Garrett Temple Plays His Role in Historic Basketball Family

In the fall of 1971, on the sidewalk of “Free Speech Alley,” a 1,000-foot space in front of Louisiana State University’s student union, a future Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan began spewing hate and wouldn’t stop. After about the fifth “N----r” and “Jew,” a sociology classmate of David Duke’s got up to confront him.

Collis Temple, the first black man to integrate LSU’s men’s basketball team, began thoughtfully debating Duke, who eventually was shouted down. One man went on to become a prominent American racist, white nationalist politician, Holocaust denier, spewer of more hate. The other, Temple, used the game for greater good—education, unity, showing his children the miracle that happens when people of different colors work together.

“David Duke in his younger days had even stronger thoughts about segregation and a black man being on campus playing basketball then,” says Garrett Temple, Collis’s youngest son. “He was not afraid to speak his mind and speak eloquently in whatever he believed in. That’s my dad.”

In NBA parlance, Garrett Temple is referred to as "role player" or "journeyman," the reserve guard who would never be a star but always became that glue guy for every team, the respected veteran who played nails defense and could knock down the three on anybody. And that's why he has stuck around all this time—10-day contracts with five different teams over nine years, including his latest, the Los Angeles Clippers, who acquired him from Memphis at February’s trading deadline.

But the roles he would play and the journeys he would take often had so little do with basketball. Because if Garrett learned nothing else from Collis B. Temple, Jr., and Collis B. Temple, Sr., it's that he had a responsibility so much deeper than giving Mike Conley or Bradley Beal or De’Aaron Fox the rest they needed to be ready to finish by the fourth quarter.

Nearly a year ago, when an unarmed black man named Stephon Clark was shot eight times by Sacramento law-enforcement officers who mistook his phone for a gun, Temple attended protest rallies. He later helped organize a Kings’ public service announcement and tried to heal a broken community, listening to the police as much as the family wronged by them.

Just last week, when many of the league’s players were either taking off for NBA All-Star Weekend in Charlotte or a quick, getaway vacation during the break, Temple left the Clippers locker room and hopped aboard a redeye flight leaving LAX at 12:30 a.m. and touching down in Baton Rouge before 8 a.m.

He wanted to ensure he attended a board meeting for a charter school his family owns, a school for children who matriculate through public schools but often get left behind.

“How in the hell did you get here that quick?” Collis asked his son.

“I didn’t sleep, Pop,” he replied.

Collis shook his head, nodded.

“Now, for a young man to make that kind of commitment, to want to help, is really special. Garrett gets it. He’s always got it.”

He also didn’t have a choice.

Imagine your home state’s most prominent university rejecting your grandfather for their Masters program in 1955 because of his skin color. And the only way Collis B. Temple, Sr., got an advanced degree in agricultural economics was because of a Thurgood Marshall class-action suit against said schools. That school still doesn't admit your grandfather, because its president and faculty are scared to death what happens if they allow a learned black man on campus. But through a grant from the state legislature, they pay for him to attend Michigan State.

“They basically said, ‘Look, would you rather go to school or be in litigation for years to come?’” Collis Jr. recalls his father telling him. “My dad was like, ‘I’m just interested in going to get a Masters degree.’”

Collis Sr. becomes a school administrator, then a principal. He eventually meets and falls in love with a girl in the tiny Louisiana hamlet of Zwolle. Oh, that young woman? She was taught biology by George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute. That's Garrett’s grandmother, Shirley.

Fast-forward to 1969, and your father, the son of that couple, can play football and basketball. I mean, play. In fact, he just went to school with white kids for the first time when Louisiana integrated. Before Remember The Titans even happened, that young black man and Britney Spears' father—yes, Jamie Spears, the team's star quarterback—lead their mixed-race Baton Rouge football team to an undefeated season and a state title.

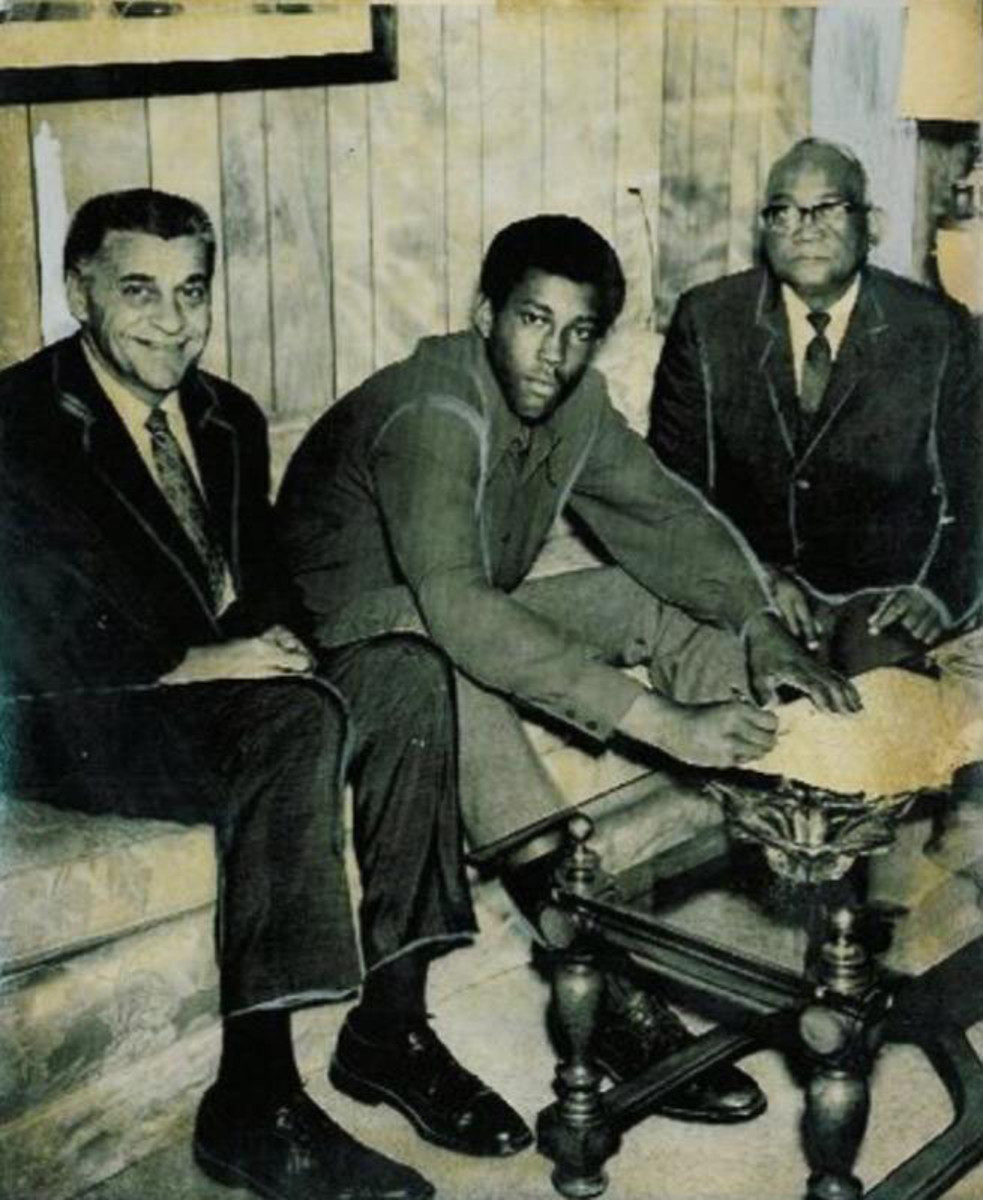

And 20 years after LSU wanted nothing to do with your father's father, the Governor of Louisiana walks into your grandparents' home and asks politely if your dad would consider becoming the first African-American player to integrate LSU's men's basketball team.

"Crazy, right?" you say when you find all this out.

No. It's almost surreal.

It's why you become a vice president with the players’ association, why you meet with cops and the community after a tragic shooting, trying to put yourself in both of their shoes. And you facilitate the reconciliation and healing—because your last name is Temple. And that's what you do. That’s what you learned growing up—from your father and from the elderly man in the wheelchair, who died when you were 10.

Collis, Sr. (C.B.) and Shirley settled in Kentwood, a town of less than 3,000 hard off Highway 55, in the nooks and crannies of the Mississippi-Louisiana border in 1960. They became full-time educators after they were married. She earned a degree in English from Southern and got her masters in humanities and guidance counseling from Atlanta University. She became an English teacher and guidance counselor. Collis became principal of Louisiana’s first all-black high school, Dillon Memorial.

Change comes embarrassingly slow in the South. Race-mixing wasn’t encouraged then. But by the time his son was a star athlete, schools in Louisiana began to integrate. “If you take that movie, Remember the Titans, it’s about 80 percent of what happened to me and him,” Collis Jr. says of his relationship with Spears.

He started getting serious looks from recruiters his senior year in both sports, including Nebraska, Kansas and Colorado. Collis visited USC and also thought about Houston, because Elvin Hayes was from Louisiana and he went there. LSU was the furthest place from his mind—until his father forgave the school that once wouldn’t admit C.B. but now suddenly wanted his son to be a racial pioneer.

His reasoning was simple: “Black people in Louisiana have paid to have LSU be the best school in the state by paying taxes,” his father told him. “We all participated in the educational process. So you need to go to LSU.”

His decision split the family for a time. Brenda, one of Collis’s five older sisters, didn’t want her brother to deal with the slurs and the ugliness she knew would come – even though she eventually would graduate with a degree in English from LSU in Collis’s freshman season.

She sat in on every LSU recruiting visit. If Press Maravich, LSU’s coach and father of the team’s star, Pete Maravich, regaled Collis with tales of how wonderful life on campus was going to be for her brother, Brenda would counter: “But what about the awful things happening to other black students on campus; you think he’s going to be immune to them

“I knew—because some of the other black kids I went to school with had mental breakdowns during their time at LSU, disappeared from campus forever,” said Brenda. Brenda Temple Tull now lives in the Hillcrest section of Washington, D.C., and runs an aerospace engineering firm with her husband and children. It doesn't take her long to go back to Louisiana, 50 years ago.

“I remember us pulling down the state flag because they refused to lower it at half-mast after Martin Luther King was assassinated. I was part of the Black Student Organization on campus. I remember the things that were said and done.”

Brenda also knew how Collis and her sisters were raised—by willful, convicted parents who imbued their children with strong constitutions. “Collis was not the type to just take something. I was truly worried the mental strain of being the first black player in school history would just overwhelm him."

Collis: “She cried when I signed with LSU. She told me she didn’t want me to deal with what was going on.”

By the time Garrett and his two older brothers came along, though, the scars and misgivings about attending LSU were gone. "He was strong enough mentally and emotionally to deal with it all, and surely it paved the way for others," Brenda said.

Collis Jr. still works at 66. He owns and caretakes about 25 group homes for the developmentally disabled, mentally ill, foster kids and other juveniles—housing nearly 300 people nightly. He says he still speaks to Jamie Spears, too, connecting with him last about eight months ago.

Collis Jr. used to take Spears’s oldest daughter fishing in a nearby Kentwood pond, where they’d reel up fat catfish and brim, and clean and fry them the same night. “Britney could fish,” he says now. “She loved it.”

Garrett would become an LSU man, too. By the time Garrett came along, the scars were gone. Part of his decision had to do with his childhood AAU teammate and friend Glen “Big Baby” Davis signing with the Tigers. They became extraordinarily close when, as a high school sophomore, Davis moved in with the Temples. His mother could no longer care for him. Davis and Garrett still catch up like brothers when they can, and it’s no wonder “Big Baby” started up his own foundation almost 10 years ago for orphaned children. Davis played in the NBA for eight years. After his career ended he, however, have his own brush with the law in 2018.

“Someone touches you, you touch another and they touch still yet another person, help them in life,” Collis says. “Garrett learned that from me and I learned that from my parents. I’m tremendously proud of him. He gets what life is about.”

The Temples left Kentwood a generation ago, moving closer to Baton Rouge. C.B. died in 1996. Shirley passed in 2005. But a piece of Kentwood remains with them, about several actual acres. Collis, Garrett and his brothers bought Dillon Memorial, built in 1911, and its surrounding property recently. Garrett held a basketball camp this summer in the same halls where C.B. educated young black men a half a century ago.

Months earlier he had been in the middle of Sacramento’s scalding racial cauldron after the death of Clark. Protesters blocked the entrances to two games, one of which was played before a smattering of fans. Garrett was instrumental in having the Kings partner with Black Lives Matter Sacramento. More than that, he facilitated formal town halls with law-enforcement officers and the black community.

“If people could only see the roots of where it all comes from—the history between African Americans and the police force and how it developed over time,” he said. “I don’t feel every police officer that’s killed an unarmed black man was personally racist and don’t like black people, for whatever reason. I think most of it comes from fear, from an ingrained bias put upon them through society. That fear comes from the way blacks have been displayed through media, movies, news.

“I actually talked to some police officers about this situation and how they would go into it, because they have the most difficult job in America, putting their lives on the line every day. I actually asked, ‘If I don’t see a gun, how can I shoot?’ And their response is, ‘Seeing the gun is too late. Maybe your life is taken.’ That was hard to get my head around because, you know, you’re there to protect and serve—not to kill first and answer questions later. I still believe it boils down to fear, a fear that comes from an implicit bias that’s brainwashed all of society to view blacks—especially black men—in terms of being fearful of them.”

He pauses, thinks hard about what he will say next.

“My background made me get involved,” Temple says, sitting in the lobby of Firestone Tire last month in Memphis, waiting for a nail to be removed from his driver's side front wheel. “I’m an athlete and I have this platform. When you have a voice where you can reach multiple people, maybe even millions, you should use that platform. If you feel there are voices that need to be heard that can’t be heard—and you feel what they feel—you speak for them.”

He says he was meant to be traded to Memphis, even for half a season.

“The first thing I did when I got traded was visit the site of where Martin Luther King was shot,” Temple says. “I can't tell you the feelings I felt, but I knew I was supposed to feel things and that they would make me do more for others. And that's why we're really here, right? I mean, I want to play four more years. But I also want to change how the world is today in any way I can.”

The next question was going to be about basketball, how he got into a fight with his teammate Omri Casspi in Memphis in a closed-door meeting when things went sour for the Grizzlies. But it just seemed trite, given he had to go to a Black History Month panel that night and tell the story of C.B., Shirley, Collis Jr., and how a Louisiana family made a difference beyond giving an NBA starting guard rest.