The after-party: Inside the life of the modern professional athlete in retirement

Technically, you’d classify it as laughter—only this was a deeper, richer and louder variant than usual. The sun had set on the outdoor seating section at Butcher Block Grill, a kosher steak house in Boca Raton, Fla. A large table of large men—who, to a striking degree, did not match the demographic of the rest of the older, whiter, Jewisher clientele—stayed into the spring night, and the conversation turned to the whereabouts of a missing invitee.

“Where’s Metta at?” asked Rod Strickland, 50, who’d driven in from his home in Tampa.

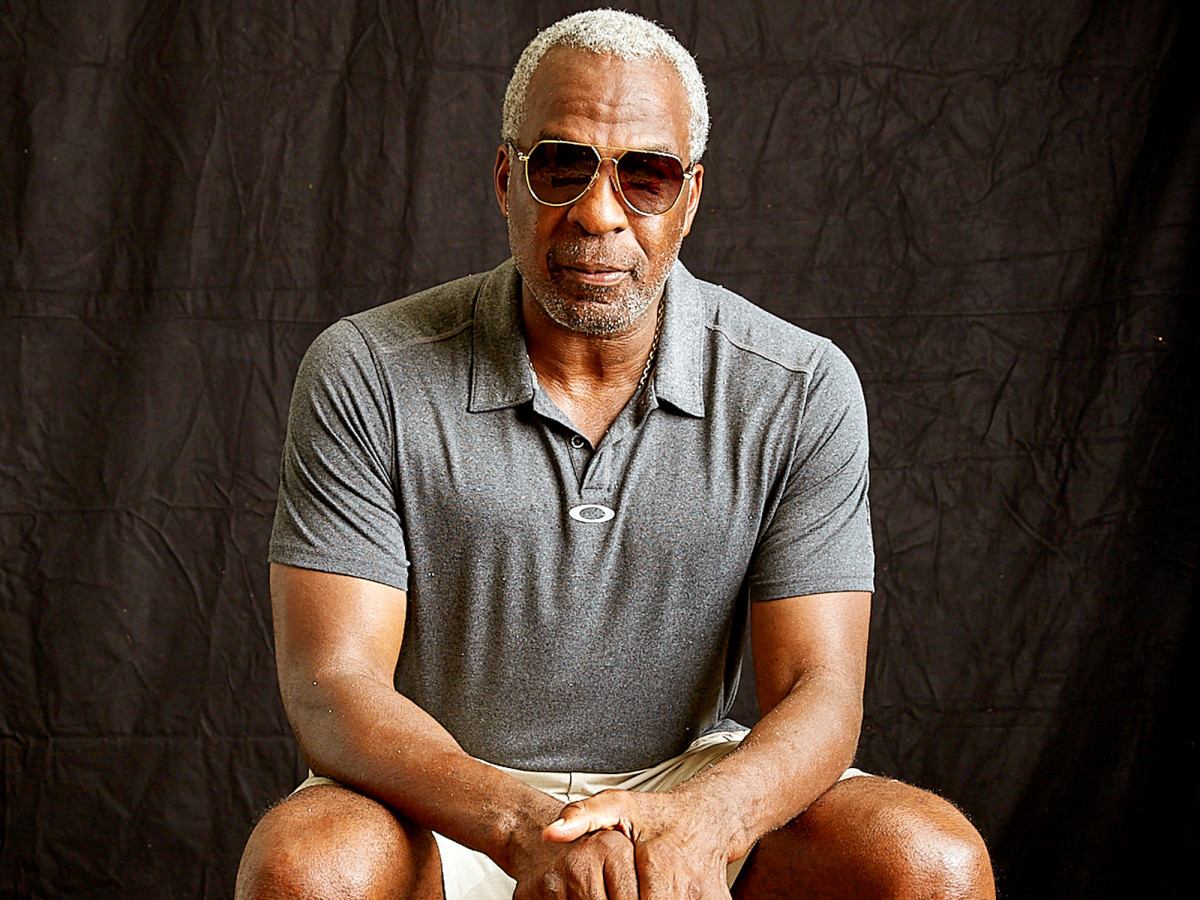

“Who?” Charles Oakley, 53, of Cleveland, asked crustily.

“Metta World Peace . . . Ron Artest,” said Strickland. “Whatever he’s calling himself.”

“Metta? He couldn’t come,” explained Jayson Williams, 49, a local. “This is for real: He said he’s meeting with Warren Buffet.”

Whether or not the absence of Peace/Artest was actually on account of his meeting with the ultrarich investment guru—no confirmation was forthcoming—it would have been in keeping with his persona. And the hearty guffaws and knee slaps that followed were in keeping with the occasion.

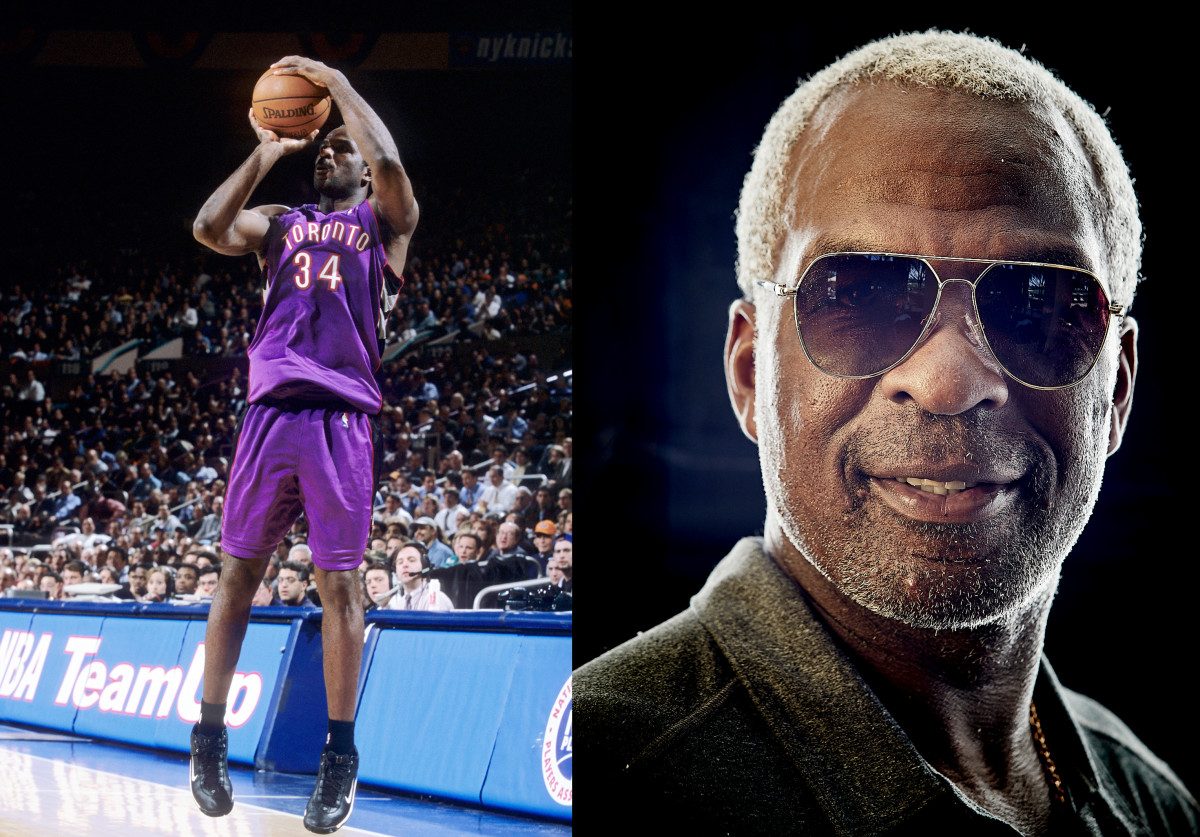

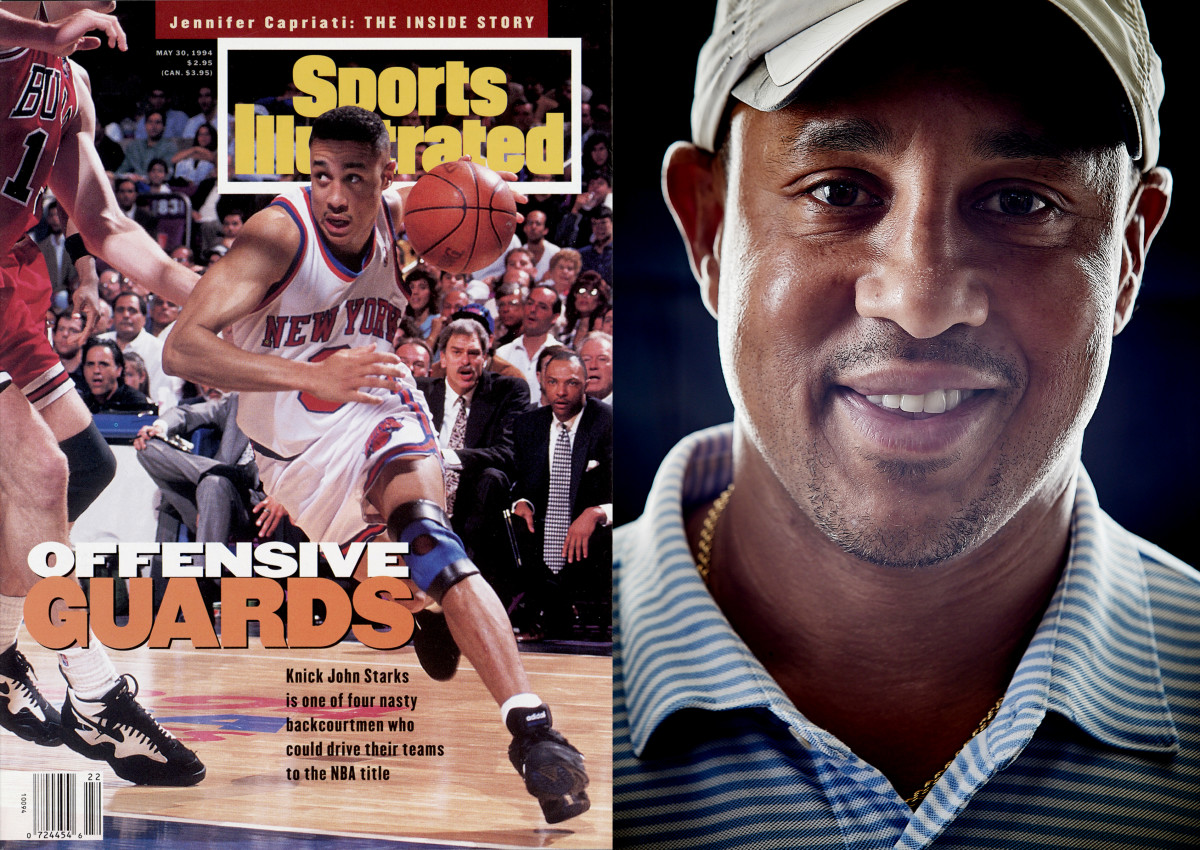

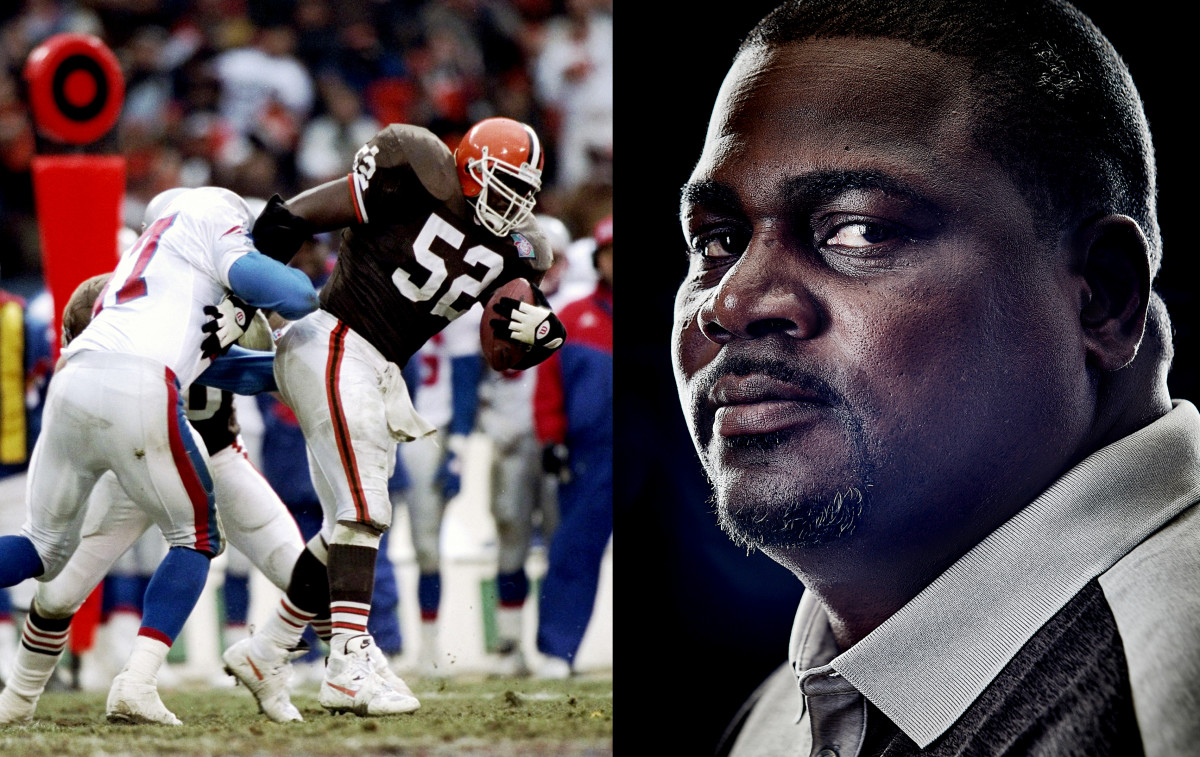

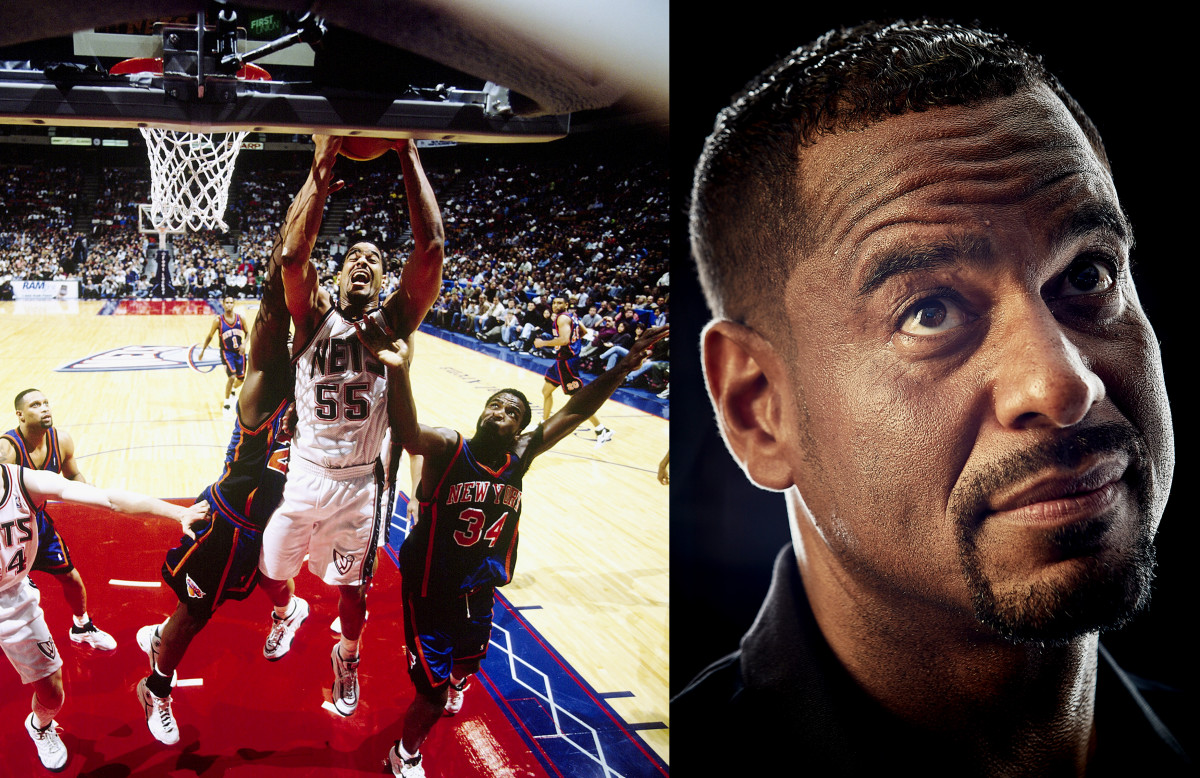

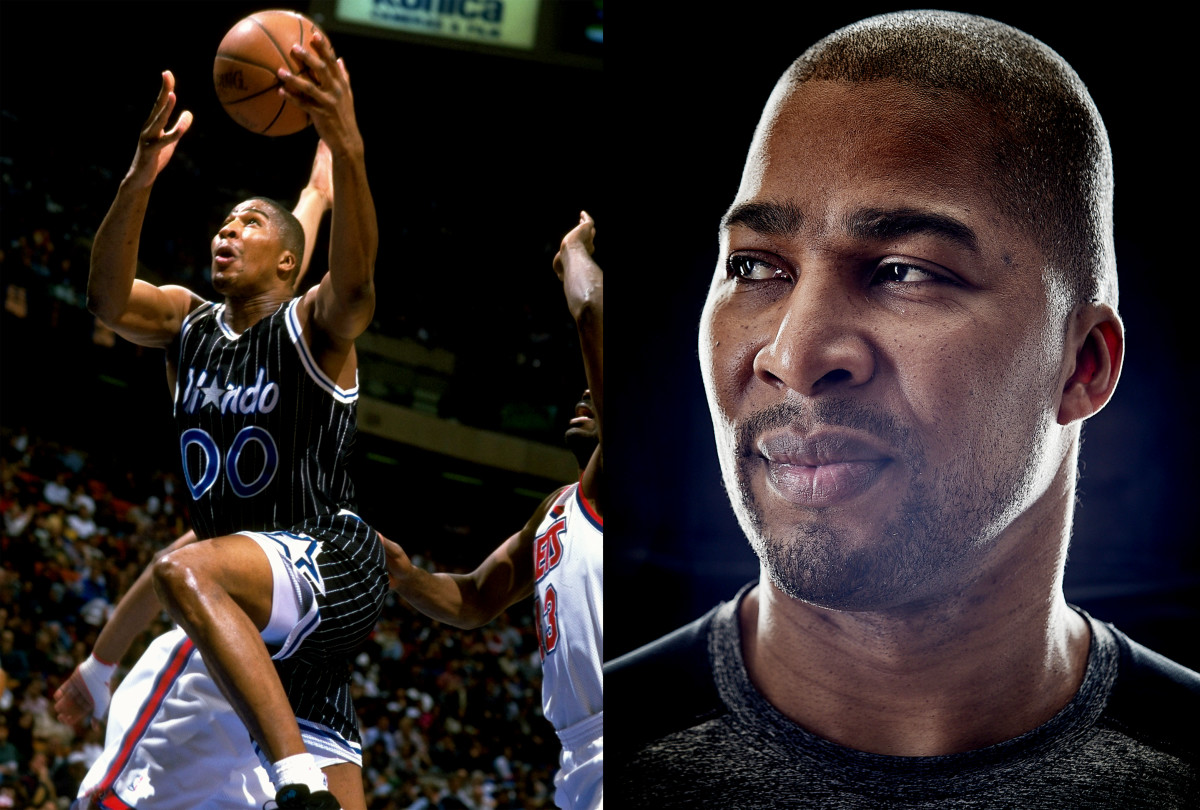

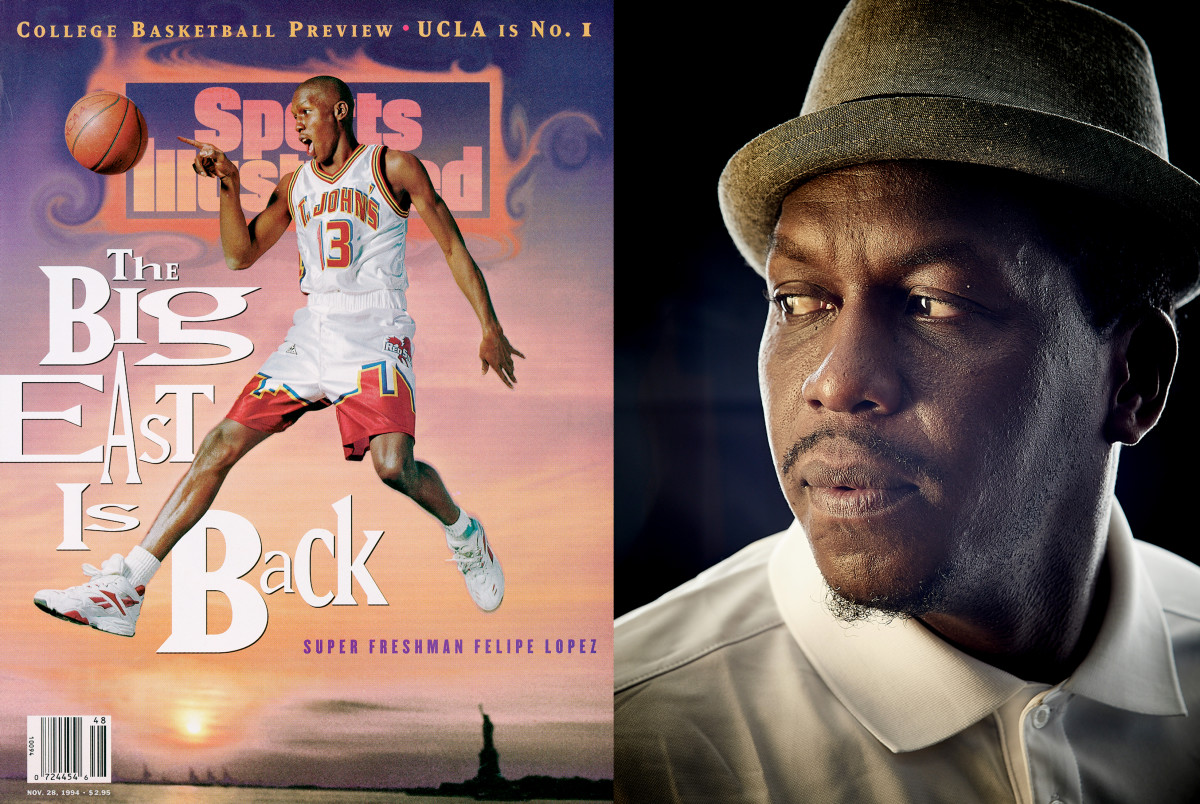

It was as if someone had opened a box of 1990s-era trading cards and started drawing names at random. Strickland, No. 11 on the NBA’s alltime assists list, sat near 60-year-old Ottis Anderson, MVP of Super Bowl XXV (and now head of a marketing firm). Antonio Tarver, 48, once a light heavyweight boxing champ, lounged across from Ki-Jana Carter, the top pick in the 1995 NFL draft (43, marketing). There were former teammates, like Knicks alumni John Starks (51, athletic apparel) and Larry Johnson (48, Knicks exec). And there were dinner pairings who’d never met, like Rodney Hampton, a Pro Bowl running back (48, organizer of a youth camp), and Michael Curry, an 11-year NBA forward (48, coach at Florida Atlantic). More than two dozen in all, they converged on South Florida for a 24-hour session of eating, kibitzing and occasional physical activity.

Nominally, they had gathered at the Boca Grove Golf and Tennis Club for the Rebound Celebrity Golf and Dinner Outing, a benefit for the drug-and-alcohol rehab center that Williams, an NBA All-Star in 1998 who later served 18 months for accidentally killing his limo driver and who is a recovering alcoholic, recently founded. But the event was clearly something more: part cast reunion of a prime-time 1990s TV show, part chapter meeting of an unofficial club. Without being overdramatic, it also had the vibe of a group therapy session.

The occasion enabled a sportswriter to spend 24 hours playing anthropologist, examining an exotic tribe: the retired pro athlete who has moved—sometimes gracefully, sometimes uneasily—into middle age.

2017 Where Are They Now: The After-Party

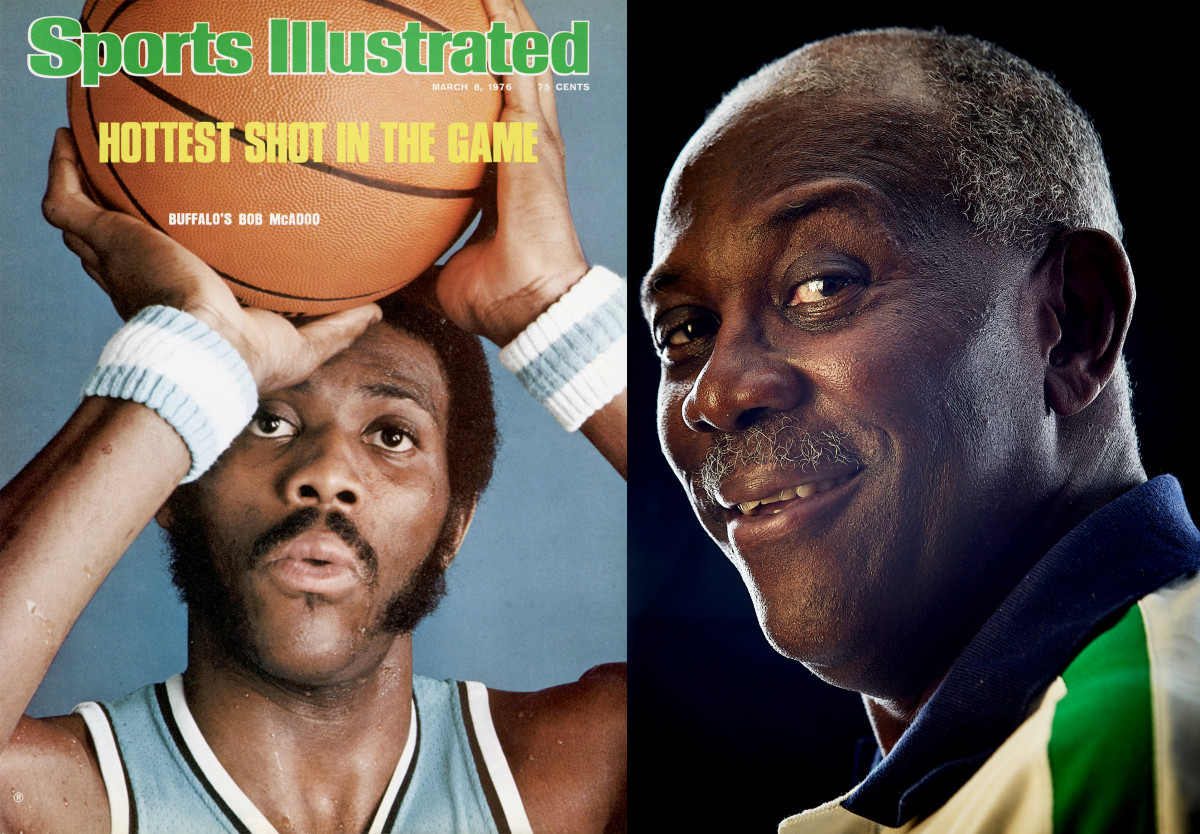

Bob McAdoo

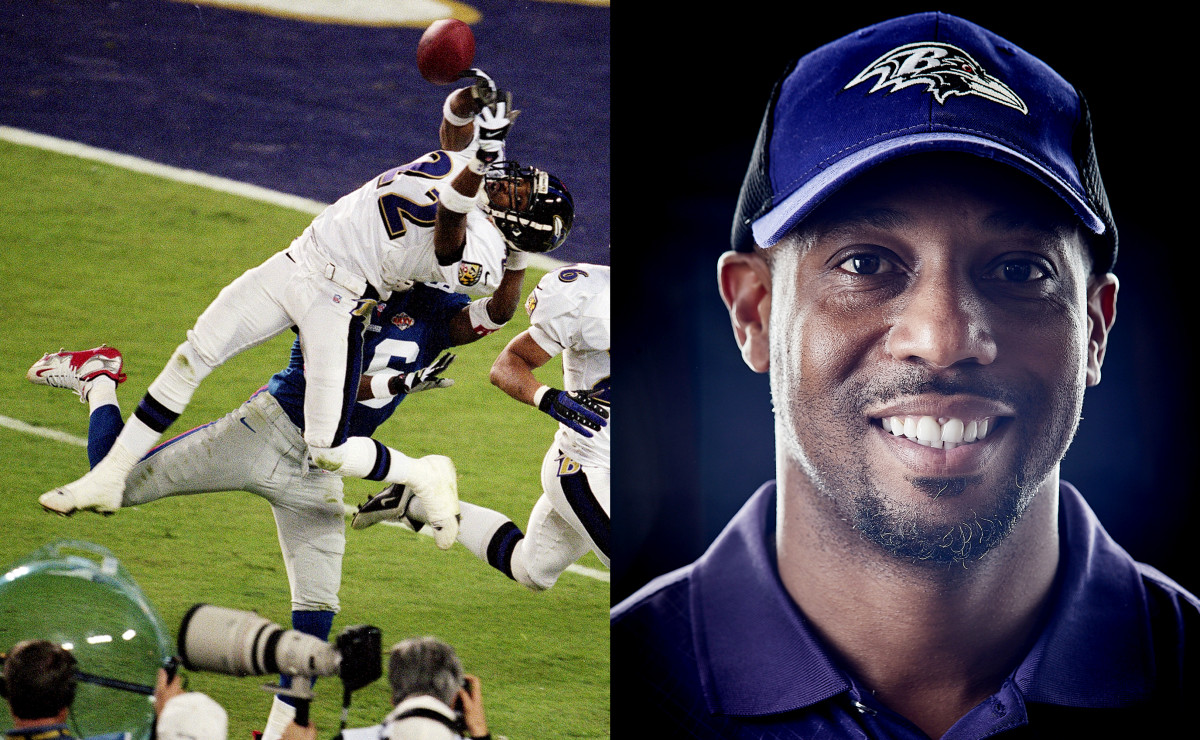

Duane Starks

Johnny Dawkins

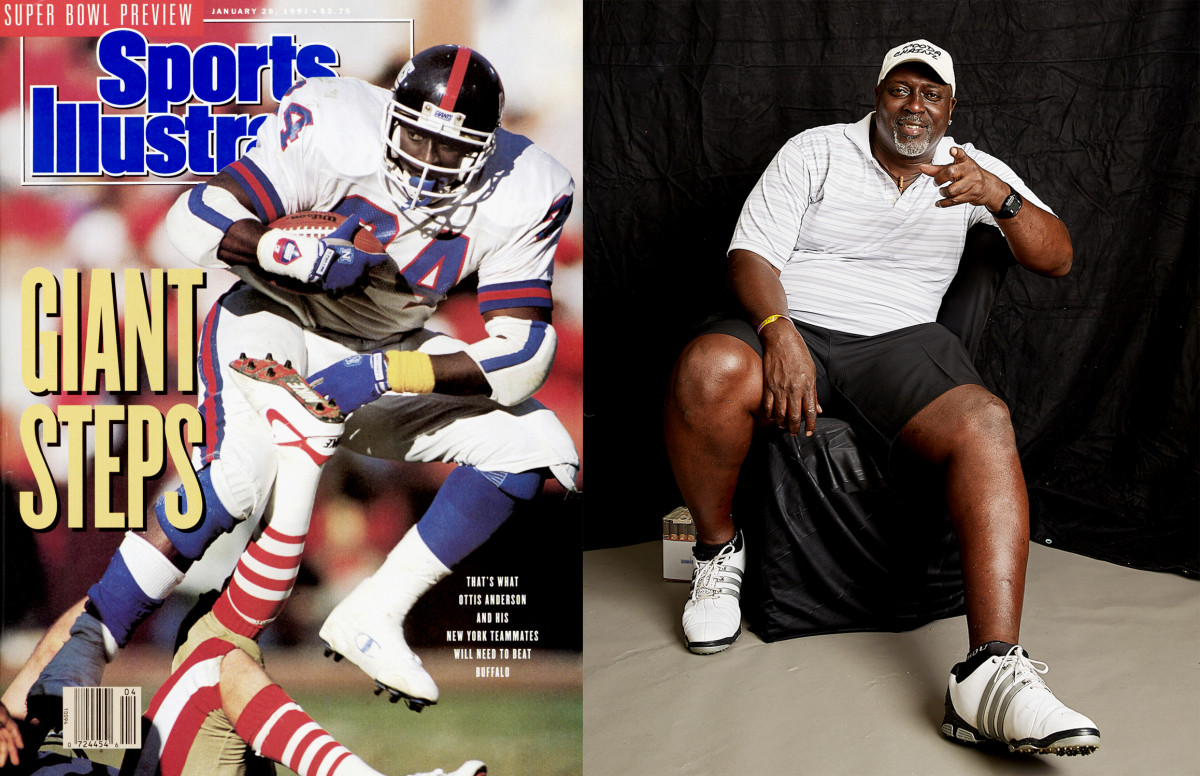

O.J. Anderson

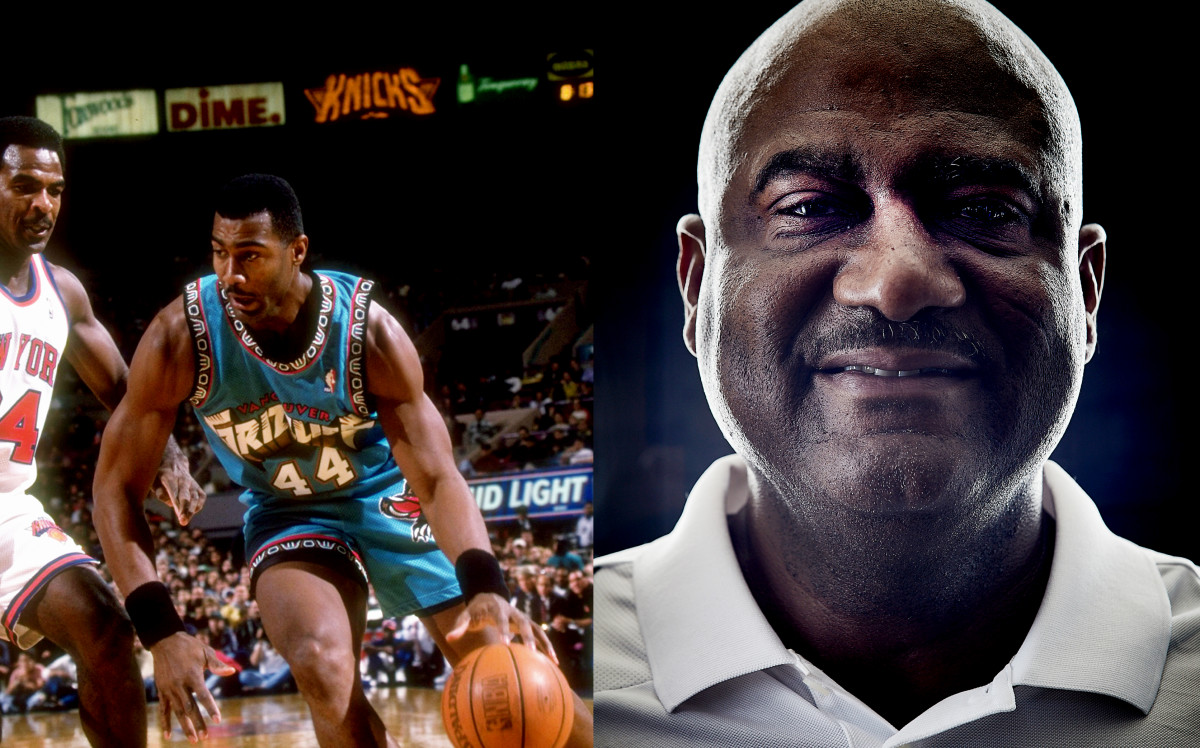

Kenny Gattison

Charles Oakley

John Starks

Pepper Johnson

Rodney Hampton

Jayson Williams

Anthony Avent

Felipe Lopez

*****

It’s an organizing principle of sports marketing and image shaping: Pro athletes, they’re just like us. They, too, simultaneously love their mothers and live in fear of them. They, too, get irrationally competitive playing Ping-Pong. They, too, lose the remote in the couch, lament the line at Starbucks, obsess over their airline status, need to find a charge for their iPhone. But, really, it’s a flimsy trope. It’s not just that pro athletes run (far) faster and jump (far) higher and shoot (far) more accurately than we do. It’s not just that they accumulate experience and wealth beyond the scope of most of the rest of the world. It’s that the arc of their entire existence is so unusual, so at odds with the conventional life cycle. Imagine hitting your peak years—and peak earning power—in your late 20s, retiring in your 30s and then going about the next half century trying to find a comparable experience.

One of the few women at the Boca Raton event, Dana London has spent the last 25 years working with athletes as a “transition expert,” helping them navigate those peculiar rhythms of life after sport. Transitioning “in”—adjusting to a new set of demands and wealth at the onset of a career—is one thing, says London. But the “out” can be just as challenging. Upon retirement, she says, former athletes “are forever remembered as someone they will never be again. There is no going back. They have to develop a new ego for the person they are today.”

Sports Illustrated's Where Are They Now? stories

Sports superstars—Shaq, Jordan, Peyton—tend to be wealthy to the point of abstraction and/or have enough cachet to slide into career 2.0. At the other extreme, the list of athletes who have made a post-career mess of their finances and lives is a lengthy one. But most ex-jocks fall into a soft middle, adjusting to a life in repose at a time when their contemporaries in other lines of work are still early in their careers.

Part of that adjustment entails processing the complicated relationship with their sport. “You want to be sure your life goes on. No one wants to hear, Hey, didn’t you used to be . . . ,” says Strickland, who recently left an assistant’s job at South Florida but is trying to move up the college basketball coaching ranks. “But you don’t turn your back on your passion, you know? My love of basketball didn’t go away when I stopped playing.”

There’s something symbolic about Tarver, who has one foot still planted in the past, the other in the future. Like so many in his field, he has gravitated from boxing to mixed martial arts and now coaches boxing—“stand-up,” in the vernacular—to UFC fighters. Yet he hasn’t officially retired from boxing either. He still considers himself an active pugilist (31-6-1) and stays in shape, anticipating another fight, even if it’s been two years since his last bout.

Others have moved on. Oakley, for one, is now an aspiring chef and caterer. He came early to the Boca outing, entered the club’s kitchen, grabbed an apron and spent the morning making macaroni and cheese, ribs and greens. Told of a skirmish that day in the NBA playoff game between the Celtics’ Kelly Olynyk and the Wizards’ Kelly Oubre Jr., Oakley paused and appeared confused. “You’re telling me,” he said disbelievingly, “that there’s two mother------- in the league named Kelly?”

*****

What do retired athletes discuss when they get together? Health, for one thing, which does and doesn’t distinguish them much from any other cohort of middle-agers. There are the usual dispatches from the battlefield about the ravages of aging and straw polls about procedures being considered. Knee-replacement surgery gets enthusiastic encouragement. (“It really is life-changing.”) Lasik surgery gets a lukewarm recommendation. (“They say it’s 20/20—but my friend says he ain’t 20/happy.”)

But when your past line of work was predicated on physical superiority and peak conditioning, these conversations about the body take on a different dimension. When there are images of you once dunking with your eyes at rim level—see 70-year-old Lamar Green, a genial former NBA forward—restricted mobility can be especially jarring.

Mortality comes up too. In Boca, the names of colleagues and former teammates who didn’t live to see 50 were invoked. The NBA players knew the list cold, like planets in our solar system: Sean Rooks, Dwayne Schintzius, Armen Gilliam. . . . One veteran pointed out how you don’t see a lot of elderly 7-footers walking around—then he pivoted awkwardly: “At least we don’t have to deal with head injuries. That’s some scary stuff.” The NFL retirees nearby either didn’t hear or pretended not to.

As with any reunion, attendees are a self-selecting- group. The ones who aren’t pleased with their station in life—or their appearance—are less inclined to show up. (For what it’s worth, the list of no-shows in Boca included Curtis Martin, Lawrence Taylor, Derrick Coleman and Chris Mullin.) A few of the men appeared typically middle-aged specimens: thinner up top and thicker in the middle than you last recall. But most looked astonishingly fit, with veins climbing their arms like ivy. The 6' 9" Williams claims to have lost 70 pounds over the last year. Johnson looks to be generally devoid of body fat. Strickland, Oakley and Anthony Avent (the 15th pick in the 1991 draft; now the head of a wellness program) are among those who walk around lighter today than their playing weight. And, small sample size though it may have been, this was clear in Boca: The trim athletes maintained their physiques more through exercise than diet. The same men who talked about time devoted to the treadmill ate immodest portions of foods that were—how to put this?—unaligned with optimal nutrition.

How Allen Iverson finally found his way home

Money, of course, is another topic in heavy rotation. Inasmuch as these athletes see themselves as part of a lineage, they are neither princes nor paupers. They struggle to relate to their forebears, who were paid so modestly that they would often moonlight in the off-season. (Someone in Boca made mention of the fact that in his peak earning season, Gale Sayers made only $40,000.) They also speak with awe—sometimes with an emotion verging on bitterness—about the current wage scale. It’s not Russell Westbrook making $30 million next season that riles. It’s the wages of the marginal players—“[Bucks guard Matthew] Dellavedova making almost $10 million? I wish you hadn’t told me that!”—that give pause.

Former athletes have a sixth sense for which of their colleagues are struggling financially. Williams observes that the guy wearing the flashiest clothes and pulling up in the most extravagant car is often the worst off. By the end of the day, three athletes—each in his 40s or 50s—had approached London and floated the possibility of returning to school. (The fact that a B.A. is a prerequisite for an NCAA coaching job has done more than any outreach program to get athletes to finish their degrees.)

The scene in Boca also laid bare this sports truism: Whatever pro athletes are paid, it’s dwarfed by their payment in the currency of narrative. Deep into the night, the athletes told their tales, a sort of story slam. There was the time in the late 1990s that Williams had the guys from NSYNC over to his New Jersey mansion and proffered a bet: If he beat the band’s security guard in a game of pool, Justin Timberlake & Co. would have to perform at Williams’s charity softball game. He did and they did. (The punch line: Williams repaid the favor by gifting each band member an engraved Rolex.)

There was the story about Oakley’s acquiring the pair of sneakers that Jordan wore during his last NBA game, in 2003, when the two men were Wizards teammates. It was suggested that the value of those shoes on eBay today would outstrip Oakley’s NBA pension—at which point Oakley attempted to change the subject.

And did you hear this one about Bill Parcells? One time he screamed at a player during a film session . . . but addressed him by the wrong name. No one had the guts to ask Parcells for clarification. The entire team argued over whether he had the right player and called him by the wrong name or had the right name and misidentified the face. “Regardless,” said the narrator, who asked to remain nameless, “he got two-for-the-price-of-one in terms of getting guys to play their asses off.”

The stories came fast and furious. But they also came tinged with an acknowledgement that the tellers would never replicate the rush they got from playing a sport at the highest level. Not that they can’t try.

Away from the NFL spotlight, financial ruin drove Clinton Portis to the brink of murder

Pet theory: This sustained hunger for competition—along with a comparative gentleness on the body—is why so many former jocks favor golf. Yes, it can be an exercise in humility and humiliation. (Here’s how Hampton put it, before teeing off: “I don’t play golf. I play at golf.”) But the sport rewards power and athleticism and hand-eye coordination and feel and muscle memory. In general, the natural athlete can improve more quickly than the rest of us can; so can those with a pro athlete’s motivation, discipline and hunger for self-improvement. For all the hooks and slices, there tend to come enough plumb-line straight drives and sweet fades that the athlete’s competitive fire begins flaring. “I dream of the senior tour,” says Tarver. “And I know I’m not alone.”

On this day, the guys played 18 holes under wispy clouds in typical South Florida humidity. It was better-ball format, so no one won, per se. But the consensus was that Starks came in for highest honors. (The kind of person who happily shoots 1,000 jump shots after practice? He represents the species that finds success at golf.) As the foursomes returned to the clubhouse, an easy warmth passed among them, an unmistakable sense that all were members of the same elite club.

A familiar golf postmortem ensued, mourning over missed putts and gloating over prodigious drives. Williams, the event’s emcee, played his role perfectly. “Y’all can still use the driving range,” he bellowed. “Actually, most of y’all should use the driving range.” Another round of laughs, and then most of them did just that.

And why not? It wasn’t all that late. They had finished playing, but there was still plenty of daylight left.