Shaq and Kobe (and Not Glen Rice) and the Dawn of the Post-Showtime Lakers

Excerpted from Three-Ring Circus: Kobe, Shaq, Phil, and the Crazy Years of the Lakers Dynasty, by Jeff Pearlman. Copyright © 2020 by Jeff Pearlman. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

The Utah Jazz arrived at the Staples Center on Feb. 4, 2000, at the seemingly perfect time to take a baseball bat to the knees of a wobbling Lakers franchise. Phil Jackson wasn’t happy with Kobe Bryant. Bryant wasn’t happy with Shaquille O’Neal. Nobody was happy with the one-foot-out-the-door Glen Rice. “We were at our bottom,” recalled Rick Fox. “Sometimes, in the course of a season, you wonder if maybe this just isn’t going to work. That’s where we were.”

Then everything changed.

The Jazz began the game by shooting 1 for 14—brick after brick after brick. Some of this was fatigue (one night earlier, Utah had hosted Milwaukee), but most was attributable to the genre of suffocating defense Jackson had preached throughout the season. Bryant, too often an offense-only ball hog, was all over the court. O’Neal, never pleased by the sight of Jazz center Greg Ostertag, swatted away five shots—several violently. Los Angeles forced 14 first-half turnovers, resulting in 21 points. After one quarter, the Laker lead was 33–14. At halftime it was 56–21. “We pretty much did what we had to do, and we came out with a lot of energy,” O’Neal said afterwards. “We kind of needed this game.”

The final score, 113–67, was greeted by America’s sportscasters as some sort of misprint. Was that 87? Maybe 77? “It’s just one game,” Stockton said, following his 14-minute, 2-point night. “You find out a little bit about yourself after something like this.”

Indeed.

Three nights later, the Lakers triumphed again, this time a 106–98 victory over Denver. Then they won again, a 114–81 takedown of Minnesota. Then they won again—88–76 at Chicago. And 92–85 at Charlotte. And 107–99 at Orlando. Before long, the same franchise that had been on the verge of a collapse was piecing together a breathtaking 19-game winning streak. The talk about trading Rice—dead. The turmoil—shelved. The Lakers were the hottest team in basketball, a turnaround powered by talent trumping discord and (as always) the presence of the world’s greatest post player.

Throughout his first seven years in the league, O’Neal had been both the NBA’s most awe-inspiring and most maligned presence. By now, wasn’t he supposed to have a championship ring? At least one? O’Neal was a dominating force. He was an awful free throw shooter. He made teammates better. He was an awful free throw shooter. The media loved him. He was an awful free throw shooter. O’Neal had shot 59 percent from the line as a rookie with Orlando in 1992–93, and it was presumed, with time, he would get better. Only he never did. Excuses were made—oversized hands, fatigue, nerves, anxiety, the lasting impact of a childhood accident that had resulted in a broken wrist. Every year it seemed a new free-throw-shooting expert would be brought in to change the world. Once, a University of South Florida–St. Petersburg American foreign policy professor named Dennis Hans mailed Kupchak a series of articles he’d penned on O’Neal’s problems at the line. “One day I got an e-mail from Mitch, and he told me he passed my writing on to Phil and Shaq,” Hans recalled. “He made a little progress and I felt good about that. But it didn’t last.” Another time, the Lakers enlisted a private shooting coach, Ed Palubinskas, who diagnosed O’Neal as overly stiff and intimidated by the rim. Rick Barry, the retired Hall of Famer who shot free throws underhanded, to the tune of an 89 percent success rate, suggested aloud that O’Neal, too, shoot underhanded. (The big man wouldn’t dare.)

The only diagnosis—the correct diagnosis—belonged to Derek Harper, the veteran guard who had played with the Lakers in 1998–99. “He didn’t work at it hard enough,” Harper said. “That’s the simple truth. Anyone who works on free throw shooting can become at least a decent free throw shooter. Shaq was one of the best players to ever step on a court. But he didn’t devote himself to something he needed to devote himself to. He was all about power and force. Not free throws.”

Two decades removed, Harper recalled a 1999 game against Seattle that had gone down to the wire. Coming out of a fourth-quarter time-out, Kurt Rambis drew up a play for O’Neal. “We’re walking back onto the court and Shaq goes, ‘What am I supposed to do? Who is that play for again?’ ” Harper said. “I was like, Oh, he doesn’t want the ball because he might get fouled. I told him to get the ball right back out to me. I’d take care of it. It’s incredible—someone of that stature to come out of a timeout and not want the ball.”

There was a growing concern that, toward the ends of tight games, opposing coaches would foul O’Neal and place him at the free throw line. Jackson always felt the threat lingering, as did Bryant—who simply did not understand (and wondered aloud) how a man with so many skills couldn’t hit six out of ten unencumbered shots. During the streak, though, the Lakers came up with a temporary solution: Beat the snot out of opponents so they’d never have reason to place O’Neal at the stripe. Over 19 games, Los Angeles’s margin of victory was an average of 14.1 points. The close contests weren’t even that close—often the margins got tighter only late in the fourth quarter, when Jackson rested his starters.

On March 6, O’Neal celebrated his 28th birthday by—in the words of the Los Angeles Times’s Lonnie White—ripping “through the Clippers’ collection of big men as if they were wet food stamps,” en route to 61 points and 23 rebounds in a 123–103 win. Upon arriving at the Staples Center three hours before tipoff, O’Neal was told by the Clippers staff that his request for extra seats for family members had been denied. If he wanted his relatives to attend, he’d have to pay just like everyone else. O’Neal couldn’t believe it. This was his building. His court. “Don’t ever make me pay for tickets,” he said afterwards. “Ever.” Before tipoff, he had pulled aside point guard Derek Fisher and said, “Man, can a brother get 60 on his birthday?” Translation: Get me the ball, and get it to me often.

Fisher nodded. “Absolutely,” he said. “Let’s make it happen.”

O’Neal would play 19 NBA seasons, but never quite at the level of 1999–2000. He averaged 29.7 points, 13.6 rebounds, and 3 blocks, and set a career high in assists (3.8). He was in the best shape of his life, desperate to please a new coach with a track record. “Shaq is in great condition,” Brian Shaw said late in the year. “He’s blocking shots and rebounding like never before. I played with him for three years in Orlando, and he didn’t get after it on defense like this.”

The Lakers finally lost on March 16, dropping a 109–102 nail-biter at Washington. But two games later, something happened that both pleased Jackson and solidified the Lakers—these Lakers—as a different breed than their immediate predecessors. On March 19 the team returned to California to host the Knicks, a legitimate title contender whose coach, Jeff Van Gundy, had little good to say (or think) about his Los Angeles counterpart. Before accepting the Lakers job, Jackson had been in light discussions with the Knicks, and Van Gundy rightly believed it crossed a line. As Del Harris repeatedly noted, one doesn’t vie for a job held by a peer.

Even without any hostility, the Knicks weren’t a team to mess with. Their roster was a Who’s Who of NBA brawlers. Larry Johnson, the 6-foot-6, 250-pound power forward, regularly dropped opponents to the floor. Latrell Sprewell, the athletic small forward, had famously choked his head coach, P.J. Carlesimo, two years earlier. A backup power forward named Kurt Thomas was widely considered the most physically intimidating (non-Shaq) man in the league, and Patrick Ewing, the center in his 15th season, still possessed a scowl that froze boiling water. The hardest rock on the roster was also one of the smallest—6-foot-3, 195-pound point guard Chris Childs.

“Chris took no s---,” said Jayson Williams, his teammate on the Nets. “He was small, but he played big.”

The one thing Childs had no patience for was arrogance. In Kobe Bryant, he saw arrogance. He liked nothing about the kid, despised how he acted as if he walked on air and played as if he were better than the men who had been around far longer.

That’s why, in the third quarter of Knicks-Lakers, Childs took particular exception to Bryant twice elbowing him in the head as he dropped back on defense.

“Did you see that?” Childs whined to Ted Bernhardt, the referee. “Are you gonna do something about that bitch and his bulls---?”

Bernhardt shook his head.

“Okay,” Childs said. “No problem.” He leaned into Bryant and said, “I don’t mind elbows from the neck down. But do that to my head one more time, young fella, and it’s on.”

Bryant laughed. “You ain’t gonna do s---,” he said.

The Laker stood 6-foot-6, 210 pounds. He was taller, thicker, more muscular. But, across the league, few found Kobe Bryant even slightly intimidating. Seconds later, Bryant elbowed Childs again. It was mild, but enough was enough.

“He hit me with a chicken wing,” Childs said. “I hit him with the twopiece and a biscuit.”

Childs drew back his forehead and brushed it into Bryant’s face. Momentarily stunned, the Laker paused, then came back with a meek forearm to the face. (“Pussy shots,” Childs recalled.) Childs fired off a straightaway right and a left cross, both of which connected with Bryant’s cheek. Finally, with Bryant unleashing a fury of punches (none of which connected or even came close to connecting), Bernhardt stepped in and broke the men up. As Jim Cleamons, the assistant coach, dragged him away from the scrum, Bryant scrapped and clawed and screamed for more of Childs. “F--- you!” he bellowed toward the Knick. “F--- you, pussy!” Moments later, in the tunnel leading to the locker room, Bryant made another move at Childs, but to no avail. When asked about the exchange, Childs told Marc Berman of the New York Post, “Tell him I’m at the Four Seasons, Room 906.” (He was not inviting Kobe Bryant over for room service and a movie.)

Both players were ejected in the 106–82 Los Angeles win, but it was what happened next that felt remarkable. Rick Fox barked at Childs as he left the court. O’Neal shoved Ewing. Jackson scowled at Van Gundy. In the locker room afterwards, one Laker after another whispered into Bryant’s ear, assuring him they all had his back. “That’s our little brother right there,” Fox said. “As big brothers, you don’t let somebody pick on your little brother.”

“Everyone knows Kobe’s a clean-cut guy,” O’Neal added. “But he had somebody punching in his face, he had to do something about it. I was just trying to protect my little brother. If something crazy would happen, I would defend him . . . But Kobe’s a tough kid, he protected himself.”

The next morning’s Miami Herald featured the headline FIGHT MARS LAKERS WIN OVER KNICKS. Only, for Los Angeles, the fight marred nothing. Ever since Bryant arrived in the league four years earlier, Laker coaches and administrators had tried everything to make him part of the team. But here, in standing up to one of the NBA’s feistiest players, perceptions had changed. Bryant was suspended one game and fined $5,000, and it was well worth the cost. He would never be fully embraced, for he was not embraceable. But as the Lakers headed toward the playoffs, they were—at long last—unified.

“Thanks to me,” Childs said years later. “Me and my stupid temper.”

***

The Lakers wrapped the season with an NBA-best 67-15 record, and while O’Neal (29.7 points per game), Bryant (22.5 points per game), and Rice (15.9 points per game) stood out on the statistical sheets, the key was Jackson. The veteran coach somehow kept a roster overflowing with egos and arrogance in one piece; somehow convinced O’Neal to ignore Bryant’s cockiness; and somehow convinced Bryant to accept life in the shadow of a larger-than-life big man. He used Rice wisely, leaned on veterans like John Salley and Ron Harper to keep the locker room happy, forbade the hazing of rookies. “He was the greatest studier of people I’d ever been around,” said Salley. “He knew exactly which buttons to push.” In what, decades later, remains one of the more impressive tricks in modern coaching history, Jackson’s staff included Kurt Rambis, his predecessor on the sideline. It is one of the few times a new coach dared employ an exiled coach, but Jackson made it work. “It wasn’t easy at first,” Rambis said. “I felt on some level he took a job that should have been mine. But I came to like Phil, Phil came to like me. We had trust.”

The Lakers opened the playoffs by beating the eighth-seeded Kings in five games, then moved on to play the overmatched Suns, who predictably fell, four games to one. It was during the series with Phoenix that two distractions caused Jackson to silently question his team’s focus.

First, on May 9, O’Neal was named the NBA’s Most Valuable Player. He was, beyond debate, the league’s best player, and led the NBA in both scoring and field goal percentage. Yet while the initial reaction was unbridled giddiness (“The first thing I did was call my mother and father,” he said. “My father started crying”), that changed when it was learned that 120 of 121 voters had selected O’Neal first. Yes, the 99.2 percent was the highest in league history. Yes, his 1,207 points dwarfed the 408 of Minnesota’s Kevin Garnett, the runner-up. But how did someone fail to place O’Neal atop his ballot?

Within hours, the promised confidentiality of MVP voting was set aside and the world learned that Fred Hickman, the veteran CNN/SI anchor, had voted Philadelphia’s Allen Iverson first and O’Neal second. The backlash was fierce—from the Laker players (said Robert Horry, “I heard some guy at CNN didn’t vote for him. Did he ever play?”), from West (“God, I feel sorry for the guy who didn’t vote for him”), from media members (Fox’s Marques Johnson: “What happened? Some of Allen Iverson’s boys had his daughter tied up in a Brooklyn basement, there was some extortion going on?”).

“It was bad,” recalled Hickman. “To this day I don’t know how my name got out, because the vote was supposed to be anonymous. I was Steve Bartman before Steve Bartman. That reaction was really intense. Really angry. I was getting threats, which was a first for me. Threats? All because I thought Iverson was more important to his team than Shaq was to his.”

O’Neal bit his tongue and said little. Years later, however, he admitted that the anger was real. “Do I hold a grudge about that? Yeah—I do,” he said. “Some f---ing dickhead kept me from being the first unanimous MVP. Some asshole who doesn’t know s--- gives his vote to Iverson and f---- up history. I never forgot that.”

The hullabaloo passed, but days later an even bigger bombshell hit the Staples Center: Kobe Bryant was engaged.

To be married.

To another person.

With a pulse.

Really.

The Associated Press was first to report the news, and few Lakers believed it. For four years, Bryant had been a brick wall when it came to his personal life. Other members of the team were well-known partiers and womanizers, and though this was no longer the 1980s, when females lined the lobbies as Magic, Worthy, and Co. came to town, the Laker players hardly had to work to acquire late-night company.

Bryant’s personal life, though, was pure mystery. The last anyone heard of him dating someone had been in the summer of 1996, when he was accompanied to the Lower Merion senior prom by Brandy Norwood, the chart-topping pop singer, whom he (ahem) didn’t actually know.

None of his Laker teammates could believe the engagement was happening. They had never seen this girl before. Had certainly never seen Kobe Bryant with a girl before. And now he was engaged to be wed? “Bryant has always struck me as mature beyond his years,” wrote Dana Parsons in the Los Angeles Times. “To give up groupies at age 21 is laudable, and one hopes he can pick a bride as well as hit a game-winner.”

Eventually, the relationship—consummated in an April 18, 2001, wedding at St. Edward the Confessor Catholic Church, in Dana Point—would drive a wedge both within the Bryant family (none of Bryant’s relatives attended, and Pam and Joe moved back to Philadelphia) and within the Laker family (a grand total of zero teammates and coaches were invited).

But that was a ways off.

First, Los Angeles had to survive the biggest challenge of the year.

***

Heading into the Western Conference Finals, the Portland Trail Blazers didn’t give a crap about Fred Hickman’s MVP vote, and they certainly didn’t give a crap about Kobe Bryant’s engagement. They weren’t interested in Phil Jackson’s Zen teachings, Glen Rice’s trade talk, Rick Fox’s marriage, or Robert Horry’s outside shooting.

No.

The Portland Trail Blazers cared only about kicking the snot out of Los Angeles.

This was personal.

For far too long, the Blazers existed as mere gnats to the Laker lion. The two teams, located 962 miles apart and situated side by side in the Pacific Division, both featured storied histories, featuring huge names and heady days. Yet in an Annie Oakley–Frank Butler modus operandi, anything the Blazers could do, the Lakers could do better. The Blazers’ all-time greatest center was Bill Walton, the UCLA legend. The Lakers’ all-time greatest center was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the UCLA icon. The Blazers’ 1980s superstar was Clyde Drexler, a wonderful player. The Lakers’ 1980s superstar was Magic Johnson, a transcendent player. The Blazers proudly hung the 1977 NBA championship banner from the rafters. The Lakers proudly hung the 1972 NBA championship banner from the rafters. And the 1980 championship banner. And 1982. And 1985. And 1987. And 1988.

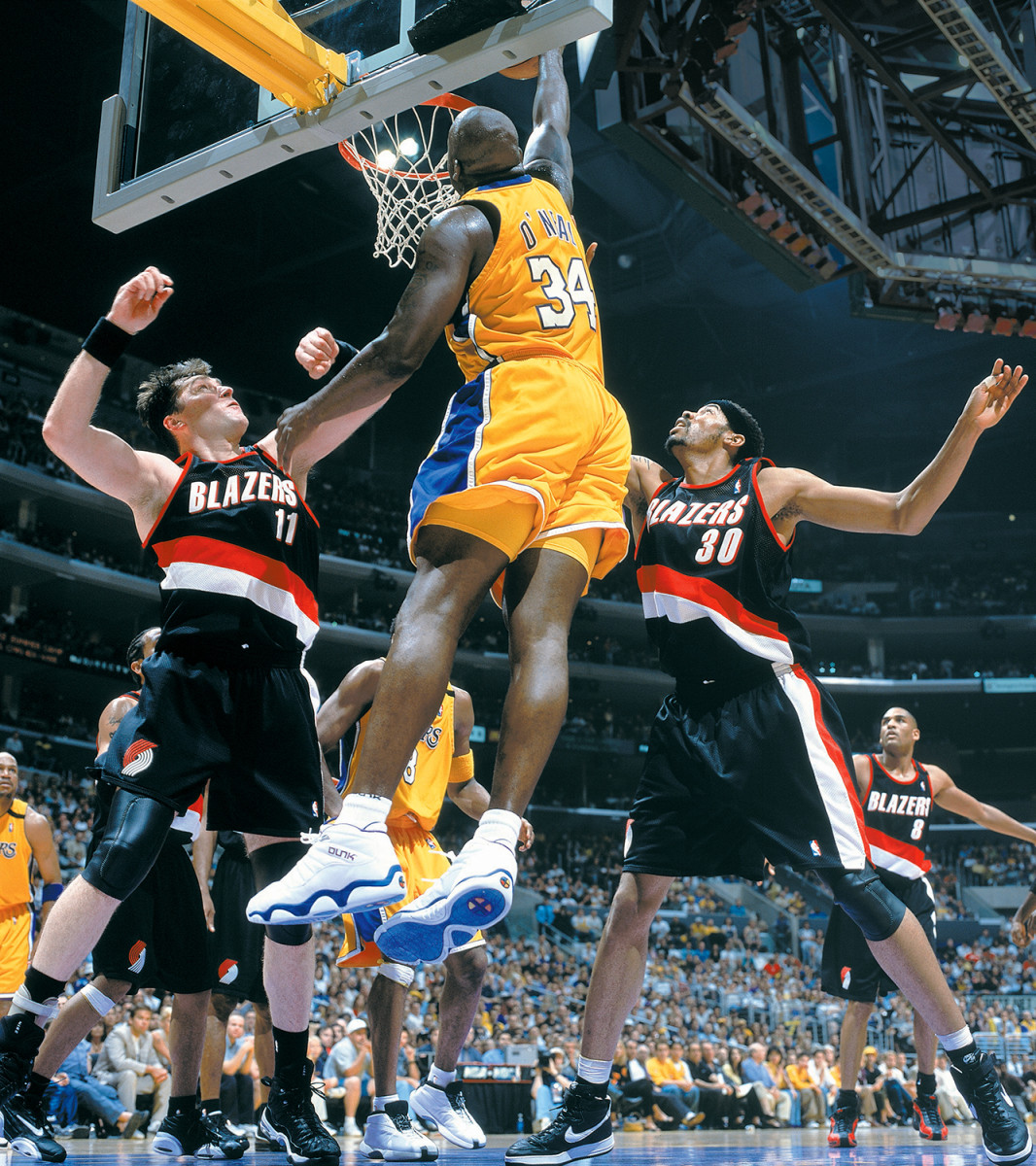

Now, entering the series, the Lakers were once again expected to triumph. They were the No. 1 overall seed, facing a third-seeded Portland squad that had won eight fewer regular season games and lacked anyone of O’Neal’s physical stature. Yet, unlike top-heavy Los Angeles, the Blazers’ $73.9 million roster was uncommonly deep. Mike Dunleavy, the veteran NBA coach, regularly used nine of his players, and in forwards Rasheed Wallace and Scottie Pippen and center Arvydas Sabonis he had at his disposal the league’s best frontcourt.

“We were the better team,” recalled Antonio Harvey, a Blazer forward. “Yes, they had Shaq and Kobe, and those guys were fantastic. But, top to bottom, we were far more skilled. I was pretty sure we were winning.”

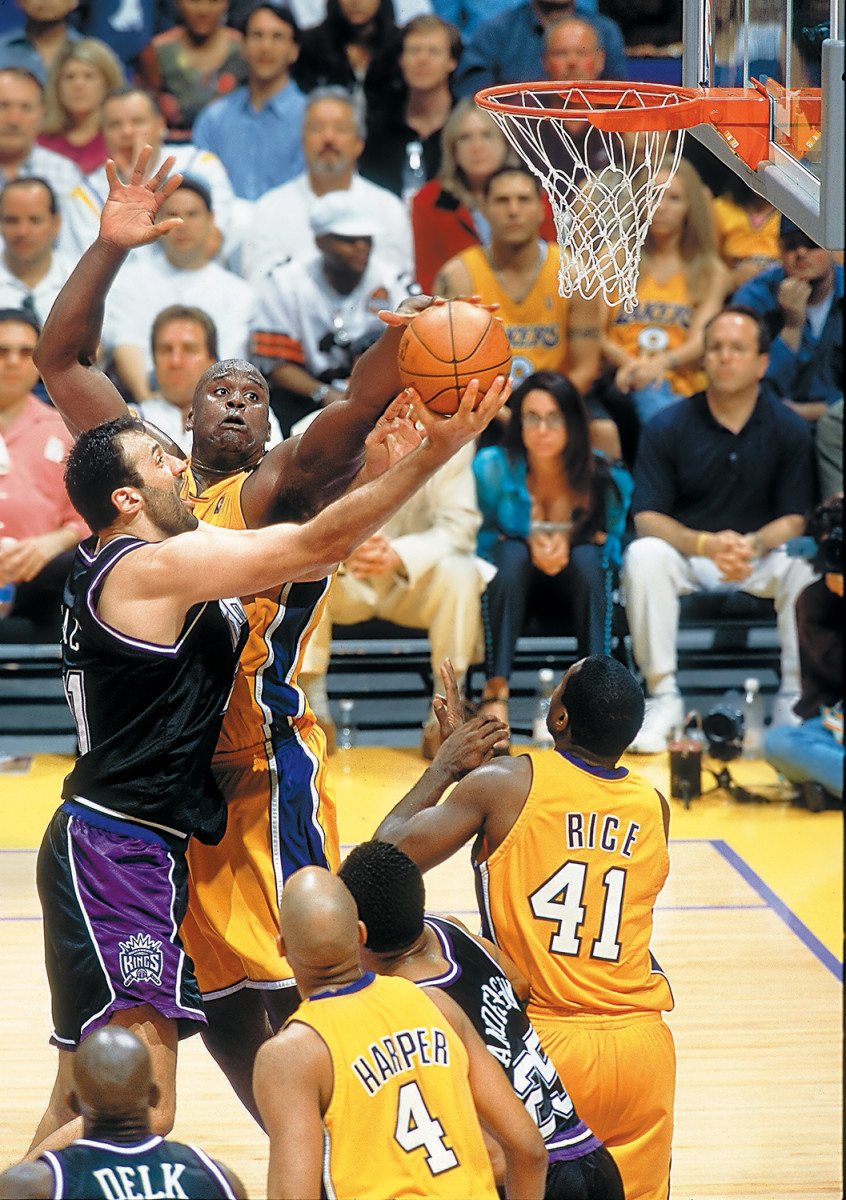

The series began on May 20 in Los Angeles, and the Lakers destroyed the Blazers, jumping out to a 21-point halftime lead en route to the 109–94 win. The game itself was an exercise in frustration and, for the 18,997 fans inside the Staples Center, boredom. With 5 minutes, 29 seconds remaining in the fourth quarter and his team down 13, Dunleavy had his men commence the infamously named and executed Hack-a-Shaq—aka Foul O’Neal whenever he touches the ball and hope he bricks his free throws.

The tactic failed. O’Neal connected on 12 of 25 fourth-quarter attempts, shattering the playoff mark for free throw tries in a quarter, finishing with 41 points total, and causing the Portland players to look toward their coach with exasperated glares. “Anything that works, I’m fine with it,” Pippen said with a sigh. “Shaq did what he had to do. He stepped up and made them, which makes everything look kind of stupid.”

Two nights later, Portland annihilated the Lakers, 106–77, setting up what would go down as one of the all-time classic playoff series. Sabonis, the Portland center, was 35 years old and far past his prime. A decade and a half earlier, while the Kaunas, Lithuania, native had starred in Europe and for the Soviet national team, most basketball experts had placed Sabonis alongside Patrick Ewing, Hakeem Olajuwon, and Ralph Sampson for bigman greatness. He was quick and strong and passed like a mountainous Pearl Washington. By the time he arrived in the NBA for the 1995–96 season, though, Sabonis was hobbled by arthritic knees and a battle-wounded body. “He was so talented,” said Kerry Eggers, who covered the Blazers for the Oregonian. “He couldn’t run anymore, but he was one of the very few NBA players who matched strength with Shaq.”

In Game 3 at Portland, Dunleavy kept Sabonis on the court for 35 minutes, hoping (praying) he would wear down O’Neal with unyielding physicality. For a spell, it seemed to work. The Laker center ended the first quarter with no points or rebounds, and the Blazers led by 14 in the second quarter and 10 at halftime. Sabonis wasted no chance to give O’Neal an elbow to the ribs, a forearm to the chest. Inside the locker room, a furious Jackson pulled his star aside and said, bluntly, “You’re playing terribly.”

“[He] said I wasn’t being aggressive enough,” O’Neal said. “He was right.”

Unlike Bryant, who did not need a coach’s anger to get him going, O’Neal could be a Porsche without its engine. He required an enemy. A rival. Someone to piss him off. For years, he told people that Ewing was a jerk who treated him rudely. He told people Alonzo Mourning hated him. He told people David Robinson, the Spurs’ sublime center, had refused to sign an autograph for him as a teenager.

This time, still licking his wounds from the Jackson tongue-lashing, O’Neal convinced himself that Sabonis was a world-class whiner who had the officials’ ears. “It’s kind of funny to me,” he later recalled, “how a guy 7-foot-3 who weighs almost as much as me starts crying to the officials.”

The second half was all O’Neal, who scored 18 of his 26 points while gathering 12 rebounds. What he did best was beat down Sabonis. O’Neal had punished his rival the way he punished all his rivals: with blunt force trauma and excessive weight. With 13 seconds remaining and Los Angeles up 93–91, Portland guard Damon Stoudamire drove through the lane past Bryant, then kicked it out to Sabonis, who stood just inside the three-point line. Portland’s center pump-faked, sending O’Neal flying, and dribbled glacially one time toward the hoop. As the center released the ball, Bryant—eight inches shorter—leapt through the air and swatted it away.

With that, the clock expired, Lakers players swarmed Bryant in a congratulatory group hug, and the team held a two-games-to-one series lead. Inside the Los Angeles locker room, there was little doubt that the Blazers were about to roll over and die. “Now the pressure’s on Portland,” Jackson said. “Because if we put another notch in our belt Sunday, they’re really at death’s door, and they know it.”

He was speaking to Chuck Culpepper of the Oregonian. Truly, though, he was speaking to the Blazers—a group of uber-talented players who, with the exception of Pippen, were better known for choking than celebrating. There’s something draining about hearing how gifted you are, then failing to capitalize on that gift. Steve Smith, the Portland shooting guard—no rings. Stoudamire, the point guard—no rings. Detlef Schrempf, an elite scorer for 16 seasons—no rings. Sabonis, the giant with the soft touch—no rings. Wallace, feisty but productive—no rings. Dunleavy, the head coach in his ninth season on a sideline—no rings. “You have to have something to show for your efforts,” Fox said. “Otherwise it’s just rhetoric.”

Yet these Blazers weren’t those Blazers. After losing Game 4 at home, 103–91, to go down three games to one, they somehow staged a remarkable bounce back, winning the next contest in Los Angeles, 96–88. Three days later, back home at the Rose Garden, Portland won 103–93, evening the series at three games each. O’Neal looked like a deadwood ghost of his MVP self, scoring just 17 points, lumbering up and down the floor, hitting a putrid 3 of 10 free throws. For the second-straight game, he was barely existent in the fourth quarter. He scored just 4 points, taking a single shot—a measly four-foot hook. Over the game’s final 5:25, he did (almost literally) nothing but watch as players whizzed past. When asked afterwards about his partner’s ineffectiveness, Bryant could barely conceal his irritation. “There was a lot of bumping and shoving going on,” he said. “But Shaq’s a big, strong guy. He’ll be ready to play on Sunday.”

Jackson wasn’t so sure.

When the game ended and the media cleared out, he sat down with his coaches and wondered—truly wondered—whether the series was a lost cause. In all those years with Chicago, Jackson knew, come crunch time, Michael Jordan would be there to carry the team.

But now, the coach wondered, did that even exist?

Did the Lakers have what it took to survive?

***

On April 7, 2001, slightly less than a year after the Lakers-Blazers series, Shaquille O’Neal authored a book titled Shaq Talks Back. It sold fairly well and spent a bunch of weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, but it is hardly ranked alongside Jim Bouton’s Ball Four or Pat Jordan’s A False Spring as a classic athlete tell-all. Like many books, it came, it went, it found itself selling for $1.98 on Amazon.

Which is a shame, because over the course of 276 pages, O’Neal—who teamed up with Mike Wise of the Washington Post on the project—bared his soul in unusual and remarkable ways.

O’Neal wrote, at length, about his disdain for Bryant, his mistrust of Del Harris. He touched on insecurities, fears, plagues, heartache. Page after page, it’s O’Neal speaking truth to power in ways very few athletes ever do.

Nearly two decades after the release, O’Neal told a reporter (me, Jeff Pearlman!) that the book was a mistake—that he’d said too much and the backlash wasn’t worth the paycheck. “I didn’t even read it,” he admitted. “I just didn’t like the reaction.”

In particular, O’Neal might have been referring to page 229, when he admitted that, following the Game 6 defeat to Portland, he was quite certain the Lakers were about to fold. Wrote O’Neal: “Walking off the court after Game 6, I didn’t feel good at all . . . I was remembering all those people who kept badgering me about the Lakers not having a killer instinct. As much as I hated to admit it, they were right. It was the truth. We couldn’t put the nail in the coffin.”

There have been times throughout his life when O’Neal seemed to enjoy exaggerating things for the sake of explosiveness, headlines, bullet points. He was P.T. Barnum in a basketball jersey, and the rap albums, grade-D films, T-shirts, hats, commercials, self-appointed nicknames—Shaq Fu, Shaq Diesel, the Real Deal, the Big Daddy, the Big Aristotle, the Big Galactus, Mayor McShaq, Wilt Chamberneezy, M.D.E. (Most Dominant Ever)—were all part of the show. “He used to say he had 52 moves on the lower box,” said Andy Bernstein, the Lakers’ photographer.

This, though, was no act. The man was genuinely concerned that his NBA résumé was about to include the harrowing update EIGHT SEASONS, NO CHAMPIONSHIPS.

Truth be told, to be a Laker—any Laker—in the aftermath of the 103–93 setback was to be a man plagued by a severe sense of self-doubt.

“Did I think we were going to win that seventh game?” John Salley, the 12th man and 11-year vet, asked decades later. “Honestly, I don’t think so.”

“It was,” added Rice, “not looking very good.”

The Portland Trail Blazers entered the building determined to put the Lakers to sleep. Historically speaking, seventh games tend to go to the team with the greatest depth. It makes sense—you’re beaten down, you’re worn out, legs are Jell-O, feet are hot coals, minds are pudding. If there are two or three or (gasp!) four guys who can come off the bench and do damage, the odds shift to your favor. Why, a mere 13 years earlier, Los Angeles had made a February trade with San Antonio, adding (longtime Portland) forward Mychal Thompson to a somewhat thin bench. The result? An NBA title.

These Blazers were stacked. Perhaps that’s why, when asked about Game 7, Dunleavy told the assembled media, “The team that plays the full 48 minutes is going to win.”

The words would prove prophetic.

A sellout crowd of 18,997 entered the Staples Center, with tickets going for as much as $1,200 in the secondhand market. The Lakers had last reached an NBA Finals series in 1991, a short span for most cities but an eternity in a metropolis spoiled by success. As the starting lineup for the home team was introduced—first Bryant and Harper at the guard slots, then A.C. Green and Rice as forwards, then O’Neal in the middle—the noise was deafening. The Staples Center lacked the acoustical oomph of the now shuttered Forum, and sound tended to get lost in the high ceiling. But here, at this moment, it was as loud and explosive as a stadium could be.

This was the return of Showtime.

The return of the dynasty.

The return to NBA dominance.

The . . . worst.

The opening tip went to Portland, and seconds later Wallace—lithe, quick, confident—hit a turnaround jumper over the earthbound A.C. Green. Harper answered quickly with his own jumper, and as he bounded back down the court, he bobbed his head, skipped backwards. In hindsight, it can be read two different ways. Either:

A. “Yeah, we’re ready!” Or:

B. “Guys, come on! Wake up!”

It was B.

Los Angeles needed to wake up. Portland opened up a 23–16 lead, and at halftime the advantage was 42–39. Which, while only 3 points, felt closer to 30. Much had gone right for Los Angeles (Bryant had 12, O’Neal 9), and they still trailed. In the locker room, Fox—the emotional leader of the squad—went off. “Here we go again,” he said, standing in the center of the rectangle. “Everybody’s got a blank look on his face. So what are we going to do about it? Are we going to let the referees dictate the terms of the game? Are we going to be passive and get blown out again? Or are we going to stand up on our own feet? Are we going to provide support for each other?”

Tex Winter, lingering alongside Jackson, said, “Phil, you better tell him to shut up.”

“No,” the coach replied. “Somebody’s got to say these things.”

In a movie, the Lakers charge back onto the court and dominate. A John Williams song plays, Bryant soars through the air, O’Neal swats shot after shot.

This was no movie.

Portland exited its locker room looking like the 1995–96 Chicago Bulls. Powered by 10 points from Steve Smith and 6 from Wallace, they went on a 21-to-4 spurt. The boos rained down. Horry, the veteran with two rings, looked numb. What the hell is going on? Fox recalled thinking. Who are we? Wallace, in particular, couldn’t be stopped, spinning past O’Neal (who was scoreless in the third period) on multiple moves to the hoop. “Rasheed Wallace is working harder for better position than Shaquille O’Neal,” Bill Walton, broadcasting the game for NBC, noted. “He knows he’s gonna get the ball. Shaq works hard and doesn’t get it. Rasheed does.”

With 20 seconds remaining in the period, Pippen hit a three-pointer over a lunging Shaw, giving his team a game-high 71–55 advantage. The arena’s occupants let loose a collective groan and Walton said, in a rare dose of seriousness, “The Lakers need something big here to try to fire the crowd up over the quarter break.”

Shortly after the words were uttered, Bryant found himself holding the ball atop the key, Bonzi Wells in his way, Pippen drifting in from his right. Everyone knew the kid would shoot, because, with history as a guide, the kid always shot.

Dribble.

Dribble.

Dribble.

Off to the side stood the most nondescript of Lakers. At 6-foot-6 and 190 pounds, with sleepy eyes and a longish neck, Brian Shaw wasn’t one to be noticed on or off the court. He was only a member of the team because, three days after Houston acquired him in an October 2, 1999, trade from Portland, he was unceremoniously released. The Lakers signed Shaw for a mere $510,000—chump change for a reserve with a long resume of solid play and team-first mechanisms. “He’s been a quality player in this league for a number of years,” Jackson said at the time. “He’s been down for a couple of years now and this is an opportunity to get a player . . . who can play a big guard.”

“Brian always wanted to be a Laker,” said Jerome Stanley, his agent. “He was a California kid, loved the team. When they were interested, he wanted me to jump on it. So we did.”

Shaw wound up averaging 4.1 points in 74 games and served an important role as the clubhouse peacemaker and love guru between O’Neal and Bryant. In a room overflowing with stars and established veterans, his voice carried the loudest. Part of it was the gravitas of 10 NBA seasons: Stanley refers to his client as a 1990s “NBA Zeitgeist—he played with Shaq in Orlando, played with Larry Bird in Boston, was on the Warriors when Sprewell choked the coach, was with the Celtics when Reggie Lewis died.” But it also had something to do with his status as a survivor. Seven years earlier, while a member of the Miami Heat, Shaw was at home in Oakland, preparing for a June 26, 1993, barbecue, when his phone rang. He picked up and was told—by the Nevada’s coroner’s office, in the bluntest of terms—that his mother, father, and sister had been killed in a one-car crash en route from Northern California to Las Vegas. The lone survivor was his 11-month-old niece, Brianna.

Shaw hung up and immediately called Stanley.

“They’re all dead!” he wailed.

“Who’s dead?” Stanley said.

“Everybody!” he replied. “My whole family is dead. They died in a car accident.”

Silence.

Somehow, Shaw was able to recover. He and his wife, Nikki, adopted Brianna. When she was finally old enough to ask about the tragic day, Shaw told her, “Your mommy went to live with God and left you here for me to take care of you.”

Now, seven years later, Shaw feared nothing. A bad pass? Big deal. A moment of laziness on defense? Ho-hum. A key shot with 4.4 seconds on the clock and his team down by 16 to the Portland Trail Blazers in Game 7 of the Western Conference Finals?

Bring it.

Bryant took a dribble toward the hoop, then shoveled the ball back to Shaw, who stopped, squared up, and banked a three-pointer over the outstretched arms of Wells.

The shot wasn’t a game winner, but it was, in hindsight, a game changer. As his players congregated along the sideline to begin the fourth quarter, Jackson had something important to say. “You know what,” he growled. “They’re kicking our ass. They are absolutely kicking our ass. I don’t know what’s going on, but let’s just get it over with. I’ll see you guys next year. To hell with this.”

O’Neal shook his head. “F--- that,” he said. “F--- that.”

What happened next is NBA lore. Or, put differently, the high-flying, free-flowing, confident-to-the-point-of-cockiness Portland Trail Blazers were run down by a Mack truck. Jackson told his players—begged his players—to shoot. Dunleavy had the Blazers double-teaming O’Neal, and the forced passes down low were too often being batted away. “Kobe, fire away,” Jackson said. “Brian, fire away. When you’re open, take it.”

“We started getting mad,” O’Neal said. “Kobe was mad, B-Shaw was mad. That’s exactly what we needed: that anger. That was the one time all year when they really saved my ass, because I was getting quadruple-teamed and playing like s---. I needed help in the worst way.”

“You’re talking about the ultimate warriors,” Rice recalled. “Our team was made up of guys who never gave up.”

The Blazers started the fourth quarter with Steve Smith driving to the hoop for an uncontested runner, and the boos rained down. Walton, from the booth, said, “Twelve minutes to do something in your life. This is where you just blast through all the pain, and know that if you come up big . . .”

With 10:06 left, Shaq took a pass down low from Horry and hit a layup over Sabonis. 75–62, Blazers.

No big deal.

On the next Blazer possession, Bryant emphatically swatted a Bonzi Wells shot, grabbed the ball, and pushed it up the court. Shaw, standing alone in the corner, received a swing pass from Horry and drained the three. 75–65, Blazers.

Still, no big deal.

Portland called a time-out. NBC’s microphone picked up Jackson’s sideline instructions. “Get yourself in position to shoot the ball,” he said. “And shoot good shots. Forget about Shaq. If he’s open, throw it in. If he’s not, don’t force things just to go into him. And loosen up.”

The Blazers brought the ball up-court and Pippen bricked a three-point attempt. The ball found its way into the hands of Bryant, who soared to the hoop and was fouled on the way up by Wells. Bryant licked his lips, a la Michael Jordan, and walked to the line. He missed the first free throw, then made the second. 75–66, Blazers.

Nine minutes left in the game.

Still, no big deal.

“We have the lead,” recalled Elston Turner, a Portland assistant coach. “We have veteran guys who can’t make plays—guys with a résumé of making big plays.”

The Blazers again had the ball. Wallace shot—and missed—a jumper. Wells collected the offensive rebound, passed it back down to Wallace, who shot—and missed—another jumper. Shaw gobbled the rebound, pushed the ball up-court, and passed it down low to O’Neal. He was elbowed by Sabonis, who whined, moaned, griped—and left the court with his fifth foul. This was, for the Lakers, a blessing. Portland’s center was a big, strong, physical thorn in his side. Now that thorn was shuffling toward the bench, replaced by the smaller Brian Grant (“who has been completely ineffective,” as Walton said when he entered the game).

Fox fired a three and missed, but the rebound was corralled by the suddenly liberated O’Neal, who went back up and was hacked by Wallace. O’Neal bricked the first free throw attempt, then made the second. 75–67, Blazers.

Still, eh, um, not a particularly big deal.

Only, eh, um, it was starting to feel like a big deal. The crowd was now cheering. The Portland players looked stiff. “We weren’t built for it the way we thought we were,” Antonio Harvey, a Portland reserve, said. “The only player on the roster ready for the moment was Scottie, but he wasn’t the Scottie of the Chicago Bulls, a guy equipped to carry that load when he was with Michael Jordan. Rasheed was the best player on the roster, but at that point in his life I’m not sure he was ready to carry that load. Steve Smith was a great player, but physically he wasn’t what he once was. We were an ensemble cast of former great players, but nobody was in the moment at that time.”

The teams exchanged misfires on their following possessions, and with 7:30 on the clock, Shaw casually brought the ball up the court and passed to Horry, who passed to Fox, who passed back to Shaw, who bent his knees and bricked a three. Horry somehow grabbed the rebound, dribbled out behind the three-point line, and, in a moment of laziness from Wallace, let loose a wide-open shot that floated through the air before slicing into the net. Dunleavy, nervously pacing the sidelines, licked his lips—a telltale sign of coaching anxiety. 75–70, Blazers. A hair more than seven minutes left.

“It just snowballed,” said Joe Kleine, Portland’s backup center. “It was a real s----y feeling.”

Action needed to be taken. A time-out. A substitution. Give the winded Wallace a quick breather. Get Stoudamire, stuck to the bench in favor of Wells, back on the floor. Find time for the sharpshooting Schrempf. Something. Anything.

Instead, Portland’s coach froze. Pippen misfired yet again, and Shaw stole the rebound out of Grant’s hands. When the officials called a charge on Horry, Portland was blessed with a much-needed television time-out. Los Angeles was in the midst of a 10-0 run, and the Blazers were shooting 1 for 7 in the quarter. The needed moment of rest would help the experienced Blazers regroup and . . .

Nope.

Wallace missed yet another turnaround jumper, leading to an O’Neal rebound and Bryant drifting into the lane and nailing a short jumper. The score was 75–72, with 5:40 left and everything going right for Los Angeles. “The attack came from all angles,” Jackson recalled.

During his 11 years as a Bull, Pippen was considered one of the NBA’s five or six best players—an elastic, do-everything superstar with an inevitable future in the Hall of Fame. But here, with the ball in his hands, he seemed uncertain. Having coached him for nine years, Jackson knew his former pupil’s shortcomings. Desperate to escape Jordan’s ghost, Pippen played as a man without a map. The need weighed on him. Controlled him. Now, when the Blazers required a hero, their go-to guy was anything but. Pippen passed up several possible shots, and with 5:08 left he got the ball to Wallace, who yet again misfired.

The Lakers failed to convert, and as Pippen dribbled the ball, Walton, sitting courtside, could not hide his indignation. “Slash to the hoop if you’re Scottie Pippen!” he yelped. “Forget the fade-away jumpers! Forget the double clutches!” Pippen wasn’t listening. He passed down low to Grant, whose shot was swatted away by O’Neal, then dished to Wallace, who missed another jumper. By now it was clear: Scottie Pippen did not want the game in his hands.

Los Angeles finally tied things at 75 on a Shaw three-pointer, and the building erupted as it had never erupted before. Then, moments later, it turned 1,000 times louder.

With the home team up 83–79 and 56 seconds showing on the clock, Pippen misfired on a three-pointer. O’Neal gobbled the board and Bryant was handed the ball. Guarded by the now exhausted Pippen, he charged into the paint as all five Blazer defenders collapsed around him. Then—pow!

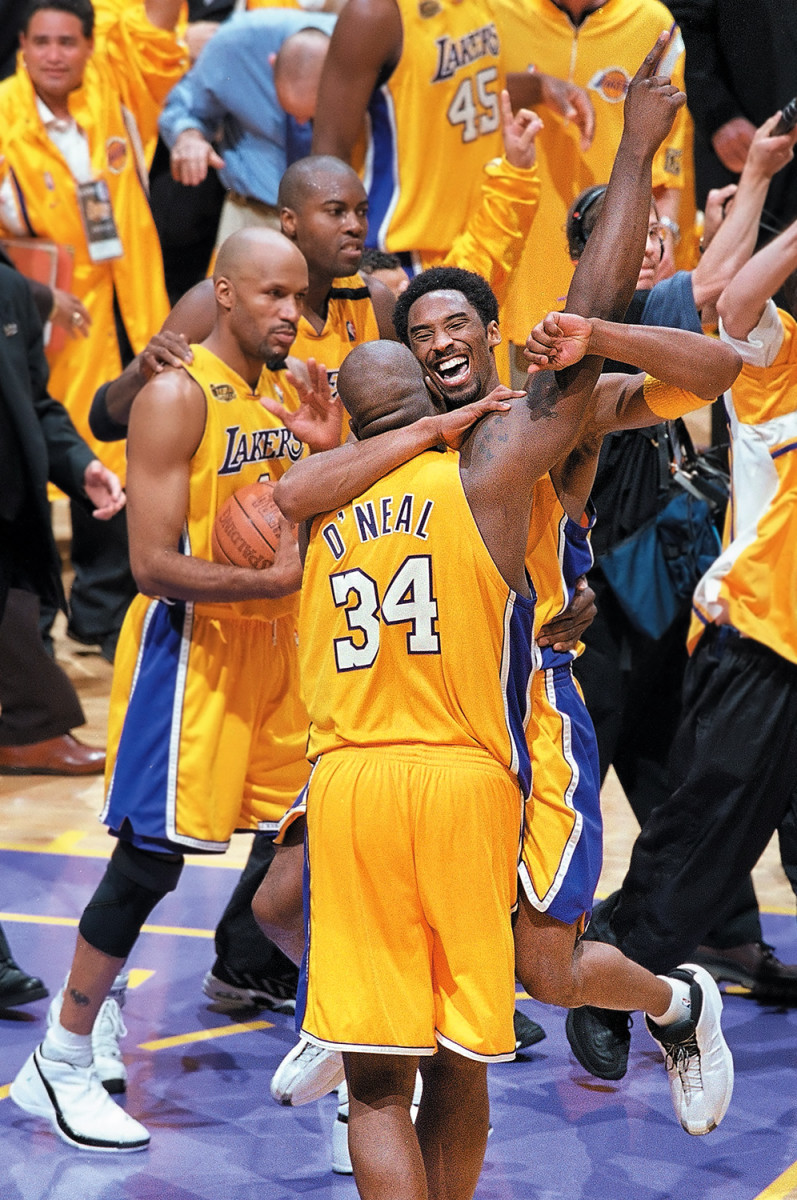

Without looking, he looped the ball toward the rim, where O’Neal soared through the air and slammed it, one-handed, over a helpless Wallace. It was athletic, explosive, dynamic, and O’Neal dashed back down the court, mouth agape, pointing toward the bench and darting past Bryant, the teammate he loathed/loved. “That was the defining moment for us,” O’Neal recalled. “For Shaq and Kobe. For the two of us. Once he did that, anything bad was forgotten. It was f---ing magic.”

Dunleavy called a time-out, but it was too late. The modest final score, 89–84, failed to tell the story of one of the most euphoric nights in franchise history.

The Los Angeles Lakers were heading to the NBA Finals.

***

Glen Rice is a nice man.

This needs to be said, because occasionally capsules in time suggest character traits that are temporary, not eternal.

So, again, Glen Rice is a nice man. He’s an attentive father, a warm friend, a person who has helped more than his fair share of those in need. “Glen was fun to cover,” said Rick Bonnell, the Charlotte Observer’s Hornets beat writer during Rice’s time there. “There was nothing not to like.”

With that out of the way, it is equally fair to note that as the Los Angeles Lakers headed into the NBA Finals, Glen Rice was a major pain in the ass.

Sure, he was glad the franchise had advanced past Portland and, sure, he was happy to be receiving the extra dough that came with the postseason success. But where were the touches? The shots? The attention? In the Portland series, he averaged but 11 points per game and a paltry 8.9 attempts. When Rice arrived from Charlotte a season earlier, he had known that O’Neal and Bryant were offensive options A and B. But he would be a B, too, right?

No.

“I didn’t need to be the Guy in Los Angeles,” Rice recalled. “I really didn’t. But I’d always had a scorer’s mentality, and they didn’t need that as much from me as the other teams. So it was . . . different.”

Unlike the Blazers, a loaded outfit with a roster of stars, the Eastern Conference champion Indiana Pacers were a largely blue-collar operation in the mold of their blue-collar coach, the legendary Larry Bird. Their small forward, Reggie Miller, was a dynamic (and loquacious) player who averaged 18.1 points, and Jalen Rose, the shooting guard best known for his time as a member of Michigan’s Fab Five, had averaged 18.2 points and emerged as a legit NBA standout. Otherwise, Indiana’s rotation was as dull as the team’s blue-and-gold uniforms. Center Rik Smits, a 7-foot-4, 265-pound beanpole, was steady. Point guard Mark Jackson, in his 13th season, was steady. Power forward Dale Davis, 6-foot-11 and strong as oak, was steady. The team won 56 games, but few inside the Los Angeles locker room felt particularly concerned.

“Playing the Pacers in the Finals was almost anti-climactic,” O’Neal recalled. “They were a scrappy team . . . but we were just better.”

The series began with Game 1 in Los Angeles, and if ever an omen existed, it was the sight of one of the Pacers’ buses stuck in rush-hour traffic en route from the team hotel in Santa Monica. By the time the vehicle—carrying Bird, Miller, Rose, Jackson, and point guard Travis Best—arrived at Staples Center, less than an hour remained before tipoff. “Reggie was a complete creature of habit,” recalled Best. “He had to get to an arena early, get all his shots up. He’d usually be waiting in the locker room while we all warmed up, because he did his work already. It was the way it had to be.”

Now, after sprinting through a tunnel and into the locker room, then changing into his uniform, then taping, then stretching, Miller had approximately five minutes to shoot. “That,” Best said, “didn’t help.”

The massacre that followed surprised no one on the Pacers. Miller, one of the great gunners in NBA history, went 1 for 16 from the field, and his team trailed for all but 1 minute and 41 seconds of the 104–87 setback. Of greater concern for Bird was O’Neal, who totaled 43 points and 19 rebounds in a methodical decimation of Smits, Davis, and Derrick McKey. When asked afterwards how he would defend himself, O’Neal laughed. “I wouldn’t,” he said. “I would just go home. I would fake an injury or something.”

The teams met two nights later, and while the score was closer (111–104), the Lakers once again exploited a preposterous mismatch. This time O’Neal was held to 40 points (with 24 rebounds), and the Pacers could merely watch and wonder how this series might possibly turn around. “We kept trying to give Shaq different looks, but it didn’t work,” said Davis. “You tried to push him away from the basket. But look at his size and look at my size. It’s like trying to move a mountain.”

The only glimmer of hope for Bird’s club came with 3:26 remaining in the first quarter, when Bryant hit a 17-footer from the right wing, then crumbled to the floor after his left foot landed atop Rose’s. This was no random mishap—the Indiana guard intentionally tried to injure his nemesis. “I’m not proud,” Rose later admitted, “and I don’t think it’s cool or cute to say, but he didn’t accidentally hurt himself.” Bryant’s ankle turned over grotesquely, and the crowd of 18,997 grew silent. Bryant was helped off the court, not to return.

Fortunately, Rice stepped up and scored 21 points, tying his playoff high. “A lot of people say I’m the third option,” he said after the game. “It was a matter of getting looks. Once I hit a couple, the confidence went up.”

Rice sounded optimistic and engaged. He looked optimistic and engaged. But then, two days later, the series shifted to Indiana, and the Bryant-less Lakers fell, 100–91. Thrust into the spotlight as the man who needed to pick up the slack, Rice appeared awkward, ordinary, and a wee bit confused. In 27 minutes, he shot 3 of 9 from the field for 7 points and watched angrily as Harper, Shaw, Fox, and Horry received more time. Rice played a total of four second-quarter minutes, during which Indiana outscored Los Angeles 30–27. “I never really got into the offensive flow,” he said later. “Once I went to the bench I never got back in it.” For much of the season, he had silently stewed in a broth of his own self-pity. Rice wanted to be the guy launching threes. Now, even when duty seemed to call, the Lakers were holding him back.

On the morning following the setback, Jackson gathered his team for a workout. Afterwards, players were made available to the media, and the normally bland Rice, whose quotes often devolved into take-one-for-the team cliché blather, longed to unload. He was tired—damn tired—of not being used properly, and if Jackson hoped to hang on to the series lead, he’d be wise to let the three-time All-Star do his thing. “I definitely think we would have had a better chance to win with me on the floor,” Rice said. “I really think I need to be in there for us to succeed . . . I’m trying to be as positive as I can. I’m not trying to be negative or be the bad apple in the bunch. I’m just asking to be involved a little more.”

When asked if he would talk to his coach, Rice shook his head. “I’m not going to him,” he said. “He’s going to do what he’s going to do.”

The words were bad. What was uttered 2,067 miles away in Southern California was worse. Bill Plaschke, the Los Angeles Times columnist, spoke with Cristina Fernandez Rice, Glen’s wife, about her thoughts on what was transpiring. Why was her insight important? Hard to say. Was it worthy of 700 column words? Also hard to say. But Mrs. Rice didn’t hold back:

Jackson has never wanted Glen, he’s always wanted somebody like Scottie Pippen, and this is his way of getting back at management for not letting him make a trade. This is Jackson’s way of showing the people on top of him who is in control. It’s crazy. Glen shined, so Jackson had to put him back in the dark again. It’s all a mind game. It’s all about control. Jackson did not get his way with the general manager or the owner about trading Glen, so who pays for it? Glen does. You have Kobe out, it was Glen’s one chance to step up and contribute to the team, and Jackson wouldn’t let him do it.

Back in Indianapolis, Rice wanted to hide. Yes, he believed everything his wife had said. But . . . did she have to say it? An already awkward coach-player relationship turned even more awkward. “I told her, ‘You can think all that stuff, but you can’t say it,’ ” Rice recalled. “Especially to a reporter.”

Coach and shooter didn’t discuss their differences or the words, and when the Lakers and the Pacers resumed the series on June 14 at Conseco Fieldhouse, Rice was still in the starting lineup, standing alongside O’Neal, Green, Harper, and a taped-up, back-from-the-dead Bryant, who’d had Gary Vitti, the Los Angeles trainer, pop the ankle into place so he wouldn’t miss what would normally be an extended amount of time.

This was Rice’s chance to prove his coach wrong. O’Neal was tired. Bryant was injured. The team was coming off a defeat and needed a boost. The Indiana fans—18,345 strong—were as loud as any in the league. Jackson, the coach always seeking a mental edge, knew Rice was hungry.

He played 39 minutes, third most on the Lakers.

He scored 11 points.

For those focused on Rice’s plight, it was a pathetic reminder of a falling star falling fast. For those focused on the Lakers as a whole, it was a night of ecstasy. Bryant’s return was startling. After hobbling onto the court, limp slight but noticeable, he scored 28 points on 14-for-27 shooting. When regulation concluded with a tie at 104, Bryant shifted to a higher gear. Or, as Peter May of the Boston Globe wrote, “This game may well be remembered as ‘The Night Kobe Bryant Came Out.’ ”

With 2:33 remaining in overtime and the Lakers up 112–109, O’Neal picked up his sixth foul, walking off the court to elated cheers. He was replaced by Salley, the 36-year-old deep reserve trying to become the first man to win titles with three different franchises. This game, Bryant thought, just became a lot more interesting. Salley had averaged 1.6 points in limited regular season action, and in the moment his job was simple: Creaky knees, sensitive feet, minimal vertical be damned—guard Smits as best he could and get out of Kobe’s way.

Three seconds later, Smits tossed an easy hook over Salley’s head. The lead was sliced to a single point.

The clock was approaching two minutes. Bryant was charged with everything. He dribbled the ball up-court, guarded closely by Miller. The crowd chanted “Dee-fense! Dee-fense!” Horry rose from the paint to set a pick, then rolled. Any point guard worth his salt dumps the ball to Horry, who was open and free. Bryant didn’t glance his way. Not for a second. He dribbled and dribbled, just as he’d always dreamed of dribbling and dribbling, then crossed over Miller before releasing a jumper from inside the three-point line. The ball soared through the air and cut through the net, and Los Angeles was up three.

The Pacers came back down and, once again, Smits scored over the outgunned Salley, who could only stare longingly toward O’Neal on the bench. With 1:34 left, the score was 114–113. The Pacers needed one stop.

Bryant had the ball, this time guarded by the old, slow, and overweight Mark Jackson. Horry liked the mismatch, and came up to set a pick. It was perfectly done, and Horry then rolled—all alone, in the way one is all alone when he has hepatitis C and is coughing uncontrollably—toward the basket. All Bryant had to do was throw an easy pass and Horry would score. But no. Bryant pulled up and uncorked another jumper that swooshed through the net. “How good is this kid?” marveled Bob Costas to NBC’s viewers.

Miller’s two free throws again sliced the lead to one, 116–115. The next time down the court, Bryant’s shot was blocked out of bounds by Smits. Rice had the ball a second later, and his air ball (yes, air ball) was grabbed by Shaw, who put it in the hoop.

Smits answered with two free throws, and the game clock read :28. There was no mystery here—Bryant would surely have the ball, and the game, at his disposal. Shaw advanced up the court, Jackson before him, and tried getting it to the star. Only he couldn’t. Miller was all over him, refusing to let Bryant get free. So, with six seconds on the shot clock, Shaw scooted toward the basket. His shot bounced off the rim when—swoosh—Bryant soared through the air and put it in the hoop, back facing the rim.

When Miller’s three-point attempt hit the front of the rim and bounced out, the Lakers had a 120–118 win and a three-games-to-one series lead. O’Neal and Bryant embraced on the court shortly after the final buzzer sounded—a big man thanking a smaller man for bailing him out. Asked afterwards about the importance of the win, Bryant, who had 8 points in overtime and could barely hide the pain of a now pulsating left ankle, was blunt.

“In our mind,” he said, “this is the championship.”

He was right.

The Pacers won the next game at Conseco in a 120–87 fluke blowout, before which members of the home team saw bottles of champagne being wheeled toward the Lakers’ locker room. (Said Mark Jackson: “That was disrespectful to us and the character we have on this basketball team.”) But there was no way Indiana was going to travel to Los Angeles and take two straight road games.

On June 19, 2000, the Lakers captured the NBA championship, winning 116–111 behind O’Neal’s 41 points and 12 rebounds and Bryant’s 26 points and 10 rebounds. In the fourth quarter of a tight contest, the stars teamed up for 21 points and 7 boards. When it finally ended, O’Neal—battered, exhausted, in need of a long nap—stood in the middle of the Staples Center floor, surrounded by teammates and fans, and bawled.

“I held emotion for about 11 years now,” he said. “Three years of college, eight years in the league, always wanting to win. This is what I wanted to come to the NBA for. It just came out.”

Moments later, O’Neal cradled the Larry O’Brien Trophy in his lap. He rested his shaved head against the golden ball, a man at peace with his place. He was the Finals MVP, which was wonderful and dandy.

But this was about far more than an individual accolade.

This was about legacy.