Revisiting Details of the Lorenzen Wright Case and Questions That Remain

Nearly nine years to the day Memphis police cadaver dogs discovered the decomposed and bullet-riddled corpse of former Memphis Grizzlies center Lorenzen Wright, the player’s ex-wife, Sherra Wright, pleaded guilty to charges connected to the murder.

Last Thursday, the 48-year-old ordained minister acknowledged to Shelby County Judge Lee Coffee that she is guilty of both facilitation of first-degree murder and facilitation of a criminal attempt to commit first-degree murder. Wright’s plea is part of a deal arranged between her attorneys and Shelby County prosecutors, who had intended to bring Wright to trial in September.

Judge Coffee sentenced Wright to 30 years in prison. In light of time already served and parole eligibility, it’s possible that Wright could be released as early as 2026. Had Wright gone to trial and been convicted of first-degree murder, she faced the prospect of spending the rest of her life behind bars.

The murder of Lorenzen Wright perplexed law enforcement for years. In 2015, SI executive editor Jon Wertheim expertly detailed the investigation in his Sports Illustrated feature story, Who Killed Lorenzen Wright? Wertheim’s story was part of a Sports Illustrated and Fox Sports 1 collaborative investigation, which included a memorable video interview with Wright.

During the interview, Fox Sports producer Matt Schlef asked Wright a straightforward, yes or no question: “Did you have any part in Lorenzen’s murder?”

Instead of answering “no,” Wright paused and offered a suspiciously evasive and non-responsive remark. “At first,” Wright replied, “I’m a wife, then I’m a mother, and then thirdly I’m an author. The law enforcement should do what’s best to find out who’s the killer.”

Law enforcement eventually did “find out who’s the killer.” It was Sherra Wright, along with others.

The rise and fall of the Wrights—and their money woes

Lorenzen Wright’s rise to fame, and his relationship with Sherra, are expertly detailed in Wertheim’s feature story.

As Wertheim explains, Wright was a basketball prodigy from early in his life. He would star at Booker T. Washington High in Memphis. A McDonald’s All-American, Wright earned a spot on the 1994 Parade All-American Second Team. Wright also met his future wife while in high school. Sherra was the daughter of Wright’s AAU coach, Julius Robinson.

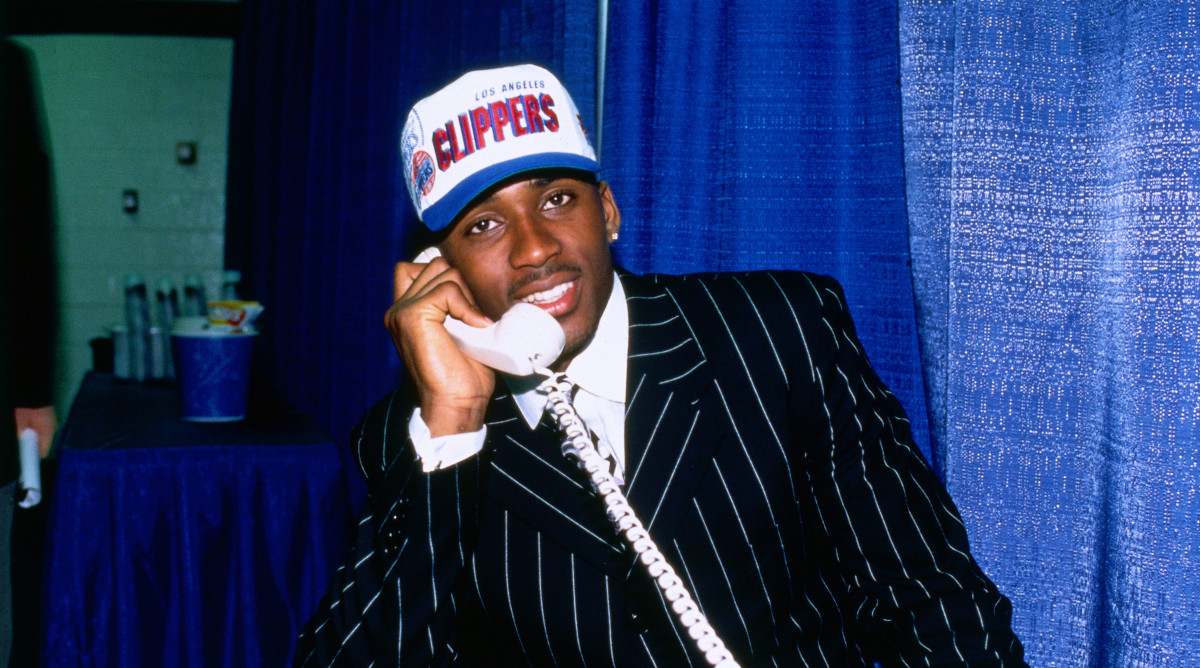

Major college programs from across the country recruited Wright, but the 6’11" center remained local by enrolling at Memphis State (later renamed the University of Memphis). Wright played two seasons at Memphis and averaged 16 points and 10 rebounds per game over those two seasons. The Los Angeles Clippers drafted Wright with the seventh overall pick in the 1996 NBA Draft.

Although never a star in the NBA, Wright was a reliable big man who started most of the 793 regular season and playoffs games in which he played. His best season occurred in ’01-’02 when he averaged 12 points and nine rebounds a game. Wright’s career would end after the ’08-’09 season when he was unable to land an NBA contract.

According to Basketball-Reference, Wright earned $55.2 million over his 13 seasons in the league. Despite amassing such wealth, Lorenzen and Sherra were in financial distress by the time his NBA career had ended. A bank sought to repossess his home in Atlanta and the couple owed money elsewhere. They also had six children to raise.

Financial woes were likely contributing factors in Lorenzen and Sherra’s decision to divorce in February 2010. They had separated several times and reconciled. However, after 13 years of marriage, they decided to enter new chapters of their lives.

The money problems would only worsen after the divorce. Lorenzen fell behind on paying child support and maintenance (alimony). Sherra would later insist that Lorenzen had affairs with multiple women and had been abusive to her and her children. She also said he had business dealings with persons who had ties to drugs, though Wright himself was never implicated in criminal activity.

The murder

On Sunday, July 18, 2010, Wright was visiting Memphis from his home in Atlanta to see his children. His visit included a chance to watch his teenage son, Lorenzen Jr., play basketball. That evening Lorenzen Sr. visited his ex-wife at her house in Collierville, Tennessee. Sherra later told police that Lorenzen would leave her house with another person, whom she did not know, and that they drove off in a vehicle she did not recognize. She also recalled that Wright was carrying a box full of drugs and that he was holding a considerable amount of cash (Wright later recanted the depiction of the box as full of drugs).

Shortly after midnight on July 19, Wright used his cell phone to call 911. He spoke briefly with a dispatcher in Germantown, Tennessee. His whereabouts were unknown at the time and Wright was unable to relay logistical information—he screamed the phrase “Hey God damn” as the repeated popping sound of gunshots were heard, followed by silence.

Wright was only 34 years old.

Based in part on shell casings later recovered from the crime scene, police determined that two different guns were used to fire between nine and 11 bullets at Wright. The former basketball star died instantly as he was shot twice in the head, twice near his heart and once in the forearm. Inexplicably, the 911 dispatcher neglected to inform a supervisor about this disturbing call. This led to a delay in the reporting of the crime and an accompanying delay in the discovery of Wright’s body.

Hours after the shooting, a neighbor of Sherra Wright noticed a perplexing event in Wright’s backyard. Wright and an unidentified male ignited a bonfire. It was a strange occasion to have a bonfire. According to Weather Underground, the temperature in Memphis that summer day reached 93 degrees and, with a dew point of 73, it was also quite muggy.

Three days later, Wright’s mother, Deborah Marion called the police to express worry that neither she nor any other family members had heard from Wright. This prompted a multi-day investigation, which included interviews with persons who had last seen Wright. Sherra Wright was thus a key witness and her home was searched pursuant to a warrant, though police did not find probable cause to charge her.

Wright’s decomposed body was found on Wednesday, July 28 in a remote area near the TPC Southwind golf course. By the time it had been discovered, Wright’s 260-pound body had been exposed to intense heat, rain and animals. It had shriveled to just 57 pounds.

The shooting did not appear to be connected to a robbery gone wrong. Wright was still wearing visible and expensive apparel, including a gold necklace and a watch. The shooting was consistent with a deliberate attempt to take Wright’s life.

The insurance policy, Wright’s pension and the fight over money

The criminal case essentially went cold for the next seven years.

Sherra Wright nonetheless raised suspicions. In addition to the oddly-timed bonfire and her unusual responses in the SI/Fox Sports interview, Wright’s handling of money proved alarming. This was particularly apparent in regard to a $1 million life insurance policy that Lorenzen had purchased as a condition of their divorce settlement. The policy was paid a year after Lorenzen’s murder. The wait was to be expected given the criminal circumstances of his death and suspicions about Sherra Wright.

The insurance policy was not for Sherra Wright’s benefit. It was intended to benefit their six children, with Wright designated the policy’s administrator on behalf of her children. Within months of receiving the $1 million, Wright had spent all but $5.05. She spent the majority of the $1 million in ways that appeared only loosely connected to her children’s well-being. For instance, she used it to buy a house, purchase expensive furniture, acquire multiple luxury cars and finance vacation travel.

Worried by Sherra Wright’s rapid spending of money that her ex-husband had intended to provide long-term benefit their children, Herb Wright—Lorenzen’s father and the executor of his late son’s estate—sued Sherra Wright on behalf of his grandchildren. A Tennessee circuit court resolved the matter by ordering the creation of a trust intended to benefit the children. Sherra Wright was named the trustee, but with the stipulation that she file with the court regular accountings of money received by the trust and money paid out.

The insurance policy was not the only sizable sum designated for the trust. Under the collective bargaining agreement between the NBA and the National Basketball Players’ Association, Lorenzen Wright became vested in pension benefits after playing three seasons in the league. Court records obtained by Sports Illustrated show that the NBPA owed approximately $184,000 as a death benefit. This amount was to be paid into the trust.

Those court records also revealed that Sherra Wright had failed to provide accounting statements to the court. Sherra Wright later withdrew from an effort to maintain control of the trust. A probate judge declared Herb Wright the guardian over the pension funds. Sherra Wright and Herb Wright also reached an out-of-court settlement to resolve related matters.

At around this time, Wright became more active in her local church, Missionary Baptist Church. She was ordained a minister. Wright also married a local sheriff’s deputy named Reginald Robinson.

Wright further raised suspicions by authoring a supposedly fictional book. In “Mr. Tell Me Anything,” Wright envisions a world that seems eerily similar to one that she had lived and perceived. The book, which was published in 2015, centers on the life of a woman who marries a basketball star. The husband is unfaithful and abusive.

During that same year, Wright relocated to Houston, Texas, with a new boyfriend, Kelvin Cowans, and her children.

A year later, Sherra Wright brought new litigation against Herb Wright. She insisted that the trust, under Herb Wright’s control, owed her money. She claimed that her late husband had failed to make child support and alimony payments and that those amounts ought to be paid out of the trust.

A Tennessee Circuit court rejected Wright’s petition on account of the legal principle of res judicata, which is a Latin expression that means “a thing decided.” In law, res judicata instructs that once a legal claim has been resolved, it can’t be re-litigated. Here, Sherra Wright and her former father-in-law had resolved the matter in their 2015 settlement. Sherra Wright appealed to the Court of Appeals of Tennessee, but a judge sustained the decision in a ruling in May 2017.

That same year, Wright relocated her family to southern California. In California, Wright married a man named Tim Robertson. Fox 13 identified Robertson as working for a record label and having lived at one point in Memphis.

Sherra Wright is arrested

The fall of 2017 was also extremely eventful in the murder investigation. On November 10, a gun was recovered from a lake in Walnut, Mississippi—about a 45-drive from Sherra’s Wright former home in Collierville. Ballistics linked the gun to the bullets fired into Lorenzen Wright. Three weeks later, police in Collierville arrested Billy Ray Turner, a 48-year-old church deacon and landscaper with a criminal record, for the murder of Wright. Four days later, Sherra Wright was arrested in California, also on murder charges.

Sherra Wright and Turner had known each other for some time. They had also allegedly conspired on two attempts to murder Lorenzen Wright. The first occasion was in Atlanta, but it failed. The second time was the (gruesomely) successful attempt in Tennessee. A third person, Jimmie Martin, is also believed to have played a role in Wright’s murder. Martin, who is incarcerated on a separate murder conviction, is a cousin of Sherra Wright. He reportedly revealed to police the location of the gun.

While Wright’s criminal case is resolved, Turner is scheduled to go to trial for Wright’s murder in September. It is unknown if Sherra Wright has agreed to testify against Turner—who has already pleaded guilty to a gun charge in the case—as part of her plea deal. However, a commitment to offer such testimony would be a logical demand from prosecutors.

Lingering questions

As time goes on, the murder of Lorenzen Wright and its subsequent legal fallout will raise questions about how life insurance and player pension policies that are intended to benefit a player’s heirs ought to be administered. These are questions that financial planners who design such policies will consider. In this situation, a battle over money spawned a multi-year legal battle between relatives who claimed to be looking out for the best interests of Lorenzen Wright’s children.

While Sherra Wright has not admitted to avarice motivating her to partake in the planned murder of her ex-husband, it is plausible, if not likely, that greed played an instrumental role. Her hasty and imprudent spending of the $1 million life insurance policy, along with her former father-in-law’s legal efforts to prevent her from squandering $184,000 in benefits from Lorenzen Wright playing in the NBA, highlight the challenge of ensuring that money goes to where it is intended.

Michael McCann is SI’s Legal Analyst. He is also an attorney and Director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law.