Lakers vs. Clippers: The Story Behind the NBA's Most Fascinating Non-Rivalry

The Lakers will meet the Clippers on opening night, and chances are the words “Battle for L.A.” will be bandied about liberally. When that happens, Clippers front office types will blanch—they know there’s no battle, let alone a Battle. They’re still light years behind the Lakers when it comes to the city’s hoops affections. (How else do you explain new Clips Kawhi Leonard and Paul George getting booed in their new town at a Rams game and an MMA event, respectively?)

But the fact that anyone is remotely suggesting that the teams are on something approaching equal footing—even if only in the service of hot takery—would have seemed impossible 35 years ago, when the Clippers first invaded the Lakers’ territory.

Their first meeting as co-Angelenos came on Nov. 24, 1984. At 9–5, the Lakers were in the process of rebounding from a 3–5 start, their worst in years. That early season funk had been very much out-of-character; the Lakers were in the midst of a run that would see them reach the Finals nine times in a 12-year stretch. The Clippers, on the other hand, were 4–9, which was very much on-brand.

The irony is that the Lakers had inadvertently pushed the Clippers down a path of despair—and the Clippers played a substantial role in the building of the crosstown Showtime-era dynasty. For nearly four decades, the franchises and their fortunes have been inextricably linked through a series of dealings Shakespearean in their complexity, drama and, perhaps above all, farce.

The whole thing started years before that fall night at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, in 1978, against the Lakers’ actual rival, the Boston Celtics.

A Beverly Hills–based movie producer named Irv Levin owned the storied Boston franchise, which had fallen on hard times. (Trading for Robert Parrish and drafting Larry Bird shortly thereafter would fix that.) What Levin really wanted to do was own a team in California, but he knew the league would never let him relocate the Celtics. So he engineered a deal to swap franchises with one of the league’s most moribund outfits: the Buffalo Braves, who were in the process of losing a turf war over their home arena with the Canisius men’s basketball team. Levin and Braves owner John Y. Brown—a future governor of Kentucky who had made his fortune building up KFC after he bought it from Col. Sanders—consummated the deal in July of 1978, and San Diego was home to an NBA team, which was renamed for the ships that sailed through San Diego Bay.

The Clippers weren’t the first team to try their hand in San Diego. The Rockets had been admitted to the NBA as an expansion franchise in 1967. Despite putting together a roster that included Elvin Hayes, Rudy Tomjanovich and Calvin Murphy, the team failed to win games or draw fans. In June of 1971—on the same day San Diego State named him Alumnus of the Year—local owner Robert Breitbard sold the team to a group that relocated it to Houston.

Presumably unaware of any of this, the ABA granted an expansion franchise to the city the following year. An orthodontist named Leonard Bloom got the team, which was all well and good with just about everybody except Peter Graham, who ran the 14,500-seat San Diego Sports Arena and wanted the team for himself. As a result, when the Conquistadors began play—with future Hall of Famer K.C. Jones on the bench—with three home games in three nights, they did so at San Diego State’s Peterson Gym, a facility so rundown that not even SDSU played there. Capacity was 4,200. The Q’s drew 5,230 fans to the three games, though it should be noted that since the place had no turnstiles (or concession stands), there’s a good chance that number was significantly inflated.

The next year the Conquistadors spent $600,000 to hire Wilt Chamberlain as player-coach, but the Lakers sued to prevent the 37-year-old Big Dipper from taking the court. He remained as coach, though Wilt—who was 45 minutes late for his introductory press conference—was known for skipping games for reasons such as book signings to promote his autobiography. After two-and-a-half more seasons (and a name change, to the Sails), the franchise folded.

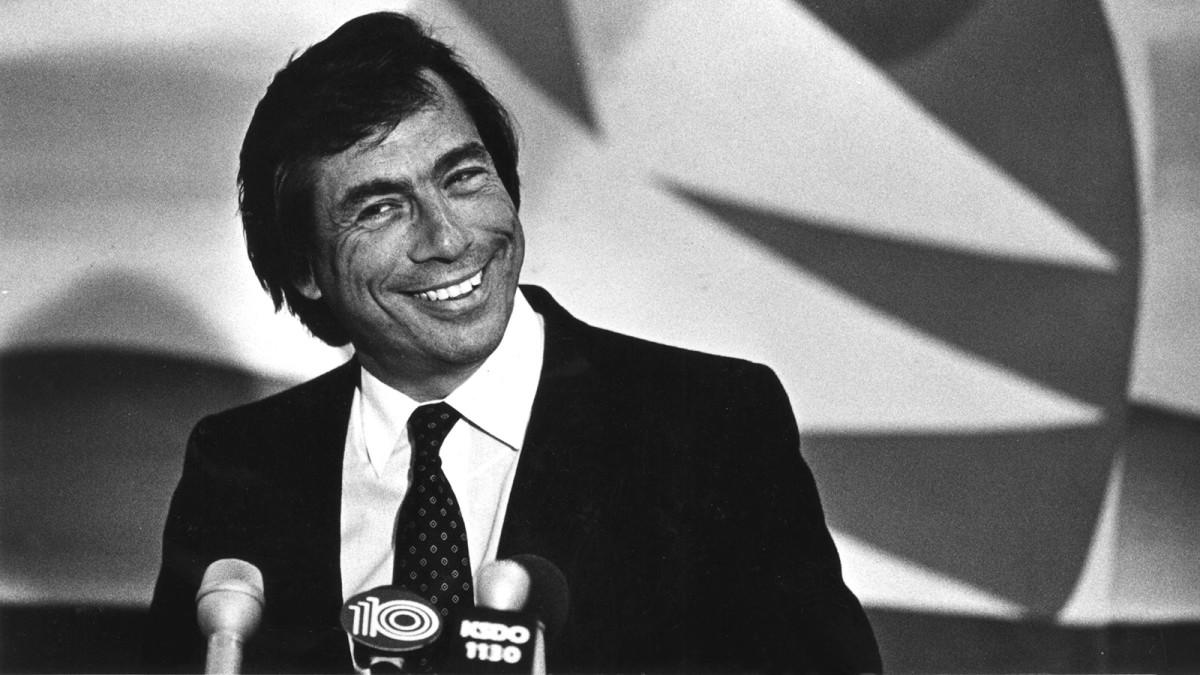

The third time was not a charm. Despite Levin’s assertion that the previous failures were due to the fact that they were played in “another era,” the apathy of fans in the 1978–79 season was still noticeable. The Sports Arena was usually around half-full at best, and on some nights less than 2,000 fans were in attendance—despite the fact that the team went on a 15–1 run late in the season. But the Clippers suffered a crushing blow on March 23, 1979—a 156–119 loss that sent the team into a tailspin that would result in them losing six of their last eight games and narrowly missing the playoffs. The team that pummeled them: the Lakers. After the game, the Lakers’ coach, who might be familiar to Clippers fans these days, added insult to injury. “Honestly, I did not feel like we that played well tonight,” groused Jerry West.

***

Around this time, Donald Sterling was one of the most successful real estate tycoons in the country. Born Donald Tokowitz, he grew up in a poor Jewish section of East L.A. After an accomplished stint as a high school gymnast, he graduated law school in 1961 and began moonlighting in a furniture store. Shortly thereafter, he changed his name to Sterling. “You have to name yourself after something that’s really good, that people have confidence in. People want to know that you’re the best,” he told a fellow salesman, according to a 1999 Los Angeles magazine story.

Sterling eventually got into the real estate game, and soon he was buying up buildings from Hollywood stars, including John Wayne and Chuck Connors—who, before he became the star of TV’s The Rifleman had played for the Celtics. Sterling continued snapping up property, including the Beverly Comstock Hotel, and was reported to be the largest property owner in Beverly Hills.

In 1979 he sold 11 Santa Monica apartment complexes to another real estate magnate, Jerry Buss, who was his Beverly Hills neighbor. Buss used the proceeds from the deal to buy the Lakers from Jack Kent Cooke that summer. Buss would spend lavishly to turn the team into a model franchise, coupling success on the court with cachet off it.

Buss also encouraged Sterling to get in on the pro hoops action. By late 1980 Levin, who was losing a million or two bucks a year, was looking to sell. Interested parties included 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo, Cavs owner Ted Stepien (one of the few worse candidates than Sterling) and, most intriguingly, a man described by the local press as “an Oregon shoe manufacturer”: Phil Knight, who reportedly had a deal all but done before balking at the $16 million asking price. Ultimately, Sterling would get the team for $13.5 million in May of 1981 and proceed to do none of the things with the Clippers that Buss did with the Lakers.

At first, though, Sterling talked the talk, or at least tried to until his preternatural need to say something idiotic presented itself. In an interview in the Los Angeles Times, on June 6, 1981, he noted that his primary responsibility was “to kids,” and as such he had stopped smoking the day he purchased the team.

Perhaps tellingly, the longest answer in the Q-and-A came when Sterling was asked to describe the contents of his office: parquet floors from Bordeaux, 300-year-old Chinese vases that required 2,000 man hours to craft, a Louis XIV desk and an armoire from the palace at Versailles. (Missing from the list: fine goblets. During the interview, Sterling got up mid-answer and went to a fridge to fill Styrofoam cup with white wine.)

Still, Sterling displayed a passion for the team. At the first game in San Diego, he celebrated baskets with what one local writer called “outrageous histrionics and a mild strip tease.” He flung aside his jacket and tie and unbuttoned so much of his shirt that it looked like he was trying to literally show the fans his heart. He raced across the court and jumped into the arms of coach Paul Silas and told each player he loved him. There were still 11 seconds on the clock.

Sterling also raved about the possibility of San Diego, saying that it was more in line with his beliefs than L.A., where the people were “too liberal,” and adding, “Making a profit isn’t everything—I care what people think of me.”

It didn’t take long for both parts of that assertion to unwind. Shortly after he bought the team, he invited some local luminaries to a luncheon that featured a $1,000 free throw shooting contest. As recounted in SI, a former San Diego State player, Miachael Spilger, hit nine of 10. Spilger was then told the prize was actually a trip to Puerto Rico—one that did not include airfare, transportation or food. After Sterling offered up the last-gasp ploy of a desperate man who knows he’s lost—double or nothing!—he then tried to get Spilger to accept Clippers tickets or a trip to Las Vegas. Only when Spilger threatened to sue did Sterling pay up, in the fall of 1982.

The owner’s cheapness extended to the team. Sterling reportedly asked Silas if he could tape players’ ankles, thereby eliminating the need for a trainer, and he wanted to slash the team’s scouting budget by 95%.

Matters weren’t helped when Sterling announced during that first season that the team was flat-out tanking for a shot at Virginia’s Ralph Sampson. “Our plan is to get the No. 1 draft choice,” he told a luncheon in January. “We must end last to draw first to get a franchise-maker.... I guarantee you that we will have the first or second or third pick in the draft.” He was fined $10,000—a quaint amount that at the time was nonetheless the largest ever assessed against an owner. (He’d see to it that the current record is much more substantial.)

The Clippers, who averaged a league-worst 5,489 fans per home game, finished 17–65, last place in the West. The only team worse was Cleveland. Normally that would have meant the Clippers and the Cavs would have held a coin toss to determine the No. 1 pick. But Cleveland had traded its pick away two years earlier. To the Lakers.

With a 50% chance of ending up in San Diego, Sampson decided to go back to school. The Lakers, despite the fact that 12 of the previous tosses had come up tails, called heads. Heads it was, and L.A. ended up with Hall of Famer James Worthy.

That spring, Sterling also launched his first attempt at moving the team to Los Angeles. In June he announced it as a fait accompli; the NBA, which heard about the plan from reporters, freaked out. After many threats of lawsuits and a few actual lawsuits, Sterling backed down a month later. At the press conference announcing that the team was staying in San Diego, GM Ted Podleski performed one of the finest moonwalks of the era, verbally backtracking in a matter of moments from, “We’ll be here forever,” to, “We’ll be here for some time,” to, “We don’t plan to be here for one year, then pull the rug out from under San Diego.”

To Podleski’s credit, they waited two. In May 1984, the Clippers announced again they were picking up stakes, this time flat-out disregarding the league’s refusal to approve the move. More lawsuits were exchanged, but this time Sterling made good on his vow.

The move came at a time when he had toned down his behavior. Following the unrest of 1982, the NBA had taken steps to potentially strip Sterling of his team, appointing a committee of owners to investigate the franchise’s finances and its less savory business practices, like not paying hotel bills and refusing to fly players in first class. Ultimately he was allowed to keep the Clippers, but lawyer Alan Rothenberg had been installed as president to oversee many of the day-to-day operations—this despite the fact that he was also employed by the Trail Blazers as a contract negotiator. (And, of course, he had played a significant role in Lakers history, having represented former owner Cooke in the talks that ultimately landed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar from the Bucks.)

For more than two years Sterling didn’t speak to the press, so he didn’t offer much in the way of explanation until well after the deed was done. But even if he didn’t fire a verbal volley over the Lakers’ bow, the move certainly wasn’t something Sterling would have undertaken had he not believed he could carve out a significant space in the Los Angeles market.

***

While Buss and Sterling had mutually enabled each other’s NBA ownership, their relationship deteriorated with Sterling’s attempt to bring his team north. Things got a little salty between the teams, especially when the Lakers found out that, while they would be playing their games at separate venues, they would be sharing a practice facility at Loyola Marymount. Lakers coach Pat Riley forbade his players from socializing at all with Clippers players when they encountered each other at the facility. He told Clippers GM Carl Scheer, “It’s like war.”

Then there was the battle for the fans. The Clippers positioned themselves as a low-cost alternative to the Lakers’ flash, calling themselves the People’s Team. They scored a W when Jack Nicholson, still bitter that the Lakers had traded Norm Nixon to San Diego, bought Clippers courtside seats to go along with his front-row perch at the Forum. (There was some speculation that he did it to guarantee the best seats for the Lakers road games at the Los Angeles Sports Arena. Whatever the reason, Nicholson’s total outlay on tickets was $100 a game for the Lakers and half that for the Clippers, meaning he spent $6,150 to sit courtside at every game in 1984–85. Single front-row seats for Tuesday night's game are going for more than double that.)

The Clippers also made a run at another Lakers gameday institution—Dancing Barry. They reportedly offered him $200 per game (the Lakers were paying him $35 at the time), which he used as leverage to get a raise from his old employers. He did show up at two early season Clippers games, though contemporaneous accounts differ on whether he was at the fateful matchup on Nov. 24, when the two L.A. teams finally faced off. Sports Illustrated reported he was at a Kings game at the Forum, citing his belief that the hoops affair was “too controversial”; the Los Angeles Times wrote that he was at the Sports Arena. (This discrepancy raises many existential questions, but they are best saved for another time.)

Strangely, Nicholson was definitely absent, but the 14,991 who did show up that night up represented the largest crowd in the Clippers’ seven-year history—though a $2 discount for fans who had weathered that afternoon’s USC-Notre Dame football game across the street at the Coliseum meant that some got in for as little as two bucks.

On the court, Worthy had 15 points in the first quarter and finished with a game-high 27 as the Lakers withstood a pesky Clippers effort for a 108–104 win. After the game, Riley spoke of the atmosphere. “This was a game that reeked of intensity,” he said. “You could feel it everywhere. That’s the way the game is meant to be played. I wish we cold have more regular season games with this much intensity.”

The next day’s Times featured the word rivalry in two headlines—on the same page, no less—and in one subhed.

But of course, nothing of the like had been born. The teams have played 153 games since that rainy November night, and the Lakers have won 101 of them. In that same time span, the Lakers have won eight NBA titles; the Clippers have never gotten out of the second round.

Lob City notwithstanding, the Clippers were always doomed to remain Hollywood’s perpetual co-star, at least as long as Sterling was producing things. He turned down chances to move in the mid-1990s, first snubbing Anaheim (he didn’t want to deal with the traffic) and then Nashville. “I never sell anything,” he said. “I’d prefer to stay in L.A. and lose money than move and make a fortune.”

As it turned out, losing and making money weren’t mutually exclusive. The Nashville offer was worth $200 million—around 15 times what Sterling paid for the team. When he finally was forced to sell following the 2014 release of tapes that contained him making racist remarks, he got 10 times the Nashville offer, or $2 billion, from Steve Ballmer (who, incredibly, has no Lakers connections).

Sterling’s departure was predictably followed by an almost palpable uptick in the franchise’s mojo. While Sterling had vacillated between overt meddling and seeming indifference, resulting in a frustrating stasis, Ballmer empowered his front office to make whatever moves they deemed necessary, no matter how radical. (RIP, Lob City.)

Though he wasn’t there for the inaugural meeting of the L.A. teams back in 1984, Nicholson did make an interesting point about how the two teams might coexist. “When you have two clubs, one’s always going to suffer at the hands of the other,” he said. “L.A. doesn’t support anything but a winner.”

In the 35 years since the Clippers left San Diego, there have only been four seasons in which both the Lakers and the Clippers have finished with winning records—and it’s only happened in consecutive seasons once. In other words, the neighbors, who have had their share of ups and downs, have never seen their ups align for any significant period of time. L.A. has never had two truly good teams before.

Until now.

Does that mean we might be witnessing the start of an r-word?

Not right away. These things take time. But given how the teams are set up—the talented rosters and the wherewithal (Ballmer recently unveiled plans for a $1 billion arena complex), resources and organizational structure to keep their fans rightfully optimistic for years to come—we’re going to find out once and for all if it can ever happen.