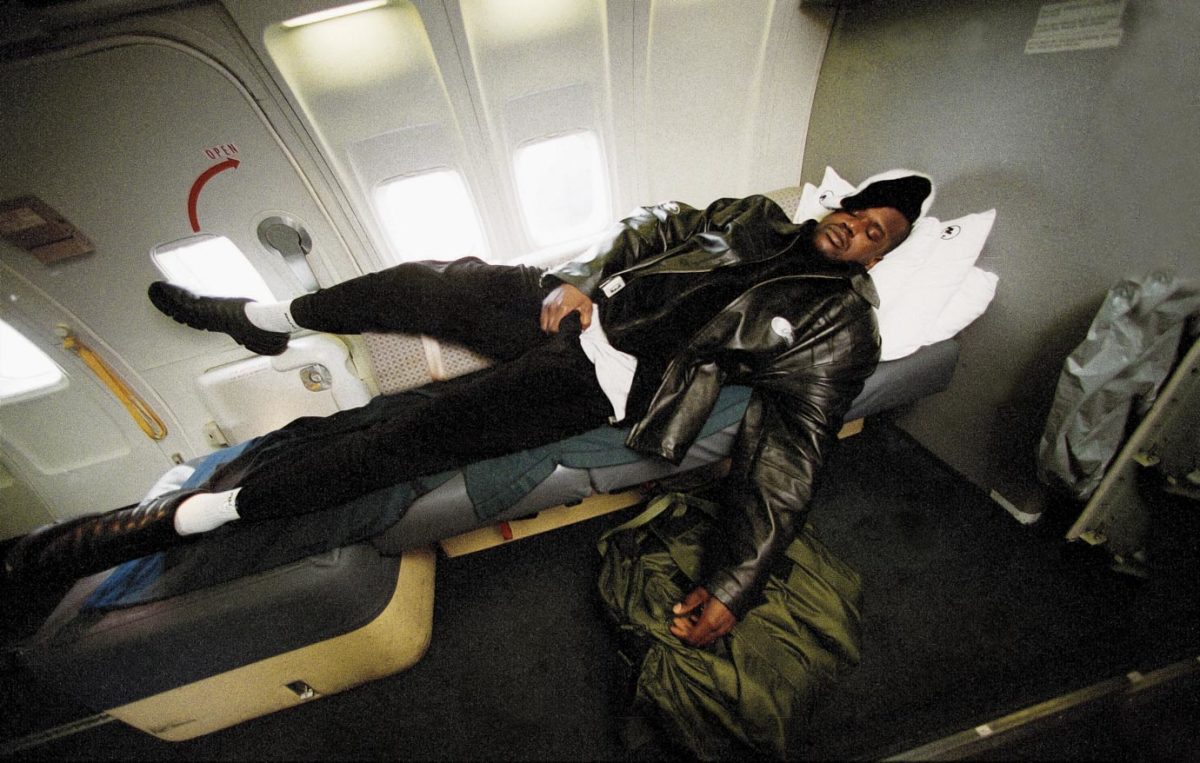

Shaquille O'Neal with friends Jerome Crawford and Andre Spellman

1997

Shaquille O'Neal with friends Jerome Crawford, Kenny Bailey and Andre Spellman

1997

Shaquille O'Neal

1997

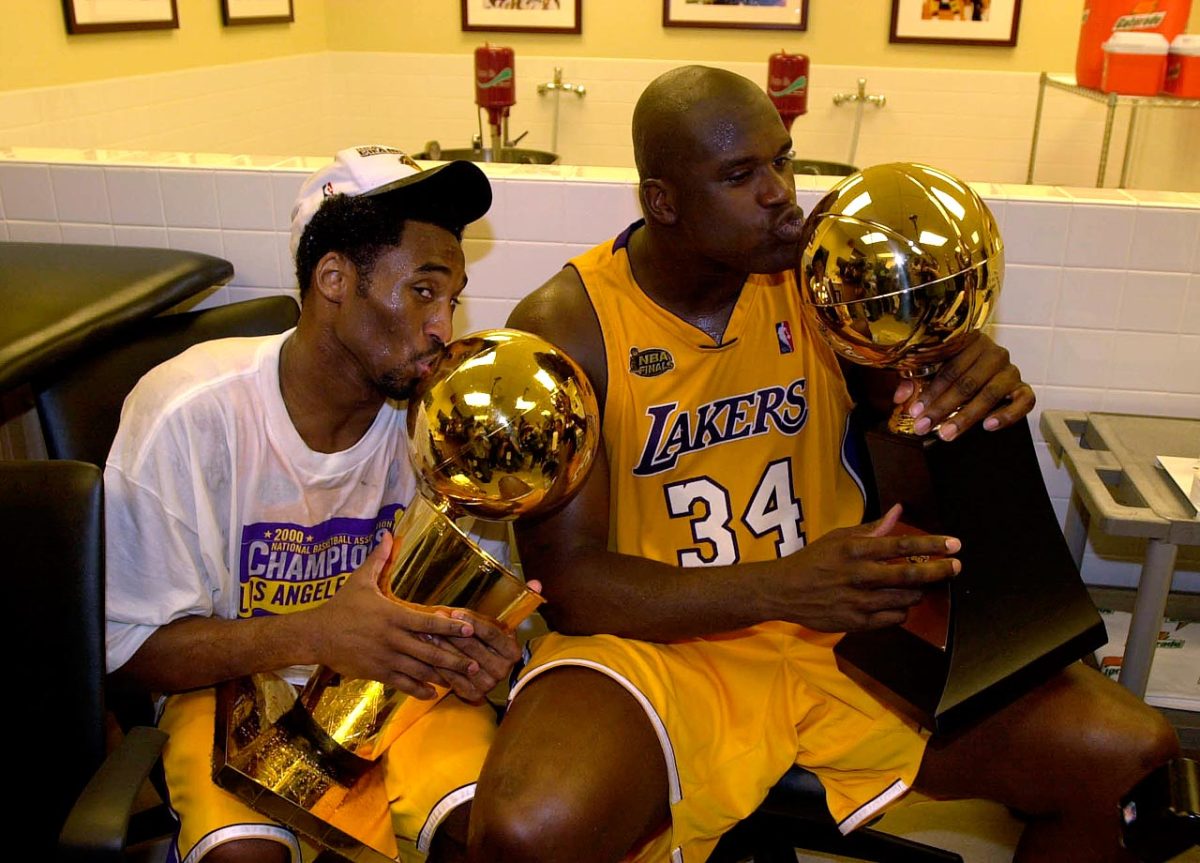

Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O'Neal

2000 NBA Finals - Game 6

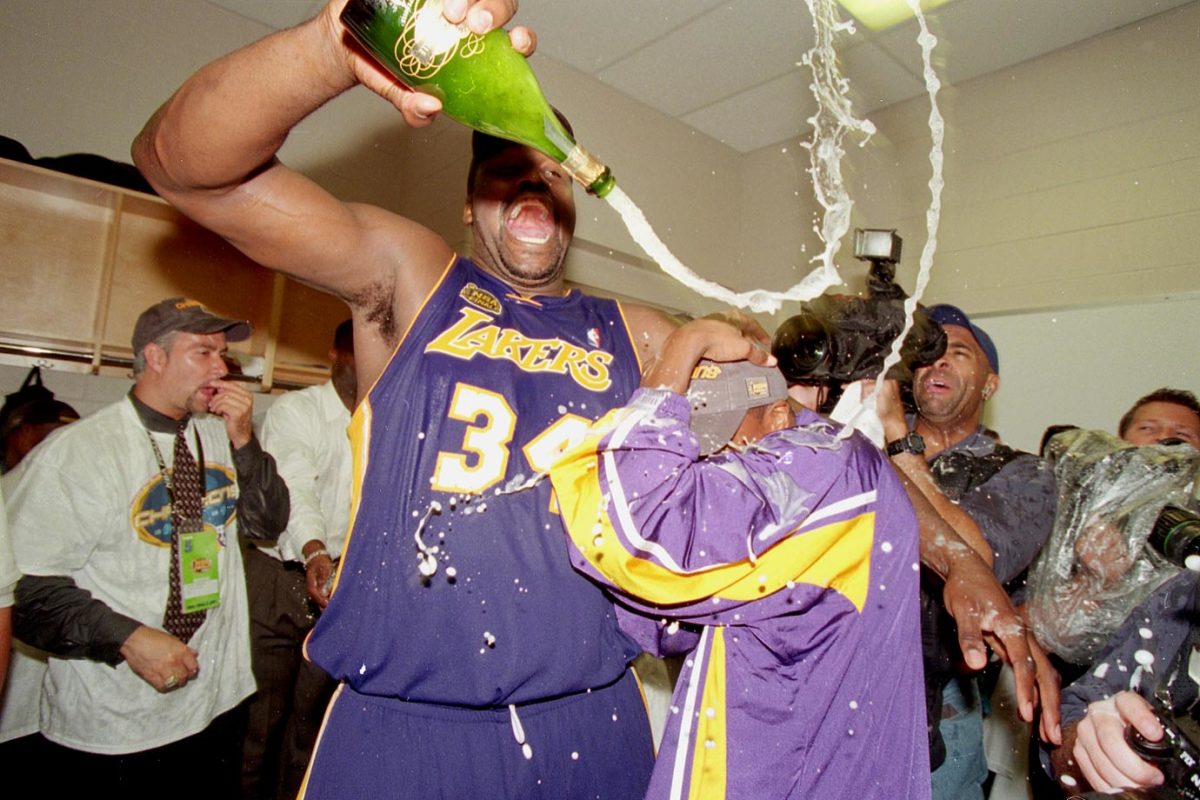

Shaquille O'Neal and Chris Tucker

2001 NBA Finals - Game 5

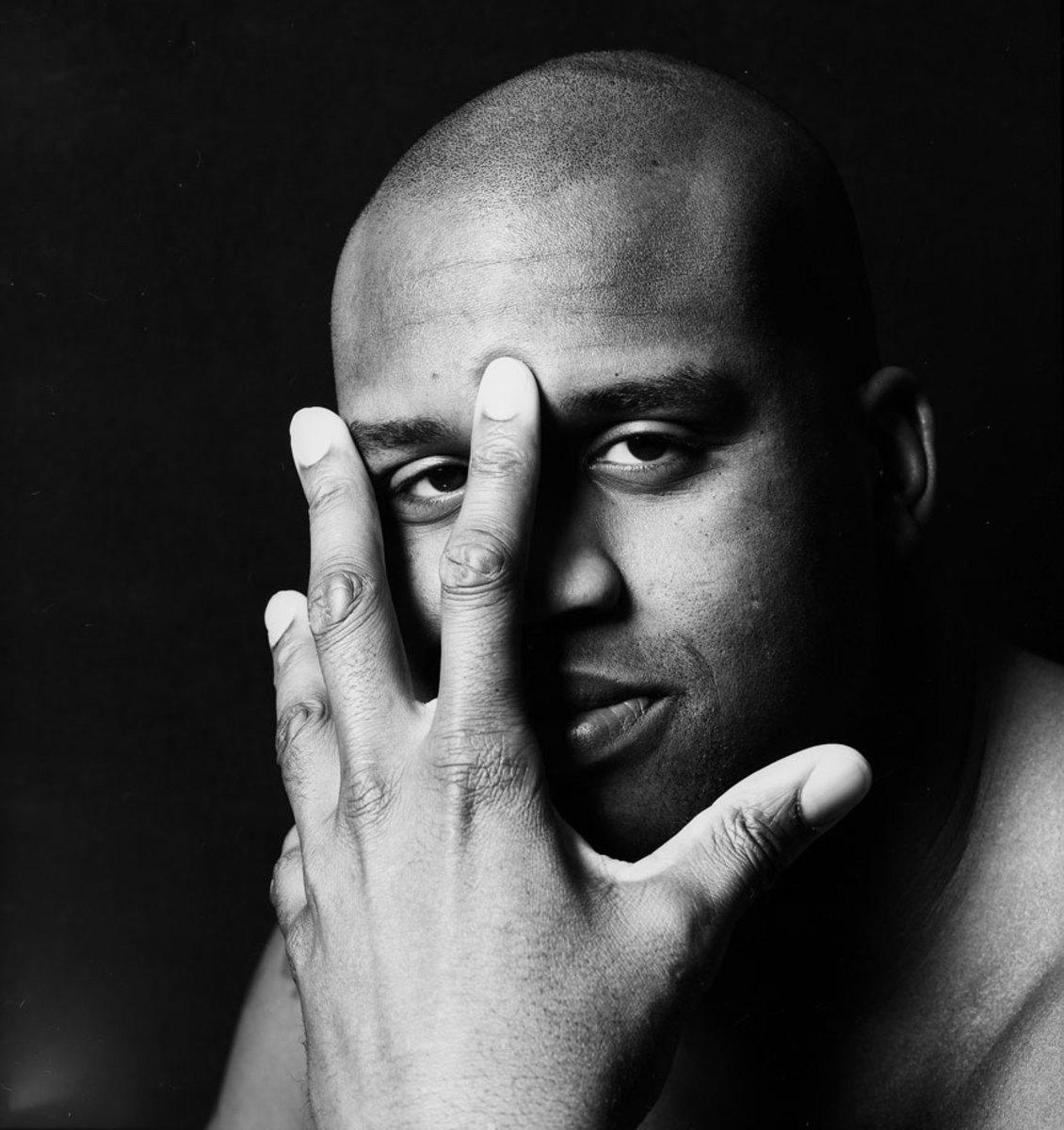

Shaquille O'Neal

2001

Shaquille O'Neal

2002

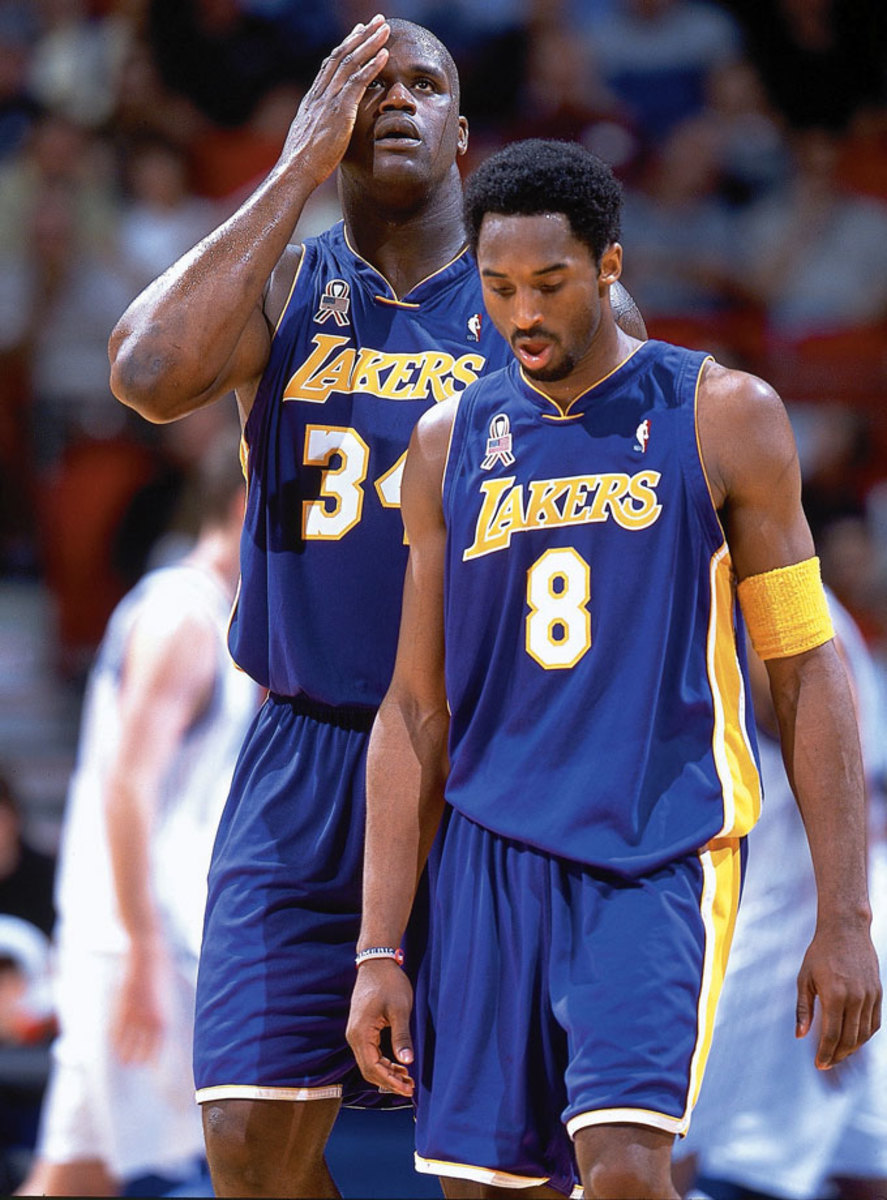

Shaquille O'Neal and Kobe Bryant

2002

Shaquille O'Neal

2002

Shaquille O'Neal

2002

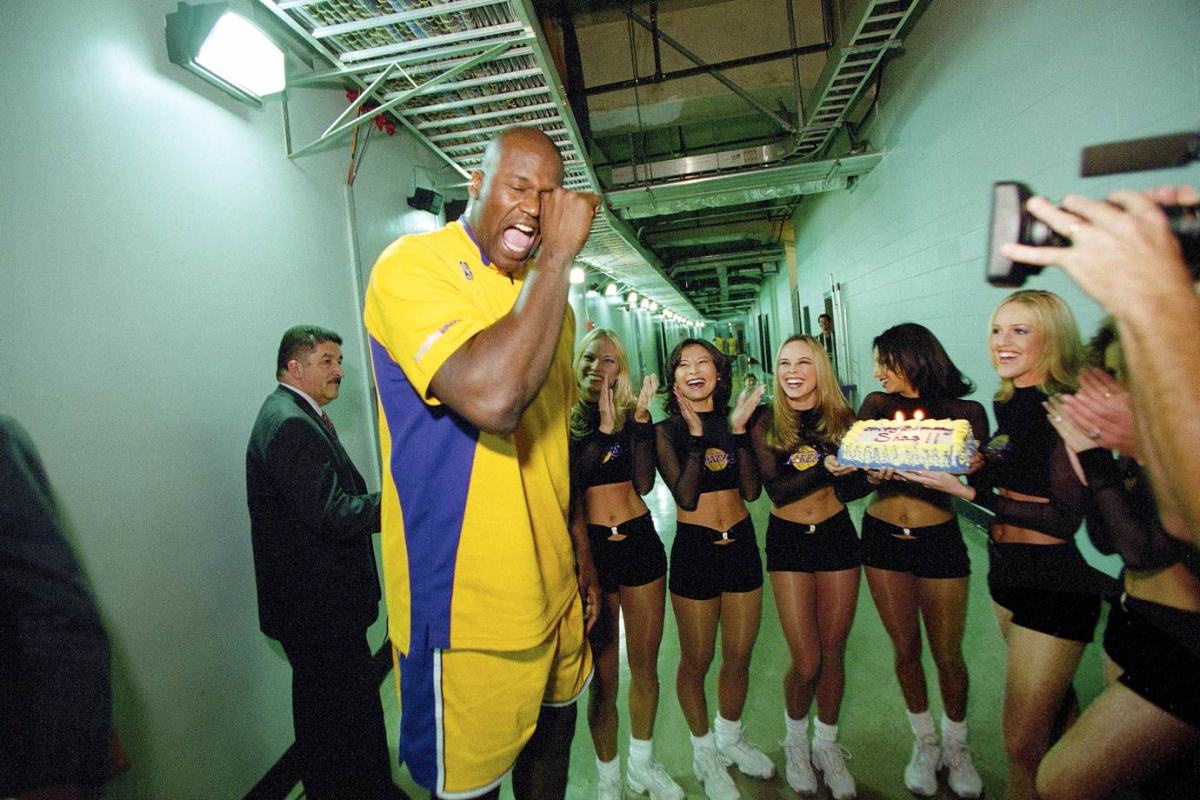

Shaquille O'Neal and the Laker Girls

2002

Shaquille O'Neal with Lakers trainer

2002

Shaquille O'Neal

2002

Shaquille O'Neal and Kobe Bryant

2002

Shaquille O'Neal and Phil Jackson

2002 NBA Finals - Game 3

Shaquille O'Neal, Jason Collins, Jason Kidd and Richard Jefferson

2002 NBA Finals - Game 3

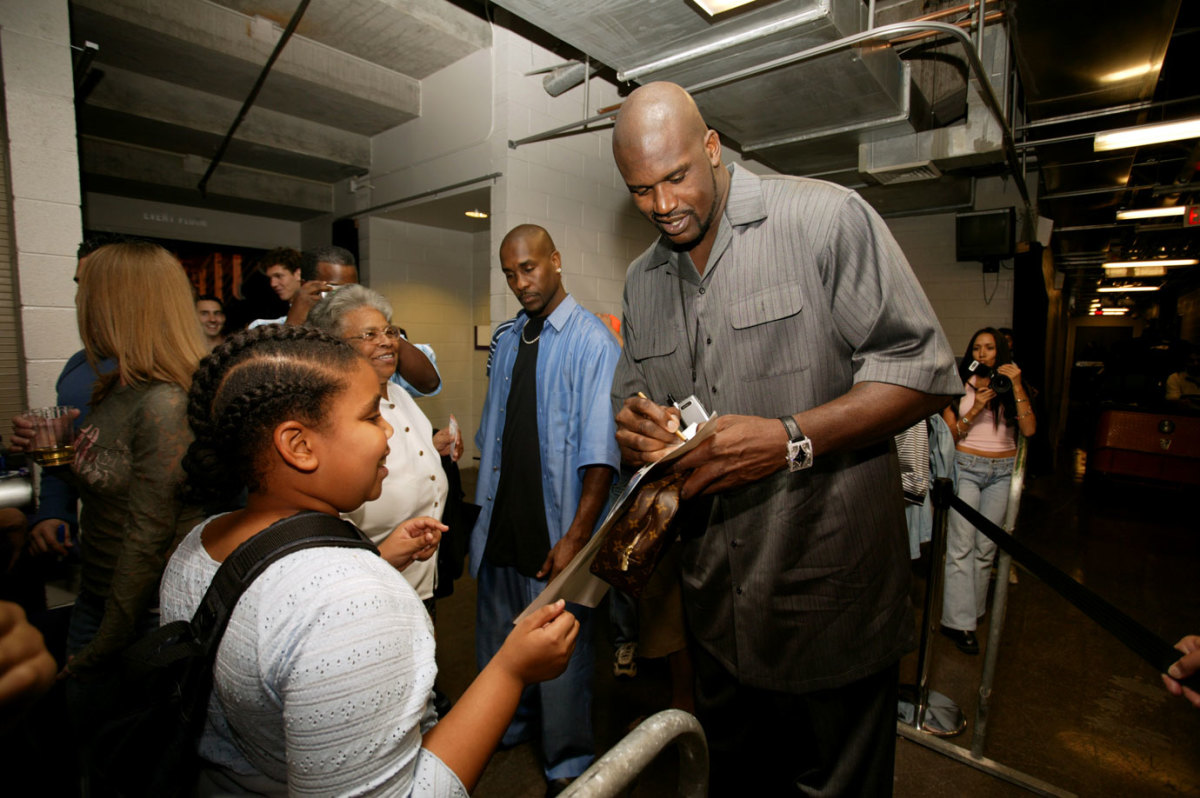

Shaquille O'Neal

2003

Shaquille O'Neal and Yao Ming

2003

Shaquille O'Neal and Earl Boykins

2003

Shaquille O'Neal, Dwyane Wade and Tyson Chandler

2006 NBA Eastern Conference Quarterfinals - Game 1

Shaquille O'Neal

2006 NBA Finals - Game 3

Shaquille O'Neal

2008

Shaquille O'Neal, Steve Nash and Grant Hill

2006 NBA Western Conference Quarterfinals - Game 1

Shaquille O'Neal, LeBron James and Kobe Bryant

2009

Shaquille O'Neal

2010

Shaquille O'Neal, Glen Davis and Manu Ginobili

2011

Shaquille O'Neal

2012 LSU vs. Washington

Shaquille O'Neal

2014 Wimbledon - Day 1

BG: Drummond missed nearly 400 free throws last season, he couldn’t stay on the court during the playoffs, and Van Gundy said that “everything is on the table” this summer when it comes to tweaking his approach, including going to the underhanded shot. Should Drummond be the poster child for this?

MG: Yeah. For this shot to come back into vogue it’s going to require someone relatively brave to be the pioneer. If someone like Drummond were to say, ‘I’ll be that guy’ and to be willing to experiment, he has very little to lose through experimentation. It’s really hard to imagine that he would be a worse foul shooter if he tried shooting underhanded. You can’t really get worse than him.

Anecdotally at least, we know underhanded is a forgiving shot. There’s more tolerance to variation than traditional free throw shooting. It makes sense for him to experiment. Why doesn’t he fly to Colorado Springs and hang out with Rick Barry for a month and see how good he gets? The worst that can happen is that he spent a month and it doesn’t work. I don’t understand why people won’t take that initial step.

BG: How long would it take for Drummond to show serious improvement? Is this really a matter of a month well spent?

MG: Barry is my only source for this. He thinks you can get pretty good quite quickly. That’s the attraction of this way of shooting. [Barry] talked about examples from when he was playing, how guys could quickly get to the 65% or 70% level. Getting up to the 90% level like he did with his shot is going to require some work.

BG: How can observers—Pistons executives, fans, media members—help Drummond lower his threshold and get over this mental hurdle?

MG: The way to do it is to get other players on the team to try it. I don’t know how many poor foul shooters there are on the Pistons, but imagine if you were the coach of the Pistons and you gave the players the choice: if you’re not shooting 75% from the line the conventional way, you’re going to have to try our experiment shooting a different way during the off-season and preseason. If you gave [Drummond] company, it becomes a lot easier. It could be kind of a fun thing, too!

It would be even easier on a team that wasn’t going anywhere. That [Pistons] team has some potential to be in the playoffs, right? If you had a team that was clearly going to be a cellar-dweller, you’d have more freedom to experiment. I think you’ve got to get a critical mass of players who try it. That would diminish the scrutiny that someone like Drummond felt he was under.

BG: Should player agents or team executives be stressing economic arguments too?

MG: If Andre Drummond or DeAndre Jordan is a 90% foul shooter, how does that change his market value? You could probably put a number on how much he adds to himself as a player. It’s not trivial. It’s not going to double the amount of money he makes. It’s going to be an appreciable amount. It changes the way he’s defended and leads to other changes to his game that we can’t imagine. The value to himself, the desirability around the league, I think it makes everyone more tolerant of the experiment.

BG: That’s tricky because Jordan is already a max salary player and Drummond will be one once free agency opens, despite their poor foul shooting. Playing the money card probably involves focusing on the big picture with endorsements and the additional opportunities that come with winning, right?

MG: The economic argument is also about your longevity as a player. Those guys are max players now, but are their careers extended? The other, much more powerful argument is: Do you want to be remembered as a great player? Do you want to help your team? Do you want to help your team make a big step? That should be a sufficiently powerful argument for someone to try something new.

• Way too early ranking of 2017 NBA draft prospects

BG: The never-ending debate over intentional fouling has the potential to radically change the value of these players, too. If the NBA adopts rules changes in pursuit of a smoother and faster game, life gets a lot easier for Drummond and company.

On the other hand, traditionalists argue that the NBA shouldn’t change the rules simply to cover up the flaw of a small group. Should the NBA alter its rules or should the players be forced to change?

MG: I want [the players] to change! I don’t think the answer is to concede that big guys can never shoot foul shots. That’s crazy. Rick Barry thinks that’s an abomination. I think that’s right. These guys have got to learn how to shoot foul shots. We can’t let them off the hook.

What if there were soccer-style substitutions in the last two minutes? Where, once you take a guy out you can’t put him back in. You put on the onus on the team with the bad foul shooters, they can’t sub them in and out. They have to make a choice. Am I going to go all the way to the end with these guys or are you going to decide you can’t afford to play them?

If you’re Andre Drummond or Dwight Howard and you knew you were never going to play in the last two minutes of a close game, you have incentive to become a better foul shooter. I like the idea that once you come out, you’re out. That would certainly speed up the game.

BG: Your position on what Drummond and Jordan should do is clear, but can you relate to the dilemma they’re facing?

MG: I’m pretty high threshold. I very carefully, right from the beginning, chose to associate with people whose values and behavior aligns with my own. I don’t think of myself as a great risk-taker. Part of what fascinates with me about Barry is how unusual and different he is from my own psychology. I think I’ve taken a pretty tame path in life.

BG: Is Barry’s single-mindedness a trait that you always value when you’re assessing athletes?

MG: Absolutely. There’s two ideas that I think are linked: What social price are you willing to pay to get better and how willing are you to evolve as an athlete as your skills change? Foul shooting touches on both those things.

The thing that defines so many great athletes in so many different sports is that as they age they changed their games. [Michael] Jordan is a profoundly different player at the end of his career than at the beginning. That’s what separates him from tons of people who were as explosive as Jordan at the beginning who never made the transition and they had lost their star status by their late-20s.

Second, how willing are you to accept as a max guy in his mid-20s that he’s reached the pinnacle of NBA-dom? How willing are you to be self-critical, to get even better? That’s really hard to do. When you’ve already achieved this thing that 99.99% of basketball players never achieve. To say, ‘I can continue to improve as a player.’ An incredibly small number of players are willing to take that second mid-career step.

LeBron [James] was clearly holding himself back during the regular season and that takes a lot of discipline if you’re as competitive as he is. To understand that you’re playing for a title contender, that you’re in your 30s, that you couldn’t play the same way you played in game 30 or 40 at this age. You’ve got to show some restraint. That’s hard, too. A lot of people find that lesson to be difficult. LeBron is a good example of someone whose intelligence has shone through in his play as he’s gotten older.

• The absolute worst free-throw shooters in NBA history

The Worst Free-Throw Shooters in NBA History

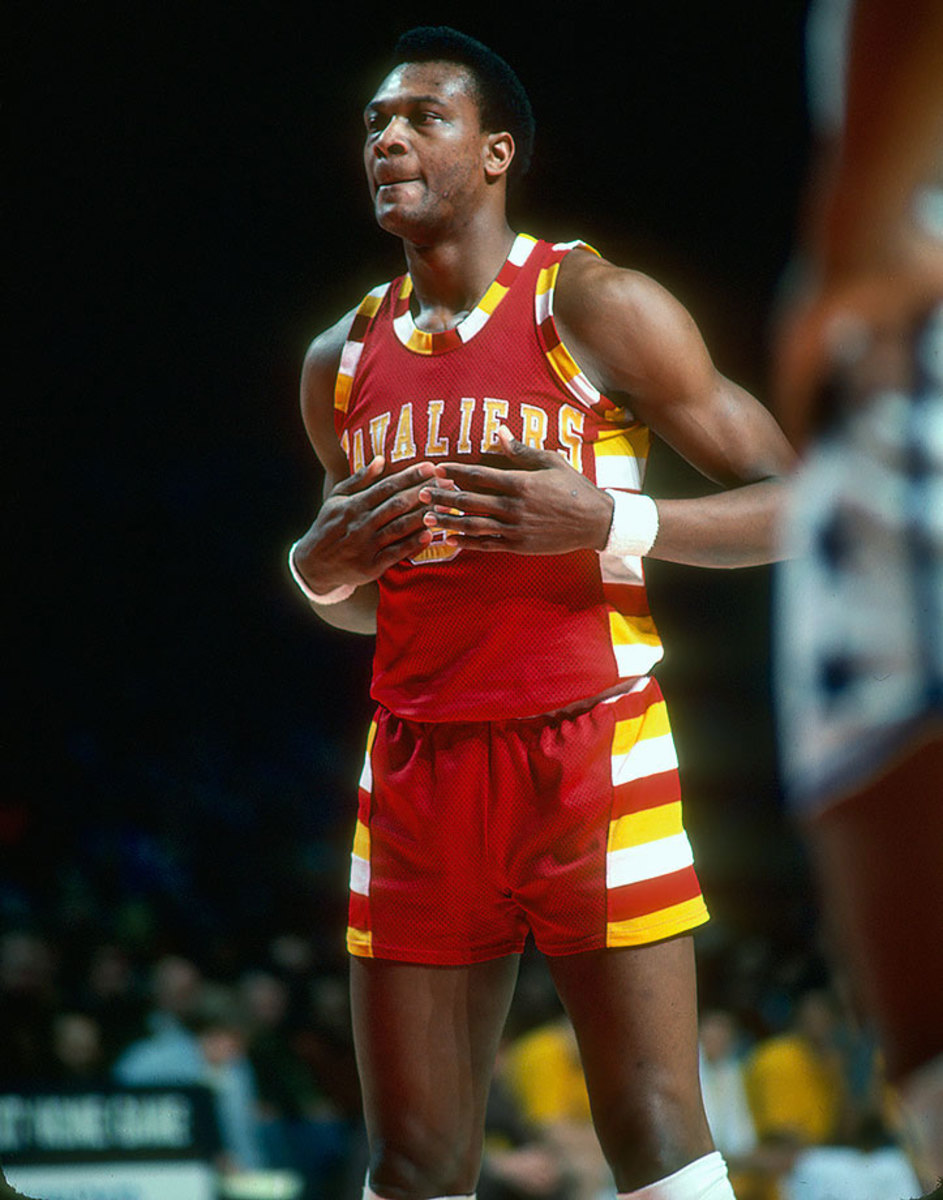

#15: Emeka Okafor — 58.4%

#14: Elmore Smith — 57.9%

#13: Kwame Brown — 57%

#12: Dwight Howard — 56.8%

#11: Dale Davis — 56.2%

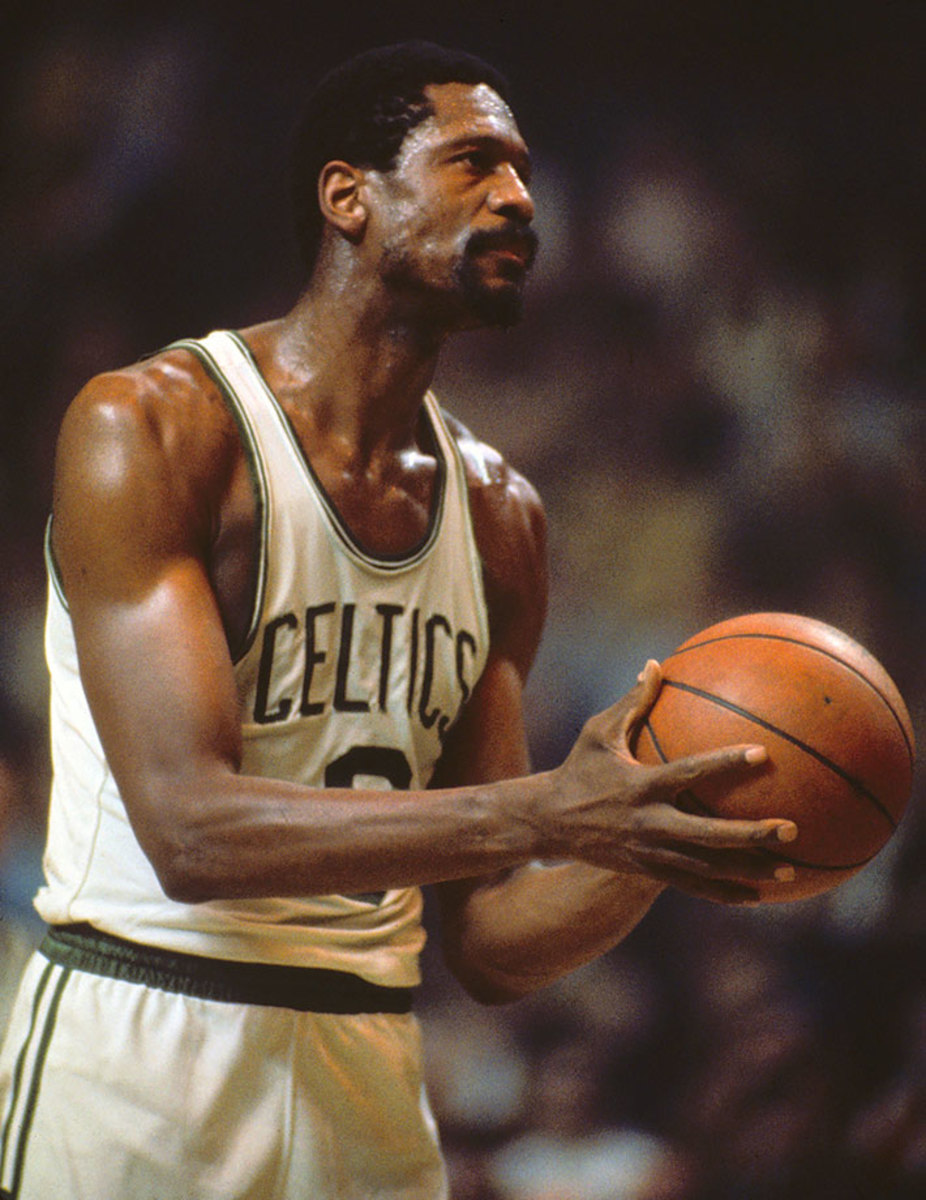

#10: Bill Russell — 56.1%

#9: Greg “Cadillac” Anderson — 55.7%

#8: Shaquille O’Neal — 52.7%

#7: Bo Outlaw — 52.1%

#6: Wilt Chamberlain — 51.1 %

#5: Andris Biedrins — 50%

#4: Chris Dudley — 45.8%

#3: DeAndre Jordan — 42.1%

#2: Ben Wallace — 41.4%

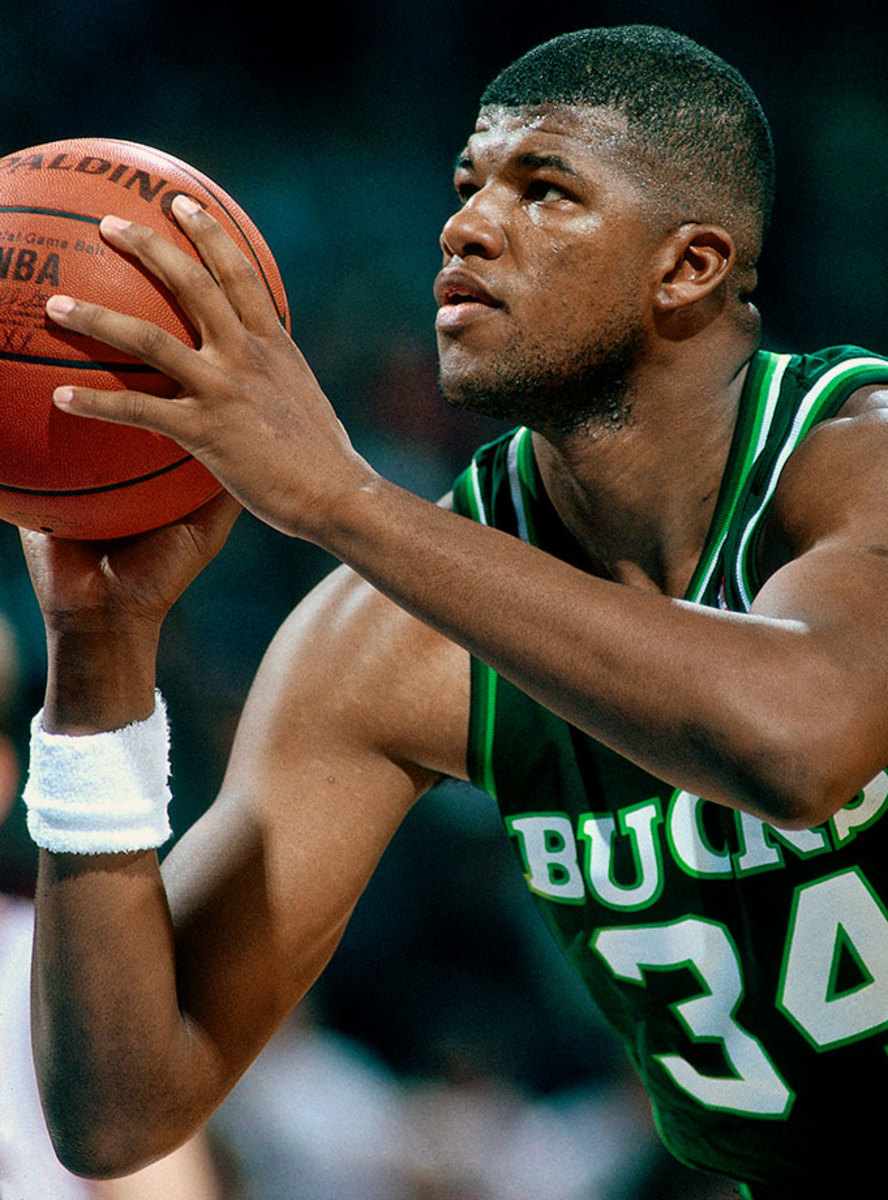

#1: Andre Drummond — 38.0%

BG: If you were NBA commissioner, what would you change about the league and what would be your guiding principles as you weighed changes?

MG: Whenever you’re thinking about making changes to a spectator sport, you have to have a clear hierarchy. Fans enjoyment is the number one consideration. Number two is the game, number three is the player, number four is the owner. Once you have that in mind, it’s easier to decide yes or no on these things. Does this make it better to watch as a fan? If the answer is yes, you do it, regardless of the other consequences on the other three.

I watched an awful lot of basketball this last playoffs and there are certain games that are unwatchable in the last five minutes. There was one Raptors game that went into overtime. The last 45 minutes of that game was the most excruciatingly boring game of my life: foul, timeout, foul, timeout, commercial, replay.

The NBA has got to do something about the fact that at the moment the game is supposed to be the most exciting is often the least exciting. It makes no sense. You’re sitting on the edge of your seat, the game is tied with two minutes to go, and then it’s like you’re watching a movie and as you approach the climax of the movie, they stop the movie! Who would stand for that? It’s unbelievable.

You want the refs to be invisible. Any time a whistle is blown that’s a bad outcome. To the extent that we can remove whistles—if we could cut the number of whistles in half, imagine how much better this would be to watch.

BG: Do you agree that the NBA often seems to prioritize tradition and “the game” over fan enjoyment?

MG: I once ran into David Stern randomly and I asked him that question: ‘For God’s sake, why don’t you get rid of some of the timeouts at the end of the games?’ He said, ‘I tried, but the coaches get really upset.’ This is exactly what I’m talking about: the coaches got to trump the fans. That’s totally wrong. It’s not their game. It’s our game. He was like, ‘There’s nothing I can do.’ That’s a beautiful illustration of what I’m talking about.

BG: OK, let’s run through a few popular rule changes that get brought up from time to time. Would you support a new setup in which players who commit six fouls are allowed to remain in the game but are subjected to an extra punishment? For example, the opponent might get three free throws instead of two if a player commits his seventh foul in a normal shooting foul situation.

MG: That’s a great idea. Escalating [punishment]. I love that idea. That’s so much better. It’s so much more interesting as a fan. You get to see this player play but the consequences of it, the stakes suddenly have to be factored in. Imagine Steve Kerr, you have Steph Curry on the floor with six fouls and two minutes to go in a close game. You really have to ask yourself, ‘Is he so good that he’s worth that type of potential downside?’ That’s really interesting. The last 30 seconds of a tight game, oh, my God, it would be so interesting.

• Top 50 NBA free agents | No shortage of free-agent bigs

BG: Curry’s success has raised numerous questions about the three-point line. Should it be moved back to make it more difficult for the average player and to encourage a better balance in shots? Should the NBA reward the super-long distance shots with a four-point line?

MG: [The new reliance on the three-pointer] has led to a more beautiful game of basketball, but I think it’s also, and this is a presumption not backed up with statistics, leading to more variable outcomes. I want to make sure that we know that and then decide if we want more variable outcomes.

In this last playoffs, look how lopsided these games were. There were very, very few games that came down to the wire. What I would love to know is if that’s a coincidence. I’d like to have way more data that says we’re now in an era with fewer nail-biters. And if we are and it’s due to the high variability of the three-point shot, then that distresses me. I don’t really want to watch Finals where one team wins by 20 and the next team wins by 20. If I thought that by tinkering with the three-point line I could reduce variability, I would be in favor it.

This will never happen, but imagine if you had a four-point line but only in the last five minutes. That would be super fun. And, what if we did stuff to make the last two minutes special? Football does this very brilliantly. Teams change their offense in the last two minutes and all of a sudden everything that’s annoying about football in the first three quarters gets exciting. They run a no-huddle. They throw the ball way more. That really works. I’d love to see teams fundamentally change their offense in the last two minutes to make for a more exciting ending.

BG: Would you be in favor of eliminating charge calls? Some writers have argued that the block/charge calls are the trickiest to officiate and that the act of trying to take a charge exposes players to injuries.

MG: I would love to experiment with that one. Do a preseason experiment or convince some college conference to play with that idea. I’d definitely like to experiment with it. Any time you alter offense/defense balance, there are unintended consequences. I want to be sure I know what the consequences are before I go forward on that one. I like it in theory.

BG: Would you favor the international goaltending rules which allow players to play the ball on the rim?

MG: I like the international approach. If you think about it, all the outcomes are positive. You’re encouraging people to do something that’s spectacular to watch and you’re removing another difficult, discretionary call for the refs. So yes, yes, yes.

• Conley stands in free agency as rare trustworthy guard

BG: What about a soccer-style advantage rule where open court foul calls are delayed to see whether a player scores in transition before the action is blown dead?

MG: I agree. I think that’s a hockey rule, too. The play continues and the penalty is called after play stops. I like that way better [because it improves the] flow of the game.

BG: As commissioner, would you have suspended Draymond Green for his blow to James during the Finals?

MG: That was a call that potentially throws the course of the whole series. You have that problem because you don’t have a proper arsenal of penalties. [This is] like the idea about giving extra foul shots after someone commits six fouls, that expands the arsenal of penalties. There should have been some other way to penalize Draymond or Golden State without fundamentally altering the course of the series. What if when you get a second flagrant, it’s a five-shot foul. I don’t know. It was just too draconian. It was completely out of step with the severity of the offense. I hate to think that there’s an asterisk on this series because the Warriors lost Draymond for a game.

BG: To close, what can listeners expect when ‘Revisionist History’ moves past the free-throw line? Do you have a specific target audience in mind?

MG: This a podcast about reexamining things we thought were settled. It’s an opportunity to go back and screw around with our understanding of the past. I think it’s for anyone who is remotely curious and has 45 minutes to kill on a regular basis, and for the people who read my books and are into the way I like to think about things.

The podcast changes over the course of the 10 episodes. The last couple of episodes are a lot less conventional. It gets weird in the middle. There are some episodes that are really quite angry, that are supposed to be. There are three coming up, a miniseries on education, that are angry and intended to make people mad about what I think has gone wrong with the educational system. There are some at the end that are really emotional. One episode in particular I think will make listeners cry. Legitimately, not because I’m manipulating their emotions, but because the subject matter is incredibly moving. There is a lot of weirdness to come.