Kobe Bryant, Through the Years

Bryant’s first meaningful appearance in SI came in the May 6, 1996, issue, when the 17-year-old high school senior announced where he planned to “take his talent,” both coining a phrase and forever altering the landscape of the NBA. (Though not everyone thought so at the time.)

“School’s Out” (May 6, 1996)

On Monday at 2:25 p.m., the final bell rang at Lower Merion High, in the leafy suburbs of Philadelphia, and the school’s gymnasium, a museum piece circa 1964, began to fill. Boys with knapsacks on their backs scurried up the bleachers, and girls with lacrosse sticks in their hands sat cross-legged on the hardwood floor. Teachers, feigning disinterest, filled the gym's double doors. The school's athletic director, wearing his best suit and tie, tested the microphone.

On the edge of the basketball floor reporters from The Main Line Times and from the Merionite, the school newspaper, accustomed to covering events at the creaking gym without competition, found themselves making space for ESPN and The Washington Post. Members of Boyz II Men, who hail from Philadelphia and are friends of the featured speaker, hovered in the back. The name of the singing group never seemed more appropriate. On Monday at 2:35 p.m., in the same gym where he scored more schoolboy basketball points than anybody will remember, an amiable prodigy named Kobe Bryant, 17 years old, announced his plans for the future. He couldn't, after all, be a Lower Merion Ace forever. But what would come next? La Salle University, where his father, Joe (Jellybean) Bryant, is an assistant basketball coach? Villanova? Michigan? The NBA, where Joe spent eight seasons with the San Diego Clippers, the Philadelphia 76ers and the Houston Rockets?

Bryant, a 6'6" shuffler—except on a basketball court, where he moves like lightning—ambled up to the podium in a ventless sport coat and fine dress trousers bought at the last minute and in need of a tailor, his sunglasses positioned on the top of his shiny shaved head. His coat had puffy shoulders, masking his frame, which at 190 pounds is as skinny and malleable as a strand of cooked spaghetti. He leaned his goofy kid's mouth toward the microphone, mockingly brought his fingers to his unblemished chin as if he were still pondering his decision, and delivered the news that insiders had been expecting for a week.

“I’ve decided to skip college and take my talent to the NBA,” Bryant said….

In the pros he will be a guard, but whether he’s an NBA shooter remains to be determined. Also unclear is whether a 17-year-old who is truly happy with a book in his hands should be going straight into the workforce without stopping for a college education.

“I think it’s a total mistake,” says the Boston Celtics’ director of basketball development, Jon Jennings, who opposes any schoolboy's going pro. “Kevin Garnett was the best high school player I ever saw, and I wouldn’t have advised him to jump to the NBA. And Kobe is no Kevin Garnett.”

***

After a quiet rookie season, Bryant was an All-Star in his second campaign, and as the playoffs began, Ian Thomsen looked at the youngster’s evolution—and motivation.

“Show Time!” (April 27, 1998)

In [Magic] Johnson’s day TV was just becoming infatuated with the NBA, principally because of him and Larry Bird, and the new exposure made the games seem larger and made the players richer and more famous. That drove the league’s profits ever higher, so that a player today can enjoy the life of a champion without winning a title. If Bryant is unique, it might be because he didn't see the game as a way to improve his life. He was connected to the circuit by his father, a former NBA player, and the things Johnson did coursed through the little boy’s mind like the blood that pumped through the rest of him. At the same time, Kobe was isolated and sheltered from the excesses of the superstar life. His version of the American Dream differed fundamentally from that of his current NBA peers. They believed in the jackpot. Bryant grew up believing in the mythology.

“My wife and I used to prescreen movies before we’d let the kids see them," says Joe Bryant, Kobe's father. “We used to push the kids under the seat when the actors would start kissing.” Joe and his wife, Pam, were still editing Kobe's entertainment a couple of years before he signed his three-year, $3.5 million contract with the Lakers in 1996. He didn't see The Godfather, his favorite movie, until last year. “It reminds me of my family,” Kobe says. “Not because of the violence, but because of the way they all pulled for each other no matter what.”…

This debate—should Bryant be more aggressive or more of a team player?—is going to define his career. He is the Lakers’ best one-on-one player, and his ability to create his own shot, as well as dish off to his teammates, will be crucial to the team's success in the playoffs. Bryant is under the most intense scrutiny, knowing that he will receive a large part of the blame if the Lakers lose. He will have to trust his instincts if he is to become the great player who leads his teammates to a title.

“I’ve been fighting the people around me this year, as far as them questioning my shot selection and how I should adjust to them,” he says. He has adjusted somewhat. In a recent road game against the Toronto Raptors he could be seen looking first for the open man, receiving the ball in different positions and passing when he could—things often asked of less gifted players. But he also will have to be stubborn. If he continues to develop his vision, as Johnson believes he will, the Lakers will have to adapt to his strengths, on his terms.

Johnson predicts that Bryant will learn to read the game, to let it flow through him as if he were part of the circuit. “It’s going to take him two more years,” Johnson says. He has been of this opinion since the conference semifinals last May, when he watched the Lakers' postseason end in Game 5 against the Utah Jazz with four Bryant air balls—one on the final shot of regulation, three more in the disastrous overtime.

***

Johnson was right. Two years later, Bryant would win the first of his five NBA titles. In the run-up to the 2000 playoffs, SI’s Phil Taylor examined Kobe’s emergence as a star—and how that conflicted with the role the Lakers needed him to play alongside Shaquille O’Neal.

“Boy II Man” (April 24, 2000)

Thanks to His Airness, the definition of a superstar has forever changed. It’s not enough to be a perennial All-Star, an essential part of a winner, a sneaker-company pitchman. A player can’t separate himself from the pack unless he is all those things and more: a corporate mogul, a player in the entertainment world, the leader of a dynasty. Bryant is doing his best to reach the bar Jordan has raised. In December he purchased half-ownership of an Italian basketball team, Olimpia Milano, and he has endorsement deals with Adidas, Mattel and Sprite, among others, that will generate more annual income than his six-year, $71 million deal with the Lakers. Bryant is also testing the waters in show business with his CD, on which he wrote or cowrote all the songs, and in a deal with Columbia to produce albums for other artists. He has plans for Kobe Family Entertainment, his film production company, to produce movies and sitcoms. When Bryant was a gangly senior at Lower Merion (Pa.) High, many observers feared he was ruining his future by deciding to skip college. In March he was on the cover of Forbes, decked out in Armani.

An NBA title would seem to complete the picture of Bryant as an all-around success, the rare young player who has found a balance between sport and celebrity. But to measure up to Jordan, Bryant will have to be the player who leads a team to several championships. He’s not in a position to do that with the Lakers. It’s hard to be Michael Jordan when your team needs you to be Scottie Pippen.

That’s why Bryant’s willingness to tone down his game is significant. It doesn’t mean, however, that he’s content to take a backseat indefinitely. His visions don’t include an image of himself as a careerlong second banana. “Somewhere down the line when Shaq comes to me and says, ‘Kobe, I don't want to have to put up the big numbers every night, you've got to help me out,’ I'll be ready,” Bryant says. If O’Neal never makes such a request? “I’m only 21,” Bryant says. “When I’m 28, Shaq will be what, 40?” He smiles at his exaggeration, knowing O'Neal will be only 35 then. “Point is, my time will come.”

***

With Bryant on the cusp of his first crown, Richard Hoffer marveled at his game, which—good or bad—was always interesting.

“No Fear” (June 12, 2000)

[Coach Phil Jackson] has this kid Bryant out there, not so much unacquainted with defeat as he is unable to recognize it. On the other side is Scottie Pippen, a guy with six championship rings. Experience, however, is as devastating as it is reassuring, and Pippen cannot help but understand a shift in momentum late in Game 7, when his Blazers miss 13 straight shots and let Los Angeles back into the game. (“We wanted to be aggressive, but the momentum shifts,” he would say.) Pippen, mindful of the circumstances—he can recognize defeat when it shows up—abruptly disappears, scoring zero points in the telltale quarter, and doesn't even attempt a shot during his team’s 0 for 13 cold spell.

Maybe Bryant will never be so educated in the downside of life that he’ll play fearfully or even sensibly, or ever recognize shifts in momentum. It might be that he’s permanently constituted like a guy selling personal care products door-to-door, so infatuated with his own possibilities that he’ll never suffer a moment of self-doubt. Last Friday night, when the Lakers lost another of those potential closeout games to Portland, Bryant keyed a fast break by bounce-passing the ball between a defender’s legs. It was, essentially, an insult, saying the opponent was 90% air, completely permeable. Yet don’t read arrogance into the pass, only a playful willingness by Bryant to explore his own talents, to embrace the possibilities.

This kind of personality, never mind how brilliant, is going to torture you a little, too, which is why the Lakers haven’t swept anybody. Sometimes the ball goes through the defender’s legs (how the hell...?), and sometimes it goes off Bryant's foot (the idiot!). The nonchalance of youth, as when Bryant shrugs off a playoff loss with his catchphrase, “No biggie,” can be doubly maddening. The kid just doesn’t understand that with the conference finals tied 3-3 and his team down by 16, it is very much a biggie. No wonder Jackson spends so much time on the bench staring at his shoes.

Then this same kid sees Shaq angling toward the basket and, unmindful of either gaffes or glory, pitches the perfect lob, ensuring that his team avoids a wipeout. It’s quite a sight to see somebody so unshadowed by failure, so oblivious to circumstance (with its debilitating shifts in momentum), so unencumbered by defeat. So damn young.

***

After two more titles, the 2002–03 season was the first in which Bryant averaged 30 points per game—thanks in part to a ridiculous run in the spring.

“Roll of a Lifetime” (March 3, 2003)

In this age of inflated expectations, what if, for once, we did believe the hype? What if the image brokers were right seven years ago when they anointed a skinny high school senior with a shorn head as the next big thing? What if things that seemed absurdly premature at the time—the NBA’s full-page All-Star Game ad featuring the teenager opposite Michael Jordan; the grandiose pronouncements from every pundit with a word processor—turn out to have been prophetic?

That’s exactly what’s happened in the case of Kobe Bryant, which helps explain why Trail Blazers coach Maurice Cheeks could honestly say last Friday that Portland’s defense on Bryant “was pretty good overall,” even though he’d exploded for 40 points in a 92–84 Lakers victory. I’'s tough to cover a guy when, as Scottie Pippen says, “he not only takes tough shots but seems to make them all.”

Ask Yao Ming about it. At week’s end Bryant had scored 40 or more in nine straight games and 35 or more in 13 straight, a run eclipsed only by Wilt Chamberlain. Midway through this surreal scoring streak, Bryant drove baseline during a 106–99 double-overtime win over the Houston Rockets and rose up over seven and a half feet of human scaffolding for a one-handed jam so fierce that Yao would later say, “Please do not ask me about something so humiliating to my face.”

***

In the summer of 2003, Bryant was arrested and charged with sexual assault in Colorado. Though the charges were eventually dropped when his accuser declined to testify, Bryant—who issued an apology to the woman without admitting guilt—saw his image tarnished. In the spring of 2006, Jon Wertheim and Jack McCallum examined Bryant’s PR rehab—or lack thereof.

“The Great Unkown” (April 17, 2006)

“Some people are going to like me, some people aren’t going to like me,” Kobe Bryant is saying after a practice at the Lakers’ El Segundo training facility in late March. “The people who don’t, just have to understand who I truly am, and that can only happen through time. That’s why you don’t see me doing talk shows and things like that.” Opponents who marveled at Bryant's ability to compartmentalize his life while facing charges for felony sexual assault of an employee at a luxury hotel in Eagle, Colo., in 2003—he would fly to Eagle in the morning for proceedings in the case, then play an outstanding game in Los Angeles that night—say he has become an even more steely-eyed assassin since his legal difficulties. “It’s like he’s paying everybody back,” says Portland Trail Blazers guard Sebastian Telfair. “It’s like he's thinking, The best way for me to get my image back is to go out there and kill everybody. He wants to, like, murder you.”

Were you expecting a chastened, contrite post-Eagle Kobe? Bryant is adamant in his assertion that there is not—and never will be—a charm campaign to mend his image. The Lakers didn’t do anything official to try to restore Bryant as an icon to the denizens of Staples Center, no meet-and-greets with season-ticket holders, no orchestrated interviews with Oprah or Ed Bradley. “Kobe’s approach was: Let's have it be real, professional on and off the court; handle yourself the right way, every day,” says John Black, the Lakers’ director of public relations. “And, over time, people will respect that.”

NBA commissioner David Stern recalls the pleas for Bryant to be suspended even after the sexual-assault charges against him were dropped. “That is not the American way,” says Stern, who adds that “it’s clear that Kobe hasn't made this into a case of either rehabilitation or image management. It’s Kobe being Kobe.”

***

After losing to the Celtics in the 2008 Finals, Bryant won his fourth title the following year—the first he won without Shaquille O’Neal.

“Satisfaction” (June 22, 2009)

It is 2 a.m. on Thursday during the second week of the NBA Finals, and Kobe Bryant cannot sleep. In less than 24 hours the Lakers will make an unlikely comeback to win Game 4 in overtime, and three days later after a masterly 30-point performance in Game 5, Bryant will again be a champion. He will raise the Larry O’Brien trophy in his long arms, and he will laugh and hug his teammates long and deep and, yes, even tear up a little. The mask of intensity he has worn for months will finally fall.

But for now it remains. For now the Lakers lead the Magic 2–1 but are recovering from a painful loss in which Bryant missed late-game free throws. So he sits in a high-backed leather chair in the lobby of the Ritz-Carlton in Orlando, surrounded by chandeliers and white orchids and gleaming white floors, in the company of friends—a group including his security guy, team employees and trainers—but alone. He says little, the hood of his sweatshirt pulled over his scalp, his eyes staring into the inky night, past the windows and the palm trees. He holds a Corona but rarely brings it to his lips. He looks like a man so tired he cannot sleep, a man nearing the end of a long journey. It is one that began well before November, when this season started, or even last June, when the Lakers fell to the Celtics in the Finals. As he will later explain in a quiet moment, he divides his career into two bodies of work: “the Shaquille era and the post-Shaquille era.” Since the post-Shaq era began in 2004, when the Lakers traded O'Neal to Miami, many have doubted, again and again, that Bryant would ever earn a ring on his own. And while he has dismissed those who classify his legacy as Shaq-dependent, calling them “idiotic,” he also knows how close he is to banishing that perception.

Minutes pass. Bryant stares and says nothing. He has waited this long. He can wait a little longer.

Thirteen years into an exceptional NBA career, this is finally Kobe Bryant's moment. Sure, these Finals were about Phil Jackson attaining his 10th ring as a coach (surpassing Red Auerbach's record) and guard Derek Fisher's nerveless performance in Game 4 (hitting a pair of clutch three-pointers to swing the series in Los Angeles's direction) and the emergence of 23-year-old Dwight Howard (proving, as he took the Magic to the Finals, that a big man need not scowl to be dominant). But let’s be honest: This has been about Kobe all along.

***

Bryant won his final title in 2010, beating the Celtics for the first time in the Finals. After the Lakers won the West, Lee Jenkins examined the potential ramifications of that historic matchup.

“Kobe’s Final Challenge” (June 7, 2010)

“It’s never personal with me,” Bryant says with a sarcastic grin, which of course is his way of saying that it’s always personal. For a child of the 1980s who joined the Lakers before he was old enough to vote, there was perhaps nothing more personal than the loss to the Celtics in the Finals two years ago, punctuated by the 131–92 blowout in Game 6 and the bus ride in which it was rubbed in his face. “A loss like that,” intones former Celtic Bill Walton, “is an indelible stain on the soul.” Bryant will not go that far, but after he beat the Celtics at TD Garden in January on a fadeaway jumper with 7.3 seconds left, he mockingly hummed the team's unofficial anthem in the shower: “I’m Shipping Up to Boston,” by Dropkick Murphys. Bryant will now get a second chance to dropkick the Celtics in the Finals, with much more than revenge at stake.

It is hard to imagine that Bryant could be any more beloved in Los Angeles—when the ubiquitous Kiss Cam found actor Dustin Hoffman during the Western Conference finals, he planted a long smooch on his wife, Lisa, only to pull away and reveal a picture of Bryant wedged between their lips—but a victory over the Celtics would take him to Nicholsonian heights. Although several Lakers legends never beat the Celtics in the Finals, Bryant is surrounded by those who did: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar tutors the Los Angeles big men, Magic Johnson is a part owner, James Worthy hosts pre- and postgame TV shows, and Michael Cooper coaches the women's team down the road at USC. They are constant reminders that Bryant probably has at least one more hurdle to clear to become the Greatest Laker Ever. “It’s not about beating the Celtics in the regular season,” Cooper says. “You have to beat them in the playoffs. That’s when you become part of the club.”

***

Bryant retired in 2016 with five championships, two scoring titles and 18 All-Star Game nods in a 20-year career. That April, former Lakers teammate Pau Gasol described his partnership with Bryant.

“Swan Song” (April 18, 2016)

My first day with the Lakers, I met the team at The Ritz in Washington, D.C., and at 1:30 in the morning there was a knock on my door. I found out later that Kobe doesn’t sleep much. I sat on the bed, I think, and he sat on the table next to the TV. He welcomed me to the team, and then he told me it was “go” time. It was winning time. He felt I could take him to the top again, and he wanted to make sure I knew that. “This is our chance,” he said. It was powerful and meaningful.

We were a perfect fit. A lot of the triangle offense is based on reads and working off one another and understanding each other. I understood the game. I was meticulous about it. I think he appreciated that. I think he saw it as refreshing. Our relationship clicked from the beginning. We both knew we needed each other to succeed.

There are so many games in the NBA, it’s easy to start going through the motions. He kept everybody on edge. In practice he challenged people. He talked trash to people. It wasn’t for everybody. Some players can't deal with that, but I didn’t mind. It was his way of motivating you and pushing you to give more. It’s easy to get comfortable. He made sure nobody was comfortable.

***

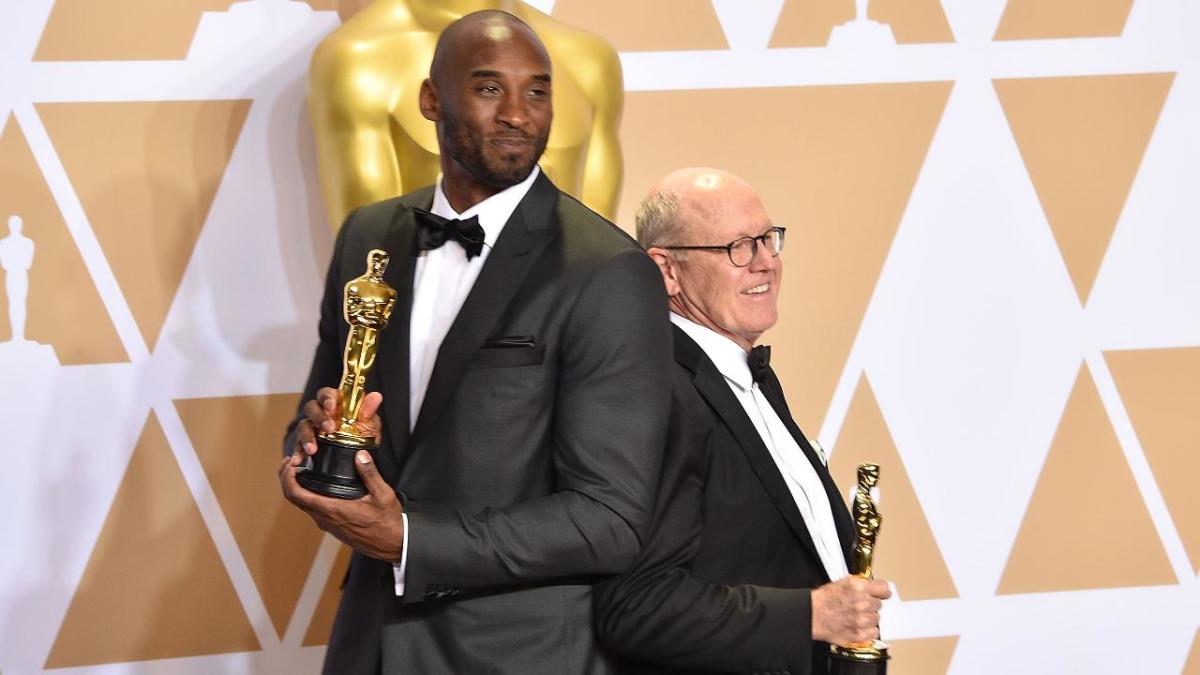

After leaving the NBA Bryant pivoted to his second act: beginning to build an entertainment empire aimed at producing content for young adults. Displaying the same focus and intensity he was known for as a player, Bryant similarly saw success, winning an Oscar in 2018 and launching a line of books.

“Fantastic Voyage” (July 16, 2018)

Bryant's larger vision will come into focus until next year, when he will release three young-adult novels written by fantasy-genre authors, all unfolding in a fictional universe where nothing is real except the sports.

“If Harry Potter and the Olympics had a baby, that would be the world we’re trying to communicate,” Bryant says. “There’s fantasy—dreamlike, magical elements—but it’s a magic kids can experience.” He discovered this world, which he calls Granity, during his last training camp at the Hilton Hawaiian Village in Honolulu. Bryant had suffered three season-ending injuries in a row and recognized his basketball career was waning. He wrestled with what to do afterward. He sounded, for a moment, like a Lost Bean. “What I love,” Bryant said one rainy afternoon at the Hilton three years ago, “is storytelling. I love the idea of creative content, whether it's mythology or animation, written or film, that can inspire people and give them something tangible they can use in their own lives.”

More Coverage of Kobe Bryant's Death:

- Kobe Bryant, Daughter Die in California Helicopter Crash

- For the Bryant Family, An Unimaginable Loss

- Kobe Bryant Left His Mark as a Generational Hero

- Sports World Reacts to Kobe Bryant's Sudden Death

- Remembering Kobe Bryant: Sports Illustrated Covers Through the Years

- Spurs-Raptors Open Game With Shot Clock Violations to Honor Kobe

- Shaq Reflects on Kobe's Passing: "There’s No Words to Express the Pain"