'We Ain't Wired Like That.' How the Heat Rebuilt Without Tanking

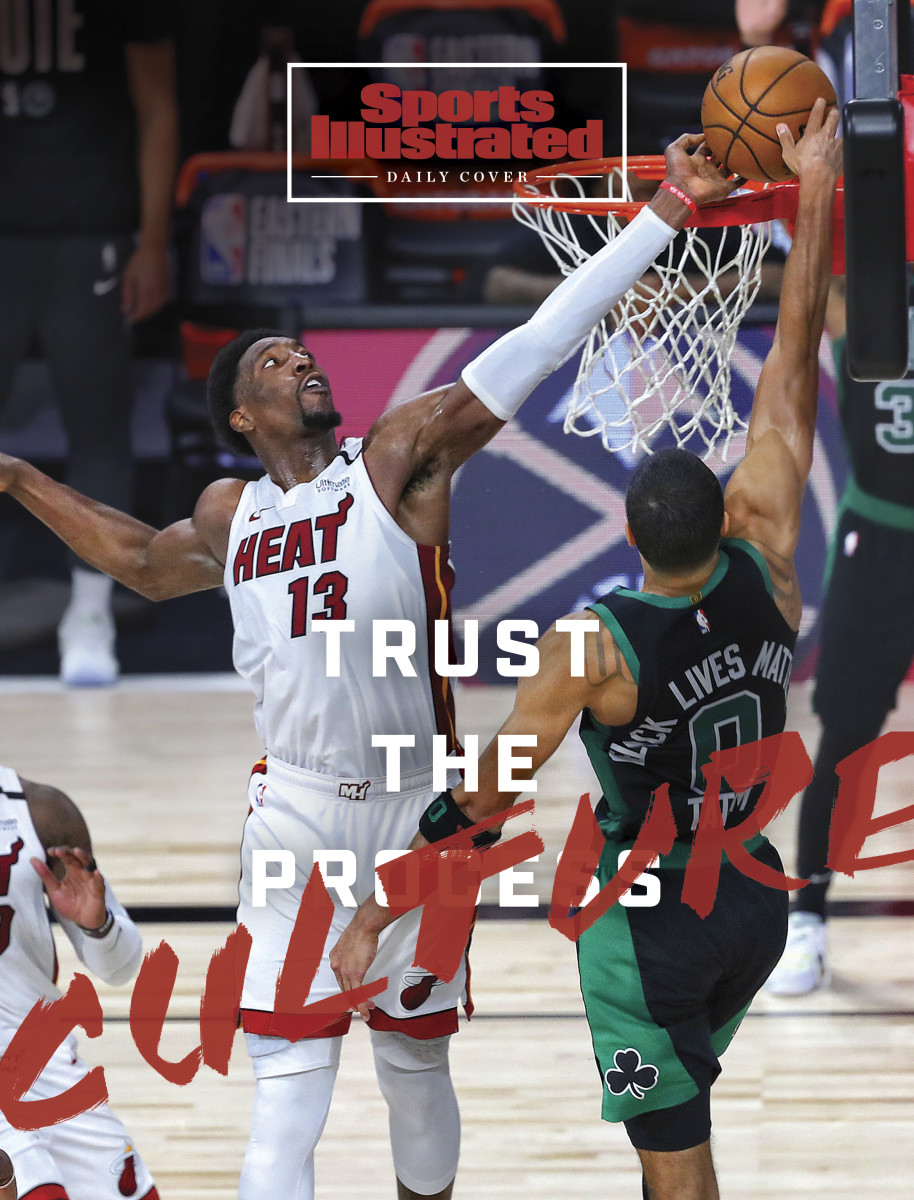

LAKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. — It looked like Bam Adebayo came out of nowhere, but he didn’t. When Adebayo blocked Jayson Tatum’s dunk at the end of Game 1 of the Eastern Conference finals, he flew in from Heat practice, from the film room, from a culture that Pat Riley created 25 years ago and has always maintained.

If life is a game of risk and reward, there were two ways to look at Adebayo’s block. As coach Erik Spoelstra said afterward, “That can be a poster dunk, and a lot of people won't be willing or aren't willing to make that play and put themselves out there.” That was not just a possibility when Adebayo ran over to Tatum; it was likely. It could have been like Damian Lillard waving goodbye to Paul George last year (even though it was only Game 1).

Everybody in the Heat organization understands his teammates might have asked why he didn’t try. Adebayo was not going to risk that. It’s not the Heat way. As Jimmy Butler said of Adebayo afterward, “I love how he does anything and everything that you ask him to do, I really do.”

After Butler hit two huge shots in Game 1, Spoelstra said, “The most important thing about that is having guys that are willing to put themselves out there. He's vulnerable enough to put himself out there, and that's why we have him.”

It is exactly why Butler ended up in Miami. It is why the Heat wanted him and why he chose to go to Miami. Butler is the NBA’s ultimate worker, the rare superstar who isn’t just tough, but became a superstar because of how tough he is. Some players get knocked down in the first quarter and won’t enter the paint again. Butler just drives harder to the bucket the next time.

The Heat is not here for your nonsense, your platitudes and, especially, your tanking. Sometimes the team is great. Sometimes, just pretty good. But the foundation is always in place. Adebayo blocked Tatum’s shot because he is a great defensive player. But he tries to make those plays all year because that’s what the Heat do.

“We rely on pushing each other and making each other better, and trust and honesty and open conversation, which are some things that don’t happen in the NBA anymore,” says veteran Udonis Haslem, a key player on three title teams who barely plays now. “A lot of people tell people what they want to hear instead of what they need to hear. We believe in telling you what you need to hear only in the way of making you better.”

When Haslem talks to friends on other teams, does he see how lucky he is?

He laughs.

“I don’t got no friends on other teams,” he says. “That’s another part of the culture.”

Six years ago, LeBron James took his talents back to Cleveland. Miami was left with an aging roster. One star, Chris Bosh, would retire early because of blood clots. Another, Dwyane Wade, left for Chicago in 2016.

If there was any question about how Miami would handle its downturn, Joel Anthony could have answered it. Anthony was a backup center on the Heat’s 2012 and 2013 championship teams. But he was also a rookie in 2007–08, when the Heat went 15–67.

That was Riley’s last year as an NBA head coach. The Heat were terrible, but they were not tanking. They were two years removed from a title. They began the season with Wade and Shaquille O’Neal on the roster. Wade got hurt, Shaq got traded, and the team fell apart. But if you watched the Heat practice that year, you wouldn’t have known it. Anthony says that team practiced as hard as the teams that would win titles a few years later.

“In terms of the work that was being put in, that never changed,” Anthony says. “It’s not as if we took things easier, regardless of how we were doing or what the record was. The Heat identity is still the same. I saw it in the locker room with guys, how difficult it was. It was driving everyone crazy. We were trying to win.”

Riley retired from coaching that year, stayed in the front office, and hired Spoelstra to succeed him. LeBron came, won and left. The Heat spent the next few years in what is supposedly the worst possible place for an NBA team. Call it mediocrity or purgatory. The Heat were too good to get a top-three draft pick but were not real contenders.

But Riley once said there are two outcomes in basketball: winning and misery. He will never choose misery. He kept trying to win. He spent in free agency, traded draft picks for Goran Dragic, and kept the Heat afloat. It looked like a stubborn refusal to take his medicine, but it is the only way Riley knows, or wants to know.

“I know Pat. I know Spo. We ain’t wired like that,” Haslem says. “We ain’t wired to throw away a season. We ain’t wired to come in and work hard every day just to lose.”

This is the mentality you expect in the NFL. But the NBA is different. It’s a star-driven league. The conventional wisdom is that you need to do everything you can to get one, which often means being really awful and getting a high draft pick.

Look around the NBA, and you’ll see plenty of teams that were awful—either intentionally or unintentionally—and drafted high-end talent. Last year, Butler played for two of them, in Minnesota and Philadelphia. He openly bristled at having young, gifted teammates who were not as committed as he was. Both of those teams might yet win a championship—Philadelphia is a playoff regular now—but there is a cost to tanking. Players go for stats instead of wins. They think being the best player on a mediocre team is good enough. So much goes into building a winning team, and a team that tanks gives up on most of it.

“Player development, the work we put in in practice, the work we put in in film, the eye-to-eye conversation that we have … if we’re tanking, none of that applies,” Haslem says.

Adebayo was a limited offensive player at Kentucky, but the Heat recognized his competitiveness and potential. Duncan Robinson struggled to guard better athletes in college, but the Heat saw a guy that worked himself up from Division III Williams to Michigan. There is some luck in finding players, but there is no luck in developing them.

The Heat might save cap space (as they did for James and Bosh) or let an older player leave via free agency. But the organization never stops searching for ways to win. Players who get drafted by Miami, or sign with the team, are told right away, by agents and friends in the league: You better be in shape. Training camp will be brutal. Practices will be tough. Standards are uncompromising.

Tanking sounds smart. It can even work. But people underestimate how hard it is to pull off. In the lottery era—35 years now—only three No. 1 picks have won a championship in their first stint with their original teams: Tim Duncan, David Robinson and Kyrie Irving. Robinson did it only with Duncan. Irving did it only because LeBron James returned to Cleveland, and James did that largely because he happened to grow up in Akron, Ohio.

The Heat take the opposite approach of a lot of NBA teams: They trust that their culture will bring stars to them. This can work by developing enough young players to package for a star, or by maintaining a competitive enough team to attract a player like Butler. One way or another, they have probably acquired more stars in the last 25 years than any team in the league: James, Wade, Bosh, Shaq, Alonzo Mourning (twice), Tim Hardaway, Butler. They all had different skill sets and played different styles. But any one of them could have said what Butler said Tuesday, to explain the team’s stellar fourth-quarter play:

“I don't think it's just execution. I think we're in really, really, really good shape … whenever you're not tired physically, you can concentrate. You can remember plays. You can do this, and you can do that.”

Haslem does have friends on other teams, by the way. But they pretty much all played with him on the Heat.

“If you leave this team, and we built a bond on this team, then you’re considered my brother. Guys I have had that bond with—LeBron and the Shaqs and those guys—those are brothers to me now. We won together, we bled together, we cried together. Outside of that, I don’t have no friends on other teams.”

Playing for the Miami Heat is different. It’s harder, generally, but Haslem says, “Name something that’s worth having that’s not hard. Name something that’s worth having that’s not worth sharing with the people you work hard to gain it with. … One thing I tell these guys: It might not be here. Because of the way the business thing works out, it might be somewhere else. But I still want you to be successful. These things are going to apply wherever else you go.”

If the Heat had done what many pundits said they should have done four years ago—tank, or at least do a complete rebuild—they would probably not be in the Eastern Conference finals again. Adebayo would not be here, making that block. Butler would not have chosen to go to Miami.

Maybe the Heat would have young talents like Tyler Herro and Kendrick Nunn. But without Dragic, who would show them how to win? The Heat did not trade for Dragic because they thought he was the next Michael Jordan. They acquired him because he belongs on the Heat. As Spoelstra said Tuesday, “A lot of the general fans out there don't realize what a competitor he is and how he has been his entire career. … You need guys that know what it's like, how difficult it is, and particularly when we have young players that you’re relying on, you need veteran, experienced winners that can settle you, and that's who Goran is.”

A lot of teams talk about building a culture. The Heat built one 25 years ago and still have it. It is paying off now, more than the vast majority of top-five picks pay off. “Each game, each series, there's so many different things that are going on and you have to find different ways to impact winning,” Spoelstra says. “We have a lot of guys that understand that concept.”