While the NBA Pauses, China Is Ready to Play Again. For Better or Worse

Each morning Allerik Freeman wakes up in his room at a five-star hotel, smack in the South China city of Dongguan where he and his Shenzhen Aviators teammates have been living and practicing ever since the Chinese Basketball Association indefinitely suspended games on Feb. 1 in response to the novel coronavirus. Forgoing breakfast, the 25-year-old guard, late of Baylor and N.C. State, stretches out his 6’ 3” frame and cranks out 100 push-ups and 200 sit-ups, diligent about maintaining his in-season exercise regimen, even though there are no games to play.

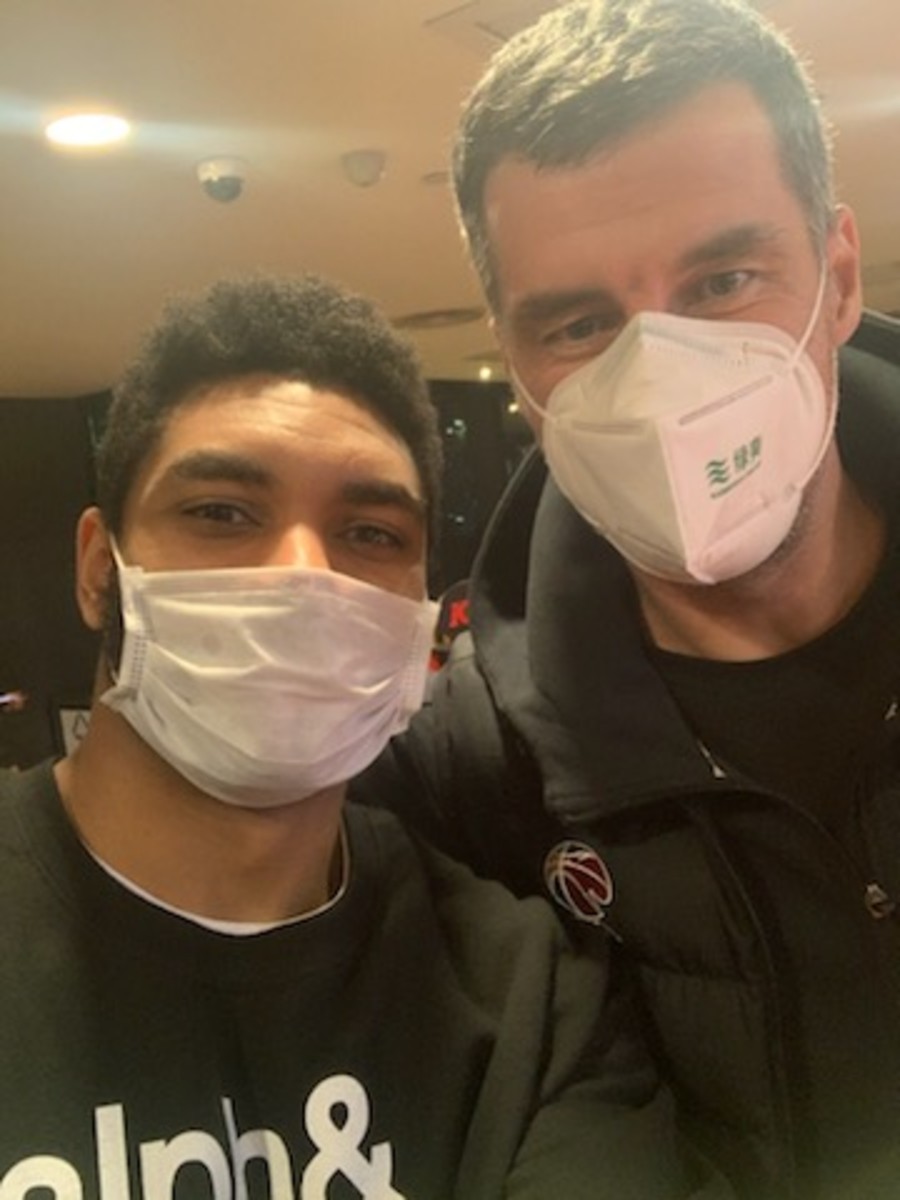

From there he grabs his gym bag and medical face mask, and he enters a world of precautionary measures. A hotel employee checks Freeman’s temperature as he exits the lobby, hovering an infrared gun over his forehead before greenlighting passage. The same thing happens at the security gate of the Aviators’ training facility in Dongguan. And again when Freeman steps on the court for practice, while team employees disinfect basketball racks and distribute hand sanitizer. And again before he can leave through the security gate. One last scan awaits upon his return to the hotel at night . . . assuming he doesn’t also order room service.

“They bring you the food,” Freeman says, “and they have the thermometer in their other hand.”

As COVID-19 proliferates around the globe, eclipsing 130,000 confirmed cases of infection and reaching official pandemic status this week, Freeman isn’t necessarily experiencing anything beyond what a billion-plus other people have throughout China, where the virus was identified by researchers more than two months ago. But his situation resonates for another reason.

Out of nearly 40 foreign “imports” in the CBA—each team is restricted to rostering two non-Chinese players at a time, a rule meant to foster domestic talent—only Freeman chose to remain in China during the outbreak. He continues to practice with the Aviators, often twice a day. He eats grilled salmon with fruit salad at the hotel restaurant every afternoon. He always wears a mask when he steps outside, which isn’t often.

“For sure going stir-crazy,” says Freeman. “Just been playing video games, watching a lot of YouTube, a lot of Netflix. I had to get one of my teammates to give me a better VPN. Even if we only have one practice, I go to the gym and get extra [work] in. A lot of stretching. You name it, I’ve been doing it to keep myself occupied.”

It’s not that 30-odd other CBA imports suddenly packed up and fled the country midseason. The league was already paused for its Lunar New Year break in late January when players learned that games would be cancelled, so most imports simply rerouted and flew home rather than return. In diverting to the U.S. from Bali, for instance, former NBA guard Ty Lawson, now under contract with the Fujian Sturgeons, says he left behind “all my stuff in China.”

By staying put, though, Freeman earned not only kudos from the Aviators, in the form of a good-soldier bonus worth nearly 25% of his total salary and a guaranteed contract of more than $100,000 per month for the rest of the season. (A 2018 All-ACC honorable mention with brief overseas stops in Hungary and Turkey, he was previously earning that amount on a month-to-month, non-guaranteed basis.) For the past seven weeks and counting, Freeman has also received a closeup look at the life of a dormant sports league, previewing the grim reality his peers in the NBA, NHL, MLB and MLS are now beginning to face.

“It’s definitely not ideal,” Freeman says. “But I think, in a few years, I’ll look back and reminisce. Like, dang, I can’t believe I was in the center of the storm when it was all happening.”

* * *

On Jan. 28, as the death toll cruised past 100 in China and fresh cases continued to emerge on multiple continents, Freeman bid farewell to his fiancée, Kiley McDermott, and five-year-old daughter, Maddox, who were flying home to Palo Alto, Calif., to wait out the virus. “I asked the team if they could book the flights for me," Freeman says, and "our translator explained how, because of the virus, the [travel] offices were closed. That’s when I knew it was pretty serious.”

From there he boarded a charter bus and rode 40 minutes north to Dongguan, as the Aviators’ usual training facility in Shenzhen had been shut down over concerns about the outbreak. Under normal circumstances, Dongguan is a bustling riverside hub of more than 8 million residents, roughly the headcount of New York City. But it felt desolate when Freeman and his teammates arrived. “Everybody was really intimidated by the virus,” he says. “The first week I was here, all the banks and grocery stores were closed. It was kind of empty.”

Still, the Aviators got right down to basketball business, practicing once each Tuesday and Thursday and holding two-a-days—shootaround and lifting in the morning, full-court drills in the afternoon—on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays at a gym run by the team owner. CBA teams have been free to hold private workouts during the hiatus, according to one league official, and here Shenzhen is hardly alone. “We all feel caught off guard,” says Shanghai Sharks center Zhang Zhaoxu, a 10-year veteran of the CBA. “But we just do what we can do: We practice.”

Like the Aviators—and the Qingdao Eagles, who are said to have briefly relocated their training to Serbia—the Sharks are getting by. Upon returning to Shanghai after the Lunar New Year break, Zhang says, he and his teammates were moved to a hotel within walking distance of their training facility near Pudong International Airport.

There some players were promptly ordered into precautionary quarantine in their rooms, eating three room-service meals a day and working out with dumbbells, all because they’d traveled by plane or train in returning from vacation. Zhang and five other teammates were able to resume training earlier, he says, because they’d been in Shanghai longer. Even then, they were barred from walking anywhere but the hotel and the gym.

A month and a half in, conditions appear to be improving. The Sharks are still housed in a hotel, but now they have one free day each week to travel. Freeman no longer has his temperature scanned when he enters 7-Eleven to stock up on Gatorade, M&Ms and other snacks that remind him of home. A recent memo from CBA chairman Yao Ming, meanwhile, projected that games could resume as early as April 2—just as the NBA goes dark for the foreseeable future.

“As basketball fans, we feel bad. [The NBA is] the No. 1 league in the world, and now it’s suspended,” Zhang says. This “also tells people that the virus in the States is going to another stage. It’s like the stage we were [previously] at in China.”

As the CBA approaches a sort of second-half tip-off, logistical questions remain. Will games be open to fans, or will they be played behind closed doors? Will teams finish their full regular-season schedules—most teams have played 30 of their planned 46 games—or adhere to some abridged new slate before the playoffs? One possible solution, according to agents, players and coaches familiar with the situation, would have CBA clubs traveling to one or more host cities and competing in a controlled environment, round-robin style.

The biggest hurdle, however, concerns the league’s biggest stars: Will the imports even come back?

* * *

Freeman and his peers occupy a unique space in the pro sports world. Foreign players are hot commodities in the CBA, lured by a season that lasts less than five months and by high salaries that often climb past $1 million. Their contracts are laced with performance bonuses and lifestyle perks, such as translators, drivers and plane tickets for family members to tag along on road trips. Where Freeman was booked posh accommodations in Dongguan, his Chinese-born teammates moved into dorm-style apartments during their pseudo-quarantine.

But that comfort rarely lasts. Per CBA bylaws, teams can switch out their imports up to four times in the regular season, then twice more in the playoffs. As such, players are often signed and released at dizzying rates. When Freeman debuted for the Aviators on Jan. 5, dropping 22 points and nine assists in a narrow loss to the Beijing Ducks, he was their fifth foreign player of the season. Among his predecessors: 2013 NBA lottery pick Shabazz Muhammad and reigning CBA leading scorer Pierre Jackson, neither of whom lasted even a month into the season.

Against this backdrop, a potential standoff is unfolding as the CBA readies to return. The league has asked import players to rejoin their teams as soon as possible, but only a handful beyond Freeman have thus far obliged. Why? According to two agents with multiple foreign CBA clients, some teams began withholding salary money once the players departed—leverage, as the agents see it, to ensure the players’ eventual return.

“Players want to be paid,” one agent says. “Then they’ll go.”

Above all else there is the spectre of the virus. “Most teams didn’t give players authorization to leave, but they left anyway because they were scared for their lives,” the same agent says. And with COVID-19 evolving into a worldwide pandemic, with rising casualties in the U.S. and Europe, CBA sources say that players have been told to anticipate the possibility of spending a mandated week or more in precautionary isolation upon their return. Which could prove problematic. “I’m cool with going [back],” says one European-born CBA veteran who has been riding out the hiatus in his home country. “[Only] if someone can guarantee that I’ll not end up in quarantine for no reason.”

Some imports, meanwhile, have used the hiatus to find new gigs. Former Wizards guard Chasson Randle left the Tianjin Pioneers to sign a 10-day contract with the Warriors, while the Liaoning Flying Leopards’ Lance Stephenson—yes, that Lance Stephenson—was reported to be nearing a deal with the Pacers, at least until the NBA suspended operations too. Some remain home, seeking further assurances about the security of their health or their money, or both. For others, a return to China is the only viable option. “Under contract,” Lawson says. “I have to.”

Freeman’s decision wasn’t tough. After earning roughly $4,500 a month to play in Hungary last season, simply getting a foot in the CBA door was a big personal milestone given his lack of international name recognition. He appeared only four times for the Aviators after they acquired his rights from the Turkish club Bursaspor last December, but he dropped 40 points in the last game before the league shuttered. Soon afterward he received a visit from Shenzhen’s general manager. “He basically asked, ‘What’s your plan?’ ” remembers Freeman. “I was thinking, Is it worth me staying? We got the guaranteed deal. I felt like, O.K., it’s a little more worth it now.”

Freeman made a business choice—one that, as another CBA source puts it, has the potential to make him “look like the hero” to teams and fans. More than anything, though, he was motivated by how quickly the virus spread beyond China. That spread, he says, is why he declined recent offers from two Italian teams, plus a few others around Europe. “If I were to go play again in Turkey, or in Spain or Germany, who’s to say that in three weeks a high number of cases aren’t there?”

Freeman is making the most of his time in basketball limbo. He has enjoyed building chemistry for the stretch run of the season with his Chinese teammates, competing against them in FIFA and NBA 2K, learning some Mandarin and attending a group barbecue, where he sizzled meat and vegetable skewers over a charcoal grill. “I would say things are back to normal—as normal as they’ve ever been,” he says.

The only downside, really, is being apart from Kiley and Maddox, who remain 15 hours behind, in Palo Alto. They video chat before Freeman falls asleep each night, catching up on the news of the day. But he’s not sure about flying them back to China. Traveling, he says, just doesn’t make sense in this uncertain climate, with this uncertain disease.

“I’m just happy they’re safe . . . But now it sounds like America is starting to become worse than China. At first I was really happy—they’re out of harm’s way. Now it’s like: Dang, it’s about to get really bad there.”