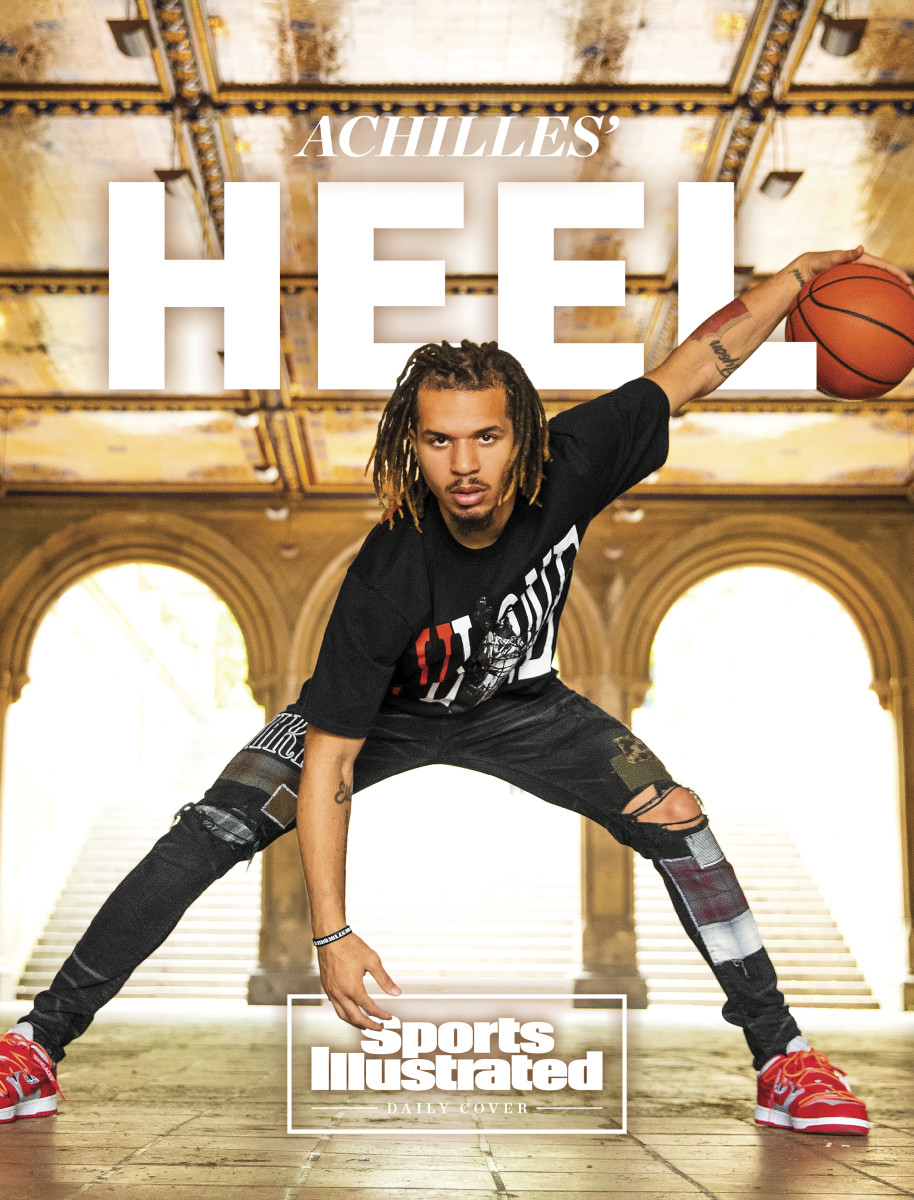

Cole Anthony Is Full of Fire

Shelter in place inside his family’s duplex apartment on Central Park West is a time of reflection for Cole Anthony, a one-and-done point guard from North Carolina, as he readies for the NBA draft, when he’s a likely lottery pick. There is much to contemplate in a city, even before it was seized by police-brutality protests following the killing of George Floyd.

When Anthony ventures outside for a walk the impact of COVID-19 on New York City is palpable: Wearing an N95 mask, he often goes past a field hospital set up for the overflow of patients. “Clear roads is the craziest thing to me,” he says. “Seeing no traffic is insane.”

The family’s living space, adorned with oils by the likes of Henry Ossawa Tanner and artifacts that date to 300 B.C.E., invites introspection. (And power: It has also hosted a fundraiser for California Senator Kamala Harris and a reception for former New York City Police Commissioner William J. Bratton.) Cole’s stepfather, Ray McGuire, a Citigroup vice chairman and a rumored Democratic candidate for New York City mayor in 2021, is an avid collector. Cole’s mother, Crystal McCrary, is a lawyer, novelist and documentary filmmaker. Both protect their collection like docents. “The first thing that Ray and Miss Crystal say when you go up to the house is that first little gallery area is completely off limits,” says Judah McIntyre, a friend of Cole’s since childhood. “There’s like four chairs there. Nobody sits down.”

Cole’s sleep cycle has been inconsistent of late. He goes days without seeing his sister, Ella, 17, who is wrapping up her senior year at the Horace Mann School. Their father is Greg Anthony, the former NBA point guard, and she too has followed in his playmaking footsteps, leading the Lions to their first state title in two decades. Basketball is forever in the air. Recent purchases to occupy their brother, Leo, include a Pop-A-Shot machine.

Cole is back after two years in the South, first for his senior season at Oak Hill Academy in Mouth of Wilson, Va., then a whistle stop in Chapel Hill. He commenced his freshman campaign with 34 points, 11 rebounds and five assists in a 76–65 win over Notre Dame, a performance that his coach, Roy Williams, called “the most sensational debut I’ve seen, and it’s not even close.”

His fall was epic, too. After leading UNC to a 6–1 start and the No. 5 ranking, Anthony missed 11 games due to a right knee injury. The Tar Heels dropped five straight games during one stretch without him and then another seven in a row after he returned. They finished 14–19 and tied for last in the ACC. Anthony’s finale included more turnovers (six) than points (five) in an 81–53 loss to Syracuse. Williams defended the go-to guard’s role in the team’s dismal season, calling the supporting cast “the least gifted” he’d overseen in his 32 seasons as a head coach.

“Such a rash of injuries and bad plays and bad luck and bad coaching,” Williams says. “We needed him to penetrate and throw the ball to himself.”

Now Anthony again finds himself with no one to pass to. The gym in his building is closed; rims have been removed from most playgrounds. “I’ve had to resort to polishing the mind,” he says.

Typically afforded access to private trainers and exclusive facilities, he now performs what he calls his “jail workout”—pushups and crunches—to stay in shape during lockdown. He reviews game film and he engages his stepfather in conversations about building wealth. In public, he practices social distancing and is acting charitably, delivering meals to health care workers at Harlem Hospital. He’s been active on social media, posting a clenched black fist and writing, “Together we stand, Together we are stronger” on Instagram. “I’ve really tried to get in touch with the political and social aspect of the world,” he said shortly before the protests began. “Why not educate yourself, especially when you have the knowledge around you? I really just try to take advantage of all these connections.”

He also went on NBA TV to do an interview with his father. “It was really cool to embarrass him a little bit,” says Cole, who needled Greg for not having a background setup at his home. (Cole had arrayed plaques and sneakers for the shots from his room.) “I hope he was a proud father because I am a proud son.”

His mother wants him to chip in on more chores. Frustrated by plates left in the sink and the accumulation of crumbs on counters, she recently took Sharpie to two pieces of paper and affixed them to the cabinets.

“PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE!!!” she wrote before outlining her requests. “Please, help to keep every part of your home clean!!”

***

Cole Hinton Anthony was born in Portland on May 15, 2000, an off day between Games 4 and 5 of the Western Conference semifinal series. Greg was a Trail Blazer then, backing up Damon Stoudamire on a 59-win team. Portland closed out the series the next day and then lost to the Lakers in the conference finals.

Greg cut a memorable figure in the game, a lefthander with right-leaning politics. As a 6-foot junior he led UNLV’s outlaw Runnin’ Rebels to the 1990 NCAA title while also holding a membership in the Young Republicans. Taken by the Knicks with the No. 12 pick in ’91, he earned a technical foul in his NBA debut. By the time Cole turned two, Greg, who never knew his father, had logged his last minute in the NBA, having played for six teams over 11 seasons.

He and Crystal were introduced by mutual friends when she was at law school. Crystal occupied a distinct space in the sports world, too. She grew close with Rita Ewing, the wife of Knicks star Patrick. The women, both lawyers, cowrote Homecourt Advantage, a steamy novel about wives and girlfriends in the NBA that was published in 1998. In the acknowledgments, Rita wrote, “Biggup to my husband.” Crystal dedicated her end to her parents, and “for my husband, Greg, who helped me find strength.”

She’d need it to deal with their firstborn. Crystal recalls Cole crying for a half-hour after losing a footrace when he was three years old, one of many tantrums. The parents divorced around that period, and by the time Cole was in the third grade Greg, who began splitting time between New York City and Florida in 2004, was marveling at his son’s contentious nature. If Cole and Ella each had bowls of Cheerios, Cole would count his sister’s share. “He was two years older so if it was equal, it wasn’t equal,” Greg says. “He should have more.”

That ultracompetitiveness carried over onto the floor. Despite having played for a Knicks team known for bruising style, Greg was not prepared for his third-grade son’s imitation of Charles Oakley. “I didn’t even know they gave flagrant fouls at that level,” Greg says. “I didn’t think he would carry the mantle quite so directly.”

Cole’s first youth-league coach, Carl Benn, remembers an opposing coach asking, “Do you think his mother would allow him to play football with us?” His second coach, Billy Council, describes Cole’s attitude at the time as “pit bull.” McIntyre, who was also Anthony’s teammate, adds, “If he missed two or three shots in a row, he would hit himself. It was the Cole Tantrum.”

Both parents sought to rein him in. They signed him up for golf and tennis lessons. He played soccer and baseball, too. When he transferred from Horace Mann in the Bronx to Poly Prep in Brooklyn, he repeated the fifth grade due to “emotional and maturity issues,” Greg says. “He wasn’t a happy camper about it.”

Cole’s growing pains were captured on camera, too. In 2011, Crystal directed a documentary crew on Cole’s AAU team as it reached the national tournament in Detroit. She says she believed the 81-minute film, which aired on Nickelodeon in ’15, would show the “last days of innocence.” Due to a series of outbursts, Cole was suspended for the first half of the championship. The team lost in the final, but Cole made a lasting statement later as he held a stuffed giraffe and said, “I plan on playing basketball my whole life and in the NBA as soon as possible, for as long as I can.”

That was news to his family. Greg didn’t believe Cole was all that talented, and he wasn’t asking his dad for help. But the next season Cole’s AAU coach, Stephen Harris, said he could be the best player in the country—if he controlled his emotions. “I told him there’s only room for one loose cannon, and that’s me,” Harris says.

As Cole developed his jumper, he started to measure himself against Greg. One day, son asked father how old he was when he first dunked. Greg told him ninth grade. Cole vowed to dunk in the eighth, and did.

While Cole has strived to replicate his father’s success, he’s also witnessed his mistakes. Greg was charged with soliciting a prostitute in Washington in January 2015. He was suspended by CBS and Turner Sports, but avoided prosecution and returned to the air that summer when he called summer league for NBA TV.

Greg publicly apologized for “a lapse of judgment.” He also encouraged his son to aspire to have a better career than his. “I finally told him, ‘Look, buddy, I was a decent player,’ ” Greg says, “ ‘but you want your goals to be set a hell of a lot higher than my accomplishments.’ ”

***

At 4:45 a.m., Carl Benn would wake up in Far Rockaway, Queens, drive 25 miles to the Jewish Community Center in Manhattan and put Cole, whose commute was two blocks, through workouts. It was the fall of 2015. When Cole finished, he showered before setting off for Archbishop Molloy High in the Briarwood section of Queens, the Catholic school that produced NBA point guards Kenny Anderson and Kenny Smith. Before his season, Anthony was named the starting point guard.

The team, which also featured 7-footer Moses Brown, who’s now with the Trail Blazers, reached the Catholic League final against Cardinal Hayes the following season. But Anthony, pushing the pace, was stripped of the ball on a drive with 30 seconds left. He then failed to finish a pair of layups in a two-point loss.

Still, he was making a name for himself: His pregame routine at home games included throwing the ball off a brick wall behind the basket, grabbing the ricochet, switching the ball between his legs while in the air and dunking violently. Fans asked for selfies with Anthony after road games, and the press took interest. “I see dudes like Trae Young and Steph Curry,” he told one interviewer. “I know I can shoot as good as them, if not better.”

Anthony’s audience grew online, as well. A trove of his dunks was archived on Overtime.tv, and he became an Instagram sensation the summer after his junior season. He was on vacation in the Bahamas with his mom, staying at the same house as Shaquille O’Neal. Dressed in sandals and wearing a fanny pack across his chest, Cole nodded to a friend and told him to record on his phone. As Shaq stood next to a 6-foot basket with his back turned, Cole dunked on him. Anthony posted the video on Instagram, where he already had 282,000 followers. The post has more than one million views. “Caught him slipping,” Cole says.

Later that month Anthony traveled to North Augusta, S.C., for the Peach Jam, a huge nonscholastic tournament. Former NBA star Jermaine O’Neal, who played with Greg in Portland, coached an opposing team and took the measure of the kid with a 43-inch vertical.

“He is Greg 2.0,” O’Neal says. “Crazy athlete. More athletic than his dad. He is tough-nosed and tough-minded like his dad. He’s already a better scorer. Greg was always able to shoot, but not off the dribble like that.”

On the second morning, after the end of warmups and before tip-off, Cole walked to the bench. Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski leaned against a wall; Williams watched from a baseline. Greg was right behind the bench, too, drinking coffee when he attempted to address Cole.

“I’m mentally locked in,” Cole said. “We can talk after.”

Cole came out cold, and though he stormed back in the second half, the Cardinals trailed by 12 in the last minute. Coach Terrance (Munch) Williams sent in a sub for his star.

“Leave me, Munch!” Cole shouted. “Leave me, Munch!”

Williams reaffirmed his decision. Cole’s ire grew.

“What are we f------ doing?” Cole said. “What the f--- are we doing? This is Peach Jam!”

Greg shouted, “Yo!”

Cole relented and left the court.

The Cardinals lost and would not make it to the weekend’s cut. Ella reached over to console her brother as he packed his bag.

“Do not touch me!” he yelled. “Do not touch me!”

A few weeks later he won gold with Team USA at the FIBA Americas U-18 Championship in Canada before transferring to Oak Hill, where weight-lifting is a class and the team has a national schedule. He grew his hair out, braided it into dreadlocks and frosted the tips. When he left Mouth of Wilson he was the most sought-after point guard recruit in the country.

***

On the day Cole moved to Chapel Hill last summer his brother, Leo, and Bryce Council, a longtime friend, found an outdoor court in the South Campus dormitories. The trio was playing when Greg showed up. A grudge match resumed between father and son. A football camp let out and a crowd formed on the baseline and sideline. Cole prevailed but Greg, dressed in blue pants, sneakers and a backward hat, nailed a few fadeaways.

“When I don’t want to lose, I lose sight of everything else,” Cole says. “My mind goes blank except for that one subject.”

Described by Williams as “gregarious and New York talkative,” Anthony ingratiated himself on campus right away, overseeing dunk contests at the frats on lowered rims. After hitting six three-pointers in the Tar Heels’ opener, he proved resolute on defense as well. During a Thanksgiving tournament in the Bahamas, Anthony was the last line of defense against an Oregon fastbreak. When Shakur Juiston, a 6' 7" forward, caught the ball on the left wing and rose to dunk, Anthony sprinted to the rim, leaped off two feet and rejected him. On the flight home, though, he wore a protective boot on his right leg, which he injured during the game. After laboring through two more contests he noticed swelling in his knee; an MRI revealed a slight tear of the meniscus. When told he needed surgery, he wept.

“I felt like my whole world was done,” he says.

To keep Anthony’s head in the game, Williams had him sit with the coaches on the bench. When he returned two months later, the humbling began. In his first game back, trailing Boston College by a point with four seconds left, Anthony airballed a three. At Notre Dame a week and a half later, he scored 23 points on 7-of-16 shooting, but fans taunted him, shouting, “Sec-ond! Roun-der!” during free throws. UNC lost again.

He finally looked like the star from the opener when he returned to New York City to face Syracuse on Feb. 29. Cole finished with seven threes and scored 25 points in a 92–75 win. It was a reminder of the season’s unmet potential.

The final blow came just before the pandemic ended the season, when Syracuse got revenge, blowing out the Tar Heels by 28. Anthony made just one three in the most lopsided ACC tournament loss in school history. “His shot needs to get better, his decision-making needs to get better, his strength and conditioning needs to get better,” Williams says. “But he’s got it, the I-T. No one will outwork Cole.”

NBA teams are intrigued by Anthony’s ability to score—he averaged 18.5 points as a freshman on 38.0% shooting (34.8% from three)—but many wonder whether he’s enough of a playmaker to be a true point guard. Then there’s the issue of his temperament. One NBA scout says he “needs to learn to manifest his competitiveness in a more constructive manner. He can be overly demonstrative, especially when his teammates make mistakes. His attitude tends to be the biggest hesitation teams have.”

Cole—who Williams says was “tremendously easy to coach”—notes that he wasn’t confident until a growth spurt in seventh grade and that he’s likely overcompensating now. He attributes his fire to his “will to win.” but concedes he is working to become less combative.

Back at home, he hosted a Q&A on Instagram Live with three residents at the Brooklyn Hospital Center. Though he focused on the virus after returning to New York, many of his 600,000 followers asked about his plans in the comments section:

You’re getting drafted #1

Stay at UNC!!

Will corona prevent you from going pro for a year?

Four days later, he entered the draft.

***

On a recent weekday, Cole and Leo made their way across Central Park’s Oak Bridge, in part, to compete in Pokémon Go, an augmented reality game that melds technology with the physical world. As they used their smartphones to capture the digital exotic monsters, Crystal guided them toward greenery and a stream.

“It was Zen-like,” Cole says.

Appreciation is a regular topic of conversation between mother and son. It comes up in talks about the financial advantages he has enjoyed. One night recently, Cole walked around the block when he happened upon a Lamborghini parked on the street. As he posed for photos in front of it, Crystal explained the dangers of accumulating depreciating assets. Their larger conversations often veer toward civil rights history, social justice and, as she says, “the promise of what this nation is supposed to be through the constitution and case law.”

“All of us have been doing, doing, doing instead of stopping and reflecting,” Crystal says. “I think what this moment has done for us is cause us to think differently.”

Even as Cole seeks calm, family members hear echoes. Leo and Cole are close despite the age difference. Harris, the coach who told Cole he would be the best player in the nation, sees similarities. Leo is more mature than Cole at the same age, but Leo earned his first technical foul last winter. Harris looked at Crystal.

“Oh no!” he said. “Not this again!”