Owning the Paint: Willie Cauley-Stein Can Be the NBA's Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol

NEW YORK — It’s rare that Willie Cauley-Stein finds himself looking up in awe. But this is one of those moments. It’s Friday night and the 7'0" Sacramento Kings center is standing inside The Brant Foundation Center, which is hosting a private, inaugural exhibition at its 16,000-sq. ft. New York location tucked away on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Cauley-Stein is here ahead of his club’s matchup against the New York Knicks on Saturday afternoon, getting focused by immersing himself with his off-court passion: art. Right now, he’s staring in wonder—before him are 16 pieces by the iconic American street artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat, lining a wall reaching over a story high.

The depictions speak volumes to Cauley-Stein, who’s an artist away from the hardwood. He’s long-held an affinity for street art, but seeing the work of one of the most influential American street artists, in-person, is astounding. Seventy of Basquiat’s scribbled, primitive, graffiti-style paintings are being housed here, spread throughout the wide, quiet rooms of the building, which, in its closing hour, is nearly empty.

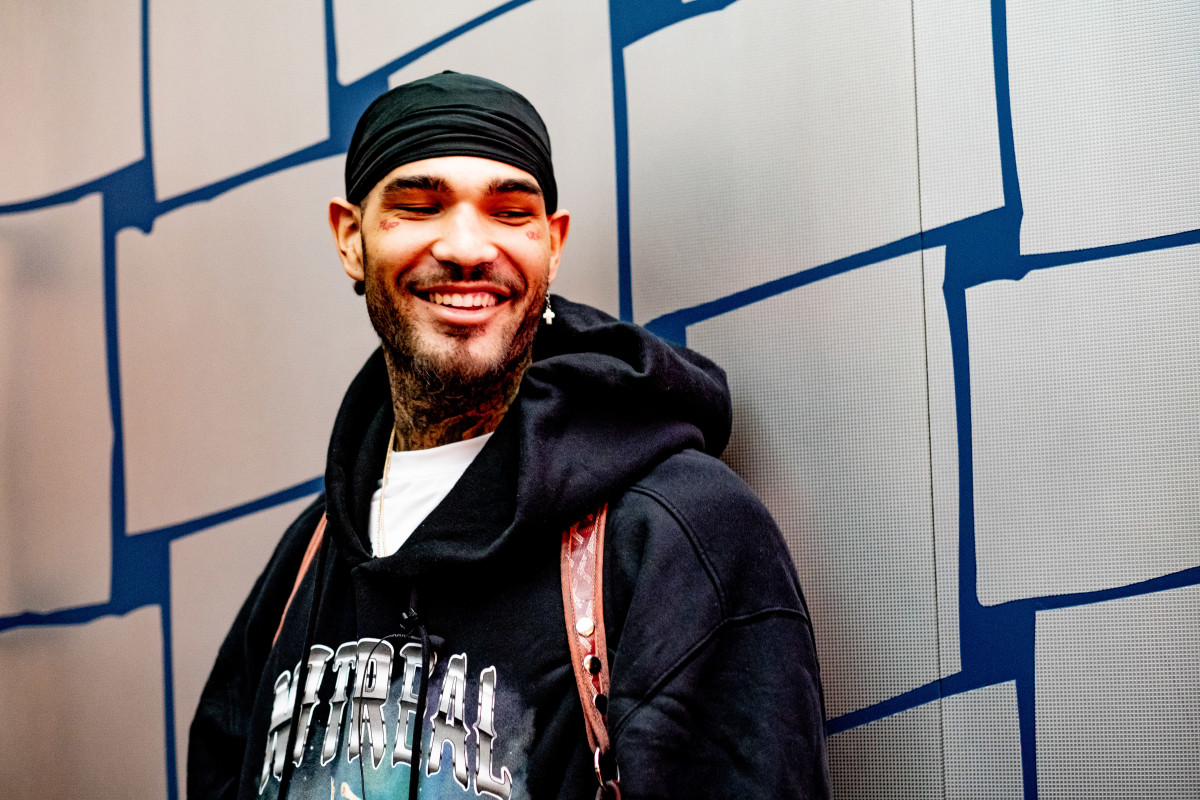

Cauley-Stein is eyeing the works along the wall, questioning how the canvases are stretched and how the placement for different designs was determined. Like Basquiat’s work, the man observing it is distinguishable, even if his unassuming demeanor would suggest otherwise; if Cauley-Stein’s height doesn’t make him stand out, the tattoos on his face, arms, hands, legs and body do. However, they are not the mark of Cauley-Stein’s art-obsession. On Instagram (@pr00fessortrill), he’s posted personal iterations of The Joker, Jimi Hendrix, a few landscapes, and other works, sharing a glimpse into his artistic talents.

Similar to the way artists manifest their own styles through their work, basketball players offer a varied assortment of character on the court, touting individualized skill sets, shooting forms, wardrobes and personalities. It’s within these elements of originality that Cauley-Stein finds both art and basketball to be most alike.

“You hoop with a certain expression,” he says. “That’s your art. You’ve crafted it, so it is your art.”

But it’s when Cauley-Stein is crafting his artwork, untethered from the bounds of an NBA court and the general pressures of life, that he experiences the most freedom. Something about taking in another artist’s work engenders a similar feeling.

“When you’re painting,” Cauley-Stein says, “you don’t really need to—you’re just gone. You’re just in it.”

When Cauley-Stein first started creating art, it was only drawings. But about two years ago, he estimates, his mental coach once correlated his on-court performance to a painting he had made. Ever since then, he’s grown enamored with painting, which he says provides a space to evade stress.

Now a fourth-year NBA pro, Cauley-Stein let’s inspiration dictate when he paints within the structure of an 82-game schedule. “We’re busy,” he says of NBA players, “but not as busy as y’all like to think.” The Kings hold set practices between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. After that, players are essentially free from obligation, presenting Cauley-Stein a 20-hour window. Sometimes, he’ll devoutly paint throughout an entire week, but there’s periods where he won’t paint for a week or even months. Following some games, he goes home and paints well into the night. Nevertheless, whenever he picks up a brush, there’s a sense of purpose.

At 25 years old, Cauley-Stein’s passion for art is now a vibrant flame. But as a child, it admittedly took some time to stoke. He finds it interesting whenever he’s asked if he took art classes when he was younger, admitting that he usually reverts to the same answer: His grandmother placed him in an art class when he was in third grade.

“I didn’t want to,” Cauley-Stein says. “She just kind of put me in there.”

He remembers the teacher—a woman whom his grandmother had befriended at a waterobics class—painted oils and taught him how to create landscape art. He didn’t like it until a friend joined him. Then he found it cool.

Nobody else in Cauley-Stein’s family paints or draws. He says his mom did crafts, but as far as illustrations, he’s the first to pick up the mantle.

“I wish I still had all of my old schoolwork,” he says, laughing. “I’d just have all the sketches around the schoolwork, and none of the schoolwork done. Just sketches all around. I was always doodling something.”

The first artist Cauley-Stein became familiar with was American street artist Keith Haring, who he researched for a class project. In junior high school, he took his first "real" art class. He went on to do so every year from sixth grade through college. When he picked up painting, his first instructor was the renowned Bob Ross, whose art shows that aired on Netflix introduced Cauley-Stein to basic fundamentals.

At first, Cauley-Stein was skeptical, specifically questioning the amount of scenery depictions. But then he began to pick up the nuances of Ross’s instructions, noticing intricacies such as how a particular paintbrush tip helps create a tree.

“And it’s like, ‘Oh, it’s the freaking techniques that he’s teaching us!’” Cauley-Stein realized. “So I’m like, I’m gonna start watching more. I need to learn all these techniques because I want to start making my own concepts and things like that instead of just picking a superhero to paint.”

Though conjured out of unplanned ingenuity, Cauley-Stein’s superhero illustrations, and his other early works, are significant. They would help garner the attention of the man looking to help him take the next step in his art career.

Despite his passion for art, Cauley-Stein doesn’t boast a massive collection at home. “I have a lot of art in the house,” he says, “but it’s mine, friends’. Not necessarily—like, I didn’t spend thousands of dollars to attain it. It’s authentic, at least.”

By his own admission, Cauley-Stein hasn’t yet put himself in position to purchase art. Enter Gardy St. Fleur.

St. Fleur is a New York-based personal art adviser, private dealer and collector. The New York Times once described him as “a liaison to the art world” for the NBA’s aspiring collectors. He works with several different NBA players, teaching them not only about art, but also how to distinguish fine art from regular, understand its value, and how collecting can become a worthwhile investment.

Most of the players he’s assisted are older. His past associates include former NBA All-Stars Deron Williams and Alonzo Mourning. He’s helped current NBA veterans such as Dallas’ Courtney Lee, Houston’s PJ Tucker and Minnesota’s Jerryd Bayless. But he’s also aided younger NBA players, including Miami’s Justise Winslow and Brooklyn’s D’Angelo Russell and Caris LeVert.

“I don’t work with everybody,” St. Fleur says. “It’s some players worth working with because they’re so into it. But you want someone that really has an interest.”

St. Fleur, the son of a Haitian art collector and commissioner, aims to enlighten those he works with. In addition to meeting players, showing them about art galleries and connecting them with artists, he sends them books, and shares links and videos to historic illustrations, pieces and time periods. He even exchanges texts with players explaining how they can further their comprehension of art.

Players do the legwork of St. Fleur’s promotion. A player who collects art could mention how they’re involved in art collecting within the locker room, piquing the interest of a teammate. Curious to know more, they’ll inquire. It’s a word-of-mouth net that, when cast, typically reels in those with a legitimate desire to dip their toe in the currents of the art world.

Cauley-Stein’s enthusiasm for creating art was enough to suggest that a meeting with St. Fleur could prove fruitful. The two were connected through Cauley-Stein’s agency, Roc Nation Sports. Upon learning of Cauley-Stein's prior interest in art, St. Fleur saw that it would be worth a meeting.

Standing inside the hallway of the staff entrance along the side of The Whitney Museum of American Art, St. Fleur and two of his associates are awaiting the arrival of Cauley-Stein.

Around 5:15 p.m., Cauley-Stein arrives, wearing a black hoodie that reads “Seeing Things” in blue script above its hem. Four others are with him: His three friends—Rexx, who grew up with Cauley-Stein in Kansas, along with college friends Yoku and Burks, who’s filming the visit—and his manager, Caitlyn. The group converges and begins its trek through The Whitney’s Andy Warhol exhibits. A collection of works done by the American recognized for leading the pop art movement are on display here through the end of the month.

Almost immediately, St. Fleur is educating Cauley-Stein about the depictions they observe, raising his hands and mimicking the movement of brush strokes with his arms. Cauley-Stein is intently looking on, nodding his head in agreement. As he listens to St. Fleur’s lectures, he runs his thumb over a shiny ring on his left index finger; his right elbow rests bent to form a thinking posture, his right hand clutching his chin.

The interaction between student and teacher is engrossing. Cauley-Stein heeds the words of St. Fleur, reflects, then poses questions of his own. Just moments into the meeting, he asks about Warhol’s silk-screening process while observing his Flowers. At no point does Cauley-Stein appear shy. He’s in his element. If not for the large group and cameras feet behind him, he would blend in with any other visitor. His lanky frame bends forward to interestedly read artworks’ descriptions, and when he sees a piece he likes, his eyes widen and his mouth opens in exacerbation. He’ll enter thought, then moments later, break his silence to crack a joke. He turns to everyone to see if they’re as amazed as him when he notices the blurry mixtures of Warhol’s Abstraction.

“To see someone that was really interested in that,” St. Fleur later says, “I was really impressed.”

About 40 minutes later, Cauley-Stein and St. Fleur have finished weaving through the Warhol exhibit. Cauley-Stein is noticeably impressed.

“I feel like you’ve gotta see this if you’re an artist,” he says.

St. Fleur has another stop for his pupil to see. While the group awaits transportation to the next venue, a teenage worker at The Whitney, approaches Cauley-Stein asking for an autograph. It’s the first and only instance of the night, which isn’t surprising to St. Fleur. He’s taken the subway with NBA players who have similarly gone unbothered while visiting art studios in Brooklyn’s Bushwick borough.

The worker’s query doesn’t annoy Cauley-Stein. In fact, he appears delighted to chat with someone about art.

“You like Warhol?” the worker asks.

Cauley-Stein grins. “I like everything,” he responds as he signs a piece of paper.

The teen gives Cauley-Stein a recommendation, pulling out his phone to show the Brooklyn Museum’s recent “Soul of a Nation” exhibit. The interaction lasts for about a minute before Cauley-Stein must depart.

“You made his day,” Cauley-Stein is later told.

“S---," he replies, “he made mine.”

“I really want you to see Basquiat,” St. Fleur tells Cauley-Stein as they leave The Whitney.

The sun is setting over the Hudson River when the group arrives at the second venue. As everyone exits their rides, a man on the steps of the building quickly ushers them through a pair of black doors. Inside, the Brant Foundation Center, a by-appointment-only locale, is hosting its private Basquiat exhibition scheduled between March 6 and May 15.

All 50,000 tickets have been sold. But St. Fleur has brought Cauley-Stein and the others, much to the bewilderment of the gatekeeper, who later says he was only expecting two guests. Everyone files into a dark front lobby that is smaller and more intimate than The Whitney’s.

“I like this a lot more,” Cauley-Stein says.

Moments later, he is standing in a spacious room full of Basquiat pieces. He’s compelled approaching Warrior, a sword-wielding figure depicted in front of a blue and yellow background. Later, he walks up to Anthony Clarke, a portrayal of a man wearing a grey long coat and matching hat. One of his friends jokes that the illustration could be to scale, rivaling Cauley-Stein’s height.

Initially, the look in his eyes says everything he doesn’t. But sporadically, his admiration, as well as his friends’, becomes tangible excitement in the form of delighted murmurs, chuckles, oohs and ahhs.

Cauley-Stein, St. Fleur and the trailing entourage head down a winding black staircase leading to another room. There are no signs of fatigue. Cauley-Stein is as engaged as he’s been all night. He turns a corner behind a wall, finding Basquiat’s collection of minimized works portraying famous boxers such as Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson and Muhammad Ali. He wanders to Basquiat’s Cassius Clay, a white drawing on a red background.

It’s a simple-looking work depicting a powerful subject. Cauley-Stein is fixated on the piece, as if channeling some sort of deeper connection. Then peacefully steps away.

“It’s cool learning it now,” he later says, “because I understand it. Whether I had learned this or not as a kid, I wouldn’t have understood it. Now, it’s like, OK, I can take what I just learned by walking around here and putting in my own type of feel and my own inspiration to further my artist-self. It’s crazy.”

Cauley-Stein’s trip was meant to serve as both a lesson on art as well as an introduction into art collecting and dealing, but it hasn’t convinced him to step into the game just yet.

“This is like the first time that I’ve actually even thought about art dealing or buying and trading art,” he says. “That’s something that I would obviously have to learn because there’s a lot I don’t know.”

In the meantime, he knows that he wants to focus on developing his own artwork.

The earliest piece Cauley-Stein can recall having put on the refrigerator is a drawing of a horse. He thinks his grandmother still has it, his first “big boy” drawing. Now, he aspires to one day have his work displayed in a museum. Especially after seeing the Warhol and Basquiat exhibitions; before then, he was unsure of how to create a gallery and rearrange sizes.

“Now,” he says, “it’s kind of like, knowing what I’ve learned after this experience today, now I know how to make a gallery or set up a gallery. Or what’s the meaning behind it all, which is obviously everything.”

St. Fleur wants to give him the chance. He says Cauley-Stein has an artistry in him, and desires to do a two-piece show with him in either Los Angeles, New York, or both. He’s not sure how many illustrations they would feature yet though. They’re still in the “research phase” of the idea. In the meantime, St. Fleur is encouraging Cauley-Stein to experiment off the canvas and dabble with other mediums and methods. St. Fleur even mentioned Gutai pieces from the 1950s, hoping Cauley-Stein draws inspiration from hearing about the Japanese artists who painted with their feet.

Before the meeting, Cauley-Stein had been entertaining ambitious ideas on his own. He once created a painting of Bob Marley and a lion, and added his face tattoos to Marley’s. Since then, he’s tinkered with integrating ideas on designer clothing, one day deciding he would draw on Louis Vuitton.

“It’s like using designers as canvases,” he says.

Cauley-Stein is currently in the midst of kickstarting his collection of authentic paintings, “Addicted to Sauce.” One piece depicts a syringe being dipped into a Louis Vuitton bottle, pulling out “the sauce,” as he puts it. Another features Chanel Cs being melted down on a spoon. The symbolism of the collection serves to highlight the addictive nature of hypebeast fashion culture.

Cauley-Stein’s journey has only further inspired him to invest in his own work. The first step is to develop a catalog of his original pieces. The next is to put it on display for people to see.

Eventually, with his work, Cauley-Stein wants to incite the same fascination that he felt staring at the wall of Basquiat works just moments ago. As his tour of the Basquiat exhibit comes to a close, he stands next to one work, Untitled (Savoy, 1986), listed 94-by-136 ½ inches—or 7’10”-by-11’4 ½—as he explains his vision.

“I want to have sizes like these,” he says, pointing. “Before, I was working on these little [pieces]. But now, after seeing this type of stuff, it’s gotta be bigger. The bigger it is, the better it’s going to look.”