Generation Shaq: Catching up with the kids named after a larger-than-life NBA superstar

The young woman wandered through the bookstore near the neighborhood mosque, up and down the aisles, searching for a name. She was almost 18 years old and almost nine months pregnant with her first child. The perfect name would feel empowering. It would also convey courage; a single mother, she and her son needed to be strong together. She saw him becoming a role model. She hoped he could accomplish big things.

The baby was born on March 6, 1972, at Columbus Hospital in Newark, N.J., and weighed seven pounds, 11 ounces. For his middle name, the mother chose Rashaun. “Warrior,” according to a book of names she found. A few pages later, under the next letter—S—she found his first name. “Little one,” read the adjacent interpretation, she recalls, though fluent speakers today might say it means “shapely” or “handsome.”

In any case, the boy hated his name. Teachers couldn’t pronounce it; classmates mocked it. Then his stepfather, an Army staff sergeant, got transferred to Germany. A fresh start, so the boy began going by J.C., which stood for Just Cool.

One day, playing outside, someone hollered for J.C. Overhearing this, his stepfather stomped over and snatched his collar. “You better be proud of your name,” the boy was told. “Your name’s going to be famous one day. Everybody’s going to know the name Shaquille O’Neal.”

Shaquille O’Neal Long cannot remember when the Jeep pulled into the driveway and his namesake knocked on the front door. Granted, he was barely three months old that morning in January 1991, still wearing his infant-sized church clothes after returning from Sunday services. His parents didn’t know about the surprise headed their way either, but word had gotten around greater Baton Rouge that one family christened their son after the backboard-busting sophomore at nearby LSU. After the birth, a sign blared from the marquee outside the middle school where Ernest Long worked: HOME OF LITTLE SHAQUILLE O’NEAL LONG.

That was enough to summon the big guy himself, ducking through the doorframe, bearing gifts of basketball jerseys and bibs. “Can we get a picture of you holding him?” Long asked, so they posed by the Jeep. “And a picture of him by your shoe?” So O’Neal slipped off one of his size-22 sneakers, bigger than little Shaq by several inches.

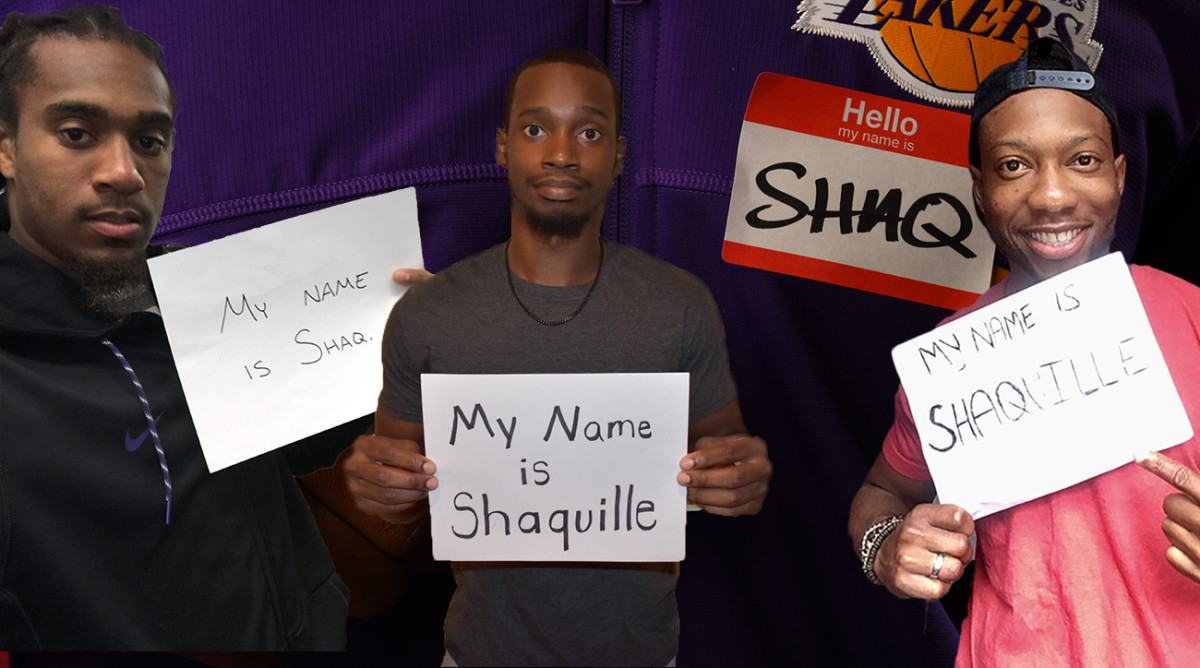

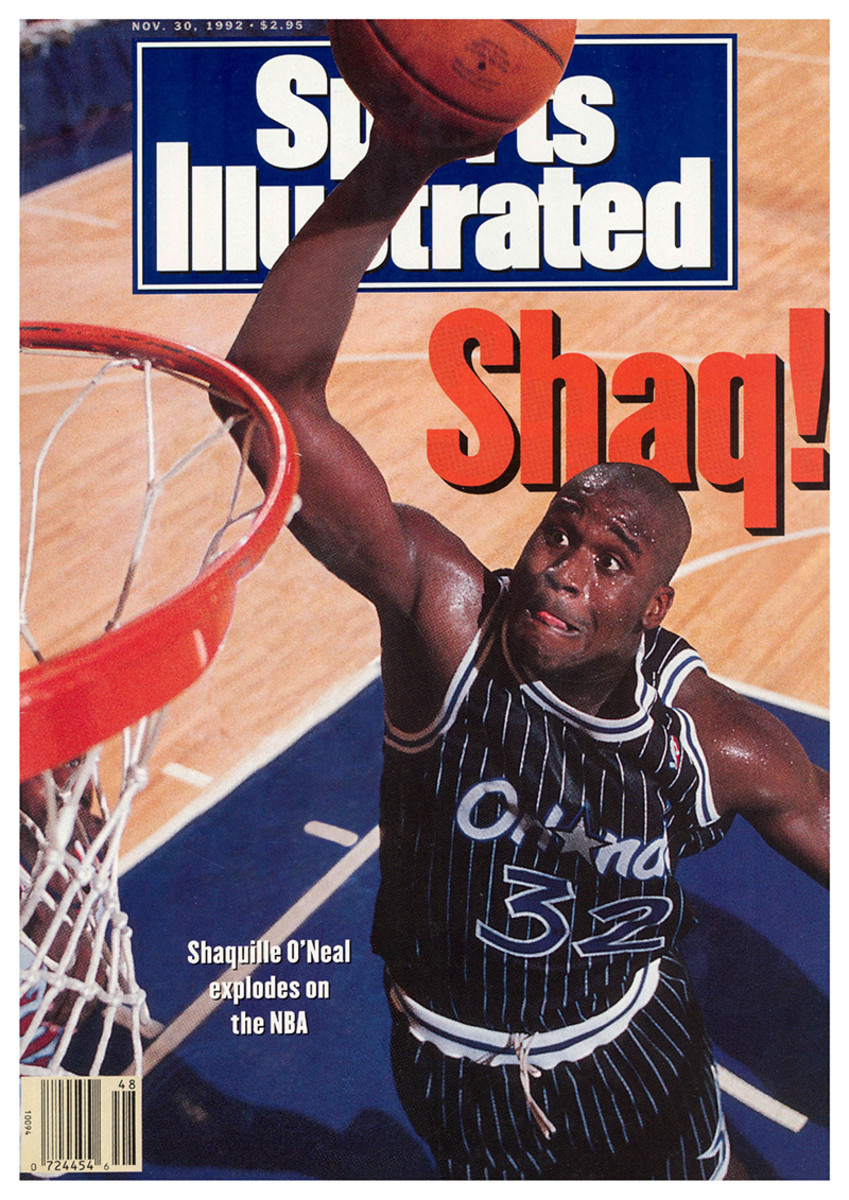

In 1992, the year the Magic drafted O’Neal first overall, his first name ranked No. 426 among nationwide male births, according to the Social Security Administration. In 1993, the year O’Neal was Rookie of the Year, 1,784 boys were named Shaquille, for an average of five newborn Shaqs each day, and the name vaulted to No. 181. Over time O’Neal would learn about families just like the Longs. Parents shared their stories at the grocery store. Google Alerts for other Shaquilles pinged into his phone. A second generation formed.

“I’d probably guess around 250,” O’Neal says. His reaction when told the real figures: “Holy s---. Seriously? My God. Damn, that’s crazy.”

Now the millennial Shaquilles are making names for themselves, graduating college and entering the workforce. Searching “Shaquille” on LinkedIn yields 2,154 results; 526 profiles match “Shaq.” They are clarinetists and youth pastors and math tutors and aerospace engineers. One is a paralegal for the U.S. National Guard. Two helped build race cars from scratch for college competitions. One spent a year and a half reporting on the 2016 presidential race, during which Wisconsin governor Scott Walker would call on him during gaggles by asking simply, “Shaq?”

Shaquille Omari delivers groceries through the app Deliv, so when customers see his first name and last initial, they often open the door and say, “Shaquille O’Neal is here!” Evade any tolls recently in New York City? Chances are good that Shaquille Gurley noticed from his data analytics position with the Port Authority. Shaquille Jones played tuba in the marching band at Tennessee. He didn’t encounter any other Shaquilles over four years in Knoxville, but another famous name stood out: “Met about five or six Peytons,” he says.

Some Shaqs are in the club by chance, like Shaquille Townsend, whose father knew nothing about O’Neal’s success while stationed at an Air Force base in Japan and heard the name from a friend. But these are outliers. Of the 40-plus Shaquilles interviewed by SI, all but two said their parents’ choice was inspired by the rim-rattling, joke-cracking, rapping, Kazaam-ing, 7' 1", 300-plus-pound center. “We’re always going to live in the shadow of Shaquille O’Neal,” says Shaq Thompson, the Panthers linebacker. “That’s the original. That’s our inventor.”

As an October 1990 birth, Long considers himself among the first. Which means he heard all the one-liners from classmates and got all the DMV double-takes before anyone else. “There was a rumor that Shaq was my godfather,” he says. “I don’t know who started it, but I let it slide.” He bought Shaq Attaq sneakers because his name was stitched into the heel. The plates on his black 2014 GMC Sierra Denali say SHAQL. It was his girlfriend’s car, though, that once got pulled over with Long behind the wheel. Eyeing his license, the officer said, “Shaquille O’Neal, huh? You got the whole name?”

Long, a production manager for a manufacturing company, still lives in Louisiana. Fifteen years after the home visit, he and O’Neal crossed paths again, over lunch at a Baton Rouge barbecue joint. Long asked for a picture when O’Neal finished eating but didn’t want to bother him further by bringing up the size-22s. Of course, O’Neal never forgot. He still remembers what he realized as his Jeep pulled from the Longs’ driveway:

“I think I’m a superstar now. People are naming their kids after me.”

Aaron Shaquille McCain was nearing his second birthday when the May 1996 issue of Ebony hit mailboxes, a lovely family photo splashed across its cover, next to the accompanying headline, “Shaquille O’Neal: Superstar Pays Tribute to His Supermom.”

After reading the article in her southern Virginia home, Karshena McCain felt inspired to pen a letter to the editor, which Ebony published later that summer. “I, too, am a single parent,” she wrote. “[My son] was named after Shaquille O’Neal, and I hope I have the strength to instill the qualities of responsibility, loyalty and the down-to-earth nature Mrs. Lucille Harrison has instilled in Shaquille. . . . I hope that my Shaquille and I will share that very special bond also.”

It wasn’t just O’Neal’s brute force and overwhelming talent on the court—in his first four seasons he won an NBA scoring title and played in four All-Star games—but his joyful personality and mama’s-boy charm that turned McCain toward the name. “He couldn’t get through an interview without a joke, or a prank, or some type of corny comment,” she says. “And I just remember thinking, ‘I love this guy.’” Certainly her Shaq shares the hallmark goofiness, whether busting out dance moves or belting karaoke. (“Go-to song?” he says. “Top three: ‘Party in the USA’ by Miley Cyrus, Taylor Swift’s ‘Shake It Off,’ and Beyonce’s ‘Single Ladies.’”) And the tender side. In high school, when his mother was balancing three jobs, he offered to help cover expenses by getting one too.

Now 22 years old and a recent graduate of UNC Charlotte, Shaq McCain works for an area auto-detail service, washing players’ cars during Hornets games. He also likes reading about O’Neal’s many investment ventures—restaurants, movie theaters, an esports team—and thinks about entering the business world. “I try to follow him as much as I can,” McCain says.

Like Karshena McCain, plenty of parents hoped their progenies would follow in the Original’s oversized footsteps—and not just on the basketball court. After his freshman year in college, Shaquille Odom was contemplating dropping out and taking a high-paying job hosing down oil tankers. So his parents sat him down and said, “Just think about Shaq.” Specifically, think about how O’Neal stayed at LSU for three years before turning pro, but later earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. The desire to pursue education was why the Odoms named their son after him in June 1991—and why Odom decided not to leave school almost two decades later. “Without Shaq,” he says, “I don't think I’d be who I am today.”

Shaquille Shelby finally entered this world after his mother spent 24 hours in stubborn labor. In pain and exhausted she trusted his father to oversee the early parenting tasks, such as inking the first footprint and picking the name. Shelby’s mother had suggested Richard, after her father. “If you’re going to go against my mom’s word, you better have a good reason,” Shelby, now 22, says. And that was . . . ? “He thought it’d be cool because, well, Shaquille O’Neal was doing big things. No pun intended.”

Some families take their tributes even further, which isn’t always welcome. “I told myself that I would get rich and the first thing I’d do is change my name,” says Shaquille O’Neal Minnifield. “My first name, I was always cool with it. It was the middle one that put the icing on the cake. I can’t be going around associated with this bald-headed, ugly dude.”

Then there are those whose parents didn’t foresee the ramifications of their name choice. “It was kind of rough, not going to lie to you,” says Shaquille Allante O’Neal, 24. “I’m 5' 5".” To avoid association, his Facebook page used to display his middle name instead of his last. But when he tried updating to the full thing this year, Facebook asked him to send a photo ID as proof. “They said, ‘Sorry, we don’t believe that’s your real name.’”

Imagine then the eyebrows raised at Shaquille Huang, 23, whose family moved from the Philippines to Alaska when he was seven. “I was an Asian Shaq living in Anchorage,” he says. “And I played hockey.” He’s not alone—the name doesn’t restrict to one race or gender. “Having other female friends named like Sarah or Ashley, I wanted a name like that,” says Shaquille Paige, 25. “But as I got older, I realized everyone has their own uniqueness.”

Shaquille Christmas, 23 and works in a vaccine lab, hails from Trinidad; grad student Shaquille Rolle, 23, from the Bahamas; Shaquille Dawson, the United Kingdom. Each reported similar epiphanies after immigrating stateside: Their name was way more popular than they thought. “I asked my teacher, why are these kids looking at me weird during roll call?’” Rolle says. “She had to tell me what the name meant.”

A product of inner-city Newark, not far from where the bookstore and the mosque once stood, Shaquille Jones-Knight, 24, experienced something different. Each fall his Pop Warner football teams typically rostered at least one other Shaquille. Then he went to prep school in western Maine. “First time being around predominantly white people,” he says. “It was definitely a culture shock. Obviously my name stood out more, but it was a huge icebreaker with people that I probably wouldn’t normally hang out with.”

Shaquille Pariag, 26, felt like a military brat as a kid, moving every two years because his father sold insurance. In this way Pariag can relate to Huang, who hopscotched from Anchorage to Los Angeles and currently lives in the Bay Area. But they share an even deeper bond too:

Each has a younger brother named Kobe.

How Allen Iverson finally found his way home

Shaquille Baptiste jolted awake to the sound of an iPhone alert. He had dreamed about this moment ever since he began emceeing as a teenager in downtown Toronto, under the stage name ShaqIsDope. Now, late in the summer of 2013, the reward for his faith had finally arrived, glowing there on the lock screen: @SHAQ is following you on Twitter! “I just knew,” Baptiste says, “that one day he would find me.”

Much to his shock, the admiration was mutual. Upon discovering one of Baptiste’s early music videos on the website WorldstarHipHop, O’Neal fired off some flattering direct messages—“just saying you really are f---ing dope,” Baptiste recalls—before dropping the bombshell request. Would Baptiste want to collaborate on a remix of “Karate Chop,” the Lil’ Wayne and Future joint? Could they make rap history together, an emerging talent joining forces with a once-platinum artist who released four studio albums, Shaq feat. Shaq?

An incomplete version of the song soon pinged into Baptiste's inbox. Then 20 years old, he rushed to the studio, cut his verse within three days, and emailed the completed product back to O’Neal. “You killed it, homie,” came the reply. “Keep bringing life to the name.” The track was released online by Complex magazine. At first, it drew skepticism. “Little-known Toronto rapper ShaqIsDope deserves some credit for his ingenuity,” read one review, “assuming it’s a fake.” But not even seasoned spoofers could’ve scripted lyrics like the real Shaq:

Sometimes I question what you rappers spitting

You know in the post your ass is barbeque chicken

Don’t need to go platinum, that’s what you rappers do

I’ll tweet this verse, that’s 8 million views.

“A lot of doors opened up after that,” Baptiste says. Six months later, he flew to New York City and met with several record labels. “Well, you brought Shaq out of retirement,” one exec told him, “so you must be a good rapper!” In March he performed a 20-minute showcase at South by Southwest. His single “Stay Focused” reached four million streams on Spotify in June. He plans to release his new EP this summer. Naturally, it’s self-titled.

“ShaqIsDope,” O’Neal says. “That’s a nice name. Wish I would’ve thought of that.”

The after-party: Inside the life of the modern professional athlete in retirement

Shaquille Walker kept some clever childhood friends. Short, skinny and lacking in basketball talent, he was tagged with the nickname, Qahs. “Because I was the exact opposite of Shaq,” the 5' 10", 140-pound professional middle-distance runner says. “The only similarity, I guess, is our free-throw ability.”

Sobriquets were always O’Neal’s specialty. The abbreviation—Shaq—came first, reminiscent of the former NC State forward-center Charles Shackleford. Then: Shaq-Daddy, Shaq-Fu, Shaq Diesel, Super Man, Big Shamrock, Big Aristotle (his favorite, for the record). . . . Has any athlete ever generated sweeter nicknames than the Big Agave?

The secondary Shaquilles have inherited these—among Huang’s most treasured possessions is an autographed Heat baseball cap: TO THE LITTLE DIESEL, FROM SHAQUILLE O’NEAL—and inspired more. After recovering from the prolonged birthing process, Shelby’s mother took to calling him Shaq-a-Doodle. “I had so many nicknames,” says Shaquille Price, a former walk-on cornerback at North Carolina who answered to Shaqtin’ a Fool. “I can’t even remember right now.”

This is the cool part. The annoyances? Spelling and pronunciation. Trips to Starbucks and Smoothie King are nightmares. So was the first day of school. Common rollcall butcherings include sha-KWEEL, sha-KWILL, sha-KWY-lee, and shock-you-ILL. “Anytime there’s a substitute teacher,” Pariag says, “I made a game out of it. What are they going to call me?” And once they learn, every question is the same. Software developer Shaquille Brooks, 24, used to work in IT support. Roughly half of his 20 to 30 daily calls followed the same pattern:

Hello, my name is Shaquille, how may I help you?

“How tall are you?”

“Do you play basketball?”

“Are you related?”

*facepalm*

Shaquille Heath strode across the carpet and found her seat on the stage. It was May 1, 2015, at Weber State University, and for weeks the senior public relations major had been rehearsing her commencement speech in front of the mirror in her off-campus house. Still she felt nervous, even if one of her fellow speakers was decidedly not. When she asked how much he had prepared, Damian Lillard coolly replied, “I haven’t. Just gonna go up there and wing it.”

The laid-back Portland point guard could be forgiven for ad-libbing; less than 36 hours earlier, Lillard and the Trail Blazers had been eliminated from the first round of the playoffs. But winging things was never Heath’s style. In high school she was on the drill team and edited the yearbook. She graduated from Weber State with a 3.98 GPA, summa cum laude, all A’s except for an anthropology class that she retook after getting a B the first time. “I’m an overachiever,” she says.

Behind the mike at Dee Events Center, she took a breath and then explained why. “Unfortunately, my birth parents were drug addicts, and their addiction took over so much of my childhood,” Heath told the packed crowd. “Sometimes I didn’t have a place to sleep. Sometimes I went hungry. And at most times I was alone.” On some level these hardships vanished over holiday break in eighth grade, when Heath began living with her best friend’s family. But she never forgot the struggles. For better or worse, her birth parents helped shape her identity. They motivated her to become something different, to avoid that life.

They also gave Heath her name.

“Oh, it was so annoying,” she says. “Everyone automatically assumed I was a boy.” At first the teasing was embarrassing. One doofus in high school propositioned her to “Shaq-attack his pants,” she recalls. “I was so mad. I was not having that.” (Other pickup lines she finds more creative, like a musician who tried, “If you be my Shaq, I’ll be your Kobe.”) Uber drivers are usually taken aback when a 23-year-old woman climbs into their cars, despite her picture appearing on the app. And quite the confusion stirred at Weber State when its graduation speakers were billed as “Shaq and Lillard.”

The pair met before the ceremony. Heath snapped selfies and complimented the style of Lillard’s socks. He raised an eyebrow upon learning her name but didn’t inquire further. If he had pressed, she might’ve told him what she realized over time: “It’s a f------ rad name,” she says. “So memorable, so popular. It’s a blessing. It makes me stand out.”

To Heath, being around Lillard offered a glimpse into her namesake’s world. “I do feel a huge connection with him,” she says of O’Neal. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve decided, I’m going to tweet him for a straight hour, and he’s going to have to see it and have to respond.”

Like on April 7, 2015, less than a month before graduation:

11:39 A.M.: Everyone always thinks I'm a guy but on the contrary, I am a very small girl. @SHAQ

11:40: I tried to play basketball in middle school. I didn’t make the team. I suck @SHAQ

11:42: Everyone I know calls me Shaq. They think its the coolest name ever. So thanks for that. @SHAQ

11:44: When I was in first grade- There was a kid named Josh O’Neal. Everyone said- “If you guys get married, you’ll be Shaquille O’Neal!” @shaq

11:44: So of course, I hated him. @SHAQ

Shaq Mason enters the Gillette Stadium media room on a sweaty late-April afternoon, nine weeks removed from the Patriots’ dramatic Super Bowl LI win, in which New England took 99 offensive snaps and Mason lined up at right guard for all of them. He celebrated by returning home to Columbia, Tenn., visiting family and reading Dr. Seuss books at his old elementary school. Someone suggested throwing a parade, but Mason nixed that idea. “I don’t need all that attention,” he says, though he did agree for March 4, 2017, to become Shaq Mason Day.

Of course, had the city employed his full name, it would have been declared Shaquille Olajuwon Mason Day. “My mom was a huge basketball fan,” he explains with a shrug. When Mason was 12, he went to a Grizzlies-Heat game in Memphis. Hanging out courtside, someone spied his number 32 black Miami jersey. “What’s your name?” the man asked. Before Mason knew it, he was shaking hands with O’Neal.

Because the Patriots opened the 2015 season on a Thursday night, Mason narrowly earned the honor of becoming the first Shaquille to appear in an NFL game, beating Thompson by three days. A five-star football prospect out of Sacramento—and an 18th-round pick by the Red Sox—Thompson would search himself on recruiting websites and invariably find other Shaqs. “Damn!” he recalls thinking, less bummed out than bowled over, “there are more out there!”

Only a select few have grown into professional athletes. No Shaqs have yet appeared in the NHL, Olympics or MLB. Only four—Mason, Thompson, Bills defensive end Shaq Lawson and Broncos linebacker Shaquil Barrett, who won the first Shaquille Super Bowl ring by beating Thompson’s Panthers in 2016—have made the NFL. College odds are better; sports-reference.com lists 39 Division I football players and 23 D-I basketball players named Shaquille, Shaq, or some phonetic derivation.

Though two have suited up for D-League squads, the NBA too remains void of subsequent Shaquilles. In fact, only one has ever been drafted into a major North American pro basketball league: Schaquilla Nunn, a third-round pick by the WNBA’s San Antonio Stars this April. “I love my name,” says Nunn, a forward who played at Winthrop and Tennessee. “The only thing that I would never settle for was being called Shaq. I think people trying to press that on me, call me by that name—that’s not who I am. It just doesn’t fit me.”

Reaching the highest level means access into an exclusive club. Benefits: access to the Original. When Mason played at Georgia Tech, he visited O’Neal at TNT’s Inside the NBA studio in Atlanta, and the two exchanged numbers. After Super Bowl 50, O’Neal hit up Thompson on Twitter. “He was like, ‘Good to see you holding it down for the Shaqs,’ ” Thompson says. “I delete every message, but I honestly wish I still had that one.”

To O’Neal, staying in touch is important. When he was their age, conversations with Jerry West and Magic Johnson and Bill Russell prepped him for fame and success. So he watches the Shaquilles closely. “I see what they’re going through,” he says. “I try to give them tips. If I can help these guys become the best ever, I’d like to do it.”

Shaquille Alexander and Shaquille Brewster were total strangers until meeting minutes ago, but they quickly find common ground in this sixth-floor conference room at the Westin Cleveland. For one thing, both have been victimized by typos. When Alexander was adopted by his uncle, the custody papers said Shaquilla. Brewster’s birth certificate meanwhile reads Shaqville, which sounds like some sanctuary city for all the namesakes to commiserate.

“I hate how people pronounce it,” Alexander says. “I got Shaniqua once.”

“Do you get the people who ask, Is it O.K. if I call you Shaq?” asks Brewster.

“Someone at my part-time job uses the long a. Very nice lady, but she calls me Shake.”

“This is like therapy.”

“People talking about if I play basketball, about how I’m tall but not tall enough . . . ” Alexander’s voice trails off. He looks at the door. “Omigod. There he is.”

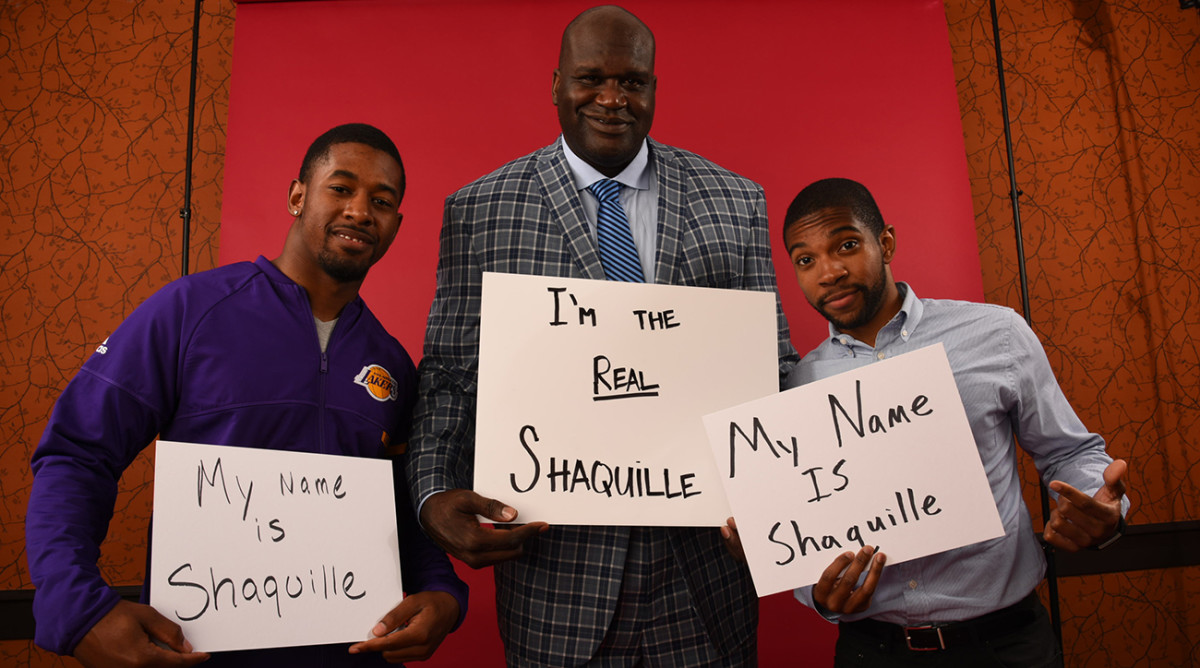

The Summit of Shaquilles—arranged for this article—has begun. With O’Neal already in Cleveland for Game 4 of the NBA Finals on June 9, a call went out for area namesakes. An NBC News producer based in Chicago, Brewster, 24, was assigned to cover the Cavs-Warriors series anyway but hustled straight from the airport. Dressed in a purple Lakers jacket, Alexander, 21, drove two hours from Columbus, where he coaches high school football and majors in finance at Otterbein University, for the “chance of a lifetime.”

Every day brings word of more. Shaq Morris declared for the NBA draft without an agent but withdrew before the deadline and will return to Wichita State for his senior season; Shaquill Griffin went 90th overall to the Seahawks in April. Recently O’Neal found a rapper named ShaqKills and planned to reach out like he did with Baptiste. He had never met a female Shaquille until hearing about Heath’s futile Twitter efforts. So he dialed her on FaceTime, right there in the conference room.

“Say hello,” he says, pointing the phone toward Alexander. “His name is Shaquille.” And then at Brewster. “That’s another Shaquille. Option No. 2...

“Wanna make history?”

No, he’s not the only hoopster with thousands of progenies running around; Kobe has lived in the Social Security Administration’s top 600 for the past two decades, and Jalen became wildly popular after Michigan’s Fab Five era. But O’Neal has embraced his generation like no one else. “When I was coming up, it wasn’t a common name,” he says. “It was sort of like a freak name. I guess parents saw somebody who was likable, someone who was real. Just honored to have them named after me, youngsters with the same aspirations and dreams.”

Alexander was born in April 1996, the tail end of the boom, when the name spent its final year in the SSA’s top 1,000 rankings. But perhaps Shaquille will make a comeback. As O’Neal lumbers away to Quicken Loans Arena for Game 4, Alexander reaches an epiphany:

“Got to name my kid Shaq Jr.”