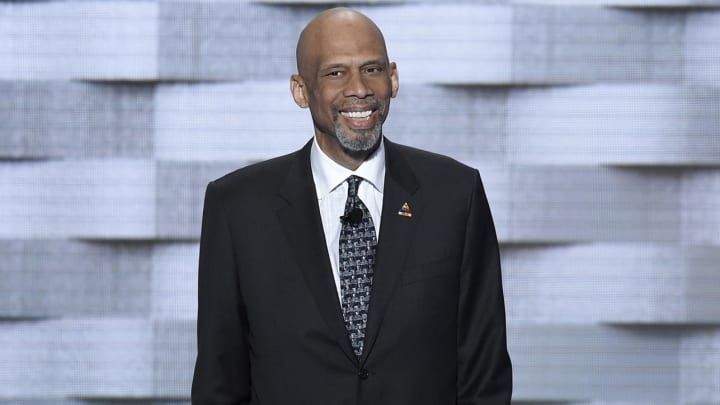

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar's DNC speech adds to a lifetime of achievements

PHILADELPHIA, PA. — He was the only speaker at the Democratic National Committee who needed a lapel microphone. This was because the podium, set for regular sized American politicians, came up to approximately hip-level. The podium was not set for people who are simultaneously basketball legends, jazz historians, noted authors, famous comic actors, cultural ambassadors, social activists, and 7'2". When he got to center stage on Thursday night, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar cracked a funny.

“Hello, everybody,” he began. “I’m Michael Jordan and I’m here with Hillary. I said that because I know that Donald Trump couldn’t tell the difference.”

He got a big laugh because his delivery was perfect, because his life always has been a life of finely jeweled movements, not cautious and careful, but thoughtful and deliberative, unfolding in the way his skyhook used to unfold. He remains one of the most fascinating Americans and the arc of his life takes in so much of the history of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. To be fair, he had a tough speaking slot. He followed Reverend William Barber, a brilliant preacher from North Carolina with a voice that seems to come from the center of the earth. And he was there to introduce a film about the life and death of Captain Humayun Khan, a Muslim-American who was killed in action in Iraq. The film, of course, was followed by a now-iconic speech in which Khan’s father, Khizir, offered Donald Trump his own pocket copy of the Constitution and declared, “You have sacrificed nothing.”

• Kareem criticizes Trump at DNC | Coaches as presidential candidates

But Kareem belonged on the stage as much as anyone did, and he did what he came to do elegantly, and without flummery or excess which, to be honest, are endemic to such events. After all, his conversion to Islam had a public impact unlike any other, with the notable exception of the conversion of Muhammad Ali, something that he accepts as a puzzling fact of American life even now, even more than 40 years after it occurred.

The transition from Lew to Kareem was not merely a change in celebrity brand name—like Sean Combs to Puff Daddy to Diddy to P. Diddy—but a transformation of heart, mind and soul,” he wrote last year. “I used to be Lew Alcindor, the pale reflection of what white America expected of me. Now I’m Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the manifestation of my African history, culture and beliefs. For most people, converting from one religion to another is a private matter requiring intense scrutiny of one’s conscience. But when you’re famous, it becomes a public spectacle for one and all to debate. And when you convert to an unfamiliar or unpopular religion, it invites criticism of one’s intelligence, patriotism and sanity. I should know. Even though I became a Muslim more than 40 years ago, I’m still defending that choice.

I was introduced to Islam while I was a freshman at UCLA. Although I had already achieved a certain degree of national fame as a basketball player, I tried hard to keep my personal life private. Celebrity made me nervous and uncomfortable. I was still young, so I couldn’t really articulate why I felt so shy of the spotlight. Over the next few years, I started to understand it better.

Part of my restraint was the feeling that the person the public was celebrating wasn’t the real me. Not only did I have the usual teenage angst of becoming a man, but I was also playing for one of the best college basketball teams in the country and trying to maintain my studies. Add to that the weight of being black in America in 1966 and ’67, when James Meredith was ambushed while marching through Mississippi, the Black Panther Party was founded, Thurgood Marshall was appointed as the first African-American Supreme Court Justice and a race riot in Detroit left 43 dead, 1,189 injured and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed. I came to realize that the Lew Alcindor everyone was cheering wasn’t really the person they imagined.

That is the place from which he always has operated. A mind at work, turning over options like worry beads, seeking out every angle, and eventually coming to a conclusion reached by an infallible compass of an individual mind. So, when he got up and spoke on Thursday night on the subject of how Humayan Khan was an American hero, he did so from a place in the country’s intellectual life that he had richly earned.

• A different drummer: Getting inside the mind of Kareem

"Donald Trump's idea to register Muslims and prevent them from entering our country," as well as "today's so-called religious freedom acts…At its core, discrimination is a result of fear. Those who think Americans scare easily, enough to abandon our country's ideals in exchange for a false sense of security underestimate our resolve. To them, we say only this: Not here, not ever."

That was his moment at the convention. With a smile and a wave, he was gone, off again to the unique life he has carved out for himself. He is a renaissance man for sure, it’s just that his renaissance is his alone, and it’s nowhere near finished yet.

He is a child of the great Harlem Renaissance, his father a jazz trumpeter. He was one of the very first basketball prodigies who became famous before he got to college. He began John Wooden’s greatest period as the coach at UCLA, winning three NCAA championships with such preposterous ease that he is the greatest college player by a margin that’s almost not worth discussing.

At the same time, in 1968, he participated publicly in Dr. Harry Edwards’s Olympic Project For Human Rights, refusing to play for the United States at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. He was 20 at the time and, later, in a piece for the Los Angeles Times , he reminisced about the minefield that was the life of a young African American celebrity athlete in those days.

At that time sociology professor Dr. Harry Edwards, only in his mid-20s, urged black athletes to boycott the Olympic Games in Mexico City. "For years we have participated in the Olympic Games, carrying the United States on our backs with our victories, and race relations are now worse than ever," he told the New York Times Magazine in 1968. "We're not trying to lose the Olympics for the Americans. What happens to them is immaterial. . . . But it's time for the black people to stand up as men and women and refuse to be utilized as performing animals for a little extra dog food." Harsh words to many white sports fans and self-proclaimed patriots alike, but for African American athletes, there was a clear ring of truth behind the rhetoric. Clearly the Olympic Games and the Vietnam War were parallel competitions. In each, blacks were supposed to go overseas to drive themselves as hard as they could in order to bring glory to their country, only to return home and still be treated as second-class citizens. All that gave me a lot to think about. Then baseball-pro-turned-broadcaster Joe Garagiola interviewed me on the "Today Show" and for the first time I spoke publicly about my concerns and frustrations regarding the direction the country was taking politically. Garagiola was clearly annoyed that I would even consider boycotting the Olympics. My response was that for black Americans life in this country was still something that included racially based discrimination in every area of life.

• Kareem Abdul-Jabbar now comfortable as ever as a public intellectual

There was no formal boycott, but everyone knew why he wasn’t there, even as he talked about the good job back in New York that helped finance his education. He allowed his actions to speak for him. Even then, he showed a fascinating, interesting mind at work, a discursive and thoughtful approach to things that was rare in those (quite literally, on several sad occasions) shoot-first times. In his professional career, he was lordly and powerful, but remained introspective and, at times, aloof. It is said that this has cost him the coaching career he might have had. But, since retirement, he has seen life open up to him. He has coached on Indian reservations. He has written books that were very well-received, including Writing On The Wall, a study of race and America that will be published in August, and, most fascinating of all, a novel centering on Mycroft Holmes, Sherlock’s brilliant, but hopelessly sedentary, older brother who is one of the more indelible of the minor characters in the Baker Street canon. And Sherlock’s description of him can be applied to Kareem just as readily:

He has the tidiest and most orderly brain, with the greatest capacity for storing facts, of any man living. The same great powers which I have turned to the detection of crime he has used for this particular business. The conclusions of every department are passed to him, and he is the central exchange, the clearinghouse, which makes out the balance. All other men are specialists, but his specialism is omniscience.

The great danger in celebrity lies in the way it accelerates a life, often to a point where the individual cannot control it. Kareem has been wary of that ever since he became a celebrity, which happened in his early teens. He has fended it off by developing and maintaining an orderly and endlessly questing mind. He has thought it all through—basketball, fame, religion, his place in the world and the world’s place in him. Not everyone that came to the podium during the convention could say that of themselves. The day before he addressed the convention, he spoke at an event honoring Congressman John Lewis of Georgia, dedicated to celebrating the civil rights plank that was added to the Democratic platform in 1948, the last time the party gathered in Philadelphia. He spoke of the importance of education, which he called “the great equalizer.” He belonged at that gathering as much as he belonged on the stage. He belongs to the world, but only on his own terms. That is what he has won for himself.