The NBA's Superteam Era: For Better Or Worse?

In the second half of the second game of the Western Conference finals, Jerry West sat in the basketball ops suite at Oracle Arena, plotting his escape. It was a familiar impulse. As general manager of the Lakers, West was famous for fleeing the Forum and driving aimlessly around Inglewood, often finding a movie theater where he could hide from televisions and radios broadcasting the games. That was back in the 1980s, when the Showtime Lakers rarely lost but West was still too nervous to watch or listen. Now he works for the Warriors, advising their owners. He is immensely proud of his new team, four megastars lighting up one hoop constellation, and he raves about Kevin Durant in the same tones once reserved for Kobe Bryant. But the reason he wanted to bail on Game 2 against the Spurs is not that he was uptight. It's that he was unenthused.

"I don't like parity," West says. "I don't like the word parity. Parity is average, and I like to see excellence. But I also like competition. I read the newspaper cover to cover every morning, and even though I don't bet, I look at the lines in Las Vegas. We were underdogs in one game this year. We were favored in Game 2 of the conference finals by 15 points. That is insane. It's not what anybody wants to see. At the end of the third quarter [when the Warriors led 106–75], I almost felt bad for San Antonio, but I also felt bad for our fans. Because if you're a real fan at a playoff game, you want to see a hard-fought battle, back and forth, and at the end somebody wins by a point and you go home worn out. You're charged. You're edgy. But we're up by 30-something, and I'm thinking, 'Hmm, I'd like to leave here if I could.' It's the weirdest thing. I've never felt that way before."

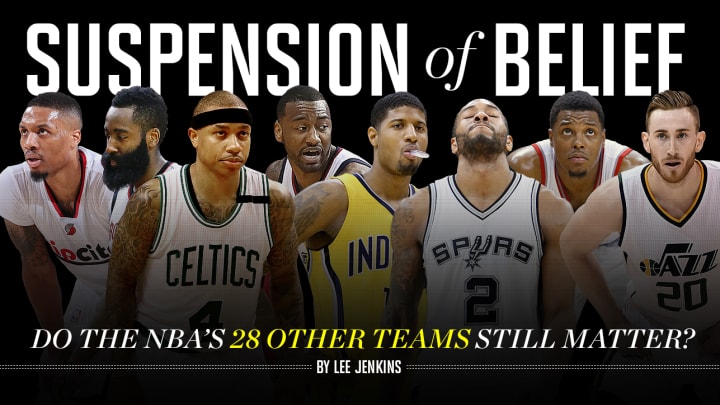

The Warriors are the first team ever to start the postseason 12–0. Their point differential, +16.3, is the largest in playoff history. During the conference semifinals against the Jazz they won four games by double digits and never trailed in three of them, wire-to-wire demolition derbies. It doesn't matter that coach Steve Kerr has been out since the first round because of complications from back surgery, that sniper Klay Thompson has struggled with his stroke or that Durant has dealt with two separate injuries. "They won 13 games in a row this season without Durant," says a franchise president. "They're the varsity, and the rest of us look like the jayvee."

One player, upon elimination by Golden State, staggered mournfully into his exit meeting with team brass. "Make no mistake," his bosses consoled him, "they'll just do the same thing to whoever they face next."

For the third straight year, the Warriors and the Cavaliers meet in the Finals, a running feud that recalls Lakers-Celtics and the NBA's coming of age. "That's what everybody is going to say, and I understand why, but I'm not sure I agree with it," counters former Los Angeles forward James Worthy, an analyst for Spectrum SportsNet. "The Lakers and the Celtics got there a lot, but I don't remember it ever being a cakewalk like this, for us or for them. You looked forward to Lakers-Celtics, but you better watch out for Mark Aguirre and Rolando Blackman, for Karl Malone and Dominique Wilkins and Bernard King. There were plenty of times, two minutes left in the fourth quarter, you didn't know. This is different. You absolutely know. These guys are going to overpower everybody."

The 2016–17 regular season was wildly entertaining but ultimately insignificant, spectacular solo acts distracting from a dearth of suspense. The playoffs were predictable, the stacked and rested laying waste to the spent and inferior. The Cavaliers punted the No. 1 seed in the Eastern Conference, lost 31 games and dropped four straight heading to the postseason. Then they located that proverbial light switch in the basement of Quicken Loans Arena and reeled off the next 10, culminating with a 44-point disembowelment of Boston, the Celtics' most lopsided home playoff loss ever. By virtue of their busy brooms, the Warriors and the Cavs—who each caught a break they didn't need when their opponents' best players, Kawhi Leonard of the Spurs and Isaiah Thomas of the Celtics, were injured in the conference finals—enjoyed a combined 43 days off between series. That gave Draymond Green and Richard Jefferson plenty of time to appear on podcasts and critique each other's steamrolled foes, which sounded like debates over Charmin vs. Cottonelle: soft or very soft.

"If I'm being totally honest, for most of us right now, the goal is just to get in the bracket where you don't have to play Golden State or Cleveland until the conference finals," says one general manager. "It's like the NCAA tournament selection show: 'We avoided Kentucky!' This is us. This is where we are. It's not, How do you beat them? Because we all know that realistically isn't going to happen. It's, How do you compete long enough that you can look at your fans and say, 'See how close we were!' Of course the result is the same. You still have no legitimate chance to win. But optically it's better."

The NBA has always been defined, and elevated, by its juggernauts. If it wasn't the Lakers and the Celtics, it was the Pistons and the Bulls, or the Spurs and the Heat. "We were really talented," says former Miami assistant David Fizdale, now the Grizzlies' coach. "But not like this, not all the way through the roster." When the Heat snagged the 2012 title, Mario Chalmers was their fourth-leading scorer, Norris Cole their fifth. For Golden State, it's Green and Andre Iguodala, who have three All-Star appearances and a Finals MVP award between them.

But the Cavs might be even deeper than the Dubs, with eight rotation players shooting higher than 40% from three-point range in the postseason, providing ample space for LeBron James to drive and dissect. "Every time he's got the ball, it's one-on-one or a wide-open three," Fizdale continues. "You're in the matrix."

The defending champs annihilated the East. James, 32, is at the peak of his powers. General manager David Griffin has assembled what Fizdale calls "a video game of a team," and owner Dan Gilbert has picked up the $127 million tab. But when West opens his sports page this week, the Warriors will be the overwhelming Finals favorites, which tells you something about the gulf between Golden State, Cleveland and everybody else. "Competitive balance," Derek Fisher says. "I remember that term."

The Thrillogy: The NBA's Superteam Showdown

Fisher was president of the players' association during the 2011 lockout, which ended in the middle of the night at a Manhattan law firm after five months of collectively bargained bloodshed. "How exactly will this look in five years?" Adam Silver, then David Stern's deputy commissioner, said the following day. "It's my hope that we'll have more competitive balance than we have now. There will always be dominant players in the league, and they'll cause teams to be dominant. It's my hope they won't congregate."

The new collective bargaining agreement, which imposed increasingly punitive luxury taxes on organizations exceeding the salary cap, accomplished precisely what Silver hoped. Five different franchises captured championships in the next six years. The Heat won two trophies, but they could not afford to buttress their Big Three, and the roster splintered. The Thunder reached the Finals once, but their precocious trio fractured when James Harden commanded the same max contract as Russell Westbrook and Kevin Durant. The Lakers put together a starry conglomerate, but it crumpled on the injury-prone backs of Steve Nash and Dwight Howard. "Competitive balance was a huge theme for the league," says former NBA executive vice president Stu Jackson, now an analyst for NBA TV. "The object was to create a more level playing field, and it definitely worked."

The ultimate reward was reaped in October 2014, when Silver earned a landmark victory as a rookie commissioner, striking a colossal nine-year, $24 billion TV deal with ESPN and Turner. "There's never been a better time to be an owner of an NBA franchise," said the Wizards' Ted Leonsis, a stunning reversal from 2011, when owners practically camped outside their arenas shaking tin cans.

Despite the bonanza, some of Leonsis's peers were more guarded. "We were worried about what would happen," acknowledges Mavericks owner Mark Cuban. The salary cap was $63.1 million, and with players entitled to half of all basketball-related income, that figure was going to climb substantially when the TV deal took effect before this season. Toward the end of 2014, Silver proposed to the players' association a plan to raise the cap gradually. "That didn't mean the players would get less money or delayed money," Silver explains. "We were going to change the formula. We were going to give in aggregate to the union whatever money was not represented in the cap, and they could distribute it however they wanted."

Michele Roberts, who had just taken over as the union's executive director, was skeptical. "Everyone was cheering the cap growing because there was money coming in," Roberts says. "I found it an oddity, and the players found it an oddity, that there would be any effort to artificially deflate the cap. There was this notion [from the league] of chaos in the marketplace because of the new money and teams' not knowing what to do. It was then my limited experience—and now substantial experience—that these GMs are pretty smart cookies, and they forecast how they'll be able to stack their teams well in advance."

Still, Roberts sent the proposal to two independent economic companies for evaluation. "They both came back and said they did not view the league's plan as a way to get more money into players' pockets," Roberts adds. "They concluded players would make less money signing under the artificially deflated cap, even with the shortfall check."

At All-Star weekend in February 2015, approximately 50 players met on Friday night in New York City and decided to reject Silver's so-called smoothing proposal. The union preferred that the cap grow as high as possible, as fast as possible, even if some players benefited more than others. "That's the way of the world," Roberts says. "Michael Jordan didn't make as much money as LeBron James." The cap swelled to $70 million in '15--16, and when the TV money kicked in the following year, it surged to $94.1 million, three times the record for a single-season increase. Before the spike, eight teams had cleared enough cap space to offer Durant a max contract, and only a few of those suitors had a realistic shot of luring him away from Oklahoma City: Boston, Miami and Houston. "That's a typical number," says one Western Conference GM. After the spike, 28 teams were able to land KD, including the one that had just posted the best record in NBA history.

Kevin Durant Can Finally Tip Balance Against LeBron James

"You know what's crazy?" the GM says. "We were all thrilled at first. It's like if somebody gives you a $20 bill. That's great, right? You can go into the free-agent market and bid on players you wouldn't have been able to afford otherwise. And then you realize, Wait a minute, everybody else got this $20 bill too. So while I might be able to use my $20 bill on Ian Mahinmi or Chandler Parsons or Evan f------ Turner, the best team in the league, the team that went 73–9, the team that can guarantee multiple championships, they can use their $20 bill on Kevin Durant. The spike took average teams and made them marginally better. It took one great team and made them historic."

The Warriors, shrewd and charmed, positioned themselves perfectly. They had the supreme talent, the alluring location and the congenial culture. Plus, their homegrown headliners Green, Steph Curry and Klay Thompson were under contract on relatively reasonable deals last summer, when free-agent salaries shot into orbit. As a result, Curry, Thompson and Green each make less than Allen Crabbe. "The guys in Golden State are fantastic, and they did everything right," says the franchise president. "I'm jealous! I want Kevin Durant! But no one can argue that timing didn't play a huge role in all this. If you happened to lock up your players any time before the spike, it was Brewster's Millions for you."

Cleveland had wisely extended Kevin Love, Tristan Thompson and Iman Shumpert in the 2015 off-season and Kyrie Irving the summer before. (He too makes less than Crabbe.) Though the Cavaliers' payroll remains stratospheric, it is hard to find a regrettable contract on their books, and post-spike they were able to retain J.R. Smith while adding Kyle Korver. The Cavs may not employ four Hall of Famers, but they're as loaded as ever. "Was the spike a good thing for the NBA?" asks one prominent agent. "Of course not. It's the last thing they wanted. But of course the agents and the players wanted it. We're thinking about the guy who has two years left in his career, or the guy who is hitting free agency for the last time, or the guy who is hitting it for the first time. The money came into the system and we wanted everything those guys deserved, whether or not it was helpful for the teams and the league."

The players who convened at All-Star Weekend in 2015 could not have foreseen, four months before the Warriors toasted their first title in four decades and 17 months before Durant reached free agency, the ultimate by-product of their decision. So many events would have to unfold, from Oklahoma City's blown lead in last year's Western Conference finals to Green's suspension one round later, from Iguodala's thwarted layup in Game 7 to Irving's cold-blooded three. Chris Paul, the union president, was not thinking about his ring count when he agreed to the cap spike. Nor was Paul's new VP, elected to office during the same meeting: LeBron James.

The NBA is not suffering, even if the Nets and the Suns are. The league set an attendance record for the third year in a row. Its social media imprint is the deepest of any professional league. Playoff television ratings are up 4% from last season, despite the litany of landslides, and broadcast partners do not sound nearly as anxious as team officials. "We saw a very deep, very competitive regular season that played out positively from our perspective on how fans reacted," says Burke Magnus, ESPN's executive vice president of programming and scheduling, who helped negotiate the $24 billion pact. Magnus believes Durant's move west only boosted interest in the Warriors.

Conventional wisdom holds that monoliths are good for TV, but according to Austin Karp of SportsBusiness Daily, NBA ratings on regional sports networks were actually down 14% this season. Golden State, still ranked No. 1, was off 10%. Of course ratings are not the indicator of interest they once were, as viewers tune in on other devices. But during a meeting with general managers at the draft combine in Chicago last month, Silver discussed efforts to shorten games and retain audiences. "We were all wondering the same thing," says one of the GMs in attendance. "Is this because the new generation just watches highlights? Or is it because everybody knows who's going to win?"

Silver has admitted he never wanted Durant to sign with Golden State, but there are benefits. For those who consume basketball as performance art, valuing aesthetics over intrigue, the Warriors are a Hamiltonian hit. For those who prefer high-pressure hoops, played on a tightrope with no net, they can still catch James in the Finals. "I see the pros and cons," Silver says. "I believe we should celebrate excellence and celebrate those teams having assembled championship rosters within the rules of the league, whether it includes a bit of fortuity and very skillful management.... But the system was designed so a team playing at a championship level wouldn't have the kind of cap room to sign another star player unless they gave up current assets. That's not happened."

Silver warns against premature hand-wringing over the supremacy of the Dubs and the Cavs, who own just one crown apiece. "Early days," he cautions. But GMs anticipate that the league's competitive chasm will expand before it constricts, as more teams choose to hoard assets and wait rather than target vets and contend now. "We're in the middle of assessing this exact thing," says one Eastern Conference GM. "You either start a rebuild and kill your fan base, or bang your head against the wall trying to win a round, maybe two rounds. But then what? Unless somebody gets hurt in Cleveland or Golden State, there's no changing it."

Injuries occur. Rifts form. Young stars emerge and old ones fade. But tectonic plates shift slowly in the NBA. Stan Kasten, now the president of the Dodgers, became the youngest GM in league history when he took over the Hawks in 1979 at age 27. Over the next decade Atlanta won 50 games in four straight seasons and Kasten picked up back-to-back Executive of the Year Awards. "But we were always second-best," Kasten remembers. "We went into every year trying, really trying. But the Celtics were so good, and Larry Bird was so freaking dominant. I remember there were times I thought, Until he retires, we're just never going to beat them."

The argument for inevitability always returns to the same place, the Lakers and the Celtics, Magic and Bird. "That's what made the NBA interesting to me," adds another East GM. "Greatness attracts people to the game. It did then and it does now." In time, casual fans won't remember the conference semis anyway. They'll just remember the Bay Area wrecking ball or the prince of Akron standing in its path. "When you have the Lakers dominating, or the Celtics or the Bulls, that's good for the league because you have these large, intense entertainment markets that are turned on," says sports economist Andrew Zimbalist. "And to what extent does the dominance of those teams create animus among fans in other markets? The Patriots have dominated, but they've created animus. That's probably good for the league. The Yankees were the same way. Everybody wants to knock the king off the hill.... Then again, as nice as it is to have a dominant team in a large market, you also need other teams to have a chance, and some rotation with those teams, so no market falls asleep."

Cavs-Warriors III: A Timeline Of The Trilogy

Zimbalist used to work for the NBA players' association, and if he had still been there in 2015, he'd have endorsed neither Silver's proposal nor the spike. He believes the union should have phased the windfall in over several years at 8% interest, but he recognizes why the players favored the approach they did. "I understand the idea that a spike is good because it takes the whole system along with it," he says. Once Timofey Mozgov signs for $64 million, every 7-footer with a heartbeat can rightly claim he should earn more.

The Warriors will get squeezed this summer, when they have to re-sign Curry and Durant, but Thompson is inked through 2018--19 and Green through '19–20. Owners and agents project the cap will level off by then, likely leaving the Dubs with astronomical luxury-tax bills if their core stays intact. Eventually the system should restore balance. But until then the onus falls on the other franchises to catch up. "All they want is a shot," says Stern. "Maybe commercially it's great to have juggernauts, but you can't do it at the expense of a feeling in every NBA city that if management does a good job, they'll have a competitive team." When Stern surveys the current landscape, he sees the spirit of the 2011 lockout fulfilled. "There are going to be outlying circumstances by virtue of certain salaries and cap space where teams can put together the ability to sign three or four players. But I still think it's a very competitive league."

The trouble, as the Logo sees it, is the preponderance of organizations asking 19-year-olds to narrow the divide. Someday, Markelle Fultz might capsize LeBron, and Lonzo Ball might vault Curry. But that won't be any time soon. "All these teams keep hoping they'll help themselves in the draft, but a lot of times they won't," West says. "When I look at this league, I see a lot of teams that are very average and a lot of teams that are really struggling. It goes to the age of the teams. Some of them are so young, they may play their fannies off, but they're still going to get beat. And it also goes to the talent dispersal."

Of course, West recruited Durant to Golden State last summer, 20 years after he signed Shaquille O'Neal as a free agent and acquired the rights to Bryant from Charlotte. But the Bryant trade, for Vlade Divac, was not the only move West made on draft night in 1996. With the 24th pick, he tabbed Fisher, a feisty floor general from Arkansas-Little Rock who was not as gifted as Bryant but equally driven. "When we were rookies, Kobe and I used to play full-court one-on-one all the time, and looking back, I had no shot to win," Fisher remembers. "But at no point did I think I couldn't guard him or couldn't beat him. Guys have to respect each other, but when I watch these playoff games and see them patting each other on the back and helping each other up all the time, it tells me there might be too much respect. It tells me players are believing in the superteams, believing in the foregone conclusions."

He is reminded of Raptors point guard Kyle Lowry, venting to the Vertical in the midst of the second round that "no one is closing the gap" on James. Fisher, who won five rings with the Lakers, cannot digest such a sound bite. "I don't feel sorry for the Toronto Raptors. I don't pity the Boston Celtics. The shots they missed are not a collective bargaining issue. Obviously, when you have talent, it's easier. But foregone conclusion? Impossible to beat? They're not immortal. I played with some of the biggest, baddest dudes on the block, and there were plenty of times we could have lost. You can't convince me it's already written. You just can't. Is Kevin Durant going to feel the pressure? Will he try to do too much? Those are factors you can't predict."

Perhaps Cavs coach Tyronn Lue should bring Fish to Oakland as a Game 1 guest speaker. "There used to be a time, with Magic and the Celtics, Jordan and the Pistons, you had to go through the big player, the big team, to reach your destiny," Fisher says. "We've got a lot of guys that won't go far enough beyond their perceived limits to step up and beat these teams. The guys who get the most out of themselves are the ones who win. That's what it comes down to.

"Do you believe you can do it?"

Lee Jenkins joined Sports Illustrated as a senior writer in 2007. Since 2010 his primary beat has been the NBA, and he has profiled the league's biggest stars, including LeBron James and Kevin Durant.