Who Needs the Other More: High School Phenom LaMelo Ball or the NCAA?

Who needs the other more: high school basketball phenom LaMelo Ball or the NCAA? We’ll soon find out.

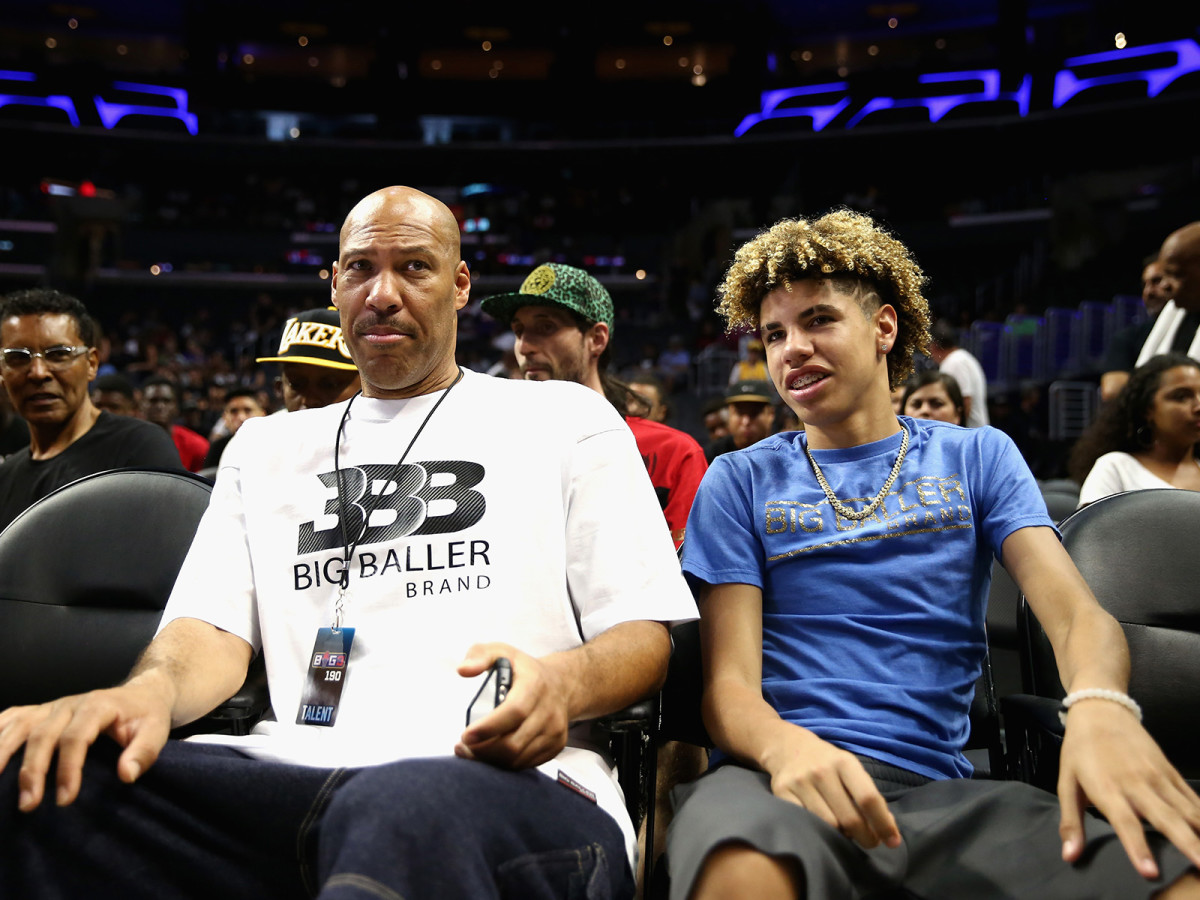

Ball, the 16-year-old son of Big Baller Brand (BBB) CEO LaVar Ball and younger brother of Lakers rookie Lonzo Ball and UCLA freshman LiAngelo Ball, has “meticulously designed and inspired” a sneaker that is named after him. The “MELLO BALL 1” or MB1 is available for sale on BBB’s website for $395. BBB hails the MB1 as “the first signature shoe launched by a high school basketball player.”

Ball has taken to social media to promote MBI, including in a BBB advertisement in which Ball wears a pair of MB1s, talks about how “old people just don’t get it” and drives a Lamborghini in an affluent neighborhood. LaMelo is the second Ball brother to have a shoe promoted by BBB. Older brother Lonzo has inspired several BBB shoes including the “ZO2: SHO'TIME!,” which sells for $495.

LaMelo Ball’s value to UCLA

LaMelo Ball may only be 16, but he is already a public figure and a highly marketable athlete. At age 13, he followed in his older brothers’ footsteps and committed to play at UCLA. Ball is currently a junior point guard at Chino Hills High School (Calif.). He is set to join UCLA in the fall of 2019. ESPN ranks the 6’3" Ball as the seventh best high school recruit for his class. Other basketball ranking services are similarly optimistic about his future.

If Ball continues his impressive development, he would declare for the 2020 NBA Draft. Ball cannot join the NBA earlier due to Article X of the NBA’s collective bargaining agreement. Article X dictates that for an American player to be draft eligible, he must be at least 19 years old and at least one NBA season must have elapsed since when he graduated from high school or, if he didn’t graduate, when he would have graduated.

A lot can happen over the next three years. Ball’s progression as a player might stall. There are supposed weaknesses in his game, including that he isn’t as athletic or as explosive as Lonzo. And, like many young players, Ball’s defense remains a work-in-progress. Those weaknesses may become more problematic as he faces faster, larger and more polished competition. There’s also the unpredictable wildcard of continued health and avoidance of serious injuries.

The Kyrie Trade Was the Only Move Left for the Celtics

Still, as the world sits in September 2017, LaMelo Ball appears likely to enter the NBA in 2020. He thus has three years to prepare for NBA commissioner Adam Silver calling his name to the stage and congratulating him on being drafted.

Ball’s projected year at UCLA, then, is his final developmental step before entering the NBA. That’s not to say his year in college would entirely concern basketball. Ball would be required to take a semester’s worth of classes and pass those classes. As someone who teaches college students, I’d like to think that one semester of college coursework is better than none.

Yet there’s no doubt that Ball’s brief time at UCLA would clearly be devoted to basketball. Along those lines, once the Bruins’ season ends in March 2020, Ball would leave school and diligently prepare for the NBA draft.

Although UCLA would prefer that Ball stay longer than one season, one year of Ball is possibly worth more to UCLA than four years of any other UCLA student. He is already a celebrity from a celebrity family. If his game progresses as expected, he would be a star as a freshman. Fans would pay money to watch him play in person at Pauley Pavilion. They would be more inclined to buy Bruins merchandise and apparel. TV ratings for Bruins games would climb.

Ball’s presence at UCLA could also help the university’s admissions office recruit academically gifted high school students. Some high school seniors admitted to UCLA might become more inclined to pick the school over other colleges offering admission because of their excitement about the Bruins basketball program with Ball leading the way. The UCLA Development Office is probably also thrilled by Ball’s pending presence.

With Ball in the fold, UCLA alumni who are basketball fans might become more engaged in their alma mater’s affairs—and thus more likely to donate money to UCLA. So for UCLA, one year of LaMelo Ball is clearly better than none.

An ill-suited fit with NCAA rules

While UCLA obviously wants Ball, the NCAA could stand in the way. Ball’s MB1 sneakers could prevent him from complying with NCAA rules.

Article 12 of the NCAA Division I Manual dictates that “an individual loses amateur status and thus shall not be eligible for intercollegiate competition in a particular sport if the individual (a) uses his or her athletics skill (directly or indirectly) for pay in any form in that sport; [or] (b) accepts a promise of pay even if such pay is to be received following completion of intercollegiate athletics participation.”

Article 12 is one of the reasons why many pro basketball players from other countries are ineligible to play Division I men’s basketball: they were paid as basketball players before attending a U.S. college and the amount of their pay exceeded what would plausibly be used for educational expenses.

For Ball, if BBB has paid him for his role in “meticulously” designing and inspiring the MB1 sneakers, or if Ball has been promised pay once he finishes his time at UCLA, he may have already violated Article 12. A violation would occur if paying Ball for his involvement and promotion of a basketball sneaker counts as “for pay in any form” in basketball.

In response, the Ball family might say “not so fast.”

First, Article 12 contains a notable exception. Players can maintain their NCAA eligibility when their pay prior to college was for “modeling” and other “non-athletically related promotional activities.” These activities include use of one’s name or picture “to advertise or promote the sale of a commercial product or service.”

Perhaps Ball could insist that his shoe deal is much more about fashion and style than it is about basketball. A good portion of the aforementioned MB1 advertisement shows Ball eating cherries from a lounge chair and driving a Lamborghini around what appears to be Chino Hills. At its core, maybe the MB1 is about “California lifestyle,” not basketball.

Along those lines, Ball is an actor, of sorts. He stars in a Facebook reality series about his family called Ball in the Family. Ball also has an IMDB page and he recently appeared alongside his brothers and dad on WWE Raw. If Ball could convince the NCAA that his relationship to a sneaker contract is about his celebrity, not about his athletic ability, he may be able to continue his involvement with BBB sneakers into college.

The Awkward Dynamic Between Derrick Rose and the Cavaliers

Such an argument for invoking this exception wouldn’t be easy, however. The exception requires that the athlete “became involved in such activities for reasons independent of athletics ability” and that the athlete “does not endorse the commercial product.” Ball likely could not meet such requirements. Even if MB1 is partly about lifestyle, it is marketed as related to his basketball abilities. Ball has also endorsed the MB1 in an advertisement that depicts him shooting basketballs.

But Ball is not necessarily out of luck. Article 12 also allows an athlete to insulate his or her NCAA eligibility from the impact of previous advertising, recommending or promotion “of the sale or use of a commercial product or service of any kind.” It does so by directing the athlete to take “appropriate steps upon becoming a student-athlete to retract permission for the use of his or her name or picture and ceases receipt of any remuneration for such an arrangement.”

This language could be read in a favorable light for Ball. If prior to matriculating to UCLA Ball disassociates himself from footwear and other commercial products that are currently linked to him, he would seemingly be compliant with Article 12. But as mentioned above, the NCAA might contend that compensation for MB1 constitutes impermissible “pay in any form.”

One thing is clear: UCLA can’t get around Article 12. UCLA must certify that Ball and its other student-athletes meet the requirements of eligibility. If UCLA knowingly certifies an ineligible student-athlete, the school could face NCAA sanctions.

As an added twist, Ball’s situation has a unique quality that may give him—and UCLA—sufficient cover. It’s plausible that Ball hasn’t signed any kind of contract with BBB and hasn’t been directly paid anything. It’s also plausible that Ball won’t receive some other form of compensation, such as a percentage of sales on MB1. Along those lines, Ball might argue that he is simply helping out his dad, just any like any son or daughter would do, and that any money that flows from MB1 goes to his parents, not to him. Since BBB is a privately held company, it could prove difficult for either UCLA or the NCAA to untangle the precise fiduciary relationship between the company, LaVar Ball and members of his family.

LaMelo Ball’s options

With his basketball development and NBA future foremost in mind, Ball has at least four options to resolve the potentially problematic relationship between his MB1 sneakers and the NCAA.

Option 1: Attend UCLA for eight months and bank on the NCAA looking the other way.

The most likely scenario for Ball is the same as the one before his sneaker deal: matriculate to UCLA, spend a semester and a half there and then declare for the 2020 NBA draft.

As explained above, Ball is armed with multiple arguments that his relationship to MB1 sneakers does not violate NCAA eligibility rules. While none of those arguments are “legal slam dunks”, each has a chance of working.

Ball also knows that the normally confident NCAA seems strangely meek when it comes to the Ball family. Consider the NCAA’s response to Lonzo Ball repeatedly wearing and promoting BBB apparel during his year at UCLA: crickets. While LaMelo’s situation is different from that of brother Lonzo, he may nonetheless feel emboldened by the NCAA’s silence.

The NBA's Seven Saddest Rebuilding Situations

Option 2: Skip UCLA. Spend the 2019-20 season abroad or in the G League.

While Ball won’t be eligible for the NBA draft until 2020, he can turn pro and earn a sizable salary playing basketball long before then. The NBA is unusual in featuring a 19-year-old age eligibility restriction that exceeds when a person is traditionally thought of as an adult—age 18. Many pro players in Europe and elsewhere are teenagers. Ball could join them, at any time. Two NBA players, Brandon Jennings and Emmanuel Mudiay, skipped college during what would have been their freshman year to play professionally abroad. Mudiay, who was selected 7th overall in the 2015 NBA Draft, reportedly earned $1.2 million to play for the Guangdong Southern Tigers during the 2014–15 season.

Would Ball consider playing in China or Europe for a year? Possibly. The money could be hard to pass up, especially if foreign teams view Ball as an American celebrity who would attract fans. For his part, LaVar Ball would presumably view his son playing abroad as an opportunity to expand the BBB brand into other markets.

Ball could also stick around the U.S. for his 2019–20 season and play in the G League, which welcomes players right out of high school. The drawback to the G League would be pay. Ball would not be eligible for a two-way, G League-NBA contract since he would not be eligible to play in the NBA. He would instead be relegated to the highest pay in the G League’s exceedingly modest pay scale. By rule, the “highest” allowable pay is currently about $26,000. While that amount would be higher in 2019, it would be a far cry from what Ball could earn abroad. Granted, Ball could supplement his G League pay with endorsement income, but he would still be passing up a great deal of money if he “turned pro” and didn’t do it outside the U.S.

Option 3: Sue the NCAA over its rules that deny him a chance to profit off of his name, image and likeness.

I would be very surprised if Ball filed a lawsuit against the NCAA in order to gain the right to play college basketball for one year. Given his other options, such an attempt would probably not be worth his time or energy. Then again, the Ball family is willing to take chances and it doesn’t shy away from controversy. Taking on the NCAA in court would fit that description.

So could Ball sue the NCAA and win? He would have a chance.

As a celebrity from a celebrity family, Ball finds himself in a unique position to argue that NCAA rules deny him the fruits of his name, image and likeness. Given Ball’s marketability, such a denial could cause him significant financial injury. In a lawsuit, Ball could assert that the NCAA and its member schools have joined hands in an anti-competitive arrangement to prevent him and other players from being able to license their identity rights or “brand.” Ball would contend that such an arrangement constitutes an unlawful conspiracy under federal antirust law.

The law might be on Ball’s side. If he sues the NCAA in federal court, the case would likely be litigated in a California federal court. California federal courts must follow case precedent issued by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In 2015, the Ninth Circuit upheld former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon’s antitrust victory against the NCAA (as a disclosure, I am collaborating with O’Bannon on his forthcoming book, “Court Justice”, to be published by Diversion Books in February 2018). O’Bannon successfully argued that the NCAA and its members violated antitrust law by using players names, images and likenesses in video games and other products without their consent. Ball could rely on O’Bannon’s victory as precedent and advance his own case against the NCAA.

Here's What Tom Brady texted Isaiah Thomas After the Trade to the Cavaliers

Option 4: Sue the NBA over the age eligibility rule.

If Ball might be willing to sue the NCAA in order to play a year of college basketball, perhaps he would also be willing to sue the NBA in order to enter the league at the same point of life as LeBron James, Kobe Bryant and Kevin Garnett experienced years ago. Like several other NBA stars, those players pursued the NBA right after high school graduation. Until the NBA and National Basketball Players’ Association collectively bargained the 19-year-old age rule in 2005, players could make that “prep-to-pro” jump.

Ball would have his work cut out for him if he sought to take on the NBA’s age limit, which, as mentioned above, is found in Article X of the CBA. Because Article X was collectively bargained, it gains a significant degree of protection from antitrust law. Generally, if a rule is collectively bargained and if it primarily impacts players, it is exempt from antitrust law.

That said, there is a logical legal argument that the NBA’s eligibility rule doesn’t primarily impact NBA players. It instead primarily impacts those players who are not yet in the NBA by virtue of a rule that denies them access to the NBA. This argument was used in Maurice Clarett’s 2004 case against the NFL over its age limit. Clarett’s case was argued in the U.S. Court of Appeals or the Second Circuit (as a disclosure, I was a member of Clarett’s legal team). It failed there, but this line of legal reasoning might enjoy more success in labor-friendly jurisdictions. One such jurisdiction happens to be the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which governs the California federal courts that would hear Ball’s case.

To be clear, the most likely scenario for Ball is the traditional one: he enters UCLA, plays for eight months and is drafted by an NBA team three months later. But the Balls are anything but traditional. We’ll see how it all plays out.

Michael McCann, SI's legal analyst, provides legal and business analysis for The Crossover. He is also the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of New Hampshire School of Law.