What One Milwaukee Police Officer's Firing Could Mean to Sterling Brown's Lawsuit

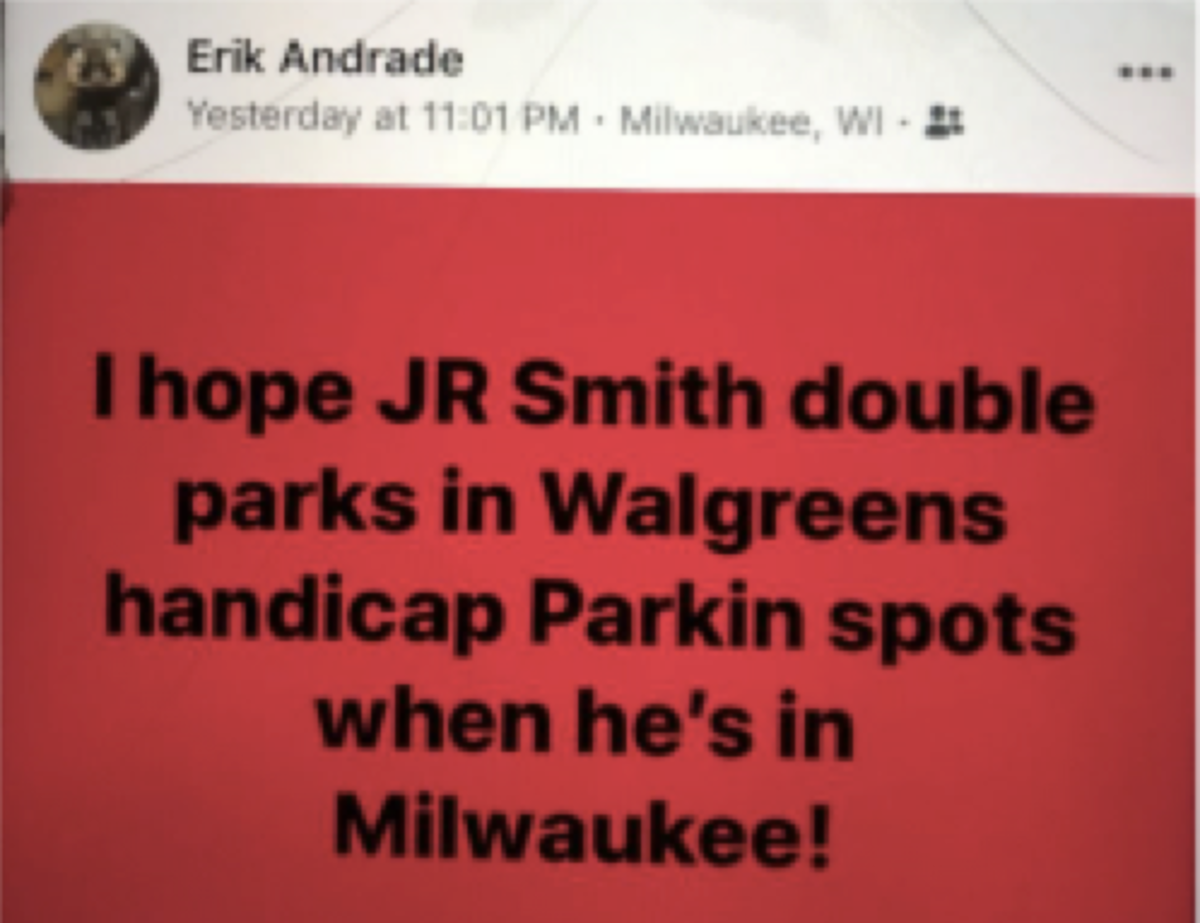

One of the Milwaukee police officers who was present during the controversial arrest of Bucks guard Sterling Brown outside of a Walgreens in January has been fired on account of what Milwaukee police chief Alfonso Morales describes as “racist”, “derogatory” and “mocking” social media postings. Those postings were made by officer Erik Andrade, who ridiculed Brown in overtly racist and personalized ways.

In a statement, Morales expressed that while Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) officers are “free to express themselves as private citizens” and as consistent with the First Amendment, officers’ speech pursuant to their official duties and professional responsibilities is not accorded the same degree of protection under department policies. Morales described Andrade’s postings as “directly affect[ing] his credibility to testify in future hearings as a member of this Department.”

Brown’s encounter with Andrade and other officers

Andrade was one of eight officers on the scene when the 23-year-old Brown was taken to the ground, electrocuted and kneeled in the groin due to a parking violation. As detailed more fully in an earlier SI story, Brown had parked his loaner Mercedes-Benz across two handicap spaces in a mostly empty Walgreens parking lot one frigid early morning in January. Brown had clearly broken the law, but his offense was not a crime. Instead, it was a parking violation punishable by a $200 ticket and, sometimes, a car tow.

Brown received a ticket but also far more extensive—and physical—types of punishment.

To that end, as Brown returned to his car, he was stopped by Milwaukee police officer Robert Grams. As revealed by Grams’s Body Worn Video Camera, the encounter with Brown soon turned hostile. Grams is accused of yelling at Brown to back away from his vehicle, warning Brown that “I’ll do what I want, alright, I own this right here.” That remark prompted Brown to reply, “You don’t own me.” Grams also allegedly shoved Brown.

Grams called for backup and within minutes a total of eight officers were on the scene of a traffic violation. They noticed that in the backseat of Brown’s car were paper targets that had bullet holes in them. The officers also saw a small object in Brown’s pocket, which minutes earlier Brown had revealed was a key fob. Indeed, the officers witnessed Brown reach into his pocket to use the key fob to deactivate his car alarm. Further, Brown was unarmed. He assured the officers that he had no gun or any weapon.

Unpersuaded, one officer pulled out a pistol, another grabbed Brown’s left arm and still another kneeled Brown in the groin. Several officers then threw Brown to the pavement. While Brown was pinned on the ground, one officer directed another to use a Taser on the 6’6", 225-pound Brown. Brown was then repeatedly electrocuted in the back while he screamed in pain. Grams then allegedly stood on Brown’s legs while telling another officer that if Brown “hadn’t been such a dick” none of this would have happened. Grams then allegedly said, “What is wrong with these people, man?”

Brown remained face-first on the wet concrete for several minutes before being handcuffed, placed in a cruiser and driven to a local hospital for treatment of facial lacerations and two puncture wounds in the mid-back. Here are images of his injuries:

Later that morning, Brown was brought to Milwaukee County Jail. Brown’s attorneys, Mark Thomsen and Scott Thompson, contend that their client was questioned prior to receiving his Miranda warning against compulsory self-incrimination. Brown’s car was also searched without a warrant or (allegedly) probable cause. Brown would be released without a charge.

Andrade authors racist social media posts

During or shortly after Brown’s detainment, Andrade used social media to mock and embarrass Brown. In this Facebook post he ridicules his first encounter with Brown:

Andrade continued to post degrading statements, memes and photos about Brown and other NBA players and African-Americans over the next several months—all without his superiors taking steps to stop Andrade. Consider these:

Impact of Andrade firing’s on Brown’s lawsuit

In June, Brown sued the city, the police department, Morales and the eight officers for several claims, including: deprivation of his civil rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Brown asserts the officers treated him differently—and worse—because of his race); excessive force (Brown highlights the seemingly unwarranted use of a Taser and the application of blunt physical force despite him appearing to be calm and cooperative and despite his underlying offense merely being a parking violation); violation of Brown’s Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures (Brown contends that officers lacked probable cause when they detained and placed him into custody and when they searched his car without his consent); and a so-called “Monnell Claim” which addresses the failure of a police department to adequately train and monitor its officers (Brown argues that the MPD has turned a blind eye to some of its officers allegedly using multiple sets of law enforcement policies—one that applies to white people and one that applies to persons of color—and that his encounter is illustrative of this system-wide problem).

Judge Pamela Pepper of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin is presiding over Brown’s case. SI has obtained court pleadings, including the defendants’ recent answer to Brown’s complaint. As expected, the eight officers assert that they are immune from liability under the doctrine of qualified immunity. This doctrine dictates that private citizens can’t sue the government and certain persons who work for the government unless the government agrees to be sued.

There are many exceptions to qualified immunity, but the defendants insist that none is present here. To that point, the defendants assert the officers “acted in good faith, without malice or intent to harm, and their conduct did not violate a clearly established constitutional law or statutory right which a reasonable person would have known.” The city and MPD also note they may be protected by immunity.

Assessing the Details of Jabari Bird's Domestic Violence Arrest

Obviously, Brown and his attorneys believe that the officers acted in bad faith, with malice and in violation of clearly established constitutional law and statutory rights. In addition, the MPD itself has found that these officers failed to comply with their core duties. In May, Morales suspended Sergeant Sean Mahnke (the officer who allegedly asked that Brown be electrocuted by a Taser) on account of a “failure to take control of the situation within his supervisory capacity.” The other officers were either suspended or required to attend remedial training.

The firing of Andrade is also relevant to Brown’s case. Andrade was fired for making racist social media posts, including about Brown, over a period of months. Brown can attempt to argue that Andrade’s firing proves that he was inadequately trained and supervised by MPD. After all, had Brown been properly trained and supervised, he either would not have made those posts or would have been fired months ago. Along those lines, the fact that Andrade made a number of posts indicates that his misconduct was not an isolated mistake. Instead, it reflected a pattern of transgressions apparently acquiesced to by his superiors at the MPD.

The defendants might argue that Andrade’s firing should be classified as a “subsequent remedial measure,” which under the federal rules of evidence refers to corrective actions taken by the defendant that would have made an earlier harm less likely to occur. In many instances subsequent remedial measures are inadmissible in a trial on the logic that defendants should be encouraged, not deterred, from repairing hazards. If plaintiffs in a trial could refer to defendants’ subsequent repairs to prove the defendants were negligent, the defendants would be less inclined to undertake those repairs. Expect the two sides to debate the impact of Andrade’s firing on Brown’s claims and its relationship to admissible and inadmissible evidence.

In addition, the defendants maintain that the injuries sustained by Brown “were caused in whole or in part by his own acts or omissions or his failure to mitigate or the acts and omission of persons other than these answering defendants.” Brown is poised to argue that such a depiction is not only offensive but outright wrong. Brown contends, and video evidence seems to support, that he cooperated with officers’ instructions and avoided making any hostile statements. MPD officers will need to provide believable testimony about their encounter with Brown that would help to lawfully justify their actions and motivations.

The Crossover will keep you posted on the Sterling Brown litigation, which could end in a settlement long before a trial.

Michael McCann is SI’s legal analyst. He is also Associate Dean of the University of New Hampshire School of Law and editor and co-author of The Oxford Handbook of American Sports Law and Court Justice: The Inside Story of My Battle Against the NCAA.