Metta World Peace Is From the Future

Metta World Peace was 32 years old when he found out what the word “arsonist” meant.

The then-Laker was walking in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles—near the corner of Veteran Ave and Ohio Ave—when he was approached by a stranger and his girlfriend.

“I was walking on the street, and the guy said, ‘You really inspired me to change my ways, I used to be an arsonist,’” World Peace remembers of the day he first heard the word. “I didn’t even know what an arsonist was. In my mind, I was like, was he spray painting buildings? I was like, okay, he’s a graffiti artist. I called my partner, and I told her 'This guy said I stopped him from being an arsonist.'

“She was like, ‘What?!’” I said ‘What the hell is an arsonist?’ They said somebody who likes fires.”

So what would inspire a complete stranger to approach Metta World Peace only to let him know he was the reason he stopped setting things ablaze?

“I think it was because I went on TV and thanked my psychiatrist.”

In more ways than one, World Peace—who entered the NBA as Ron Artest in 1999 before changing his name in 2011—is ahead of his time. Though he’s largely remembered as a bruiser, the 39-year-old would have been a perfect fit for modern basketball. His rugged defense, underrated scoring ability, and solid jumper would have made him a 3-and-D monster in today’s game. Imagine World Peace playing the P.J. Tucker-role for the Rockets, or the Draymond Green-role for a Warriors competitor. In a smaller league that values dependable offensive players who can guard multiple positions, World Peace would have been of great value to any contender.

It’s World Peace’s off-court revelations that make him an even more compelling figure. He was outspoken about his mental health struggles in a time long before the NBA was running PSAs during playoff games. In 2019, Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan are applauded for their willingness to speak out. When World Peace thanked his psychiatrist after helping the Lakers championship in 2010, he was mostly laughed at.

“Some people said it’s crazy,” World Peace says when he thinks of the reaction now. “Whatever. It’s a psychiatrist, it’s a service man. Everybody has a psychiatrist.”

World Peace has long sought the help of counseling to help with his mental health issues. He was 13 years old when his mother made him see a social worker for the first time to help with his anger outbursts. World Peace was frequently getting into fights in his home neighborhood of Queensbridge, a public housing development in Queens. (World Peace claims he was first suspended from school when he was five years old—for fighting a girl.) Though he was shy about being sent to what fellow residents called “the Crazy House,” World Peace appreciated having someone he could talk to. He attended counseling throughout his NBA career, and while he wasn’t always receptive to the help being offered, World Peace speaks highly of seeking help.

“Therapy is very important. If you can’t talk to your family about issues, who the hell are you going to talk to? You got to talk to somebody. That’s why you can’t judge people. People are constantly making mistakes, constantly.”

“The brawl hurt my pockets, man,” World Peace says with a hint of a smile.

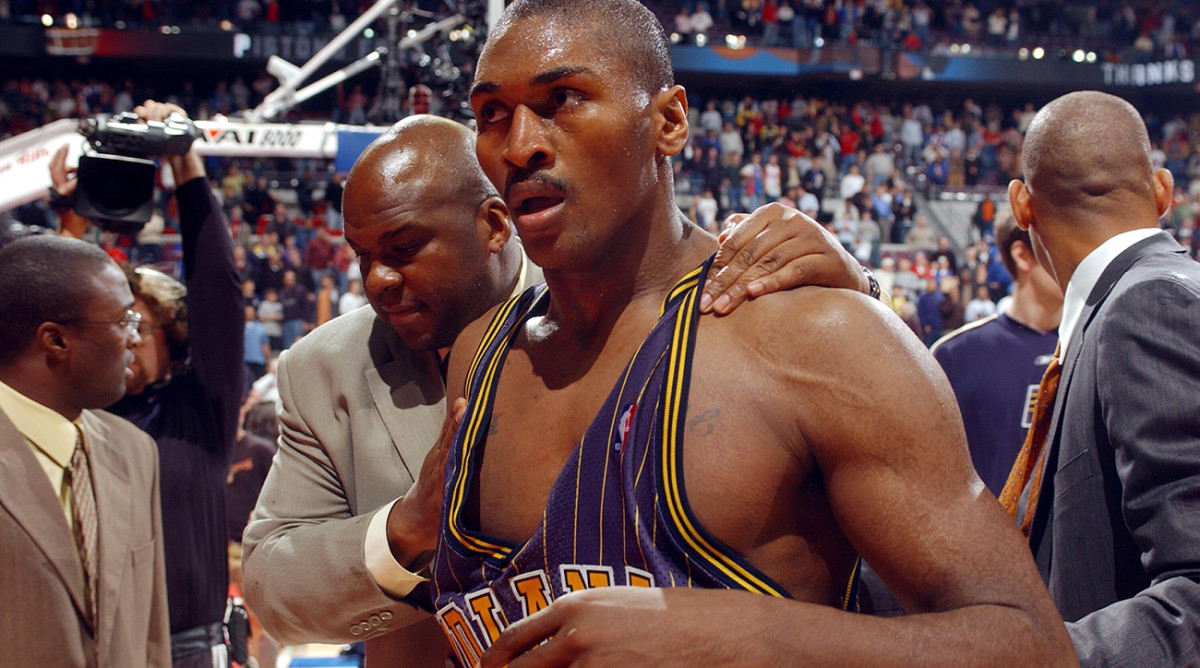

The first thing everyone thinks about when they think of World Peace (uh, the person) is November 19, 2004’s Malice at the Palace, an infamous night in NBA history that is the top line of nearly every story about him. It’s a big part of the documentary, Quiet Storm, that aims to tell World Peace’s story (premieres May 31 on Showtime). What could drive someone to confront—and physically engage with—a fan in the stands?

It’s worth noting World Peace’s upbringing in Queensbridge, a a six-block, 96-building community that was supportive of its own but filled with dark paths. The documentary dives into the fuller picture of World Peace’s life. The 2004 Defensive Player of the Year learned to cook crack at the age of 13, and was even younger when he was a witness to the police brutality of Richie Luke. Problems in Queensbridge were often solved with violence, authority was mistrusted, and World Peace was without a doubt far from the only child—in Queensbridge, or in other similar communities—dealing with the mental fallout of growing up in such an environment.

“If I’m at the bottom, you can’t expect me to have a silver-spoon etiquette,” World Peace says. “In Queensbridge, there are no resources. There was no therapist.”

How would World Peace be judged if the brawl—as he calls it—happened today? There would still be a fair share of carnival barkers, or people using a coded word like “thug” to describe World Peace. It’s also possible there would be somewhat more understanding, a desire to to recognize why World Peace—at the time a star forward for the Pacers—felt the need to act the way he did. How would people react now if an athlete openly struggling with his mental state were accosted by a fan? Would the NBA—the same league that this year saw a team ban a fan for life for starting a verbal altercation with Russell Westbrook—still suspend World Peace for a full season? Society is far from fully empathizing with athletes—or having enough people in media who relate to their stories—but the Malice was a particularly perfect storm for people who didn’t like players who looked or acted like World Peace, and he paid the price in the resulting discourse.

“I didn’t attack myself, it was live on television,” World Peace says. “People skip—what the media did—they somehow got people to skip the first part. It’s clear as day what happened. Whether or not I was wrong, I get that. But don’t skip stuff, man. Tell the whole story. I was hit. I was attacked.

“You can’t do that man. You should not allow people to hit people, because now you set a precedent where it’s okay to hit players. That’s okay? It’s never okay.”

World Peace has some right to be angry for the way he was classified after the brawl. He was called crazy at a time when good-faith conversations about mental health were a rare occurrence in public. He was the target of racially-charged language at a time well before anyone cared to consider the experience of a black man growing up in the projects. But World Peace is not bitter. He’s not angry. He doesn’t seek revenge. Instead, he preaches what most people failed to practice when judging him—understanding and acceptance.

“I don’t know those people. It’s not like they check up on me,” World Peace says. “I don’t judge what people do. Whether it’s somebody at a coffee shop tweeting or a media person, you don’t know how smart or ignorant that person is. Nobody knows how smart or ignorant I am. I can’t judge people anymore.”

World Peace genuinely strives to understand. He repeatedly mentions how, despite his own plight, others have suffered as well, naming the LGBTQ and Native American communities as examples. He recognizes he was lucky to make it out of Queensbridge in the first place, saying the difference between him ending up in the NBA or jail might have simply hinged on the police walking away instead of knocking down the door the day he was in an apartment filled with crack. He wishes more people could be exposed to the experiences he’s had in life, from his traumatic childhood to studying math at St. John’s, to traveling the world and being introduced to new ideas and people. He also doesn’t believe people should be held to the standards a certain part of society has created.

“If I walk into someone's house for dinner, I don’t want to be looked at as different. Like, ‘Oh, it’s a black guy in my house,’” World Peace explains. “That should not be a f---ing highlight in your f---ing life. We’re all different. We all talk different. It doesn’t make one person smarter than the other. The words that you know, how you grew up, they way you present yourself, a good posture, that doesn’t make you any smarter than Jay-Z. The one thing that is constant is the soul, the purity of the heart. When I meet people, I don’t give a f--- how you look, or speak. It’s really about the soul.”

While World Peace seems to be genuine about acceptance—he mentions a couple times going on vacations in Vegas with “20 gay dudes,” a group of people he was ignorant about when growing up—he does yearn for accountability. World Peace would like all those who criticized him without knowing the full story—or without fully understanding the challenges someone like him faced—to accept some responsibility.

“I wish what the media would do is get the name of every person who called someone a thug, crazy, or hoodlum. Everybody should be held more accountable.”

One of the people World Peace would have especially liked to see held more accountable was Matt Lauer, the now-disgraced former Today Show host who interviewed World Peace not long after the brawl in 2004. According to World Peace, Lauer—who lost his job last year after a sexual misconduct scandal—told him he could go on the Today Show to promote the album he had spent all summer producing. World Peace, who would be missing a near-season’s worth of paychecks, perhaps naively agreed to appear on the show to talk about the album, but he was instead peppered with questions about the fight and his suspension. To many, World Peace looked foolish holding up a CD in the middle of a serious interview.

“I want to tell Matt Lauer he’s an a--hole,” says World Peace. “Meet him for lunch, he can order his burger. And I’ll be like, ‘You need to know you’re an a--hole.’ That’s it. I tell my daughter the same thing when she’s like acting like one.”

World Peace says he doesn’t really care about how he is viewed, even as he conducts a press tour for his documentary. Some people may try to paint his current persona, which, thanks to stories like this one, has been “redeemed” from its nadir in 2004. The media still tries to fit World Peace into a box at times. During a sitdown for one TV interview, World Peace was asked if he thought the brawl was the worst night in NBA history. He responded with his own question, “What about all the nights black players weren’t allowed in the NBA?” The exchange was cut from the final piece.

World Peace’s story is less about a comeback, and more about perceptions, and the way perceptions are made, ever-so-slowly changing from the flashpoint moment of his career. World Peace himself rejects the comeback narrative.

“If you think I’m a good guy now because I’m doing the things you want, I don’t give a f---.”

World Peace is doing the things he wants, like starting his own businesses, investing in others, and trying to give back to kids who are in a similar position to the one he was in. According to his friend and business partner Naquan White, World Peace is a “humble giant” who strives to help others, and extends himself to teach kids trying to make a better life. In Queensbridge, it’s like World Peace never left. When he walks through the neighborhood, people of all ages approach him to say hello. (One elderly woman, who knows World Peace as “Ron Ron,” asked him if he was “still playing his basketball.”)

The attention on World Peace now doesn’t necessarily make him comfortable. While he seemingly enjoys the spectacle of social media—like asking White to film him while he answers a question about why he wants to coach the Lakers—he’s also wary of the limelight. He will often block people from following him, and on multiple occasions he’s deleted his Instagram so he can start over with zero followers. World Peace admits the attention he received in the NBA sometimes made him think he was better than people, and now he tries to remind himself of the downsides of fame so he doesn’t grow overconfident.

Though he aims for understanding, World Peace is not fully satisfied. He feels his career should have turned out better, and he thinks the brawl derailed would could have been an MVP season for him. (His basketball legacy will likely be defined by the fight and his championship run, which largely ignores how skilled he was in his prime.) World Peace is also not perfect. While he’s come to understand what led him into the stands in Detroit, in would be unfair not to mention his domestic violence arrest from 2007, and World Peace must ensure that type of behavior is learned from—and remains in the past.

For now, World Peace mostly seems to appreciate what all the experiences of his life—which exist on a wide spectrum—have taught him. He grew up in Queensbridge, at one point living with 15 people in a one-bedroom apartment, and eventually found himself making millions of dollars in the NBA.

“Nobody knew i was going to make it,” he says. Then he did make it, and the money allowed him to chase whatever he wanted. “Now I can travel anywhere I want to go. Growing up, you see Disneyland, you see rap videos, you see jewelry, you see amazing asses on BET. Now you can do all of it.”

World Peace has done all of it, and more, from being a national pariah after the brawl, to winning a championship with the Lakers, to learning about Buddhism, to serving as a coach for the Lakers’ G-League team, to having a documentary made about his life journey. At 39 years old, World Peace has already lived multiple lifetimes worth of experiences. For the people who still don’t understand him, it would seem they need to catch up.