She Won Athletes' Hearts. And Robbed Them Blind

This story appears in the Sept. 23, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated.For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

On the morning he learned his bank account had been drained, Rashad McCants couldn't afford doughnuts. As a rookie at Timberwolves training camp in the fall of 2005 it was his duty to snag a couple boxes of breakfast treats before practice, as assigned by the team's unquestioned alpha, Kevin Garnett. So when the 21-year-old guard reported to the locker room empty-handed—unable to cover even a single cruller—he got blasted with a KG earful. "No way you don't have money," McCants recalls Garnett barking. "I'm not trying to hear that s---!"

McCants was baffled too. Six months after leading North Carolina to the NCAA title as a junior and declaring for the NBA draft, at which the T-Wolves took him at No. 14, he'd just received the first check from his $1.54 million rookie deal. Even after some admittedly lavish splurges, though—a Range Rover, a $5,000 Brioni suit and various Louis Vuitton items—he knew there was no chance he'd already blown through six figures.

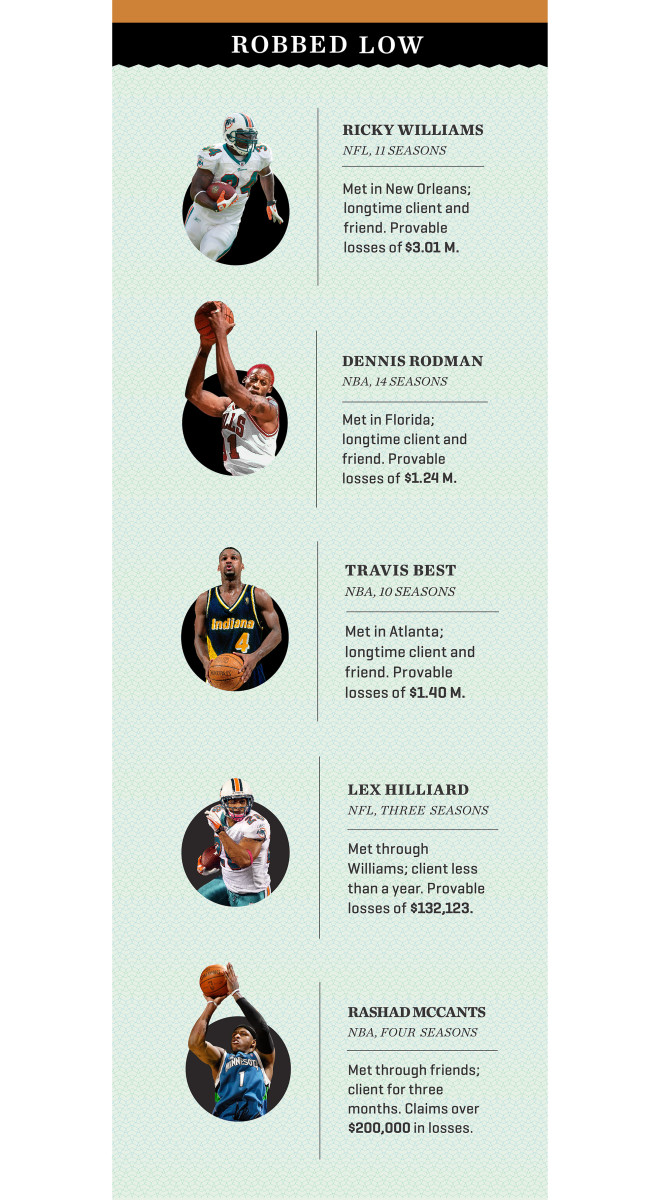

The rookie's financial hit would be softened when Garnett wired him $10,000 to cover expenses until the next payday, but McCants still remembers the wrenching realization that came when his agent confirmed the disappearance of more than $200,000, with only one plausible explanation for where it could've gone. It's the same gut punch that would be felt over the next decade by doctors, lawyers, at least four other athletes and one aerospace engineer, all of them ensnared in the same tangled criminal saga that would stretch from Texas to Florida, Saudi Arabia to North Korea.

"I was like, 'Peggy?'" McCants says. "'What? How?'"

The sizzle reel was making the rounds. This was 2011, a time when reality TV was dominated by docusoaps starring sports wives and members of the Kardashian clan, and here a refreshingly unique proposal was stirring interest among agents and network execs around L.A., as much for its supporting cast of high-profile athletes as for its charismatic, extravagant, unapologetic protagonist. Meetings were taken at VH1 and Oxygen. A pilot was ordered at BET.

A pitch document suggested a working title: The Peggy Show. Recurring characters would include Peggy's orthopedic surgeon husband as well as the man she called her "little brother," Elkin King, who was COO of her emerging sports management empire. But everything would revolve around the queen. As the first page of the pitch document outlined, beneath a picture of a middle-aged black woman with a pearly white smile, tasteful highlights in her blown-out brown hair and a face that reminded one of her ex-husbands of Halle Berry: Peggy is the owner and CEO of King Management Group. She is the business manager to 31 professional athletes who look to her to help controlling [sic] their financial lives. Money is usually the least of the partnership. Peggy has been known to furnish homes, buy engagement rings and deal with endless baby mama drama. Known as "mama" to her clients, she works with some of the biggest names in sports.

The Peggy Show was an attractive sell. "Here's an empowered woman of color in a male-dominated field who didn't take s--- from anyone," says one industry source who was affiliated with the project. "That was inspiring."

The sizzle reel, filmed at Peggy's multimillion-dollar Fort Lauderdale mansion, showcased the spoils of an accomplished life. A palm-tree-lined pool overlooking intracoastal waters. Luxury cars in the driveway. An office adorned with autographed helmets, jerseys and photos, and a Harvard diploma hanging on the wall.

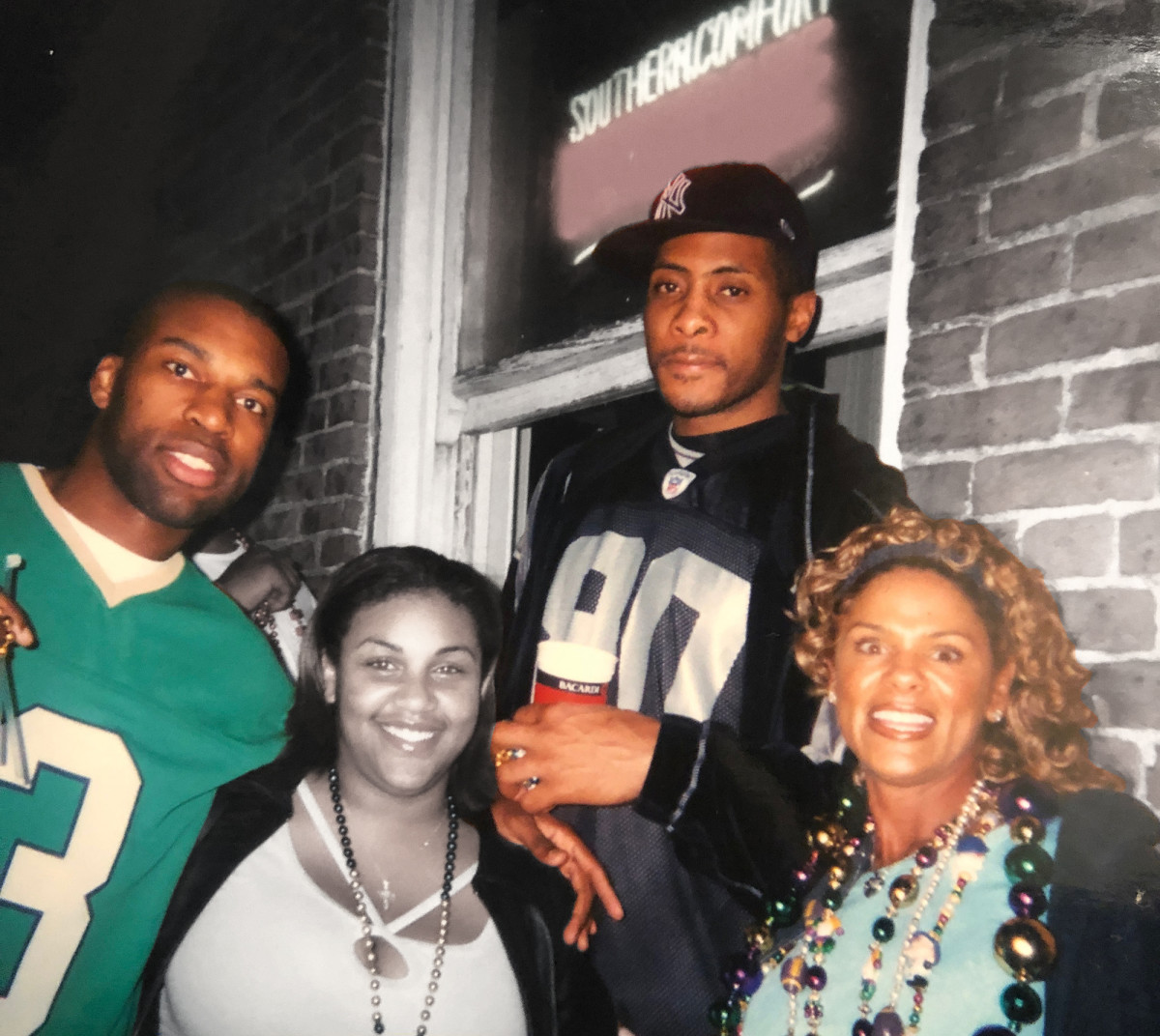

More than what she had, though, Peggy stood out for whom she knew. A list of clients in her pitch document included NBA veterans Shawn Marion and Jermaine O'Neal, NFL linebacker Marvin Jones and actor Cuba Gooding Jr. She dined in New Orleans with Hornets players, then took them apartment hunting and chatted up their teammates at the end of the home bench. She mingled alongside McCants at a VMAs after-party hosted by Jamie Foxx and lounged backstage at The Tonight Show before a client appeared with Jay Leno. She even told one friend that she dated two-time Super Bowl champion Ray Crockett.

Upon completing her Ivy League education, obtaining a Series 7 license and earning a fortune on Wall Street, Peggy explained in interviews for her sizzle reel, she'd entered sports management for selfless reasons. Not only would her investment acumen guarantee a long-term financial windfall for her clients—"Building Generational Wealth," her email signature promised—but she swore to protect them against would-be scammers. This, Peggy said, was why she insisted on working for free. Her athletes were family, and helping each other is just what family does.

Take Ricky Williams. Introduced to the NFL running back early in his career by his New Orleans interior decorator, Peggy quickly became both a professional and personal fixture. When Williams's then girlfriend, Kristin Barnes, gave birth to the couple's first child, in April 2002, it was Peggy who drove Kristin and baby Prince home from the hospital; when a second child arrived, Peggy hosted the baby shower. "She was just larger than life," Kristin says. "She could make any person feel like a million bucks."

There were Thanksgiving dinners and Christmas presents and Las Vegas vacations together. Peggy cheered from the family section when Williams played for the Dolphins and took Kristin shopping when Ricky had practice. She filed the paperwork for a health-conscious South Beach restaurant Williams launched with fellow running back Rudi Johnson, distributed invitations to a Ricky Williams Foundation fundraiser for Haiti earthquake relief and hired the photographer and caterer when Ricky and Kristin married. At Peggy's insistence, the reception was even held at her house.

That event was meant to be a low-key affair—just a few dozen relatives and friends noshing vegetarian appetizers by Peggy's pool. Then the toasts began, and a slice of drama was served.

If Williams learned anything about Peggy that evening it was that he wasn't the only athlete with whom she'd developed such a close relationship. And though Kristin was somewhat miffed at first, the bride wound up watching with amusement as Dennis Rodman—not invited, but welcomed by Peggy—snatched a microphone mid-sentence from one of Ricky's oldest friends, Kanye-on-Taylor-Swift style, and proceeded to deliver what Kristin would remember as the best speech of the night.

Less than two years after crashing the wedding of a couple he barely knew, Rodman stood behind another mike and addressed a much larger audience. Eyes cast downward, he read from a list of influential figures in his life, part of a teary-eyed Hall of Fame speech in August 2011. At one point Rodman looked up and gestured toward a woman in a silver sequin dress, seated on the aisle alongside a younger man in sunglasses, two rows in front of NBA commissioner David Stern. "Peggy King, Elkin King—these guys, the family—they're taking care of me these days," Rodman said. "Thank you, Peggy."

Here was another milestone for an A-list athlete, and again Peggy was cast in a key role. She had been hard to miss that entire week, from the moment she arrived in the lobby of the Sheraton Springfield (Mass.), filling two bellhop carts with her Louis Vuitton luggage. When the Worm worked the red carpet, she was beside him. When he walked to the stage for his speech, he stopped to hug and kiss just one person. Peggy.

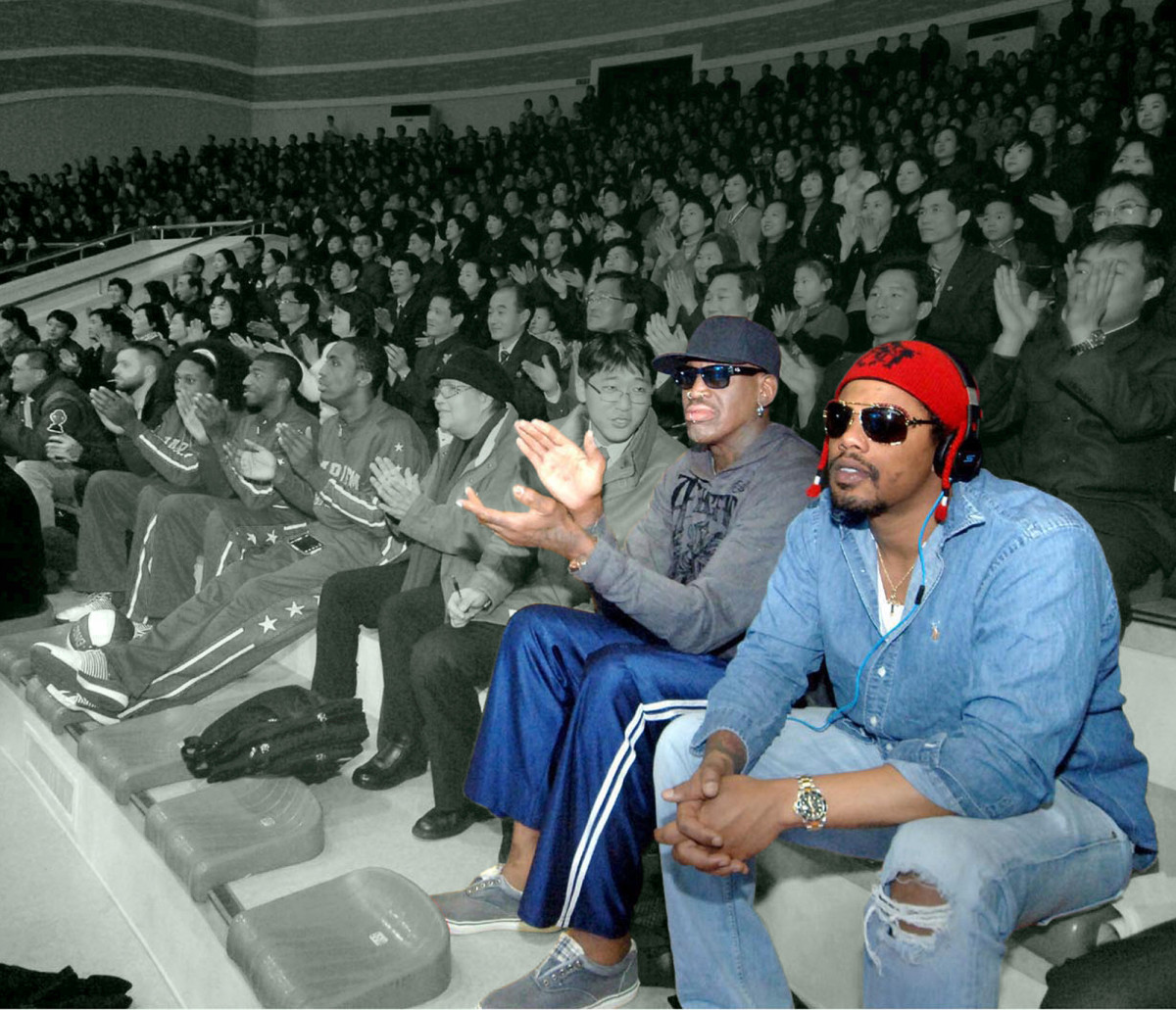

"That tells you everything you need to know," says AJ Bright, who was Rodman's personal assistant when Rodman and Peggy met through a mutual friend in the mid-2000s. But indulge here a few more examples. Like the time her then husband found Rodman microwaving leftovers in Peggy's kitchen at 7 a.m., fresh off an all-night bender, because he knew the backdoor security code. Or the time Rodman visited North Korea, in '13, becoming one of the first Americans to meet with Kim Jong-un. Not only did Elkin King sit right behind the Supreme Leader during an exhibition game in Pyongyang, but state media also later captured Elkin eating across from the dictator at a private dinner.

More than a decade after Rodman's final NBA game, people were still paying him good money for the spectacle of seeing him in the flesh. He hooped with fellow retired players in Tokyo, deejayed in St. Tropez and signed autographs at sports conventions, all for substantial cash. Overseas trips meant more than $100,000, Bright says, and domestic events generally pulled in as much as $30,000. Two other associates with knowledge of Rodman's earnings each estimate that he was bringing in more than $1 million per year during the late 2000s, largely from appearance fees and whatever compensation came from his myriad reality TV stints.

All of which made the gradual unfurling of so many financial red flags seem ominous. Lawyer Bradford Cohen remembers receiving a call from Rodman around that time, wondering why the electricity had gone off at the Florida condo Peggy had helped him find. Bright, meanwhile, recalls discovering that payments had lapsed on a $5 million life insurance policy.

Whenever these issues were raised, Peggy typically blamed Rodman's outlandish spending habits. That's how she justified taking control of his bank accounts and denying him access to a debit card: Rodman just couldn't be trusted, multiple associates remember her saying. It was all for his own good.

But suspicions reached a new height a year or so after the Hall of Fame enshrinement, when Rodman was threatened with contempt of court in Orange County, Calif., for missing four months of child support owed to his first wife. Ordered eventually to appear and explain himself, Rodman was being questioned by the opposing counsel about his spending habits when attention turned to a sizable charge at Victoria's Secret.

Later that night Rodman recounted to a friend his confusion in court: "I've never even been to Victoria's Secret."

The pawn shop was supposed to provide a nest egg for Lex Hilliard. End of the Trail Trading Post, it was called, same as the one his father had owned in Kalispell, Mont., where Lex grew up. It was a sentimental move, perhaps, for a third-year NFL fullback and special-teamer earning a league minimum salary. But Hilliard poured his heart into starting the business, not to mention his savings. Maybe, he told his wife, Rebekah, their children could inherit the place someday.

Doors opened back in Kalispell in early 2012, and buzz swelled about the hometown hero's new venture. Only, within a year every dime the Hilliards invested had disappeared. The suspected culprits, Rebekah later testified in court, were trusted members of Lex's own family.

It was under this tragic backdrop that the Hilliards enlisted the expertise of a new financial adviser, based on the recommendation of one of Lex's former Dolphins teammates—and at first Peggy was everything Ricky and Kristin Williams said she would be. Early on she lent the Hilliards $10,000 interest-free, Rebekah says. After setting up new joint checking accounts for the couple's daily expenditures—the rest of their savings would hypothetically be raking profits in mutual funds—Peggy also flew to Kalispell and acted as the Hilliards' lawyer in talks with business partners as the pawn shop rebranded and relocated.

That good faith didn't last long, though. The following spring Lex was at Jets mini-camp, optimistic about his NFL future, when his bank card was declined at the team hotel. Back in Montana with the couple's five children, Rebekah was suddenly struggling, too. A storage facility owner was demanding months of overdue bills. When the Hilliards' youngest daughter reached her third birthday, finances were too tight for a party.

After texts, calls and emails demanding an explanation went unanswered for weeks, Rebekah made what would ultimately become a critical move in the unraveling of The Peggy Show's plot. She contacted Kristin.

Casual friends from the time their husbands shared the Dolphins' backfield, Rebekah and Kristin quickly realized they were linked in a much more serious way. For the Williamses, the first sign of trouble had come one morning in April 2012, two months after Ricky retired, when Kristin went to drive their children to school and discovered the family's Range Rover had been repossessed from their condo's garage. Later that summer the IRS informed Ricky that his 2010 tax returns had been audited and that he needed to provide proof on nearly $800,000 in deductions. As Peggy always had in such moments, she promised to handle the matter. But it wasn't long before another IRS letter arrived, rejecting the deductions and dropping a bombshell: Ricky owed $375,000 in unpaid taxes, penalties and interest.

As an adopted member of the family, Peggy had always gotten the benefit of the doubt. In Kristin's words, she was "my best friend." In Peggy's words, Kristin was "the sister I never had." But now the signs were too clear to ignore. So Kristin started digging.

She asked a friend who'd attended Harvard to check the alumni database. There was no mention of Peggy. She called Charles Schwab, where Peggy claimed to have invested millions of the Williams's dollars, and found no funds in their names. She contacted the bank where Peggy had opened their checking accounts and says she was denied access. If she had further questions, she says she was told by a manager, she should consult a lawyer.

So she did. On Jan. 6, 2014, Ricky reported to U.S. District Court in Houston, where he would testify at a preliminary hearing for the civil suit he and Kristin filed against Peggy. There he explained how he met his money manager in New Orleans, how they'd been friends for years before she began handling his finances, how every NFL paycheck he earned from the Dolphins and the Ravens from '08 to '12—some $5 million posttax—plus $250,000 in endorsements was deposited into bank accounts under her control. And how the vast majority of that sum was now missing.

In the court transcript Ricky comes across as more aloof than angry. The same Ricky who trusted Kristin enough to hand over his finances six weeks after they started dating. The same Ricky described by Kristin as "generous to a fault," always willing to lend cash to any loyal friend who asked.

"For me," Ricky told the judge in court, "I'm curious, you know, where the money is."

It is a daunting task, finding the facts in a life of lies. FBI agent James Hawkins, a 30-year veteran of fraud cases, says he can't recall another scam artist who steadfastly stuck to her story, however plainly bogus it was, throughout an interview. As they spoke at her New Orleans apartment in March 2016, it didn't seem to matter that Hawkins kept producing cold, hard evidence to counter her explanations. For two straight hours, Hawkins says, "she never played it straight."

Even getting Peggy's name right can be tricky. The federal indictment handed down on Dec. 13, 2016, would list seven aliases (though five of those can be accounted for by the surnames of all her ex-husbands) and an eighth would be revealed in court. But here is what is believed to be true—based on thousands of pages of court documents, financial records, corporation filings and emails, as well as interviews with family members, business associates, law enforcement officials, sources close to her victims, and others who crossed her path—about the conwoman dubbed by one basketball agent as "the black widow of banking," "the charlatan of all charlatans" and "a f------ chameleon ghost witch."

Peggy Ann Barard was born on Oct. 10, 1958, in New Orleans, the eldest child of Donald and Juanita. She attended a Catholic elementary school in the Lower Ninth Ward, according to her father, before graduating from a local high school and enrolling at Atlanta's Spelman College, the oldest historically black women's college in the country. Contrary to the wedding announcement for Peggy's second marriage that appeared in the July 19, 1981, edition of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, it appears she did not receive an engineering degree from Georgia Tech. Nor did she attend Harvard law or business school, as she claimed on numerous occasions. The diploma in her home office would turn out to be fake, just like most of her client list. O'Neal and Jones deny they did business with Peggy; representatives for Marion and Gooding Jr. likewise say their clients never had business relationships with her.

There is no question that Peggy endured hurt before she began imposing it on others. Her younger sister died of leukemia as a baby, according to her father. Her then 28-year-old brother was shot to death in 1995 outside of the New Orleans corner store he ran. Her mother died from smoke inhalation after candles accidentally lit the family home on fire. And her first ex-husband was among the 31 people killed when a DC-9 crashed shortly after takeoff in Milwaukee, in '85.

The couple had met while Peggy was studying at Spelman, soon after which she got pregnant and dropped out, ending her formal education, according to her father. That child would be named after his dad, though for reasons no one can adequately explain, Peggy would later present Elkin Jr. (the first of her four children by three fathers) as her younger brother, both in her BET sizzle reel and to close friends. (Elkin Jr. could not be reached for comment.)

That was one of many factual oddities that Hawkins uncovered in his investigation, which was spurred by a December 2013 newspaper headline he spotted in the sports section during his lunch break at the FBI's field office in Houston: FORMER UT STAR WILLIAMS SUING FINANCIAL MANAGER. After enlisting the help of assistant U.S. attorney Belinda Beek, another criminal fraud specialist, Hawkins found himself plunged into a pinball game of misappropriated money, with funds bouncing around at a dizzying pace.

Starting with a handful of financial records provided by Ricky and Kristin Williams (whose civil suit was withdrawn once the FBI got involved), Hawkins and Beek eventually came to find that Peggy was overseeing more than 85 bank accounts. "That was the most blatant attempt I've ever seen of someone trying to hide where the money was coming from; I'd see money jump from one account, back to another, back to another," Hawkins says, rapping his hand on a table for effect. "Just bing, bing, bing, bing, bing. . . ."

Peggy's scheme was as basic as it was brazen. Typically, she would offer to manage a victim's finances—no fee—and start two bank accounts where the new client's income would be deposited as it flowed in. One was a joint account for living expenses; the other, ostensibly for investments, would be funneled into her own coffers, aided by a power of attorney that she secured thanks to her supposed legal credentials.

Other times Peggy's thievery was as simple as charging the Williamses $60,000 for their wedding when it actually cost half that, Kristin says. On another occasion, according to one of Ricky's business partners, a credit card machine at Williams's South Beach restaurant was swapped out for one that fed into an outside account.

The fruits of all these labors were readily on display. The two Bentleys and the Maserati in her Fort Lauderdale driveway were purchased with stolen funds, not to mention four Benzes, three Range Rovers, a Porsche and a Rolls-Royce Ghost. There was jewelry and clothing. Rent on a condo at Trump Towers in Miami, along with hefty mortgage installments for homes in multiple states, private school tuition, international flights and nearly $2 million in American Express bills—all of it creating the smokescreen of someone who'd worked hard and earned big.

Which was all true, in a sense. Peggy clearly applied some impressive financial literacy when it came to the art of avoiding detection. On top of those 85-plus bank accounts, Hawkins and Beek also turned up more than 20 shell corporations, registered across multiple states, through which Peggy laundered money, including the Dennis Rodman Group LLC, Dennis Rodman Group & Associates LLC and Dennis Rodman Inc.

At one point Hawkins and Beek found Peggy's financial web to be so knotted that they abandoned the dizzying quest of tracing her dirty money and instead began looking for sources of legitimate income—something—anything—that wasn't pilfered from one of her victims. "Does she have a job? Is there money coming from anywhere else?" Beek asked. "The answer was, pretty much, no."

From there, the investigation was rounded out by two major events. The first was the discovery that in 2013 Peggy had wired nearly $300,000—much of it originating from Wells Fargo funds in the Hilliards' account in Montana—to a Texas-based title company for the closure on a half-acre lot in a posh neighborhood near downtown Houston, tidily establishing federal jurisdiction in Hawkins's and Beek's backyard.

The second was the 2016 FBI interview in New Orleans. By the time Hawkins knocked on Peggy's apartment door, accompanied by two agents from the local bureau, it was clear that Peggy had hit a rough patch. Gone were the luxury cars, the multiple homes, the steady cash flow. She'd recently filed for bankruptcy (using a stolen social security number) to prevent a foreclosure on one of her Florida properties, and her fifth husband—the surgeon from the sizzle reel, which never did get turned into a TV show, had filed for an annulment on the grounds of bigamy. When that was finalized, a judge ruled that Peggy owed her ex upward of $2 million in back pay for work he'd done at King Management.

Peggy's client relationships were crumbling too. In 2015, TMZ reported that Rodman (through Cohen) had sent her a scathing missive, firing her and accusing her of fraud. Peggy denied any wrongdoing, telling TMZ, "The whole letter is crazy and bogus. I've been with him through thick and thin."

In New Orleans, Hawkins heard similar denials, again and again, regardless of what evidence he put in front of Peggy. But he was unconvinced. "I felt very confident after interviewing her that we had a good case," he says. Sure enough, FBI agents from the New Orleans office returned to her apartment in December 2016, this time with handcuffs and an eight-count federal indictment against Peggy Ann Fulford (her fifth husband's surname).

The feds would leave that day with additional ammo. While combing through her apartment, Hawkins's colleagues spotted something unusual sitting on a nightstand in plain sight: a personal check, written to Peggy by a local orthopedic surgeon for $197,000.

Hawkins looked into it. Peggy had solicited the doctor under the guise of helping finance the redevelopment of an old New Orleans high school into an assisted living facility. But the owner of the property supposedly for sale told Hawkins that she hadn't heard of Peggy. And they certainly had never done business together.

The defendant was led into Courtroom 3A through a side door, a chain restraint dangling around her waist. She wore an olive prison uniform with a long-sleeve undershirt, and her brown hair was tied in a ponytail. Standing next to her public defender, she spotted her father in the gallery and mustered a faint grin. She did not look across the aisle, where a group of her victims glared back.

Finally, Peggy was playing it somewhat straight. Confronted with overwhelming evidence, she had pleaded guilty nine months earlier, in February 2018, to count No. 4 of the federal indictment, interstate transportation of stolen property (the roughly $200,000 that she admitted looting from the Hilliards for the closing costs of that half-acre Houston lot). The other seven counts were dropped as part of a plea deal. Now she was appearing in front of Judge Keith P. Ellison of the Southern District of Texas to learn her punishment. The statutory maximum was 10 years.

After some early legal minutiae and a sniffly opening monologue from Peggy—"I accept full responsibility and any consequences associated with my actions. . . . I am so sorry that I hurt the people that I really loved"—Beek called her first witness. From the second row along the right side of the gallery, Kristin Williams walked to the stand.

"Summarizing years of lying and cheating and stealing have proved to be quite difficult for me," Kristin began, reading from a prepared statement and rattling off moments of financial misery that Peggy had caused. Like the morning when she couldn't afford groceries because her checking account was bare. The time Peggy filed for $334,000 in fraudulent tax refunds on Ricky's behalf, claimed the money for herself by posing as Ricky's wife—an easy deception, given that her fourth husband also had the last name Williams—and promptly spent it.

Back in her gallery seat, Kristin got a pat on the back from someone who knew exactly how she felt. Of the four professional athletes listed as victims in Peggy's indictment, only Travis Best had traveled to Houston for the sentencing. (Kristin spoke on Ricky's behalf, having remained close to him despite their 2016 divorce. Rebekah Hilliard represented Lex with similar testimony. No one from Rodman's camp attended.) But the presence of the former NBA point guard was fitting. After all, Beek told the court, Best was the defendant's very first prey.

Travis and Peggy met when Best was playing at Georgia Tech, in the early 1990s. James Forrest, a former college teammate and roommate, recalls seeing his friend years later, when Best and the Pacers visited the Knicks in the 2000 Eastern Conference finals, and feeling struck by how embedded Peggy had become in Travis's life. "She arranged the taxi ride, the tickets, the hotel," Forrest says. "She was like his concierge."

According to the indictment, Peggy began stealing from Best the following year, when he signed with King Management. For a time that company existed as a partnership between Peggy and her third husband, Forrest King, an emergency physician who helped negotiate deals with the Heat and the Mavericks as Best's agent. After that marriage ended, Best stuck with Peggy.

As Best's career shifted overseas in the mid-2000s, court documents say, Peggy assumed exclusive control of his bank accounts and his personal expenses. Then Best returned from his final season abroad in December 2010 and received a letter from the IRS explaining that his taxes hadn't been paid for several years. Which was odd, Best figured, given that Peggy had previously instructed him to wire $1 million into an account for that exact purpose.

Best is described by friends and associates as a frugal spender who set disciplined monthly budgets for himself throughout a 10-year NBA career during which he earned upward of $18 million. (That stands in stark contrast to Williams and Rodman, neither of whom showed much interest in the particulars of their finances.) Best eventually filed a civil lawsuit in Miami, in 2014, alleging that Peggy had embezzled more than $2 million from his accounts. Most of that came from a savvy business deal that should have formed the backbone of his post-basketball savings. In 2007, Def Jam Music Group paid Best handsomely to sign an eclectic, all-female pop group from a small label that he was funding. (Clearly Best had an eye for talent. A Girl Called Jane hit No. 5 on the Billboard Dance Club chart with "He's Alive" in June '07.)

That Best declined to address the courtroom last November for Peggy's sentencing mattered little. He'd already cooperated by sharing bank records and offering an extensive statement for a pre-sentence investigation report. Rodman had done the same. But it was the testimony of a nonathlete that sealed Peggy's fate.

An aerospace engineer who'd recently returned home to Slidell, La., exhausted from building F-15 fighter jets in Saudi Arabia and looking to bank some money for his grandchildren's college fund, Ray Thompson testified that Peggy had conned him out of multiple cash payments totaling $25,000. The money was supposedly intended for investment in a medical business. (Incredibly enough, she did this while she was out on bond following her December 2016 arrest.) When Thompson took the stand, only days had passed since he'd punched Peggy's name into Google, read an article that included her mug shot and then contacted authorities. "When I saw the picture, it just kind of blew me away," Thompson testified.

After each side's lawyer made a final statement, the judge allowed Peggy to speak one more time, and here she used the platform to claim that her fleet of luxury vehicles actually belonged to her various husbands—an easily disprovable statement that Beek shot down. A probation officer addressed the court next, estimating a "conservative [collective] loss amount of $5.7 [$5.79] million and the financial devastation of four victims and their families while the defendant lived lavishly with their hard-earned money" and recommending the maximum sentence.

Judge Ellison agreed, awarding restitution—$3,013,184 to Williams, $1,395,984 to Best, $1,243,579 to Rodman, $132,123 to Hilliard—and issuing a decade of jail time. (In reality, it's unlikely any of this money will be recovered. "Perhaps there's cash out there somewhere," Hawkins says of any remaining fortune, "but at this point I doubt it.")

The night of the sentencing, Rebekah, Kristin, Best and Thompson gathered for dinner at a sushi restaurant near the courthouse. Shots of sake were downed, as much in celebration as in relief. But a sobering reality hung over the group. As Kristin would say later, "Stealing is in her blood. She'll be running the commissary wherever she is in a couple months, I guarantee you."

Peggy is hardly alone. According to a recent study by Ernst & Young, pro athletes claimed nearly $600 million in total fraud-related losses between 2004 and '18. But that figure is based on only 35 cases available in public court documents, the alleged victims of which include Tim Duncan, Mark Sanchez, Roy Oswalt and McCants's guardian angel, Garnett. It likely represents a small fraction of the actual damage. "Extrapolating from what I know," says Steve Spiegelhalter, a former federal prosecutor who cowrote the E&Y report, "it certainly exceeds $1 billion. It's just not discovered."

In many ways Peggy wasn't much different from the classic scammer. She spoke charismatically, spent extravagantly and robbed unapologetically. So what set her apart? "The amount of time it went on," says Beek. "And the degree of personal involvement with the victims, the way she would ingratiate herself."

For those victims, the wreckage is still being sorted. Kristin estimates that she and Ricky have recouped from the IRS upward of $1.5 million in taxes paid on earnings that never actually reached their accounts. But the sense of betrayal remains. Asked to describe the process of convincing Ricky (who did not respond to messages seeking comment) that Peggy was stealing from them, Kristin replies, "It was one of the hardest things I've ever done. She was definitely a mother figure for Ricky. But I think Peggy knew which roles she could take for which people."

Best declined multiple requests for comment, but his agent, Gary Ebert, says his client too, is considering litigation and that he "feels used. He feels embarrassed. I've never heard him this hurt before. He just wants closure. He doesn't want to deal with it anymore."

Rodman, who filed a separate lawsuit seeking judgment against Peggy in Broward County, Fla., earlier this year, relayed a comment through a longtime companion: "I've got nothing to say about that. It's over. I'll never see my money."

Lex Hilliard didn't want to speak either. His career was ended by a shoulder injury in 2013. He was coaching high school football and working as a construction loader when his family's home accidentally burned down three years later. Rebekah explained his silence: "He can't go backward, because he gets really upset. He gets real pissed. It brings up a lot of s---."

Perhaps there were additional victims who stayed quiet. Like McCants, who never reported his losses to law enforcement. Certainly Peggy tried to swindle others. "I remember her," says Crockett, the retired cornerback whom Peggy told friends (falsely, he says) she dated. "She was full of s---."

Those two met in the early 2000s through mutual friends, according to Crockett, and pretty soon Peggy was whisking him off to Panama on a private jet, nudging him to invest millions in offshore casinos. Crockett stuck around for a while, he says, amused by her personality, until she bragged about having a deal with a bank where Crockett happened to know a high-level executive. One quick call to his friend put a kibosh on the slots.

These days, federal inmate No. 37001-034 resides at FCI Aliceville (Ala.), a low-security, all-women's facility four hours north of New Orleans. (In June she pleaded guilty to stealing from the doctor whose check the FBI found, and she received a three-year concurrent sentence.) Both her father and her third husband—Best's former agent, Forrest King—expressed optimism that Peggy might explain her side of this story, a story that she summarized in court like this: "I feel like I have done things that are wrong. I didn't do it maliciously. I didn't do it intentionally. It was something that just spiraled out of control, and one lie led into another one and deception." Ultimately, though, she declined an interview request.

According to her father, Peggy is getting by behind bars, taking classes and befriending fellow inmates. He says she has expressed a desire to become a teacher when she leaves prison, or maybe open a flower shop, and that she's looking forward to a fresh start at age 70. He says they speak regularly, though she doesn't have much money to call. He's been dipping into his 401(K) savings and his social security, sending her a couple hundred bucks every few weeks for the commissary.

Find more Sports Illustrated True Crime stories here