Inside the 1968 NBA All-Star-Laden Exhibition Played in Honor of Martin Luther King Jr.

It was April 5, 1968, the day after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on the Lorraine Motel balcony in Memphis, when Oscar Robertson, head of the National Basketball Players Association, picked up the phone. Game 1 of the Eastern Conference finals between Bill Russell’s Celtics and Wilt Chamberlain’s Sixers was scheduled for that night in Philadelphia. And while there were talks among players on those teams about not playing, the game went on as planned.

Still, Robertson wanted to recognize King with a tribute. Some of his contemporaries had met the minister; others attended speeches as they grew more politically active in the ’60s. So Robertson spoke with Larry Fleisher, the union’s counsel, and then started dialing the phone number of each team’s player representative to talk about what could be done to contribute to King’s cause.

One by one, players signed on to play a memorial game during the offseason. Atlanta’s Lenny Wilkens, who had met King and played a game of hearts with him while on a stopover in Birmingham between exhibition games five years earlier, wanted in. San Francisco’s Al Attles followed suit. When he was a sophomore at North Carolina A&T, he went to hear King speak at nearby Bennett College's Annie Merner Pfeiffer Chapel. The night’s lecture was “A Realistic Look at Race Relations.” King’s oration on the ballot’s importance stayed with Attles.

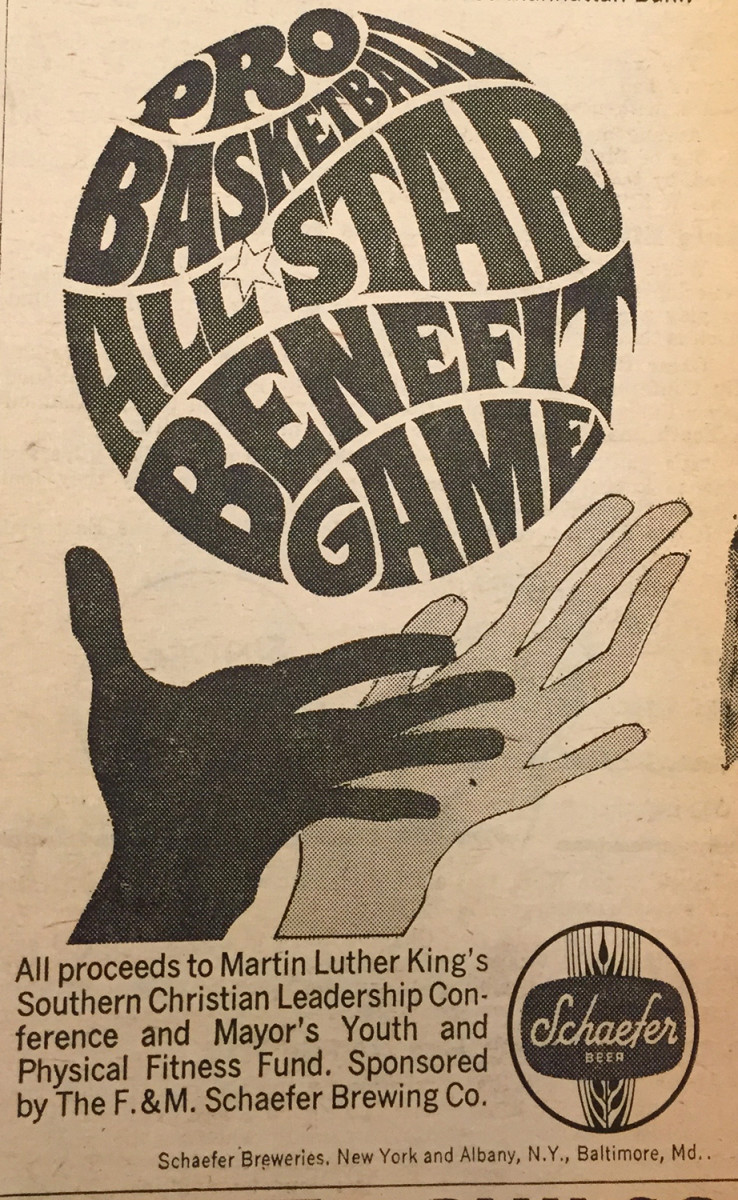

In all, Robertson recruited a constellation of 27 stars. A date was agreed upon: Aug. 15. The site would be the Singer Bowl, an outdoor, blacktopped venue on the site of the 1964 World’s Fair site in Queens. Proceeds would be split between King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and New York City Mayor John Lindsay’s Youth and Physical Fitness Fund.

In an era of summer spectacles held on urban asphalt at Rucker Park in Harlem and the Baker League in Philadelphia, players relished the competitive runs in the open air. But looking back, Earl Monroe, then a Baltimore Bullet, laughs at the idea of such an event being played today in an era of biometrics and billionaire owners’ eyeing the bottom line. “You know the NBA would not sanction that today,” he says. “They would look at it and say, ‘No, not that $100 million guy, he can’t go there!’”

In the summer of 1968, Never a Dull Moment, a Disney heist comedy, played in movie theaters across a country convulsed by violence. Nightly broadcasts brought breaking news from Vietnam into viewers’ living rooms. Unrest reigned in the streets; two months after King was killed, Senator Robert F. Kennedy was shot dead in Los Angeles. Rock and roll mixed with funeral dirges.

Center stage at the Singer Bowl was prime real estate for entertainers that summer. On Aug. 2, the Who opened for the Doors. At the end of the month, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were slated to close out the New York Rock Festival.

In between, the NBA stars would claim headliner status. It wasn’t so unusual to see the league’s best play an exhibition in August. It had become a rite of summer for players to report to the Kutsher’s Country Club in Monticello, N.Y., a Catskills Mountains town 90 miles north of Manhattan, to hold a game to raise funds for Maurice Stokes. The Cincinnati forward, who fell to the floor in a game in 1958, hit his head and was stricken with posttraumatic encephalopathy. Stokes never played another game and was cut that offseason, left with no income as hospital bills mounted. Jack Twyman, a teammate, became Stokes’s legal guardian and sought ways to defray costs. To raise funds, Twyman gathered a group of All-Stars for an annual benefit game on hotelier and basketball fanatic Mitch Kutsher’s grounds.

In 1968, the game of basketball was just starting to recognize its reach. Chamberlain was traded to Los Angeles in the offseason, supercharging the Lakers-Celtics rivalry. And the future looked bright, too: In January, the University of Houston and UCLA clashed at the Astrodome in the first NCAA regular-season game broadcast nationwide in prime time. Billed as the Game of the Century, the matchup pitted the Bruins’ Lew Alcindor, not yet Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, against Houston’s Elvin Hayes. It concluded with Houston’s upset win, 71-69, to end UCLA’s 47-game win streak.

Hayes had not yet played a game in the NBA, but he was in Queens for the King event. And still a student, Alcindor, a Manhattan native who gained prominence for his social stances in support of boxer Muhammad Ali in 1967, was back in town. Dressed in a dashiki, he drew a crowd when he arrived.

“Dr. King stood for holding America accountable for what it said it was about,” Abdul-Jabbar says. “We are supposed to be the land of the free and the home of the brave. Dr. King wanted America to be held up, accountable to that aspiration.”

Robertson and Fleisher embraced the power of television in raising funds for the benefit game. WPIX, a local television station, was on site with operators working a battery of telephones, and, instead of commercial breaks, entertainment personalities appeared on screen to collect pledges throughout the night.

As for the game itself, the teams were divided into players from the Eastern and Western conferences, just as in the NBA All-Star Game. Tipoff was 8 p.m. Tickets ranged from $2 to $5. The top two MVP vote-getters, Chamberlain and Wilkens, played together on the West team. And in the half-filled stands, 7,500 fans watched two Knicks—Willis Reed and Walt Bellamy—lead the scoring with 12 points each for the East. Just as players competed hard in the annual Stokes contest, both sides took the game seriously. Dave DeBusschere, then a Piston, suffered a severely sprained ankle. The East, captained by Robertson, beat the West, which was led by Chamberlain, 77–61. They raised $85,000 in the two-hour telethon.

For Robertson and the players, the reward was in the reception both that night and in the next day’s newspapers.

“It was the kind of show men of good will or all creeds could appreciate,” Norm Miller wrote in the New York Daily News.

The players are in their 70s and 80s now, retirees looking in the rearview at the paths they took since 1968. Dave Bing, then a Piston, was eventually elected mayor of Detroit, and the Knicks’ Bill Bradley served in the U.S. Senate. Wilkens was inducted into the Hall of Fame three times, as a player, head coach in the NBA and assistant coach of the Dream Team. In their own ways, they all answered King’s call to raise their voices amid turbulent times.

“I don’t think it was looked upon favorably at the time, but I think things have changed quite a bit,” Wilkens says of his activism in the ’60s. “A lot of people don’t even know I was in the military. After my first year of pro ball, I had to go on active duty. I believe in my country, support my country.”

He knew about the issues that led King to refer to America as a “sick” society. When he played in St. Louis as a rookie, downtown restaurants refused him service. When he moved into an otherwise white neighborhood, FOR SALE signs went up on lawns. Wilkens admired King’s willingness to test society’s status quo.

“I couldn’t believe the dedication he had,” Wilkens says, “He had a saying: Judge a person by the content of their mind and not the color of the skin. I refused to be intimidated because of people like Dr. King.”

It is a rite of winter now that the NBA honors King on the third Monday in January with a full slate of games on the federal holiday that celebrates his birth. Participants from the 1968 game play ceremonial roles these days. In 2003, Attles was part of a tribute in Memphis when the Grizzlies celebrated their second season.

A native of Washington, D.C., Bing grew up 10 minutes from the U.S. Capitol building before becoming the first Black basketball player at Syracuse and moving to Detroit to play professionally. He bore witness to the wreckage left by the 1967 Detroit riots, spurred by a police raid of a Black speakeasy. In 1968, he was back home in D.C. with his two children when King was assassinated. Riots roiled his hometown.

King’s call for nonviolent protest always stayed with Bing. And he was troubled by the insurrection at the Capitol perpetrated by pro–Donald Trump extremists on Jan. 6.

“It takes me back to when our country was going through hell because that’s where we were and that’s where we are today,” he says. “You would think we would have learned, but we haven’t. As great a country as America is, we have so many problems that need attention. This is all a reminder of how far we have to go.”