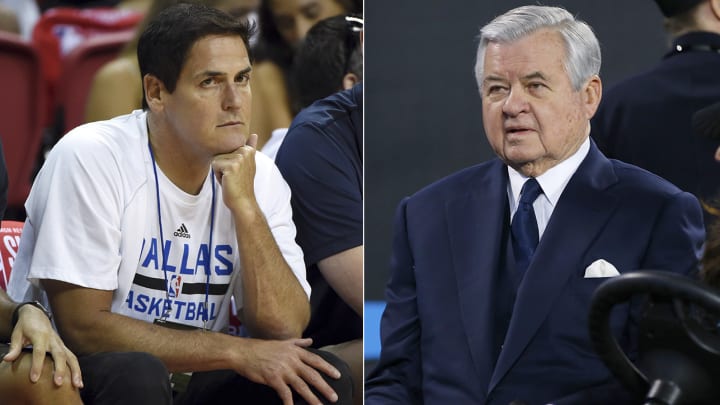

The Striking Contrast Between the Mavs and Panthers In Crisis

Mark Cuban is the archetype of the hands-on sports owner, yet claimed to have no knowledge of his organization’s corrosive culture, one that demeaned women and imperiled their safety. Terdema Ussery was the team’s longtime CEO, who claimed that he was unaware of any sexual harassment allegations against him, never mind that he was the subject of a widely-reported, multi-week investigation in 1998. Ussery was the same CEO, the man atop the org chart, who claimed that he had brought attention to colleagues’ workplace sexual improprieties, but “the organization” had refused to address his concerns.

But for all the ironies that wreathed around each other as SPORTS ILLUSTRATED reported on the misogynistic Dallas Mavericks office culture, this one was perhaps most striking: As “locker room atmosphere” has been colloquialized, the Mavs’ literal locker room was a safe space, accommodating and respectful to women. One female source told SI, “I always felt way more comfortable in the locker room than in the office. Dirk [Nowitzki]? Amazing. Shawn Marion? Amazing. Vince Carter? Always respectful. Coach [Rick] Carlisle? Never anything but businesslike and professional.”

This revealed itself last week as well. The Mavericks intersection with the #MeToo movement was the rare unseemly sports-and-misogyny story that had nothing to do with athletes. Yet there was Nowitzki on Wednesday, standing before bleachers, weighing in: “It's tough. It's very disappointing. It's heartbreaking. I'm glad it's all coming out. I was disgusted when I read the article, obviously, as everybody was....I was shocked by some of the stuff. Just really, really disappointed that in our franchise—my franchise—that stuff like that was going on. It's just very sad. And we as a franchise, we feel bad for the victims and for what happened to some of these ladies—like I said, truly, truly disgusting. Our thoughts and prayers are definitely with these victims."

It’s a pity that the Mavericks weren’t playing in Charlotte that night. If so, Panthers fans would have gotten a vivid comparison, a first-hand demonstration of just how shabbily their NFL team had treated the community in the aftermath of a recent similar crisis.

Two months ago, SI published its investigation of the Carolina Panthers, asserting that owner Jerry Richardson had harassed multiple female employees, used racial epithets and racially-tinged language with a scout, and then bought silence with restrictive NDA’s. There were distinctions, of course, between the Mavs and the Panthers. In the latter case, the owner wasn’t merely being accused of lacking institutional control; he was the accused bad actor. Still, the similarities were abundant—both stories of abrasive sports workplaces, powerful men creating a hostile environment for their less powerful female colleagues.

The biggest differences surfaced in the respective aftermaths. Compare Nowitzki’s response to that of his analog, Cam Newton, face of the Panthers’ franchise. Here was Newton in the days following the revelations: "When you hear a report about Mr. Richardson, a person that we all, as an organization, have so much respect for and the people who did come out saying certain things about racial slurs, sexual assault... it's still allegations.''

Never mind the absence of compassion. What about the sheer indifference, the lack of curiosity? With one phone call—or even a cursory glance at a media guide—Newton could easily have discerned the identity of the scout and ascertained for himself whether Richardson had, in fact, used racial epithets.

Following Nowitzki, Dallas coach Rick Carlisle addressed the allegations leveled against the Mavericks: “I’m grateful we live in a place and time where people have the courage to speak up about things like this. I also have a 13-year-old daughter and I want her to know that it’s both brave and safe to speak out….Things happen for a reason,” Carlisle said. “Any problem or crisis presents opportunity, and this is an opportunity for us to get something fixed.”

Contrast that with Panthers’ coach, Ron Rivera. In the Panthers’ next game after the story broke, Rivera gathered his team in the locker room before kickoff. “Everything we do is about team. The most important thing is about team, okay? All right, do me a favor—‘Mr. Richardson’ on three. 1-2-3!"

Exclusive: Inside the Corrosive Workplace Culture of the Dallas Mavericks

Pressed on why he would dedicate a game to a man accused of vile behavior, Rivera resorted to the time-honored logical fallacy that we can judge people only if we ourselves have been impacted. “What I’ve always said is I know nothing about that. I can only speak for what he has been to me and the players,” Rivera said. “And that’s why I did it.”

Then, compare, too, the owners themselves. Since the allegations against Richardson have surfaced, he has not made a public statement about them. Not one. No apologies to women or to the Africa-American scout he has aggrieved. No apologies to the city and community that gifted him $87.5 million in public money to fund renovations to his stadium. No remorseful admissions; no fiery denials. Just silence.

In Dallas, Mark Cuban knows as well as anyone that he has plenty to answer for. But retreating once allegations came to light wasn't an option. Within an hour of being asked for comment by SI, Cuban was on the phone for what was easily 20 minutes, proffering explanations and apologies. By that point, he had already fired his head of human resources, suspended a beat writer named in the story, and arranged for outside experts to provide sensitivity training to every Mavs employee, himself included.

Within hours of the story breaking, the NBA had issued a strongly-worded statement of condemnation. On Wednesday, the league announced an independent investigation of the Mavericks. (Unsolicited tip: examine the American Airlines Center workplace as well as the team itself.) By Thursday, NBA commissioner Adam Silver had sent letters to all 30 teams, announcing the creation of a confidential hotline, whereby any team or league employee “could report any concerns arising in the workplace, including but not limited to sexual harassment, illegality, or other misconduct.”

In Charlotte, when first apprised of the allegations the team announced an internal investigation led by a co-owner. (Aware of the bad optics, the NFL quickly took over and announced that an outsider, former SEC chair, Mary Jo White, would take over.) Given a chance to comment on dozens of assertions, the team took more than a day and then issued a boilerplate statement. Within hours of the story’s publication, Richardson, without referencing the allegations against him, announced that he was selling the team.

By accident or design, this marked a brilliant stroke of crisis management. The story pivoted away from the allegedly abhorrent conduct of a prominent owner toward women and minorities he had offended and then paid off. Instead, the focus—and most of the NFL damage control—revolved around whether Diddy could outbid Oprah or Steph Curry for ownership, how much money the franchise could fetch, and whether it might relocate.

One could argue that this contrast offers some broader insight into the current sportscape at large. As the NFL’s ratings and popularity ebbs and the NBA’s flows, we point to athlete safety and global reach and social media strategy as the factors. But maybe it redounds to something simpler. One leagues conducts itself with some empathy and humanity and spontaneity. The other defers to expedience. One crafts policy, the other stagecrafts. One league fumbles. The other acts. And it doesn’t need to wait to the count of three.

Jon Wertheim is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated and has been part of the full-time SI writing staff since 1997, largely focusing on the tennis beat, sports business and social issues, and enterprise journalism. In addition to his work at SI, he is a correspondent for “60 Minutes” and a commentator for The Tennis Channel. He has authored 11 books and has been honored with two Emmys, numerous writing and investigative journalism awards, and the Eugene Scott Award from the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Wertheim is a longtime member of the New York Bar Association (retired), the International Tennis Writers Association and the Writers Guild of America. He has a bachelor’s in history from Yale University and received a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He resides in New York City and Paris with his wife, who is a divorce mediator and adjunct law professor. They have two children.