Doc Rivers Q&A: Clippers Coach Speaks on Sacrifice and the Value of Giving Back

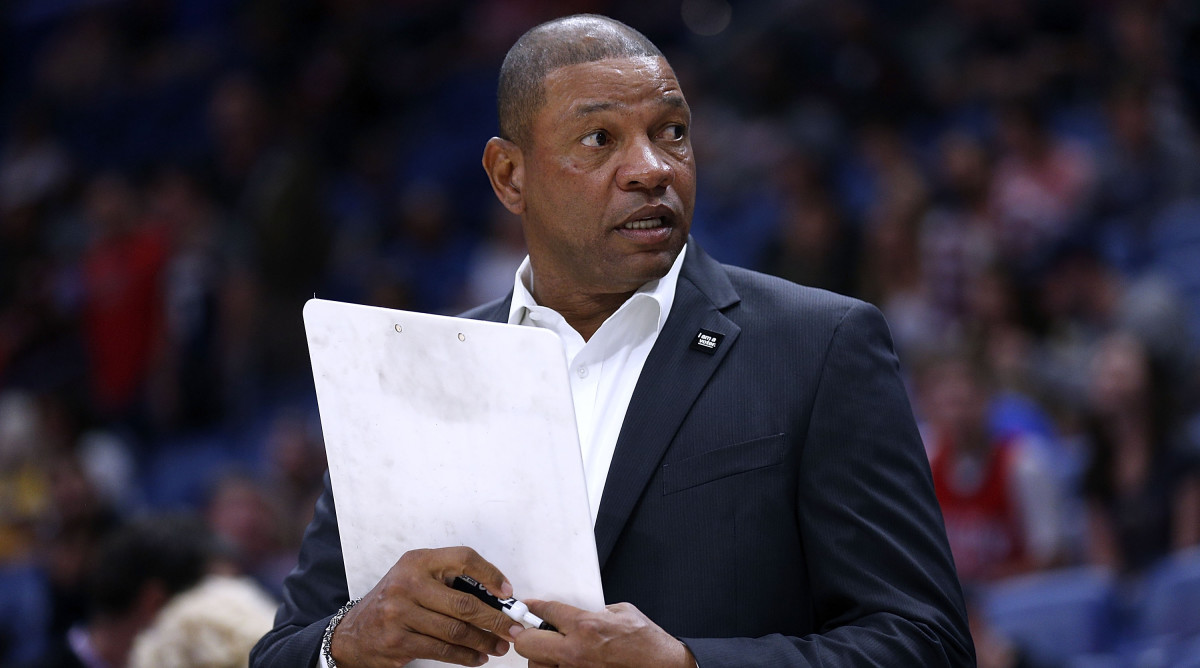

Glenn “Doc” Rivers is the head coach of the Los Angeles Clippers but is best known for his work guiding the Boston Celtics to an NBA championship in 2008.

Behind the scenes, Rivers’s humanitarian work with Boston’s ABCD anti-poverty group over the past decade has played a tremendous role in the group’s ability to impact the city’s youth and support families in need.

And while Rivers coached his Clippers to a 133–113 win over the Rockets in Houston on Friday, there was also a ceremony in honor of his ongoing charitable contributions to the city of Boston and beyond. Rivers’s induction into the ABCD Hall of Fame echoes his playing career, as he was always willing to sacrifice for the good of the team.

Rivers spoke with Sports Illustrated about his work with ABCD, in-depth memories of the 2010 Finals loss to the Lakers, his displeasure with President Donald Trump, and more.

Justin Barrasso: Your humanitarian work goes largely unnoticed because you never brag or boast about your contributions to youth groups around the country. Why is it so vital for you to give back?

Doc Rivers: Sports are a vehicle to do a lot of good. Not every athlete needs to speak out, but you should if you want to. People are going to support you no matter what, and there are people who are going to dislike you no matter what. All you can do is to do your best and live your best life. If we all do that, then we’ve got a chance. For me, I can live my best life by helping others live theirs, too. You can’t just take from the bank. You need to make deposits, too.

JB: You have devoted much of your life to basketball, but you have also always wanted to give back to society in a meaningful manner. Is there any connective tissue between humanity and basketball?

DR: I tell every team I coach that we need to make sacrifices. In basketball terms, if every player stayed in their comfort zone, then we would never win. Players need to open up their hearts and get out of their comfort zone, and then they’ll win.

I told every player on my 2008 Celtics team to take a deep look at themself. I had them picture themself as a 20-year-old ready to open up and tell someone that they love them. Now I explained that they would be scared to get their heart broken, but if they didn’t share how they felt, they’d never get the person they love. That’s the same thing to me as getting a title, you need to come together as a team.

That is the same thing people need to do, sacrifice and work together. If you’re to willing to say ‘I love you’, and you’re willing to get your heart broken, then you are willing to win.

JB: That story is incredible. Do you recall when you had that ‘08 team, which went on to defeat Phil Jackson’s Lakers in the NBA Finals, tell each other that they loved one another?

DR: That happened early on, during the preseason in Rome. I remember Kevin Garnett telling me, ‘I love you, man.’ I laugh about it now, but he meant it.

JB: How did the manner in which you were raised develop the way you see the world?

DR: I was taught by my parents to view people as people. I grew up in Chicago in the 1960’s, which was on CBS every morning with race riots. Blacks and whites were separated. But my parents never let me become bitter. Bitterness solves nothing.

I look at Donald Trump right now, and I can’t stand 99.9% of what comes out of his mouth. I think he’s been the worst person that I can remember for race relations. Having said that, attacking him does nothing. That only gives his base a stronger position. The answer is rallying to vote and trying to create change. I think what LeBron James has done is special—he’s not talking about Trump, he’s doing good things. When you don’t like something, you get involved and you fight. More people will go to the next Drake concert than will vote, but when you want to create change, you should stand in line to vote. And volunteer.

JB: You wanted to contribute to society, which is why you have dedicated time and money into the ABCD organization in Boston. What about that group is so meaningful to you?

DR: The way they help the youth, especially during the summer. It’s been proven that inner-city kids lose what they’ve learned from school over the summer because they don’t have enough programs to help continue their education. When you’re wealthy, you have more opportunities for education over the summer. Those inner-cities kids fall behind. There needs to be an anti-poverty group, and that’s what ABCD is. They are not anti-white or anti-black, or against a political party, they are all about helping people learn to fight off poverty. They’re not just handing things out, they are teaching people how not to be poor. That is an incredible group.

JB: Fact or fiction: your introduction to ABCD took place over your morning coffee during your first season in Boston?

DR: I was by myself, drinking my coffee one morning, my family was back home in Orlando. I read about ABCD in the paper. I don’t read the sports, I’ve never read the sports section. That’s a bad idea, not because there is anything bad or good, but for me, it allows me to do my job and focus. I’m never swayed just because of a story. Also, it allows you to never be bitter. You just do the best you can do.

So I was sitting at home reading the newspaper, which I still love to do. And I saw this article about ABCD, which I thought was this cool group. The part that caught me was that they didn’t focus on just one charitable cause. Over time, I’ve seen it all, especially the work they do with young people. So the story immediately caught my attention.

The next morning, I went to practice and brought the paper with me. I asked my assistant Annemarie [Loflin] to reach out to the organization. I had no idea how they could use me, but I knew I wanted to be involved. That’s how it started.

NBA POWER RANKINGS: The Cavaliers Continue to Sink Without LeBron

JB: Ray Allen had no problem knocking down threes with the Celtics, but it helped when he had Tony Allen setting screens for him. You bring a bright spotlight to ABCD, but the group would not be where it is without the work of ABCD’s Bob Elias.

DR: Bob Elias is an angel. Fiscally, he could be so much more successful, but he wants to give. He sets the screen then he gets out of the way. He does all this work and rallies up all these people for ABCD, then he disappears. Bob is one of those guys who must go home and sleep with a smile. He does all this work and gets no credit, but I bet he sleeps well at night knowing all the things he does.

JB: ABCD reminds me in some ways of old-school law enforcement, back when people would go to police officers with civil questions. Your father operated in that manner as a police lieutenant—he knew the neighborhood and helped local families. Do you see a connection between your father’s work and the ABCD cause?

DR: Very much so, that is true. My father was actually sick at the time I reached out to ABCD.

JB: You lost your father early into the 2007–08 season. That team went on to win an NBA championship, but a tight bond was built in November of that season when Kevin Garnett dedicated a win to the Rivers family after your father passed away.

DR: That was a really emotional time for all of us. I’d never been away from the team. They’d seen me get upset and emotional in speeches, but nothing like that. They saw that, a different side of me, and all those guys—Kevin, Paul, Ray, Rondo, Perk, everyone—cared. They didn’t need to care, but they did.

Listen, we won a title. But if we hadn’t, that was still the closest group of guys I’ve ever coached, and the most functional group. That group didn’t always get along, but when the buzzer went off, that team was tight. I’ve never been with a group that was so able to set anything aside and make the other team their opponent. That was an incredible group.

JB: Back when you played for the Spurs, a group of arsonists burned down your house in 1997 in what appeared to be a racially-motivated crime. I remember you talking even back then about the need for kindness and humanity.

DR: That’s one of the reasons I admire ABCD. Even when I left Boston for Los Angeles, I didn’t think the right thing, or the human thing, to do was just leave. So I called Bob Elias and said, ‘I’m not leaving ABCD.’

I didn’t join ABCD because I was the coach of the Celtics. I didn’t join ABCD because I was living in Boston. I joined ABCD because it’s a great group, and whether I was living in Boston or not, I wanted to stay involved. For me, it’s not about where I live, it’s about how special the group is.

JB: In addition to ABCD, there is still a strong relationship between yourself and the city of Boston. What makes that connection still resonate today?

DR: It’s the only town that I’ve played in or coached in where people ask about my wife and kids. It’s amazing how much the people of Boston still care about me. It’s different here, it’s a family. People here invest in you completely, and that hasn’t gone unnoticed.

Even when I first got here and our record struggled, people still cared about me. It’s funny, because when I first took the job, a ton of people told me not to come to Boston. All I heard was, ‘It’s a tough town, the fans are brutal.’ And all I could think was, ‘These people care!’ They’re engaged. That’s a good thing.

On our worst day, even when Danny [Ainge] and I were being booed at times, I never viewed that as a bad thing. I thought, ‘Well sh--, they care.’ I would rather have that than no one coming to the game.

JB: Speaking of humanity, the Celtics franchise has had an incredible run with race relations. The team hired the legendary Bill Russell as the first African-American coach, drafted the first African-American player in Chuck Cooper, and even started the league’s first African-American starting five.

DR: The Celtics only see green. And I’m not referring to money, I mean Celtic Green. The Celtics don’t get enough credit for that, and I don’t think Red Auerbach got enough credit for that. This whole Celtics legacy was created by Red. He had the ability to see players. If they were Celtics, he didn’t care about any other thing.

GOLLIVER: The Reeling Wizards Are in Need of a Major Shakeup

JB: Over the summer, the Clippers traded your son, Austin Rivers, to the Washington Wizards. Was it difficult to coach your son in the NBA?

DR: Coaching against him is strange, I’ll say that. Austin is an extremely competitive kid, which probably gets him in trouble sometimes. I remember when I first coached against him, he begrudgingly came over to me before the game for a hug, then he wanted to beat my butt.

I never envisioned coaching my son in the NBA, but it taught me a lot. He told me once, ‘You’re always harder on me.’ And I thought that was probably true. But I asked him for something good I do for him, and he said, ‘I know, whenever you’re hard on me, that you’ve got my back. There is no way you’ll try to screw me.’ Players believe that sometimes, even though it’s not true. So that made me realize, in order to be really good at what I do, I need to get to the point where every player knows I have their back. Then they’ll play free and be willing to sacrifice.

The toughest thing in the world was to see him traded. I was talking to [Timberwolves coach Tom] Thibodeau the day that the trade went down. Thibs reads every basketball book that’s ever made, and I asked if there was anything about trading your son in any of those coaching books. Thibs said, 'I’ll look,’ which was a classic Thibs answer and made me laugh.

JB: You are still strongly connected to the Celtics. Two pivotal games from your tenure in Boston that are still discussed are the championship win in Game 6 in 2008 and the devastating Game 7 loss to the Lakers in 2010. Do you still discuss those?

DR: I still think about the losses more than the wins. I always will. That Game 7 was on the other day, by the way. I’m not sure the last time I sat and watched it like I did the other night. It’s a brutal game to watch.

JB: Celtics fans do not need to be reminded that Kobe Bryant shot poorly that night, finishing 6-of-24 from the field.

DR: We went into that game thinking Kobe was going to shoot a lot, so we planned on double-teaming him more. The stakes were so high, he would trust less. And we were right. It took Artest making a big three and Fisher making a big three, which I’m still mad about. We were there to defend it, we just didn’t close out all the way.

Game 3 bothers me, too. Fisher played well there. But Game 7 still bothers me more. There was no Perk, Rasheed got gassed. People forget Paul’s arm went numb, we sat Paul and Kevin, which was the stretch where they made that run. It’s just little things. And I still look at what we could have done better. As the coach, you live with that. Even when you win, you’re still thinking about the things you could have done better as a team.

It’s funny. As a player, you just want to get better. As a coach, you always look at what you can do better.

NADKARNI: Stephen Curry and the Warriors Are Having Fun Again

JB: If you could make one change from that Game 7 in 2010, what would it be?

DR: I would have posted Kevin more. Even though he was struggling health-wise, even though, who knows, he could have got hurt, but I thought we could have posted him more.

If we could have done one thing over again, we wouldn’t have made all the changes. We were just taking away from our team, letting James Posey go, then letting Eddie House go. You can see the difference now. Danny knows he needs to keep his core together. Look at Golden State—their core guys have not changed. It’s pretty smart. Though they did also add Kevin Durant, which was pretty smart.

JB: The heartbreak of that loss was felt by Celtics fans. In a manner unique to sports, it helped further cement the relationship between the city and the team.

DR: Our highest moment was in 2008, but our lowest was in 2010. That was a very, very, very emotional moment. I knew that team wouldn’t be the same the next year. Kevin was never the same when he got hurt in 2009. Kevin’s leg was still dragging when he was running the fast break in the 2010 Finals. He was still really good, so you didn’t notice it as much. He’s the best, he really is.

JB: With all of the rule changes, would that 2008 team still compete with the competition right now in the NBA?

DR: Of course it does. We had a lot of shooting, a lot of role players.

BALLARD: David Stern Is Busy Crafting a Second Act

JB: Do the 2008 Celtics beat the 2018 Warriors?

DR: I would love to think so, and I would love to have the game.

JB: Who on that Warriors team guards Kevin Garnett?

DR: Who guards Paul Pierce? But they have guys that are hard to guard, too. It would be an interesting series. We were deeper. We had Posey, Tony Allen, Baby, Sam Cassell, Eddie House, Leon Powe, P.J. Brown. Everybody knows about how Danny got the main talent, but I thought everybody missed out on how Danny got those role players.

I remember the Eddie House decision. We were sitting around going back-and-forth, and Danny asked a simple question. He said, ‘Does Eddie House scare you when he comes in the game as an opponent?’ And I said, ‘He scares the sh-- out of me.’ So Danny said, ‘Let’s get him.’

JB: For those also interested in supporting ABCD, what is the best way to get involved?

DR: Call. Call the number, go to the website. That’s what I did. I called as a citizen looking to get involved. And I’ll make a bet with people—if you get involved, like I did 10 years ago, you’ll still be involved 10 years from now.

Justin Barrasso can be reached at JBarrasso@gmail.com. Follow him on Twitter @JustinBarrasso.