How the present-day Warriors rekindled a franchise legend's love of the game

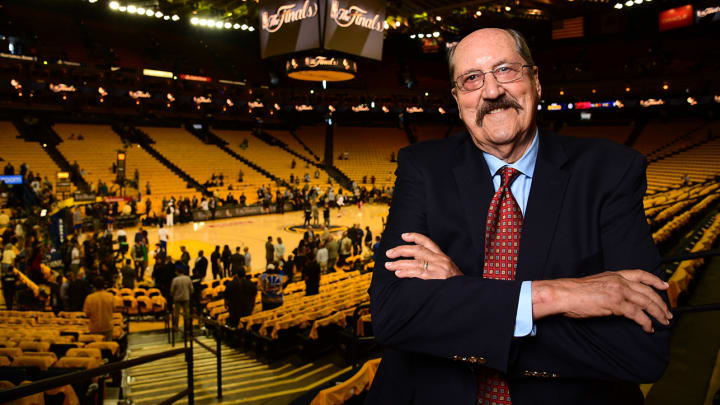

The septuagenarian at courtside, tall but a little stooped-over (“Six-foot-seven has become 6' 4",” he says), is not familiar to the majority of the fans at Oracle Arena in Oakland. He could be one of those Silicon Valley tech originals, but, in old-school jeans and pullover sweater, he doesn’t give off that go-go, multimillionaire vibe. So why are so many notables stopping by to say hello, like Warriors majority owners Joe Lacob and Peter Guber, advisor Jerry West, even Kevin Durant and Klay Thompson?

“Everyone is very nice to me anytime I come around,” says Tom Meschery with a small smile.

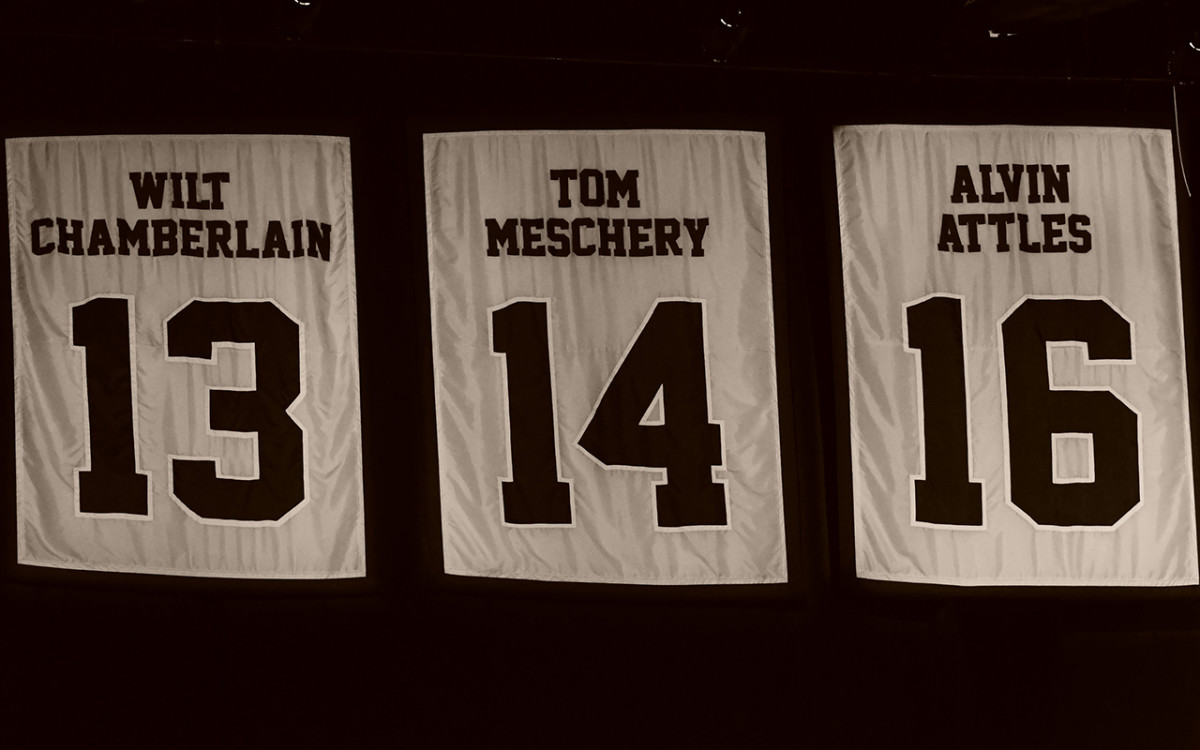

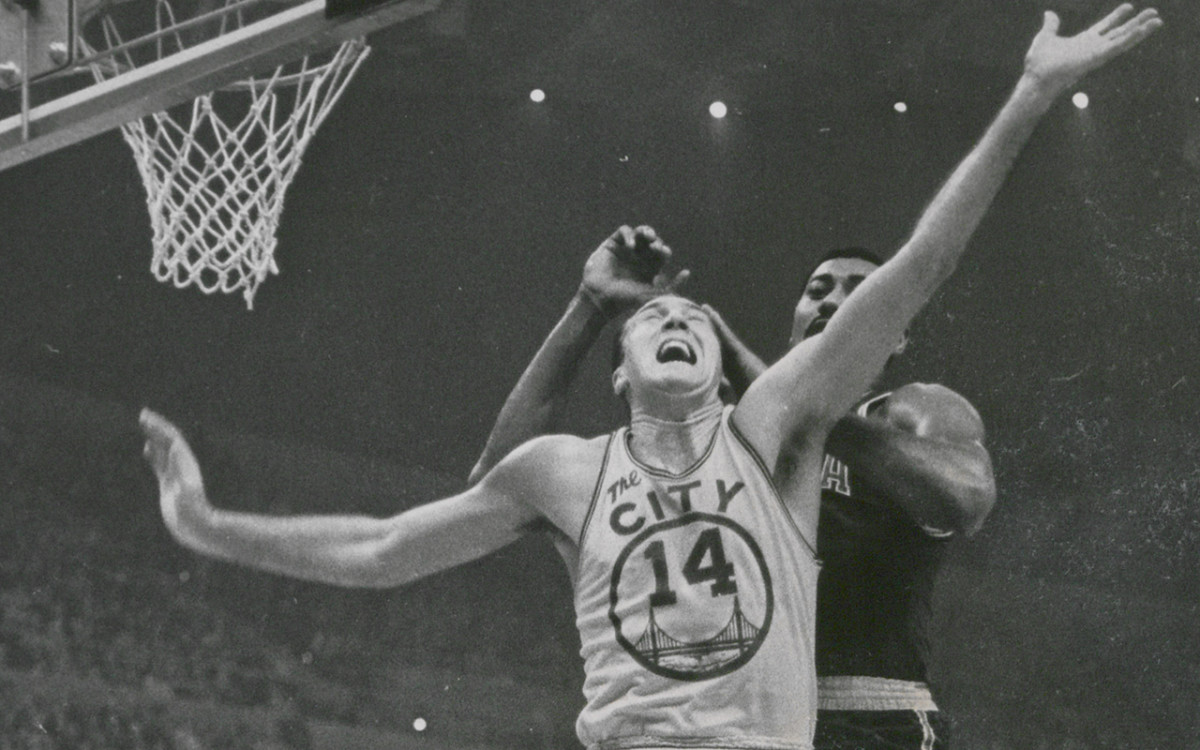

If the fans look up, they can see a tribute to Meschery. His jersey, 14, is there alongside Wilt Chamberlain’s 13, Al Attles’s 16, Chris Mullin’s 17, Rick Barry’s 24 and Nate Thurmond’s 42. Meschery is at the team’s practice facility, too, on the wall, drawn in silhouette, right between Manute Bol and Purvis Short, muscular and mustachioed, looking for all the world like he’s ready to rip somebody’s head off, ferocity being his best-known characteristic during a 10-year playing career.

But if you think the current Meschery, 78, looks more like a poet than a former All-Star power forward who had two double-double seasons and came close three other times while scoring nearly 10,000 career points, well, you’d be correct. He’s written four volumes of poetry—his elegy for Chamberlain, whom he played alongside on the night that Wilt scored 100 points, is wonderful reading—and is currently working on the second novel in a series called The Brovelli Boys Used Car and Detective Agency. Literary talent comes naturally because he is, after all, related on his mother’s side to—wait for it—Leo Tolstoy, “ol’ War and Peace himself,” as Meschery puts it. Family legend has it that Meschery’s great-grandmother kicked Tolstoy out of her house in St. Petersburg for being insufficiently religious.

And to a few generations of kids at Reno High, Mr. Meschery was just that wonderful oversized English and creative writing teacher, not poet, player or pugilist.

Right now Meschery is one of the most avid and knowledgeable Warriors analysts, as evidenced by his blog, “Meschery’s Musings on Sports, Literature and Life.” Watching the new version of his old team, he says, did nothing less than revitalize him.

• Warriors fans: Get your 2017 championship gear here | Order SI's commemorative package

He was born Tomislav Nicholiavich Mescheriakov in 1938, in Harbin, Manchuria, the final stop for his Russian parents, who years earlier had fled the 1917 Revolution. “The Bolsheviks shot most of my relatives,” says Meschery, whose mother, Masha, was from an aristocratic family, and whose father, Nicholas, was an officer in the White Russian Army. The most notable Mescheriakov victim was Masha’s father, who was summarily executed after being implicated in an unsuccessful plot against the head of the Russian Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky.

Years later, after Meschery had become a college basketball star and two-time All-America selection, he was invited to join an AAU team that would tour Russia. “My mother wouldn’t let me go,” says Meschery. “She was convinced I’d be recognized and thrown into jail because of the family connections. No, Russia was not the place for the Mescheriakovs. Maybe I could’ve gone back after things died down and been rich. Or maybe I could’ve gone back and been shot.”

Nicholas Mescheriakov got out of Manchuria before the start of World War II, intending to bring his family with him to San Francisco, where he had found work as a longshoreman. But their visas were delayed, and Tom, his mother and his sister, Ann, were considered “stateless” by the Japanese and put into an internment camp near Tokyo. “I have very strong memories of the camp,” Meschery says of their four-year stay. “It was quite hairy. But we made it through.”

They finally joined Nicholas in San Francisco after the war ended. But another war, the Cold War, was heating up, and the parents decided that the Mescheriakovs should become the Mescherys. And so did eight-year-old Tom learn early what it was like to be an outsider.

“When I got to San Francisco my parents spoke only Russian,” says Meschery, “but I didn’t want any part of it. I wanted to be an American, and sports was a big part of how you did that. My father thought I was crazy. He wanted me to go into the army and just couldn’t see the value of playing sports.”

'I'm Ready': The Text That Started The Warriors' Dynasty

Meschery learned English largely by watching American movies, adopting some of the tough-guy argot of Cagney and Wayne, and he learned basketball on various Bay Area playgrounds. That was the same territory where a decade earlier Hank Luisetti honed his revolutionary “one-handed jumper,” and two decades later a talented guard named Jason Kidd would begin turning heads. From time to time Meschery did blacktop battle with University of San Francisco stars Bill Russell and K.C. Jones.

Meschery was tall, tough and tempestuous, but he had a game, too, a nice midrange jump shot, a knack for passing and excellent defensive technique. He attended college at St. Mary’s in Moraga, about 20 miles east of San Francisco, “far enough that I was away from home but close enough that I could get a good Russian meal.” Meschery had a terrific career with the Gaels—his number 31 is one of only three retired numbers, along with Matthew Dellavedova’s 4 and Patty Mills’s 13—but he believes he made the pros mostly because of his play for the San Francisco–based Olympic Club in the high-caliber AAU system, which was dominant at the time.

The Philadelphia Warriors, who chose Meschery with the seventh pick of the 1961 draft, already had a center. His name was Chamberlain. In that legendary game in Hershey, Pa., when Wilt reached the century mark, Meschery played 40 minutes, scored 16 points and collected seven rebounds. “I don’t remember much about it,” he says, “other than we kept getting Wilt the ball and he kept scoring. Hell, we threw it into him from out-of-bounds. I do know this: The worst mistake I ever made in my life was not grabbing that game ball. I’d be a rich man today.”

The 100-point game is not Meschery’s most vivid memory of the 1961–62 season; that came in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference finals against Boston. The game was tied, “and the Celtics had the ball with just seconds to go,” says Meschery. It’s obvious that his brain has sifted through this scenario a thousand times. “Tom Gola says to our coach, Frank McGuire, ‘Frank, let me guard Sam Jones. I’m taller.’ We all knew Guy Rodgers couldn’t stop Sam because he couldn’t guard his grandmother. But Frank waved it off. Sure enough, they inbounded to Russell; he got it to Sam Jones, who makes a shot and we lose. And I know we would’ve won the championship because we beat the hell out of the Lakers every year.”

In the summer after Meschery’s rookie year he was serving in the Army Reserve when his sergeant awakened him with some joyful news: “I see you’re going back to San Francisco.” Says Meschery, “I had a couple of beers that night, I can tell you.”

• From Cow Palace to Capital Centre, a look back at the 1975 Warriors-Bullets Finals

Warriors owner Eddie Gottlieb had indeed moved the team to Meschery’s home, and the Mad Russian, as he (perhaps inevitably) came to be known, spent the next five seasons in the Bay Area cementing his reputation as a reliable scorer, rebounder, enforcer and collector of technical fouls. “After a while I started yelling in Russian so nobody knew what I was saying,” says Meschery. “But Mendy Rudolph once gave me a T and told me, ‘I don’t know exactly what you’re saying, but I don’t like your tone.’” Meschery had so many battles with the Lakers that L.A. immortal Elgin Baylor once remarked that a Warriors-Lakers game “didn’t begin until Tom Meschery and Rudy LaRusso got in a fight.”

Meschery also became something of a Wilt Whisperer, spending 2 1/2 of those seasons in San Francisco with Chamberlain before the big man was traded to the Philadelphia 76ers. “I loved Wilt,” says Meschery. “He was the most misunderstood guy on the planet. Sweetest, kindest, gentlest guy I’ve ever known.”

Meschery has thought long and hard about the comparisons between Wilt, who won only two titles, and Russell, who won 11, and says this: “Russell was hardnosed, persnickety. Always had a chip on his shoulder. He could be a bright and funny man, too, but there was something serious about him almost all the time.

“Russ won championships with great players, and, yes, it’s true that Wilt would’ve won more titles if he had Russell’s teammates. But no, he would not have won as many. Russell was the heart of that team, and the defense that he demanded as a player defined the Celtics. Wilt just didn’t have that kind of effect on his teammates. Wilt’s personality could rub players the wrong way. That steady stream of championships? Only Russell could’ve done that.”

In 1967, Meschery was taken by Seattle in the expansion draft. Once, exasperated during a SuperSonics game against the Sixers, he dared to challenge his old friend. “I came after Wilt, and he just held onto my head,” Meschery remembers, laughing. “I was like a cartoon character, something out of Abbott and Costello. I’d fight almost anybody, but I never did that again.”

When Chamberlain died in 1999, these were among the words Meschery wrote in “Mourning Wilt”:

This morning, I wake up thinking big:

Time to crack a dozen eggs, fry all the bacon.

I think I’ll never shave. Let my beard grow

As long as an epic . . .

Spend the afternoon with Aquinas’ five proofs

of God’s existence: the Uncaused Cause,

or was it the Divine Plan that toppled Wilt?

Let the day end as it began with a red sun,

and let there be a blonde soprano

with big bosoms belting out her last aria.

Meschery had four solid seasons in Seattle before retiring in 1971. While he was there he sat in on a class at the University of Washington taught by Mark Strand, who would become America’s poet laureate in 1990. Meschery had been writing poetry in earnest since college, plumbing that deeper part of him, “that dark Russian soul,” as he puts it. Years earlier, during his summer in the Reserve, Meschery had made contact—quite literally—with another soldier who would become a well-known American poet. “During a post pickup game I went in for a layup and this guy knocked my legs out from under me,” said Meschery. “I broke my left wrist and missed a bunch of games when I went back [to the Warriors]. It wasn’t until years later that I found out that the guy who did it was Stephen Dunn, who became one of America’s greatest poets. [Dunn, who played at Hofstra, won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for his Different Hours.] What are the odds of that? Years later we did a reading together in Sacramento and I said, ‘Stephen, you’re a fine poet and a dirty player.’”

Strand, who died in 2014, helped Meschery get into the celebrated Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where over two years Meschery earned his M.F.A. and found his poetic voice. “I had been writing bad Carl Sandburg,” says Meschery. “You know, all that ‘little cat’s feet’ stuff. It worked for Sandburg but not for me. But after Mark’s class and Iowa it all kind of pulled together.”

Still, even years after he retired from the game, Meschery couldn’t get basketball out of his life. He spent two seasons as a Trail Blazers assistant and later coached basketball in West Africa for the U.S. Information Agency. But something was missing, and coaching didn’t fill the void. He wasn’t a great X’s and O’s man, and he got angry and depressed when his players didn’t extend maximum effort, as he always had.

So Meschery decided to become a teacher. He already had his B.A. from St. Mary’s, so he got his teaching certificate from Nevada, Reno in 1981 and landed a job teaching English and creative writing at Reno High. He remained there until retiring in 2005.

“Teaching gave me energy, gave me life,” says Meschery. “It was kind of like sports in that it was a very high-intensity activity.” One of Meschery’s mentors around the San Francisco hoops scene had been Albert (Cap) Lavin, the father of former UCLA and St. John’s coach Steve Lavin. Cap had been an outstanding player at the University of San Francisco in the late 1940s but devoted his career to teaching and writing.

“In many ways I see my life as running parallel to Cap’s,” says Meschery. “I’ve been doing poetry far longer than I did basketball. I think of myself more as a teacher and writer than a former basketball player.”

Meschery’s life with his second wife, Melanie, a painter, has been a happy one. Her influence is clear: Melanie taught him drawing, and Meschery is quite possibly the only former NBA player to have made a pilgrimage to Italy in search of original Caravaggios. (He missed watching the first round of the 2017 playoffs because he and Melanie were on a “sketching trip” to Greece.) Meschery might have kept on teaching a while longer, but in ’06 he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer of the white blood cells, and roughly a year later underwent a stem-cell transplant. The disease is incurable but often has long remission times—which has been the case with Meschery.

By the time of his diagnosis, his connection to the Warriors and the NBA was all but gone. Meschery despised the team’s ownership group, which since 1995 had been headed by Chris Cohan, and he found the ’90s style of NBA play joyless and overly individualistic. But a few things happened that created a perfect storm of rediscovery.

First, after his transplant he was all but quarantined in his then-home in Truckee, about three hours northeast of San Francisco, his son bought him the NBA TV package. He began to watch and found that the game had changed for the better, become more open and free-flowing. A new Warriors ownership group headed by Lacob and Guber (legends in Silicon Valley and Hollywood, respectively) began to retool all aspects of the organization, and an old Meschery opponent, West, was brought on as a consultant. Among the new hires was president and COO Rick Welts, whom Meschery had known decades ago when Welts was a ball boy for the Sonics. “Very few players treated ball boys with respect,” says Welts, “but one who did was Tom Meschery.” Welts reached out; Meschery reached back.

Then Steph Curry got good and the Warriors got better, and then Curry got really good and the Warriors got a lot better. Meschery was hooked. “I loved Curry—who doesn’t?—and I really started identifying with Draymond Green,” says Meschery. “We were both undersized players who were asked to do so much more than a normal power forward. I had to score as well as pound the boards. Now, overall, obviously, Draymond is a lot more talented than I was and certainly a far, far better ballhandler. But I see a lot of myself in him.”

Steve Kerr's Celebration: Soaked In Champagne And Joy

Meschery was among the former Warriors that Steve Kerr brought back to meet the current players at a preseason practice in 2014, shortly after Kerr got the coaching job. Young guys may not grasp history, but they understand ceilings—they needed only look up to see the retired number to know that this unassuming old guy could play a little. There was a franchise-wide effort to link the team’s past and present, and Meschery felt that pull.

It was also around this time that Meschery began a memoir and he decided to frame it around the 2014–15 season, artfully mixing observations about his adopted team with memories from his own playing days. An excerpt:

I watch them play and I’m taken back in time

To the heat and smell of the sunbaked asphalt

of playgrounds and youthful competition that for all

of us marked the beginning of our careers, when there

was not a care in the world except the ball back-spinning

into the net and girls watching us from behind the net.

“I watch and I think that this is the way basketball was played on the playgrounds,” says Meschery. “The Warriors led the way—they pass, they screen away, they cut, it’s fluid—but the whole league was going in that direction. If it wasn’t for some of the banging, they could do without the referees, call their own outs and fouls.”

Meschery stops his reverie and smiles. “I know I’m a romantic at times. But it just seemed to me they were . . . having fun.”

Every once in a while, when Golden State’s up-tempo style turns a little too, well, imaginative, the old fundamental forward will gripe ever so slightly about their sloppiness. But it’s part and parcel of the Warriors, as Meschery sees it. He doesn’t carp about Curry’s turnovers; he’s more likely to describe Curry’s “eclectic passing.”

Meschery is just grateful that it all came around again, that he feels a part of something bigger.

“There’s lots of people in the Bay Area who look at my banner and say, ‘Who’s that guy?’” says Meschery. “I understand that. In terms of production, I’m not Rick Barry or Wilt Chamberlain or Chris Mullin.

“But I’m homegrown, a child of San Francisco. I was on the first team that came here from Philadelphia. I feel a very strong connection to the Warriors. So while I’m not the Best Warrior or the Immortal Warrior or anything like that, I like to think of myself as the First Warrior. And that makes me very, very proud.”