There's Never a Bad Time With Deandre Ayton

Watch SI TV’s behind-the-scenes feature on Deandre Ayton, where the big man discusses the criticism he faced at Arizona and the chip he carries on his shoulder heading into the NBA. Start your free trial of SI TV today.

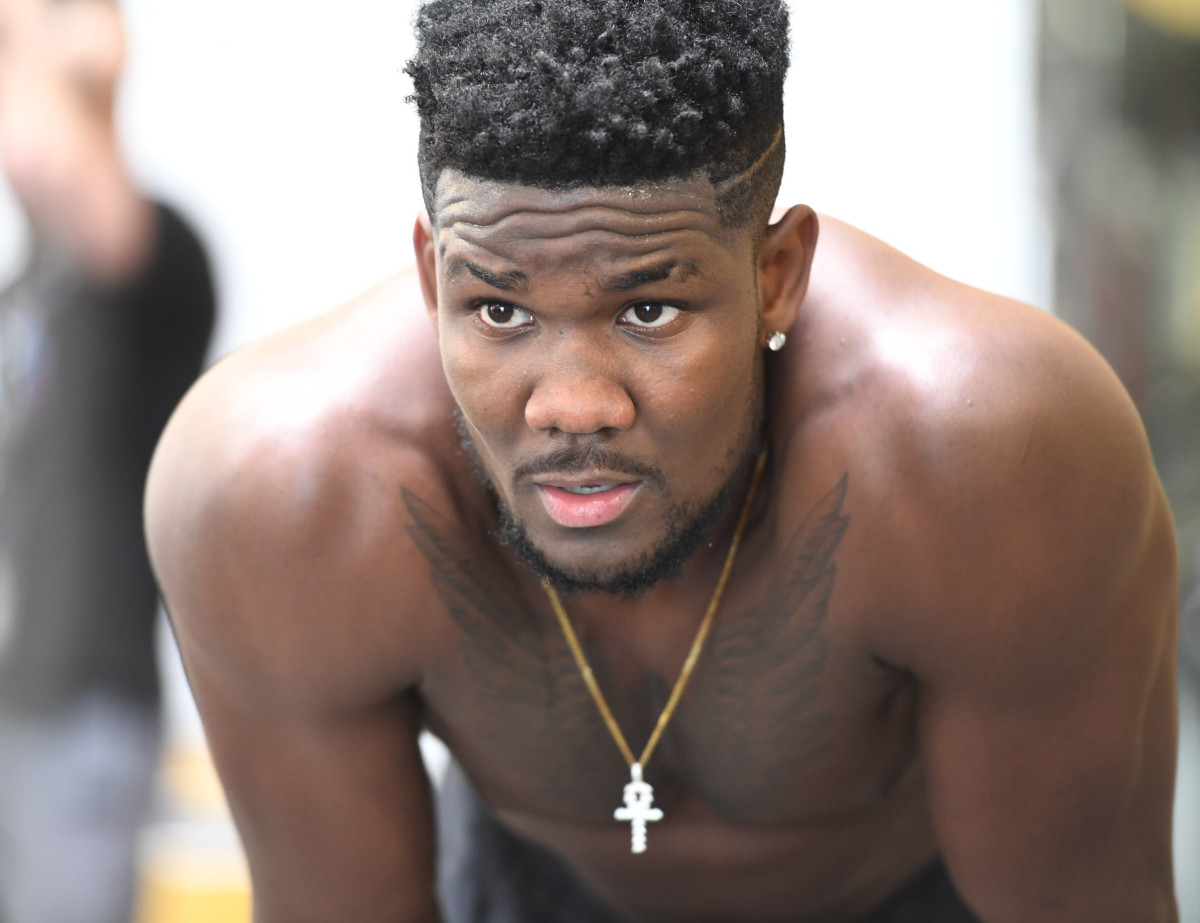

If a team of basketball scientists were asked to build the perfect big man in a laboratory, the finished product would look a lot like Deandre Ayton. The problem, on a Wednesday night in the middle of May, is that the 7'1", 250-pound Ayton is nowhere near a basketball hoop.

We're at a Topgolf franchise in Scottsdale, Arizona. Ayton has already sprayed ground balls all over the range, but he refuses to give up. He just watched his 41-year-old trainer, Rasheed Hazzard, swing calmly, almost in slow motion, and loft several beautiful iron shots. Clearly someone can play this game. "But you got the old-man swing," Ayton tells him. "No swag."

So standing in the corner stall on the lower level, Ayton licks his index finger and whirls it around his head. "Always check the wind," the 19-year-old says. Then he begins his backswing, contorting his 7'5" wingspan around a driver that's at least six inches too short, annnnnd ... another shank. The world's biggest beginner golfer cackles with delight.

This is part of the Deandre Ayton experience. His teammate at Arizona, Rawle Alkins, says, "When the situation is down or quiet, he'll loosen everyone up. Laugh, crack jokes. There's never a bad time with him." Former Wildcats assistant Lorenzo Romar predicts that one day Ayton will be on Inside the NBA. His mom, Andrea, calls him both a comedian and an entertainer.

After another round of scuffs and slices, Ayton finally turns to the group of friends behind him, looks around at the corner stall and shakes his head. "It's a weird angle," he decides.

We're hitting balls just 24 hours after the NBA Lottery in Chicago, where the Suns landed the top pick. That means there's a good chance that Ayton will stay in Arizona after a high school career that finished in Scottsdale and his single season of college basketball in Tucson. Sitting on a couch while the rest of the group takes turns teeing off, Ayton passes over a phone full of notifications from Phoenix fans thrilled at the possibility of drafting him.

Ayton attended the lottery himself, and says that his visit to Chicago wasn't exactly fun—he was very busy—but that it couldn't have gone any better. His hometown team is choosing first, he aced his on-camera appearances and, in between, he mingled with everyone from fellow draft prospects to team executives to commissioner Adam Silver. "He was just telling me how great this league is," Ayton says of Silver. "And how, as much as everybody wants to win and be competitive, you'll never find a league so close. Everyone knows each other. Everyone works with each other off the court. And a lot of these dudes are signed to the same agencies too."

The most dramatic question before the June 21 draft will center on Ayton and 6'6" Slovenian guard Luka Doncic, his competition to be the No. 1 pick. And funny enough, they are, in fact, signed with the same agency, BDA Sports Management. The two prospects even share a publicist, Alyson, who has been a go-between since the draft process began. Doncic followed Ayton on Instagram hours after the lottery ended, then Ayton followed back, then each excitedly texted Alyson. The two teens have exchanged a few messages since, wishing each other good luck. "We're just respectful right now," Ayton says.

But for all the diplomacy and the jokes, Ayton is direct when it's time to talk about his place in the draft. "No one's built like me," he says. "I play 110% on both ends of the floor." And does he care where he's drafted? "Most definitely No. 1," he says. "Not changing my mind. I worked too hard for that. I worked my ass off."

There are a few different versions of Ayton, and which one you get depends on what you're talking about. If the topic is basketball, he says all the right things. If the topic is life off the court, he will crack jokes about himself and everyone around him. He becomes the guy who orders two desserts at lunch—a massive brownie sundae and something called a Snickers pie—and then refuses to share with his girlfriend, Anissa, for two reasons. First, because he's flirting with her, and also because it's making the whole table laugh. And then when Anissa successfully steals one of the desserts, he sprawls his massive frame across the table trying to steal it back.

As long as everyone else is having a good time, so is he. But if he's talking about the journey that brought him to where he is now, a more guarded side emerges.

2018 NBA Mock Draft 9.0: Trade Speculation Heats Up

Ayton was raised in the Bahamas until he was 12. He remains intensely proud of his homeland, and the people from there are proud of him too. Mychal Thompson, the Bahamian big man who was drafted No. 1 in 1978 and whose son Klay plays for the Warriors, says, "I watched every Arizona game I could this year. It's thrilling, man. I feel like I've got another son in the NBA."

It was everything after the Bahamas that made Ayton's story complicated. "Home," he says, "I was perfect. I was home. I don't even want to talk about AAU. AAU was a bunch of s---. When I stepped foot in the United States, my life became a job."

After landing on the radar of scouts at the 2011 Jeff Rodgers Camp in Nassau, Ayton was offered the chance to come to the U.S. by a couple of coaches. His mother and his stepfather, Alvin, decided that it was the right thing to do. Basketball aside, it was a chance at a free education. So he moved to San Diego as a 6'5" 12-year-old and joined the world of elite amateur basketball. Less than two years later he was 6'10", and a viral video christened him the best eighth-grade player in the country.

"It felt normal," Ayton says, "until I grew up and realized I never really had a childhood. It was just basketball and business. Never went to Disneyland or any of that. Kids used to tell me about it, and I'd have to lie and say, 'Yeah, I went.' But I never never knew any of that."

For the next few years Ayton lived with three different host families and spent most weekends traveling the grassroots hoops circuit. He's not in touch with anyone from that time in his life, in part because for most of that time, he'd lost touch with his real family. "There were a lot of issues going on," he says. "Sometimes I'd go a month without talking to my mother. You're [in the gym] going 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. It was like a job."

Of life with the host families, he says, "They did a good job taking care of me, but it just didn't feel right to me. Like I was comfortable, but it just felt weird. It was very awkward."

His mother Andrea moved to Phoenix when Deandre was 16, extricating her son from San Diego, and things began to normalize. Looking back now, Deandre says he had become entitled, a bully who was resentful of the people around him. "I was lucky," he says. "My mom came and knocked some sense into my head. Like, 'Yo—that's not gonna work.'"

For his junior and senior seasons, Ayton enrolled at Hillcrest Prep, an elite basketball academy in Scottsdale. He briefly crossed paths with Marvin Bagley, who was at the same school for three months before transferring and continuing on an amateur hoops journey of his own. Ayton stayed, and he thrived, earning All-America honors and finishing his high school career as a top–five recruit.

Most casual sports fans first learned Ayton's name during coverage of the FBI investigation that has rocked college basketball over the past nine months. On Feb. 23, ESPN alleged that Wildcats coach Sean Miller had been caught on tape by the FBI offering $100,000 to an employee of an agent for Ayton's services. And while ESPN's story has not held up—Ayton and his family have denied any involvement, the timeline has been debunked, and there have been no findings of wrongdoing—the allegation still stings. "The exposure I wanted in college wasn't the exposure I got," Ayton says. "Me and my family did not expect that. It was bad." (Miller has said he expects to be fully "vindicated.")

Alkins recalls that he and his teammates were playing NBA2K when alerts flashed across each player's phone telling them that Ayton had been implicated in the scandal. Ayton looked down in shock. A few minutes later managers knocked on the door and brought him to meet with coaches. Later, the team met as a group to try to process everything.

"We realized," Ayton says of that night with teammates, "Everyone is really out here to get Arizona. Like, what did we do? And everyone's calling your phone. You're trending. You see your highlights on TV under this scandal. It hurts."

The team was scheduled to play at Oregon the next day. Since none of the ESPN allegations had been confirmed by NCAA investigators, the school decided that Ayton would suit up—but Miller would not be on the sideline. "If he coached that game right after the news broke, he felt like the environment would've been just too crazy," says Alkins.

The environment at Oregon was plenty crazy anyway. "I came out there for warmups," Ayton remembers, "and I saw this little guy with this microphone. And I'm running and running [through the tunnel], doing my pregame workout, and he's like, 'Here he comes!' The whole gym booed me." He cups his hands around his mouth to imitate the fans. "Hun-dred thou-sand! Da-da-da-da-da. Hun-dred thous-and!" During the national anthem, Ayton looked around the stadium and saw a group of students dressed as FBI agents, eyes trained on him the entire time.

Ayton finished that game with 28 points and 18 rebounds, along with four blocks. He played 44 of 45 minutes, and while the Wildcats lost in overtime, Ayton says that those 48 hours, surrounded by headlines and chants and fake FBI agents, were the closest he's ever felt to his teammates. "We ended up losing," Alkins says, "but it wasn't one of those feelings where we were disappointed. We were just happy to play hard together. It was like a movie."

Romar, who replaced Miller and coached Ayton that night, says, "I've never been more impressed by a player that age on a basketball court. To have his name thrown around in regards to something he didn't do, it really shook him. It really shook him up. But to rally from that.... "

After the Oregon game, the team bounced back to secure the Pac-12 regular-season title and dominate the conference tournament. Ayton finished the season averaging 20.1 points and 11.6 rebounds. He was named Pac-12 player of the year. Arizona was upset in the first round of the NCAA tournament—"Buffalo had some dogs," Ayton says ruefully—but that final month of that season never became the disaster it could've been.

Back at lunch, Ayton is looking at his phone when he says to no one in particular, "You saw Michael Porter Jr. say he was the best player in the draft?" A few seconds later, Ayton looks up to the rest of the table and tilts his head. "What draft is he in?"

Ayton will likely go first on June 21. From a physical standpoint, he checks every box imaginable. He's nimble enough to guard on the perimeter, he's tall enough to meet anyone at the rim, and offensively he's got a combination of skill and power that leaves him looking something like a new-age David Robinson. Playing with professional guards in the wide-open space of the NBA, his game could become even more dangerous.

Ayton describes himself as a monster and a bully when he's on the court. He grew up loving Kevin Garnett. Watching Game 2 of the Rockets and Warriors in the Western Conference finals, the first player he notices is Draymond Green. "That dude can change the game," Ayton says. "That's a veteran you want to learn from. You want him to take you under his wing, and let you learn to be a dog. That dude is the Warriors. I mean obviously there's Curry and Durant, but it's Draymond who can get under your skin and change the momentum of the game. And guarding the team's biggest, best players as well."

Fran Fraschilla, an ESPN commentator and draft expert specializing in international hoops, says if he had to choose between Doncic and Ayton he'd be "flummoxed." He leans Ayton for now. He recalls a 25-point, 16-rebound performance in a win at Arizona State. "I've watched a lot of basketball over my 59 years," Fraschilla says. "He was breathtaking. There was one play—he blocked the shot at one end, his teammate came up with it and [Ayton] ran by me at courtside. It was like the Coors freight train. I almost got a frost on me."

And as one NBA scouting director says of Ayton's appeal at No. 1: "He almost unequivocally is going to have the most value of anyone you could pick there. In terms of initial performance, and trade [value]. The guy is probably gonna be 20-and-10 as a rookie. He's just a physical monster. He's big, he's long, he's athletic. He can score around the basket, he can make a jumpshot. He's gonna be Rookie of the Year. There's a lot of positives there."

If there's any room for skepticism, it usually starts in one of two places. First, there's Ayton's ability to protect the rim and anchor a defense. He blocked 2.3 shots per 40 minutes—fewer than any of the past three big men taken No. 1 (Karl-Anthony Towns, Anthony Davis, Greg Oden). Because of that, some advanced metrics put his D on par with the likes of Jahlil Okafor's. Arizona did, however, have an incumbent center in Dusan Ristic, so Ayton played out of position and spent long stretches guarding the perimeter. That may have skewed his block numbers.

"There's some truth to that," says the same scout, when asked about whether the awkward fit at Arizona made his defense look worse. "But he's only going to see more skilled perimeter players and more shooting in the NBA. And he's just not a very alert help defender. How many years, and how much coaching, is it going to take before he's able to bring a level of focus and commitment on the defensive end that translates to winning?"

The second question is more abstract. In a league increasingly dominated by small ball and versatile wings, why should a team use the No. 1 pick pick on a big man? Jazz 7-footer Rudy Gobert was nearly played off the court by the Rockets in the playoffs, and Houston center Clint Capela's value was cut in half against the Warriors. Defensive metrics aside, Ayton is more athletic than a player like Okafor ever was and he's quicker laterally than someone like Towns. But at some point, the reality of the modern NBA makes life difficult for any big man.

Kevin Durant and the Dagger That Foreshadowed the Broom

For his part, Ayton is not worried: "Smallball? What is smallball? I play basketball. I play center, and if you haven't watched me play, I'm not a regular big man. I can move my feet. Not saying I can stop anyone out there who's in front of me, but trust me, I can really be a problem on the perimeter guarding somebody. I can switch from the center to the guards. The game is evolving. You got dudes like Joel Embiid, Anthony Davis, all these 7-footers, doing everything. They're unstoppable. We can grab the board, take it down the floor and then score just as well. There's no stopping us."

Those All-NBA comparisons may seem crazy, and how fans feel about Ayton's future might depend on which Arizona games they saw this year. But in any case, that is the curve—Embiid, Davis, Towns—that Ayton will be graded on. He is clearly good, but given where the rest of the sport is going, he'll have to be closer to great to justify a winning team's investment in a franchise big man.

There's no question that Ayton comes to the NBA with almost every tool you could ask for. And he has a history of improving. Romar notes that the 19 year-old hadn't lifted weights before college. "Within two weeks you could see a change," his coach says. Alkins echoes the point: "He can get quicker. And I wouldn't be surprised if he starts coming off screens, pick-and-roll. That's something to think about. Whoever's training him, if they get his handle right, he can play like a guard."

Off the court, as he's said, Ayton was forced to grow up faster than almost all of his peers. But there are still times when it's clear he's 19 years old. And it's in the moments where he strains to sound like a hardened, serious adult that his youth becomes most apparent.

The day after the golf outing, a minor social media controversy flares up. A website that specializes in search-engine optimization publishes a guide to Deandre Ayton, and the introduction fuses two unrelated quotes in a way that suggests he hated his childhood on the Bahamas. Eventually, that new, context-free quote makes its way to the people of the island nation.

"I saw that," Mychal Thompson says later. "He knows what's in his heart. Everybody who knows him knows how proud he is of his country. Anybody who tried to frame it that way is just trying to bring him down."

All day in Phoenix, though, Ayton hears from people back home. On Twitter, Instagram, text messages. He's stressed. He huddles with his publicist and issues a statement on social media: "It's upsetting to see how my words are being used in the media today. I love the Bahamas. That's my heart! I have never said one disparaging thing about the place that continues to give me and my family nothing but love and support.”

The whole episode reopens old wounds, and his guard comes up again. At lunch Ayton is talking about the nature of the media, using his Instagram following as an example. "I had 30K," he says, and after the ESPN report, "I gained 60K in one night. The whole world knew me as the college athlete that took [money]. That's how this world works. They love negativity.

"In college I really couldn't say nothing. Coach Miller was like, 'Keep a low profile. Don't worry about that stuff.' But now? Oh, yeah. Wait till I start really getting some money in my pocket. I'll say a few things. Pay that fine."

But then he breaks character—"No, I'm playing"—and a few minutes later he's promising the rest of the table that he can sing. He tells a story about the Bahamas. He was in church performing a solo next to his sister when he spotted a friend in the back—"I was tall, so I could see the whole audience"—and burst out laughing in front of the entire congregation. "My mom gave me the whooping of a lifetime," he recalls. "That was the end of my singing career. But I can sing."

So, obviously, someone challenges him to sing on the spot. He refuses. What about the national anthem next year? "Chill, chill, chill," he says. "I'm not Victor Oladipo."

Singing anthems or not, Ayton the player will be fine for the next decade. The hope for Ayton the person is that the NBA will allow him to be himself and enjoy this. He is the rare 19-year-old for whom life as a professional athlete might actually be easier. The next level will come without AAU tournaments and host families. There will be no NCAA investigations, better entry passes, and more floor spacing than ever.

For now, there's just basketball and workouts. And at the end of lunch, after the Snickers pie and the brownie sundae, neither of which Ayton came close to finishing, Hazzard slides over a scouting report from his time as an assistant with the Knicks. Ayton's eyes get big as he thumbs through several pages of stats and plays. "This is like an exam," he says.

His trainer tells him that an NBA scouting report will have all the information he needs. "You may have three pages of diagrams," Hazzard says. "All the different calls, the variations of what they run, and the pick-and-roll coverages you'll use. And like you said about an exam? The exam is the game."

"This is the cheat sheet," Ayton says.

"Exactly," Hazzard nods.

"And at the end of the day," his trainer adds, "if you forget the coverage, just be athletic and big, and go block some s---. It's still a simple game."