Western Union: A Blue Chips Oral History

Sports Illustrated’s annual “Where Are They Now?” issue catches up with the stars and prominent figures from yesteryear—past features have included Sammy Sosa, Brett Favre, Dennis Rodman, Tony Hawk and Don King. The 2019 issue features an inside look into the new life of Alex Rodriguez, Yao Ming’s mission for Chinese basketball and more.

For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Title card: Early 1980s. Fade from black. A hopeful Hollywood screenwriter is reading the newspaper and finds himself enthralled by the recruiting scandals sweeping college athletics, so he does what aspiring scribes do in inspiring moments like these: He writes a screenplay about it. In his story, a college basketball coach—Pete Bell, at the fictional Western University—is trying to reconcile his desire to run a clean program with his hunger to win. Bell ultimately betrays his morals, bribes players to come to his school and then does battle with his demons.

In real life Ron Shelton, a former college player himself, polished off that script and then . . . waited. And waited. Shelton, not one to sit still, would write some of the greatest sports movies ever—notably Bull Durham, which came out in 1988, and White Men Can’t Jump, in '92—before a studio finally scooped up his hoops-scandal script. That film finally landed in theaters 25 years ago. And, acting bona fides aside, the payout was something else. For better (Shaq and Penny) and for worse (Bobby Knight and Dick Vitale), Blue Chips will be remembered for bringing together some of the biggest basketball guns of its time.

I. “I DO SAY ‘BITCH,’ AND I DID TAKE MONEY!”

RON SHELTON (writer and producer) It seemed like these problems in college sports hadn’t been addressed in popular media very much—the pressure to win, exploitation of high school kids . . . . It’s old news now, but back then I thought it’d be a good subject for a movie.

MICHELE RAPPAPORT (producer) That script was in development for 12, 13 years. People were afraid it wasn’t commercial.

SHELTON Nobody was interested in anything except heroic sports movies.

RAPPAPORT We had lots of meetings with actors interested [in playing Bell]. Al Pacino. Andy Garcia. Kurt Russell . . .

While Shelton waited for Blue Chips to come together, he decided to take one scene from his script and turn that into its own movie.

SHELTON The first scene with the character that Shaquille [O’Neal] plays in Blue Chips, in the movie it takes place in the Bayou. Originally, though, it was written for the street courts of Compton. I took that and said, “I want to make a whole movie about that world.”

RAPPAPORT White Men Can’t Jump.

SHELTON I wrote that in ’91—one draft and it went right into production. Very different models. One was a sprint; the other was a triathlon.

RAPPAPORT I remember asking an executive at Fox [which ultimately produced WMCJ]: “We have two basketball movies, and you’re going to make White Men first?” They said, “No, we’re going to make that one only.”

SHELTON So I wrote and directed White Men Can’t Jump—and then suddenly everybody wanted to make Blue Chips.

That script eventually landed at Paramount, in the hands of The French Connection director William Friedkin, himself a huge basketball fan. Casting started with Coach Bell.

NICK NOLTE (actor, Coach Bell) Billy Friedkin and Ron Shelton came out to my house with a script. They said, “Go upstairs and read it right now.”

SHELTON We brought pillows under our arms. “We’re going to sleep here. We’re not leaving until you commit.”

FRIEDKIN We told him we would camp out on his lawn.

NOLTE I said, “No, no, no, no, no—you guys have to leave.” They came back a couple of days later.

FRIEDKIN Nick had recently been named PEOPLE’s “Sexiest Man Alive” and he was embarrassed about it. He did not want to be considered a pretty boy. He was looking for more complex roles.

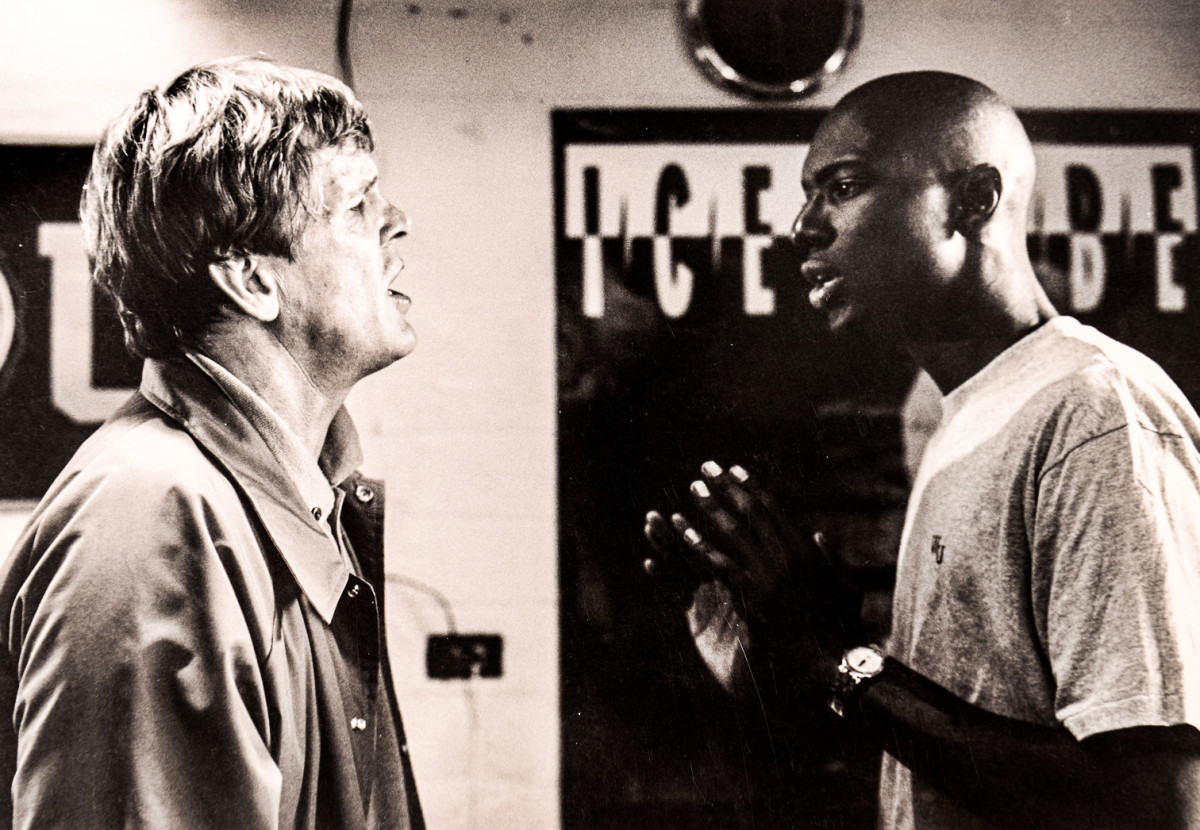

NOLTE Billy took me aside and discussed how we would approach it.

FRIEDKIN I told him I’d take him to Bloomington and have him sit with [Indiana coach] Bobby Knight. I think that’s what convinced him. Nick loved to research a role.

Friedkin connected with Knight through their mutual friend Red Auerbach and persuaded him to be in the movie. Knight, it turned out, was a fan of The French Connection, and he found Shelton’s scriptto be an accurate depiction of college basketball. (Friedkin says Knight “confirmed everything in that script.” Knight, in declining health, couldn’t be reached for comment.) Nolte shadowed the coach for about two weeks during the 1992–93 season.

FRIEDKIN I wanted Nick to absorb everything Bobby did, on the floor and off. His character is based on Bobby.

SHELTON Like any character, he’s a composite.

NOLTE I had my assistant shoot a video, and he edited it down to 30 minutes of Bob Knight, all his gestures, frustrations, emotions.

MARQUES JOHNSON (actor, assistant coach Mel) Nick’s trailer was wallpapered with notes and plays from his research.

FRIEDKIN That first scene in the movie, in the locker room, where coach Bell keeps storming out and then back in—that was pure Bobby Knight. He would do that!

After Nolte, producers had three major roles to fill: a trio of high school recruits who accept bribes to attend Western. The first part filled was that of Neon Boudeaux, a big man from the Bayou.

SHELTON I said, “The trick here, Billy, is you’ve got to cast a guy who can play.” Friedkin said, “Why don’t we get Shaquille O’Neal?” He’d just been drafted [by the Magic]. I said, “You’ll never get Shaquille!”

O’NEAL I was at the Four Seasons in Los Angeles; Billy Friedkin was there. I walked in and everybody started going crazy. Billy was like, “I’ve been looking for you.” You’ve been looking for me? He said, “I’m Billy Friedkin.” And I was like, “Oh, s---, you directed The Exorcist? That’s me and my mom’s favorite movie!” He said, “I’m shooting a movie about basketball players, and I want you to be in it.”

NOLTE Billy and I had to go down to Orlando. We were in a hotel. Shaq and his agent came in. Shaq had read the script. He said, “I want to do this film.” Then his agent stepped in and said, “But, we’ve got some problems. He can’t say ‘bitch,’ and his character cannot have taken money.” And Shaq interrupted: “No, that’s why I want to do the movie! I do say ‘bitch’ and I did take money!”

In the movie Neon does drop the B-bomb, and he does accept a Lexus, though he says he never asked for it. As for O’Neal’s own past with college payoffs, he tells it a little differently.

O’NEAL Ah, hell no, never. I had a lot of stuff coming my way, and I was like, Nope. In college my father told me, “You’ve been broke for 17 years; you can be broke for two more. Don’t sell your soul.”

FRIEDKIN Shaq confirmed everything in that film. So I knew we were on the right track. This wasn’t just a fantasy basketball movie.

Next up: Butch McRae, a guard from Chicago whose mother asks coach Bell for a new house and job.

DAN PARADA (extras casting) We were looking for the best basketball player, who looked the youngest—someone who was going to go in the [1993 NBA] draft.

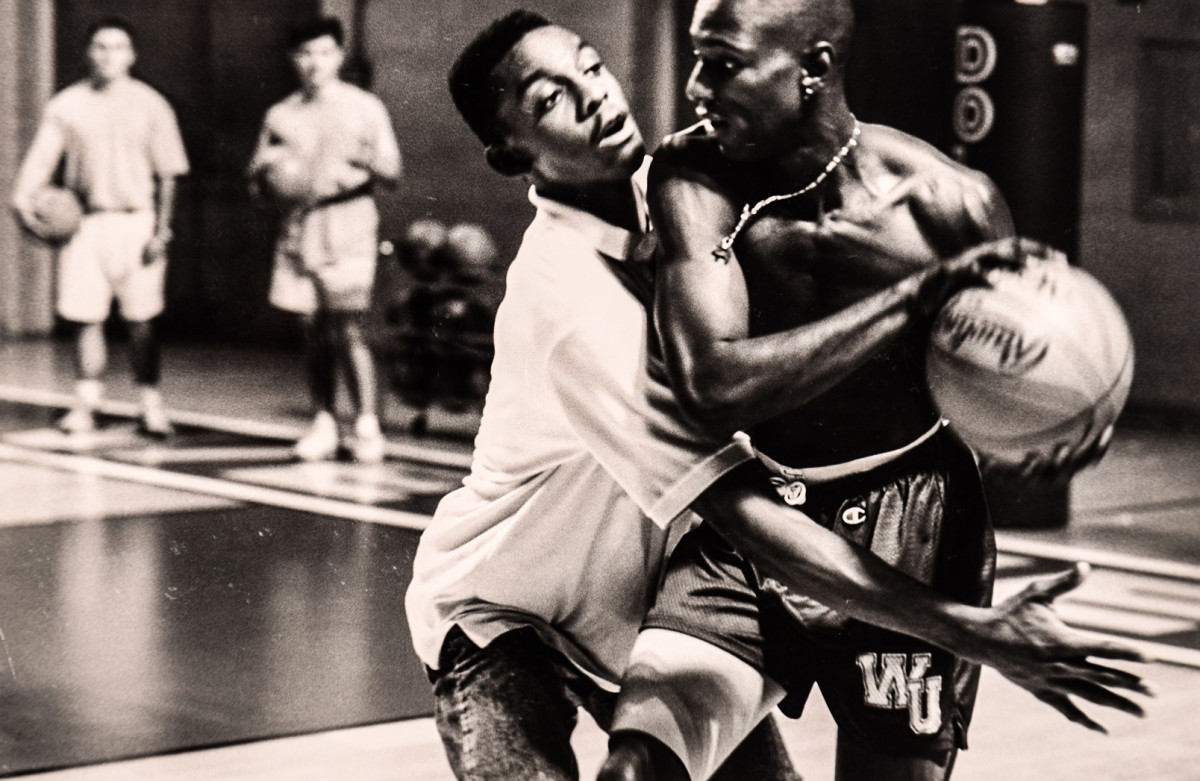

KEVIN BENTON (assistant basketball coordinator) I ended up at my desk and I picked up a magazine with an article about [Memphis point guard] Penny Hardaway. I didn’t even really know who he was; most people didn’t know all the small-school guys back then. And I thought: I’m going to get in touch with this guy.

HARDAWAY My agent said they were looking for real basketball players. They didn’t want actors.

BENTON So Penny came out [to Los Angeles], and for a whole day I worked with him on this role.

HARDAWAY I had to do a reading with William Friedkin and Nick Nolte, at Friedkin’s house. The scene was me knocking on Coach’s door; I didn’t like college anymore and I wanted to leave. I’d ask, “If I leave, will my mom lose her house and her job?” Kevin told me, “When you knock on the door and he says, ‘Come in,’ don’t go in right away. Wait for the second or third time he tells you to come in—you’re supposed to be apprehensive, afraid.” So I waited. And they hired me right away.

PARADA Billy thought he was the most natural actor he’d ever met.

Lastly: Ricky Roe, a country boy from French Lick, Ind., whose father asks coach Bell for a new tractor.

FRIEDKIN A lot of actors contacted me about playing [Ricky Roe]. Mark Wahlberg wanted it. I said, “I’m casting guys like Shaquille O’Neal and Anfernee Hardaway—can you play at that level?” Of course he couldn’t. I wasn’t interested in any of these guys winning Academy Awards. I was interested in authenticity of play.

REX WALTERS (actor, as himself) I read for the part of Ricky Roe, did a headshot. I also heard Bobby Knight wasn’t going to do the movie unless one of his players got a part. Now, this is all hearsay . . . .

MATT NOVER (center for Indiana; actor, Ricky Roe) I wouldn’t doubt that. He never told me that, but that’d be pretty cool.

FRIEDKIN Bobby never demanded it. He did suggest Nover. And the minute I met Matt—all you had to do was look at him. He was this All-American, Indiana basketball player. Physically, you could not do better for that role than Matt Nover.

NOVER I didn’t really grow up on a farm, but I had the crew cut, the clean Midwestern look of someone who did.

ROB RYDER (basketball coordinator) We weren’t really happy with Matt Nover. I certainly wasn’t. He wasn’t any kind of name player.

II. “OH, BOBBY, WHY YOU GOTTA BE LIKE THIS?”

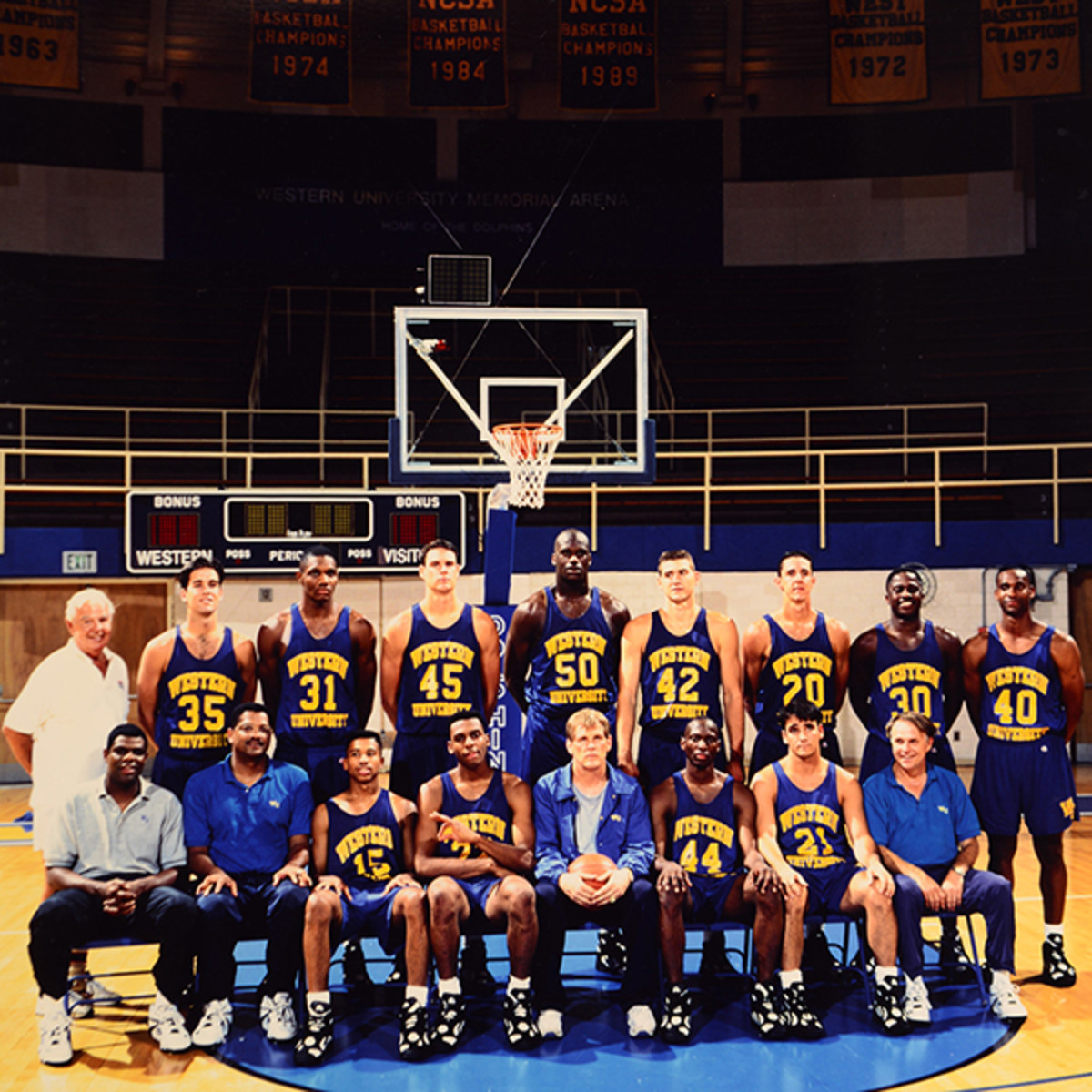

In the end, basketball roles largely went to basketball types: Producers cast 14 collegians who were about to be selected in the 1993 NBA draft; Friedkin doled out cameos to the likes of Larry Bird, Bob Cousy, Rick Pitino, Jim Boeheim, Jerry Tarkanian and George Raveling. And speaking parts largely went to seasoned actors: Ed O’Neill (then in Married . . . With Children) as a reporter; J.T. Walsh (A Few Good Men) as a villainous booster; Mary McDonnell (Dances with Wolves) as Bell’s ex-wife. The final cast, an odd mix of Hollywood and hoops royalty, created some memorable moments on set.

O’NEILL The first time I met Shaq I walked into the hair-and-makeup trailer; he was in the last chair and they were playing his rap album. They had it up loud. I said, “Turn this s--- off!” He looked at me, man . . . . He knew I was just kidding and he started laughing.

NOLTE Shaq used to come to my trailer and he would just shake the thing. I’d go to the door and all I would see was from his trunk down to his shorts, he stood so tall.

O’NEAL Nick has an acting switch like I’ve never seen in my life. He’d be talking with the boys, then as soon as they said “Action!” he’d turn into a different dude. Thespian-ism at its finest. I thought: I want to be that good. Wishful thinking.

CYLK COZART (actor, Slick the Fixer) Me, Shaq and a couple others went out [in Indiana] one night during filming, and they wouldn’t let Shaq into this club because he wasn’t 21. He goes, “I’m going to remember this when we play y’all.” That season, when he played his first game against the Pacers, he had like 35 points and 20 rebounds. [Editor’s note: 37, nine and four blocks.] He took it out on them because they wouldn’t let him in the club!

BENTON I remember Shaq saying to me that one day his jersey was going to be retired at the Forum [in L.A.], with all of those greats. The Forum was still open at that time. I remember thinking: You must be out of your mind. A few years later he was playing in L.A.

O’NEILL I really liked [Duke guard] Bobby Hurley. I’ll tell you a funny thing about that f------ Bobby Hurley. We were all so jealous of him. Every night of the week he was with another girl who was better looking than the night before.

HURLEY (actor, as himself) I got to meet Ed. He’s a big basketball guy. He was very popular from Married . . . With Children. It was a nice time. Good weekend.

O’NEILL I was sitting in a bar one night—it might’ve been after a big shoot. [Knight] wanted to meet me because he liked Married . . . With Children, apparently. One of his assistants came over and asked, “Do you want to meet coach Knight?” Sure. I sat down near him at a table, and he just nodded at me. I remember he was sunburned, because he’d been playing a lot of golf. Then one of his assistants said something like, “Coach Knight has forgotten more about basketball than most guys will ever know.” I’d had a few drinks, and I said, “How smart could he be—he had Larry Bird and let him go?” And the room went deathly silent. He just looked at me and smiled. He said, “Yeah, how smart could I be?”

The mood on set grew even more tense once cameras started rolling, in large part due to Friedkin’s extreme directing style.

RYDER What Bobby Knight was to coaching, Billy Friedkin was to filmmaking. He directed mostly through intimidation. I’ve never been on a set more stressful than Blue Chips.

NOLTE J.T. Walsh and I had a walking scene, quite a bit of dialogue, and J.T. didn’t have that dialogue down word for word, so by about take six Billy Friedkin said, “Goddamit, J.T., you haven’t learned your f------ dialogue. Jesus Christ, what the hell? You’re not here just to be good company. It’s work!”

RYDER It gets right down into your gut when he’s screaming at you. It’s like he becomes the devil incarnate.

FRIEDKIN Michael Mann, who directed Manhunter, asked me to play Hannibal Lecter. I thought he was crazy. He was like, “No, you’re very much like the way I see him.”

NOLTE Billy and I went nose-to-nose a couple of times. Once I came into the gym for a shot, and I was still eating a burrito. That really tweaked Billy. Little stuff, you know?

There was one moment where Friedkin may have crossed a line. The crew was in the UCLA dorms, filming a scene in which coach Bell confronts one of his players, Tony, played by Anthony C. Hall, after discovering Tony may have shaved points.

HALL Nolte and I rehearsed that scene over and over—with Friedkin too. He yells “Action!” for the first take, I’m giving him the scene exactly how we rehearsed it, and Friedkin busts in. “Tony, what the f--- is going on? Give me my f------ scene.” I’m wondering what he’s talking about. Take two, three, four, five, six, we do the exact same thing. Finally, on take seven Friedkin comes busting in again, screaming, “Tony, what the f--- is going on? Give me my f------ scene. Do you want to be a star? I love you; do you trust me?” I was like, “Yeah,”—but where is he going with all these questions? Then, Pow! pow! pow! He slaps the s--- out of me. I’m sitting there in shock. Nolte turns his back, like, Oh, s---.

NOLTE It was shocking.

HALL I want to hit this man, but this is my first job and I really don’t want to f--- up my opportunity in this business. I think I know where he wants me to go; I wish he’d just told me. I say, O.K., let me use this—but if he hits me again, I swear to God I’m going to tear this f------ dorm up. So he screams, “Give me my f------ scene!” and he walks out. “Aaand . . . action!” I gave him the emotional scene you see on screen, and he was happy.

O’NEAL After that he was One-Take Tony. I was like: Damn, Robert De Niro!

FRIEDKIN I got physical with Tony to get him focused and into the moment. It was a high dramatic point in the film. Nothing like that could happen today. You cannot physically touch [an actor].

HALL The first call I got that morning was from Sherry Lansing, [Friedkin’s] wife, who was the head of Paramount at that time: “Hey, Tony, I heard the scene went great last night. Is everything O.K.?” I said, “Yeah, I’m fine.” I’m thinking of all the things he promised—“You’re going to be a star after this”—and I’m thinking about suing Paramount. But as time has passed, I love William Friedkin.

Through all of Friedkin’s flaws, his cast and crew recognized his brilliance. His finest moment may have come on the day he filmed the movie’s climactic game—Western versus Knight’s fictional No. 1–ranked Indiana team—when the director defused a potentially disastrous situation. For that game, staged at Frankfort High, two hours north of Bloomington, thousands of locals filled the stands over four days to see Knight’s theatrical debut.

JOHNSON I didn’t see this; I heard about it. Knight was in wardrobe when Dick Vitale [who played himself in the final game] came up from behind and gave Bobby a bear hug. “Bobby! Bobby! Good to see ya!”

VITALE He was talking to some lady, upset about something. I went, “Stop complaining,” and I put him in a bear hug from the back. He turned around: “Oh, you’re just like all the other media!”

JOHNSON Bobby turned around and shoved Dick, who fell into a rack of clothes or a hamper.

FRIEDKIN He threw an elbow and freaked out.

O’NEILL This is what I heard: [Vitale] jumped on Knight’s back and Knight smacked him.

VITALE He turned and it looked like he pushed me, but he didn’t realize it was me. . . . I lost my balance—he’s a big, strong guy.

JOHNSON Bobby was like, “I had to put up with your s--- all season long; I’ll be damned if I’m going to put up with it during this film!” Dick was kind of hurt, like, “Oh, Bobby, why you gotta be like this?”

VITALE He said “I’m sorry” and all that jazz. He was just in one of his moods.

FRIEDKIN Now Bobby was not going to come out and do his scenes.

SHELTON Bobby was in a bad mood all day. One of his assistants said he’d had a bad day of golf.

FRIEDKIN He gave me a long story about how he was taken by surprise, he didn’t know it was Dick. But he was out of control; I don’t think he could help himself . . . . He had all of that bad publicity about throwing a chair, kicking his son—it had started to mount. And he didn’t want all of that out there. I told him, “I’ll talk to everybody involved and I’ll ask them to forget it.”

III. “THIS MOVIE AIN’T ABOUT YOU.”

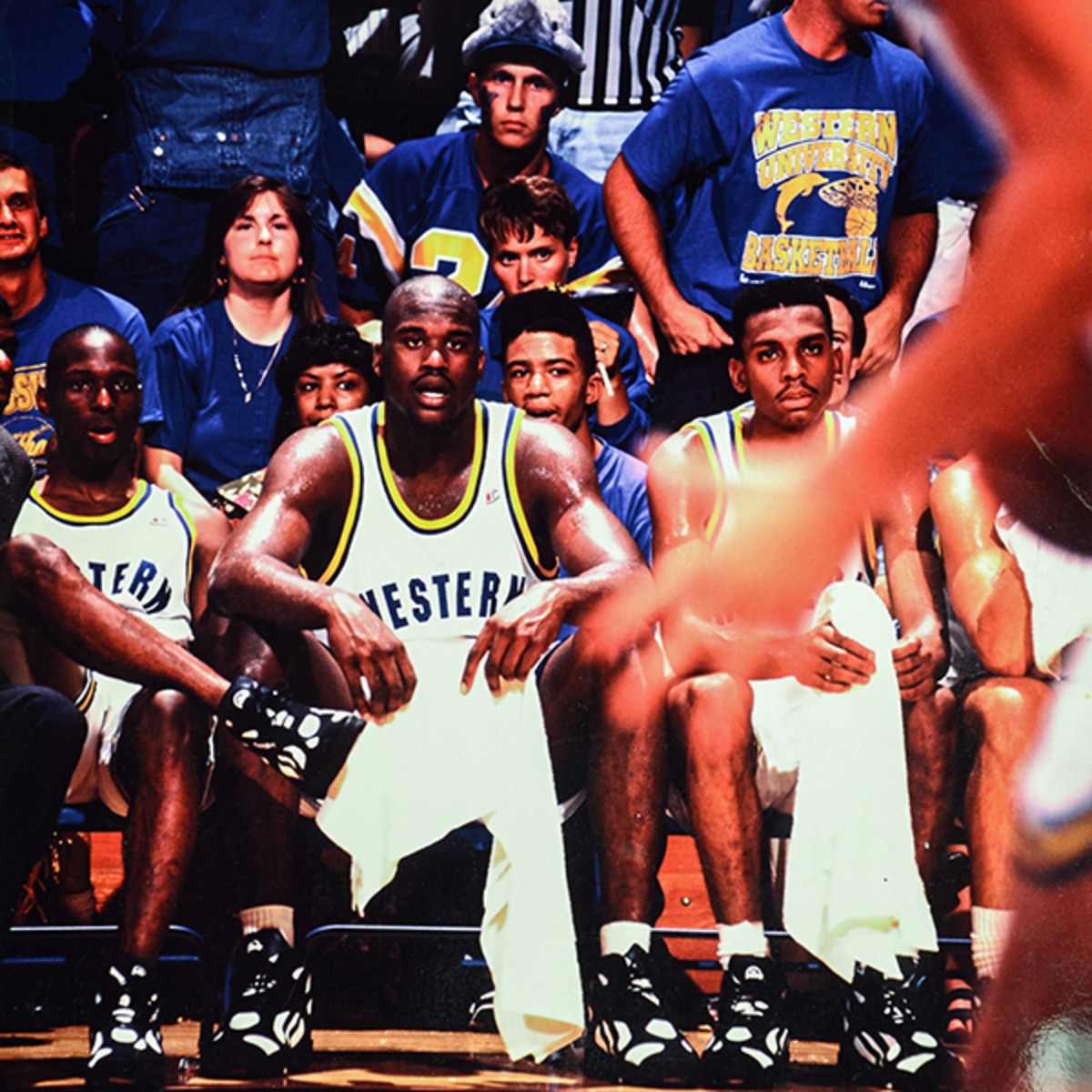

With Knight back on board, Friedkin could finally shoot his climactic game—actually two of them, edited later to fit the script, involving a slew of stars. On Western: Shaq, Penny and Nover. On Knight’s Indiana: Hurley, plus former Hoosiers Keith Smart, Greg Graham and Calbert Cheaney, the 1993 national college player of the year.

RYDER We were running real games, in real time, with a real clock, in front of 6,000 or so people.

NOLTE We put 17 cameras on those games.

O’NEILL I think they had 25 cameras running.

TOM PRIESTLY JR. (director of photography) No, no, no. We had five. Five cameras.

O’NEILL Bobby Hurley was on the Indiana team, and he was supposed to cover this actor coming down the court with the ball in one scene. [The actor] had said to me, “I don’t know about Hurley.” This guy had played pickup games at Venice Beach, and he was thinking: Bobby’s this white kid; I’m going to school this motherf-----. So they inbound to [the actor] and he starts down the court—and Hurley stole the ball from him, went down and laid it up. [The actor] took it out again . . . and Hurley stole it again, laid it up. Three times in a row. Finally, Friedkin said, “Bobby, let him bring the f------ ball down!”

HURLEY I really toned it down. When I usually played, I might throw some behind-the-back passes, some over-the-shoulder, some lobs. But Bobby’s teams played very fundamentally sound, nothing crazy. So I made sure I was as fundamental as possible.

HARDAWAY I knew that when the ball came I was going to cater to [Shaq], give him everything he wanted. I passed him the ball every chance I could.

CHEANEY It was like they’d been playing together for years—playing off one another, pick-and-rolls, lobs. . . .

O’NEAL I remember one game, all the extras thinking the movie was about them. I had to call a timeout. I said, “The next motherf----- that shoots, I’m punching him in the face. This movie ain’t about you. It’s about me and Penny.”

Which wasn’t exactly wrong. This was the summer of 1993, around the time of the NBA draft, when the Magic landed Hardaway to pair with O’Neal. Those two were set to become the next center-pointman supertandem—and, the way some people tell it, none of that would have happened without Blue Chips.

O’NEAL I didn’t know who Penny was before that movie. I was playing one day [in preproduction] and I noticed he was always on my team. I finally told somebody, “Man, I don’t know why this dude’s an actor. He can play in the league.” They was like, “He is going to play. He’s probably going top three in the draft.”

HARDAWAY We had some real basketball coaches on the set. Pete Newell [a Hall of Famer who passed away in 2008] was the Big Man’s coach. I was getting Shaq the ball in such good position under the basket, and when he was running the floor, that coach Newell was like, “You need Penny in Orlando with you, [Shaq]. He makes you look good!” I did that on purpose. That was intentional.

On draft night O’Neal’s Magic used their pick—the first in the draft—on Michigan’s Chris Webber. After the Warriors took Hardaway at No. 3, they shipped Penny and three later first-round picks to Orlando for Webber.

PAT WILLIAMS (Magic general manager) We came to the conclusion that the easy pick—the right pick—was Webber. He’d be paired with Shaq for 10 years. They wouldn’t make a lot of free throws, but they’d score a lot of points and grab every rebound.

O’NEAL I got on the phone to Orlando. I was like, “Listen: I don’t give a s--- which pick we get, we’re trading for Penny Hardaway.”

JOHN GABRIEL (Magic executive adviser) I know it’s been said [that Shaq lobbied us to draft Hardaway]. I don’t actually recall that. But I do recall knowing they were doing the movie together, that they were enjoying their time together, and that [O’Neal] thought very highly of how [Hardaway] played.

On set in Frankfort one week later, though, Shaq and Penny’s fictional Western team was losing to Indiana. Knight was coaching as if the climax of Blue Chips was the NCAA final.

CHEANEY We actually won both games that we played [for the final scene].

NOLTE And I had Shaq and Penny Hardaway!

NOVER I don’t think [Nolte] played much basketball growing up, so he didn’t understand the technical part of the game. You would see producers telling him, “O.K., in this timeout, here’s what you’re going to talk about . . . . ” Sometimes he’d get a few terms twisted. We’d be thinking, What exactly did he just say?

PRIESTLY I heard stories from the sound people. They had miked Bobby Knight [during the game], but they couldn’t use any of his dialogue because it was so full of expletives.

Regardless of the real-life score, Friedkin needed to stage a final play for the purpose of his movie. Someone would set a back screen for Shaq, who would roll to the basket for a game-winning alley-oop from Penny.

O’NEILL There are thousands of people [in the stands], and Friedkin comes out with a microphone to explain the shot to everyone. He says, “When the alley-oop goes up, I want everybody on their feet. The game will be over and your team will have won. I want everybody to storm the floor and go crazy.”

HURLEY In the huddle right before we’re about to go out, [coach Knight] tells us to grab Shaq—don’t let him get the lob pass. Then the director calls “Action!” I forget who grabbed Shaq, but the ball sailed out-of-bounds.

NOVER Coach Knight had the defender on the guy setting the screen just stand in Shaq’s way and not let him get the ball. They played it like coach Knight would’ve had us play it in a real game.

O’NEILL And Friedkin just sat there, like, I can’t f------ believe this.

JOHNSON Billy came over to us. “What happened?” We said, “You’ve got to talk to Bobby [Knight]." Bobby came strutting down. “Yeah, you’ve been screwing me this whole movie. Now I get a chance to f--- with you. I’ll let you make your movie. Run the play again.” We just looked at each other incredulously.

O’NEILL If Friedkin could’ve, he would’ve killed him—shot him to death.

FRIEDKIN It was not a gesture of evil. He just wanted to show everybody he’s not a loser. He told me, “I’m going to go out there and kick their asses—and then you can do whatever you want with that final scene.”

O’NEILL They reset it, Shaq slammed it in, and it was a happy ending.

HURLEY They stormed the court and you can see at the very end, Calbert Cheaney and I are kind of laughing, which would never happen after we lost a game like that. We won the game.

IV. “I GUESS BLUE CHIPS HAD IT RIGHT.”

When Paramount finally released Blue Chips in February 1994 the reaction was not fantastic. Critics panned the film for, among other things, the players’ poor acting (fair, mostly) and for the minimal screen time allotted to Shaq. Rotten Tomatoes gives it a score of 37%. But Blue Chips remains a cult favorite among a certain sect of sports fans, partly for its time-capsule feel, with all of its early-’90s basketball cameos, and partly because its story line still resonates.

SHELTON It’s very hard to be a college coach and be clean, to be honest. I think there’s a lot of hypocrisy in the world of college sports.

HARDAWAY (now the coach at Memphis) You see all the FBI stuff going on [with college basketball]. Of course, I haven’t encountered any of that. I guess Blue Chips had it right back in the day.

WALTERS (now an assistant at Wake Forest) I know that stuff exists to an even bigger extent today.

FRIEDKIN If you were going to do the film today you’d cast Zion Williamson.

SHELTON By the way: I’ve been trying to sell a TV series about this same issue—Can you be an honest coach and win?—set in the world of college football. And I’ve been unable to set it up. I think it’s as good as anything I’ve ever written.