Breaking Bad: The False Step and Downfall of Penn Legend Jerome Allen

On an afternoon in early June of 2013, Jerome Allen sat under a golden chandelier in the lobby of the Fontainebleau, the famously opulent hotel in the heart of Miami's Millionaires' Row, and waited for the man who had promised to change his life. It was around 4 p.m., and the room was sparsely populated, allowing the Penn basketball coach a clear view of the bronzed businessman with salt-and-pepper hair who soon approached.

Allen would remember how Philip Esformes, a health-care executive from Miami Beach, was holding two cellphones and a bulky plastic bag with drawstring handles. They had met once, earlier that year, and Esformes had told Allen that he was desperate for his teenage son Morris to attend Penn's Wharton School and play for the Quakers. If the coach could make that happen, Esformes had said, they would be "family for life."

Their discussion in the lobby didn't last long. Allen confirmed he would watch Morris, a 5'8" guard, work out later that day. Esformes asked him to please call when the session was over; he was eager to hear the coach's thoughts. Then, without explanation, he extended the bag toward Allen.

At that moment, Allen had a sterling reputation within basketball. His life was an inspiration to many: He had risen from the North Philadelphia projects to become a star point guard at Penn, the Ivy League player of the year in 1992 and '93. After two seasons in the NBA he embarked on a successful career in Europe, then returned to his alma mater to coach. Over the years, he had earned renown for his work in the community, supporting and inspiring a generation of inner-city kids.

Allen took the bag. Then he returned to his hotel room, alone, and emptied the contents: a shoebox filled with $10,000 in cash.

Six years later, Allen found himself on a witness stand in federal court just eight miles from the Fontainebleau, detailing that day and the two-plus-year relationship with the Esformes family that followed. He was there as a cooperating witness for the government, testifying against Esformes, who had turned out to be the mastermind of the largest Medicare fraud scheme in American history.

Facing the possibility of 10 years in prison, Allen explained how he was guilty of bribery, wire fraud, money laundering and tax evasion; how Esformes had paid him more than $300,000 on top of hotel accommodations, airline flights, concert tickets and sneakers; how he broke both NCAA rules and federal law to get Morris into Wharton, one of the country's most prestigious undergraduate business programs, by claiming, falsely, that he was a prized basketball recruit.

After the second day of Allen's testimony in March, Judge Robert N. Scola instructed the jury not to watch the news that night. There would be a story breaking, the judge said, about a case strikingly similar to theirs.

The case he spoke of turned out to be the biggest college admissions scandal in history. Fifty people were accused of paying as much as $25 million in total from 2011 to '18 to get their children into elite colleges by faking standardized test scores and paying off school officials. In what became known as the Varsity Blues scandal, coaches were bribed to pass off applicants as recruited athletes even though they weren't skilled enough or, in some instances, had never even played their supposed sports. The 33 parents charged, including actresses Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin, received the most attention and opprobrium—the rich and famous robbing deserving students of coveted opportunities.

But what about the nine coaches charged, the ones who confronted the very decision that Allen faced when Esformes held out that bag? Allen's story—told here with the aid of court transcripts and exhibits, financial records, news reports and interviews with three dozen of his friends, classmates, teachers, coaches, players, mentors and coworkers, many speaking anonymously for fear of personal and professional ramifications—provides a case study.

Allen, 46, would say in court that financial problems led him to reach out and take the bag from Esformes. But the question of why Allen ended up entangled in a scandal that seemingly went against everything he stood for is more complicated.

There's a story that Allen likes to tell about his childhood. It starts with how he grew up in Philadelphia's Germantown projects, living with 18 relatives in a five-bedroom house. He shared a bed with his sister until he was 15 and watched an aunt and uncle sell crack out of their home. Allen's father was an addict and left when his son was 10; his mother, a hotel maid, raised him. While Jerome had always flashed athletic promise, he was on a wayward path. At 13, he showed up to a basketball practice drunk.

One day in eighth grade he was hanging out at the Gustine Recreation Center in the East Falls projects and sneaked into the coordinator's office. But rather than pilfer items—like Ping-Pong balls or cans of soda—as he often did, Allen sat down and began his math homework. When the coordinator walked in, he started to yell. But then he realized what Allen was doing, saw potential and made some calls. "That one particular time, that interaction," Allen said in court, "led to me having an opportunity to go to the Episcopal Academy."

When Allen arrived at the prestigious private school, he encountered classmates, nearly all white, with nice cars and nice clothes and fridges full of food. At Allen's house, there was no heat, the lights were rarely on, banisters were falling apart, and the only item in the fridge was fruit juice, friends recall. During hot summers he slept with a cold washcloth on his head. Whenever he got a ride home, he asked to be dropped off on a different street.

At first Allen was bitter about his schoolmates' privilege. But soon he recognized the opportunity he had been given, friends say, and adapted, becoming friendly with jocks and theater geeks alike. He hung out at their homes and got summer jobs at their parents' companies. He stayed out of trouble and spent all of his time in study hall or on the basketball court, growing from a freshman who didn't make varsity into one of the best guards in the country. "He was as great a person that you could be," says Gina Buggy, the school's longtime athletic director.

Sixteen programs in all, some of them in top conferences, offered Allen scholarships. Instead, he chose to play for Penn coach Fran Dunphy. Back then, Allen wanted to be an accountant; a Wharton degree, he knew, would enable him to find a job and support his mother.

Allen led the Quakers to three straight Ivy League titles and a 48-game conference winning streak, which remains a record. He forged a reputation for being humble, thoughtful, soft-spoken—so much so that reporters struggled to capture his voice on their recorders. Teammates describe him as intensely focused and disciplined. "Just determined for greatness," recalls former teammate Ken Hans.

On campus, Allen was revered. He was stopped so often, and became so engaged in every conversation, that friends say a 10-minute walk across campus took an hour when they traveled with the man some took to calling the Mayor.

But Allen said little about his difficult upbringing to classmates and the media. He did confide in some teammates, like Cedric Laster, who played with Allen for three seasons. The two discovered luxuries they had no idea they lacked, like summer homes. "Being at Penn was opening the door to a whole new world that you on your own wouldn't have access to," Laster says. As another of Allen's confidants at the time puts it, "When you come from where he came from, and see all these kids at Penn, for him it was like, Why can't I have that?"

Allen did his best to give back, tutoring in West Philadelphia and inviting teens from his old neighborhood to visit campus. When the Timberwolves selected him with the 49th pick in the 1995 NBA draft, he was able to do more. Earning the league minimum of $200,000, he would claim that he supported 15 family members and friends—a number of those who know him say was not hyperbole. He did have personal indulgences—including a Range Rover and a Mercedes CL 500 Coupe—but one NBA teammate remembers that whenever Allen passed a homeless person on the street, he would hand over a $50 bill.

After two seasons in the NBA, Allen moved overseas; for more than a decade he played in France, Turkey, Greece and Italy, developing a taste for slim-cut suits. During summers he would return to play in Philadelphia's famed Sonny Hill League, one of the few older players who had time for the younger kids in the crowd. In 1999, Allen founded an organization called H.O.O.D. (Helping Our Own Develop) Enriched, a basketball and tutoring program for underprivileged teens. He often shared his story, stressing the importance of education. Over the course of three summers, Allen says he spent $400,000 to take 36 kids to Italy, where they played local teams, ate gelato and pizza, and saw a world far removed from their own.

"He gave us hope," says Mike Jordan, a Philadelphia native who would go on to star at Penn. "I looked at his example as a way for me to do the right things."

When Allen retired from playing in 2009, he returned to the school where he was idolized. He enrolled in the four classes he needed for his degree and joined Glen Miller's staff as a volunteer assistant, hoping to launch his own coaching career.

After the first seven games of that season—all losses—Miller was fired and Allen was promoted to interim coach, despite his lack of experience. He finished out the season 6-15, but Penn gave him the permanent job anyway, hoping he would invigorate fans and revitalize fund-raising by bringing back, as one person connected to the program puts it, "the Jerome Allen magic."

"But it was unfair to Jerome," the person continues. "He was not ready."

Allen's coaching style was tough. Practices were long and demanding, and he would often berate players for mistakes. Some left the program. But those who stayed profess love and admiration for Allen, many calling him a father figure.

Every Thanksgiving the coach would bring his players to a soup kitchen to feed the homeless, and then host them for dinner. His wife, Aida, whom he married when he was playing overseas, would cook turkey and stuffing, ziti and corn—and Allen would instruct his players to say please and thank you.

He made sure they always dressed appropriately and took off their hats at team meals; he helped with mock job interviews, introduced them to notable alumni and taught the importance of punctuality, eye contact and a firm handshake.

Says Rob Belcore, who played three seasons for Allen, "I am seven years in the working world, and I've never showed up to any meeting anything other than early."

Yet on-court success never came. And while Allen never admitted it, many around him say they could sense a number of stresses weighing on him. His salary reached more than $270,000, but he often alluded to financial strains. He would lament that he was sending his three kids to private school and had to worry about saving for college. The undercurrent: What would happen to his family if he were fired?

He spoke with a friend about what it was like when he went back to visit his old neighborhood. The friend sensed that Allen never felt fully removed from that life, despite all of his achievements. "It was never enough for him," the confidant says. "He straddled the line sometimes between one life and another."

At Ivy League schools, where ticket sales and TV contracts bring in a fraction of what they do at bigger programs, fund-raising is a major responsibility for coaches. During Allen's tenure the administration would often implore him to court donors. In his 2014 year-end review, Allen was told that he needed "to keep and maintain strong communication with the alumni for development purposes." So he spent hours at Penn fund-raisers, working alumni inside stately Main Line houses and at backyard barbecues.

According to several associates, while Allen was adept at that aspect of the job, he never felt accepted as a member of that world. The coach often reminded his players of his humble background, saying, "I'm just a black man from Germantown." And whenever a player flashed his family's affluence—a nice car, the mention of a vacation overseas—Allen joked that he'd like to see some piece of it, often repeating the phrase: "Let me hold some money."

There were other financial stresses Allen didn't share. In the late 1990s, during his playing career, he faced a series of civil suits over unpaid debts—$5,000 owed to a car-leasing company, $13,000 to a bank, $6,700 to a landlord. And in 2011, while Penn employed Allen as its coach, the school sued him for nearly $25,000 for failing to pay off two decades of accrued interest on a loan he had taken out as a student.

In his testimony Allen often mentioned the importance of his education—not just for him but for his "family's trajectory." He viewed going to a good private school and an elite college as his salvation, and he wanted to give his children the same opportunities. So as he was shelling out large sums to ensure their futures, he was failing to pay $48,535 in federal income taxes, leading to an IRS lien in '13—the same year he met Philip Esformes in a hotel lobby and was handed a plastic bag.

It started as a favor to an old friend, Mike Penberthy. The two had been teammates for four and a half years in Italy and, as Allen would say in court, he considered Penberthy "almost a brother."

Penberthy called Allen in early 2013; he said that Esformes was regularly flying him from California to Florida and paying him $7,000 a weekend to train his two sons. Penberthy asked if Allen would come to Miami to watch the older kid, Morris, play; Allen said if he were ever in the area, he'd stop by.

Shortly after Allen's third full season as coach ended with a disappointing 9-22 record, he found himself about an hour north of Miami on a recruiting trip. The coach met Penberthy and two other trainers at the JW Marriott Marquis, where Philip had rented out the 19th-floor basketball court. After watching Morris work out, Allen didn't view him as a potential recruit, the coach would later say under oath.

Once the workout was finished, though, Allen went back to the Esformes's $4.5 million estate—lined by palm trees and with a full court in the back—to meet Philip for the first time. There, Esformes told Allen it was his dream for Morris to play basketball at Penn and go to Wharton. "Family for life," he promised the coach.

Not long after, Esformes flew Allen back to Miami, paying for a limo from the airport and a room at the Fontainebleau. He reiterated that he was going to take care of the coach and his family. That's when Esformes handed over the plastic bag and their mutually beneficial relationship began.

Nearly every month after that meeting, Esformes flew Allen to Miami and put him up in the same hotel. Each time, Allen trained Morris or simply watched him work out, then received a bag of cash. In July 2014 the payments became wire transfers. The amounts varied—$5,000 sometimes, $20,000 other times—but every month they came. "I took whatever he gave me," Allen would say in court.

Over the course of two and a half years, their relationship grew. They developed nicknames for each other—Oldhead and Youngblood—and frequently ended text messages with "love you." Their families became close; Esformes often flew Allen's oldest son, Jerome II, to Miami, where he stayed at the estate, sometimes for as long as a week, and Allen's daughter interned at one of the executive's medical facilities. He invited Allen to tour a detox clinic and allowed him to sit in on a meeting. Esformes even talked of bringing the coach into the business.

Allen frequently told Esformes how much he respected him as a man and as a father. He also developed a bond with Morris, who suffered from scoliosis and whom Allen described in court as having significant confidence issues. After all, Morris's guidance counselor at Hebrew Academy in Miami Beach had expressed skepticism about his chances of playing college basketball; his own grandfather had even told him he'd never be a Division I athlete. He received ridicule on social media and in the comment sections of his highlight tapes. "I saw this kid play and I can't stop laughing," one read. "He is terrible."

It was easy for Allen to get Morris admitted into Wharton—just as it was for the other coaches involved in similar schemes. While Ivy League coaches cannot offer athletic scholarships, they do create priority lists for the admissions office. All Allen had to do was list Morris as one of the team's five recruits. There was no further oversight. As Alanna Shanahan—Penn's associate athletic director at the time—testified in court, "I have to have basically total trust [in the coach]."

Players on that priority list are "99% likely" to be admitted, Shanahan said, as long as they are above the Academic Index (AI) floor. AI is a ranking unique to the Ivy League, incorporating GPA and standardized-test scores, with all teams required to hit a certain threshold. It is no secret that Ivy League coaches, in every sport, manipulate the AI. Often, mediocre players with high grades are recruited simply to balance out the team's index. In one year-end review, the athletic department admonished Allen for his recruits' lack of "academic ability."

Morris helped with that: buoyed by a 1920 on his SATs (out of 2400), he had an AI score of 211, the second-highest for any recruit in Allen's tenure as coach. But, Allen said in court, he could have found a better player with the same AI "from anywhere in the country." Allen also gave Morris one of the team's two Wharton spots that year, which Penn coaches often use to lure their most prized recruits.

In retrospect, Morris's SAT score may have been suspect, too. During Allen's trial it was revealed that Esformes—who in April was found guilty on 20 charges in the $1.3 billion Medicare scheme (although no verdict was reached on the charge of conspiracy to defraud Medicare) and is currently being held without bond while awaiting sentencing—donated $400,000 to the now-disgraced foundation of Rick Singer, the man alleged to have orchestrated dozens of bribes to coaches and faked test scores as part of the admissions scandal that engulfed Loughlin and Huffman. Court exhibits show that Esformes, who did not reply to multiple requests for comment, texted Singer about Morris's SAT score and discussed a testing site in Arizona where results could potentially be doctored. Prosecutors did not discover why Esformes donated the money. And while Singer also funneled bribes to coaches, there's no evidence he was involved with Allen.

As Allen and Esformes's relationship progressed, the coach began to bring four of his players down to Miami with him, Quakers who had rough backgrounds similar to his own. They'd stay at the mansion, hang out and play basketball with Morris—often at the two-story facility Philip had built down the road, replete with an indoor court, weight room and kitchen. At times Allen ran them through what amounted to a typical Penn practice.

This became a somewhat open secret among the Quakers. Still, Allen feared their agreement was getting too public. He often pleaded with Esformes to tighten his circle.

In court, Allen recalled being alarmed when one of his assistants at Penn asked why he was in Miami. Another time, an acquaintance in Los Angeles said he knew that Esformes had given Allen the pair of Air Jordans he was wearing. Then Martin Fox—a Houston AAU coach who would later be arrested in the larger admissions scandal and charged with conspiracy to commit racketeering—offered Allen $100,000 to help get another kid into Penn. Allen declined. "This wasn't my thing," he would claim in court.

Allen appeared to view his agreement with the Esformes family as a justifiable exception, a relationship that could benefit everyone. After all, wealthy donors regularly buy their kids' way into schools. "Jerome thought if he got in good with [Esformes], that he'd be a person who'd help us fund-raise," says a source formerly inside the program. "That's a relationship the university would want him to make."

Only once during his two days of testimony was Allen directly asked by prosecutors why, "after playing for the University of Pennsylvania, after serving as the head coach, did you decide to be dishonest to your school?"

"I lied," Allen responded. "I accepted the money to help Morris Esformes get into school." He did not provide any further explanation.

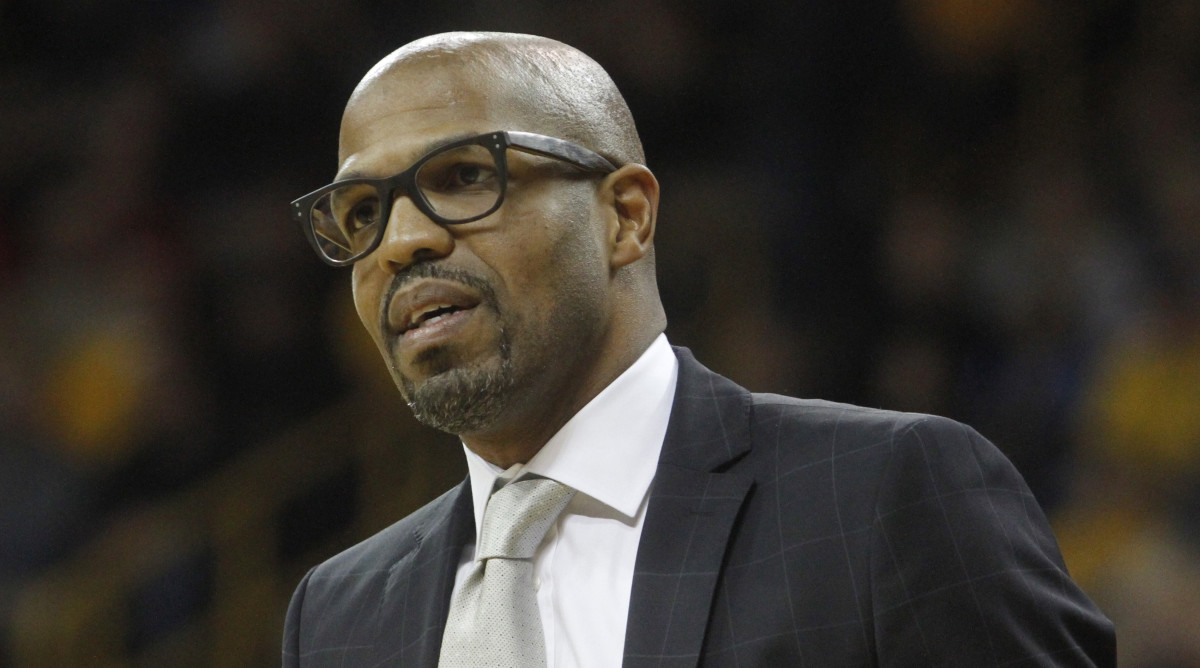

Two months after testifying, Jerome Allen stands near center court at the Celtics' practice facility, chewing gum and wearing a black tracksuit. It's early May, eight hours before Boston's Game 3 Eastern Conference semifinal matchup against the Bucks, and Kyrie Irving, Jayson Tatum and Terry Rozier surround Allen, all engaged in a shooting competition. He is beloved by the players—forward Marcus Morris called him "the backbone coach of the team."

Boston hired Allen as an assistant in July 2015, four months after Penn fired him with a 66-104 career record. When Allen was let go, he testified in court, Esformes wanted assurances that Morris—finally about to enroll—would still make the team. He asked Allen if he could pay Penn assistant Ira Bowman, the only coach on staff who knew about their agreement. Allen and Bowman had played together at Penn; Bowman had even lived at Allen's mom's house one semester. So Allen set up a separate account and whenever Esformes wired the monthly payment, the coach transferred part of it to Bowman.

Last July, Allen was charged and quickly cut a deal, agreeing to testify in the bigger Medicare fraud case against Esformes and pleading guilty to money laundering and wire fraud. The Celtics suspended him for two weeks. After Allen revealed his friend's involvement this March, Bowman, by then an assistant at Auburn, was suspended indefinitely.

When Allen is approached after practice in Boston, standing off to the side of the court, he says he might be willing to speak, but will have to talk to his lawyer first. Later, he'll decline.

"Jerome was forthright, accountable, and contrite in discussing the mistakes he made prior to becoming a Celtics employee," a team spokesperson said. "We believe he has learned from the situation, and we appreciate all Jerome has done in his time with our organization."

In March, Rudy Meredith, the former Yale soccer coach who resigned after being implicated in the Varsity Blues scandal, pleaded guilty to fraud and conspiracy, agreeing to pay back $866,000 and to serve 33 to 41 months in prison.

Allen, though, avoided jail time. Prosecutors had recommended four months in prison on account of Allen's "substantial assistance" in the case against Esformes. But at his sentencing on July 1, U.S. District Judge Kathleen Williams gave Allen four years' probation, including six months of house arrest along with 600 hours of community service, and ordered him to pay a $202,000 fine and an $18,000 forfeiture judgment to the U.S. government. (The coach earns a $350,000 salary from the Celtics.) House arrest sentences often include allowances for working outside the home, and a team source said that Allen's shouldn't affect his status with the team.

Before sentencing, a stream of Allen's former teammates, coaches and players urged the judge for leniency, testifying to Allen's "true character," his work in the community and his years shaping the lives of young men. Allen himself gave a statement, mentioning his financial issues, explaining how he believes the scandal has made him a better person and thanking God for "expanding" his "platform" to help reach more young people.

"I will spend the rest of my life living up to the ideals that we, as a family, espouse," Allen said in a statement last October. "My family means everything to me. Regrettably, I have earned their disappointment. While I cannot undo the past, I can be a better man in all my future interactions. That is my promise to them."

During his two days on the witness stand, Allen frequently referred back to another promise: the one Philip Esformes made during their first meeting, before he handed him that plastic bag. After Morris arrived at Penn and began practicing with the team, Allen's replacement, Steve Donahue, told him he wasn't going to make varsity. So in September, Morris quit, and the wire transfers stopped. Allen testified that he felt betrayed; he thought he still deserved the payments, even though he'd said repeatedly that he knew they were wrong. "What does 'family for life' mean?" he asked the court in a rare moment of defiance, seemingly breaking from the script.

The coach admitted that, yes, he lied to his supervisors, he lied to the admissions department and to his staff and even to his wife on numerous occasions. He put his "whole career out there," he said. But the one thing he couldn't abide, he testified, is when someone swears he is going to take care of him, take care of his kids, and he doesn't honor that promise—maybe that was just the "North Philly in me," he said.

"But at the end of the day, I hold myself accountable," Allen continued. "Because I did it, I said yes, I created this storm. It's my fault, because I could have said no."