Meet Mr. Net

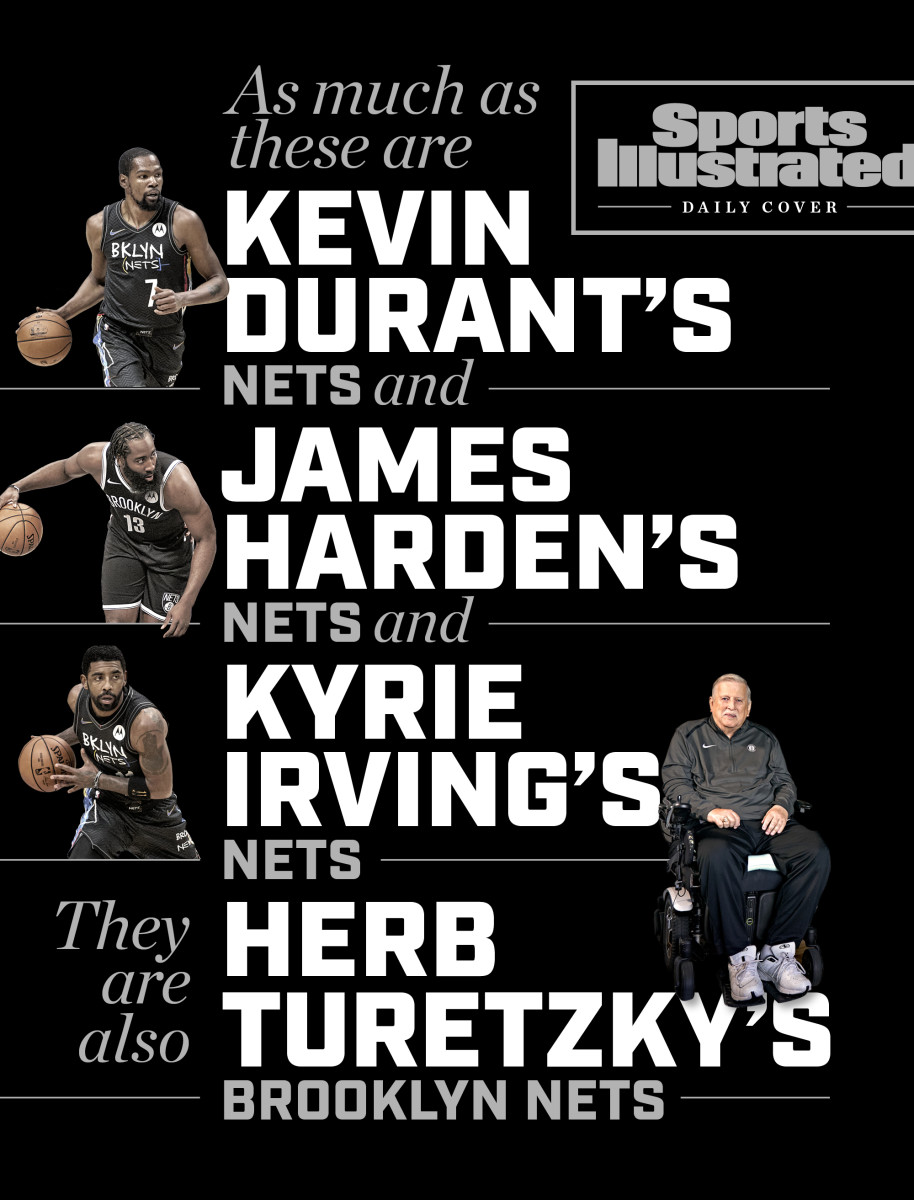

As Herb Turetzky and his wife, Jane, pulled into the parking area at Barclays Center just over two hours before the Nets’ preseason opener in December, the 75-year-old felt a jolt of energy pulse through him. Nine months had passed since Turetzky had been in the arena, marking the longest stretch in more than 50 years that he had gone without sitting courtside at a basketball game.

Since the first day that the Nets franchise—initially known as the New Jersey Americans—took the floor in 1967, Turetzky has been watching from his station at half court. As the team’s official scorer, he has worked more than 2,200 games, a Guinness Book of World Record for professional basketball, including at one point scoring 1,465 consecutive contests. But after 54 years of service, Turetzky is more than just a tallier of statistics. Those who have come to know him describe him as a historian, an encyclopedia, a shrink and a close friend.

“It’s not a Nets season without Herb Turetzky,” says long-time team broadcaster Ian Eagle. “It’s that simple.”

“He’s a treasure,” adds former Nets great and Hall of Famer Julius Erving. “He’s part of the original franchise. Who else has that?”

There has never been an NBA season quite like the one Turetzky is in the midst of now. In recent years, he and his wife have grown accustomed to schmoozing in the Barclays Center press room before home games, where they often enjoy a pregame meal. However, revised policies caused by the coronavirus pandemic meant that he enjoyed half a leftover pastrami sandwich in the front seat of the couple’s white 2017 Dodge Caravan instead ahead of the Nets-Wizards exhibition on Dec. 13. As his wife helped him into his courtside seat more than 90 minutes before tipoff—Turetzky has used a wheelchair in recent years and has spastic paraparesis, a disorder that causes gradual weakness in the legs—he couldn’t help but notice all the other stark differences.

For starters, he had a blue cloth mask draped over his mouth and tucked under his glasses. Olivier Sedra, Brooklyn’s public announcer who normally sits shoulder-to-shoulder with Turetzky, was more than six feet to the scorer’s right. A group of statisticians who in most years are stationed within earshot behind him had been moved to the upper bowl, forcing Turetzky to wear a black headset over his thinning white hair to ease their communication. There were no fans or vendors in the seats behind Turetzky, who grew up just eight subway stops from Barclays in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn. “Honestly, it’s kinda lonely,” he says. “It was very, very strange.”

Still, a few visitors did greet the man that longtime NBA official Bob Delaney calls “the Michael Jordan of scorekeepers.” Wizards assistant coach Robert Pack, whom Turetzky refers to as “forever 22” in honor of a 22-assist game Pack recorded while playing for the Nets in 1996, said hello during pregame warm-ups. So did David Adkins, another Washington assistant. Brooklyn’s Spencer Dinwiddie came over and was thrilled to hear that Turetzky’s six-year-old grandson was practicing his crossover dribble by watching the guard’s highlights. Nets assistant head coach Jacque Vaughn also stopped by, and the two briefly chatted at a safe distance. In the seconds just before tipoff, two more visitors acknowledged Turetzky: Nets stars Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving. Each exchanged a fist-bump with the franchise’s elder statesman.

“We’re gonna have a chance if things go well for those guys and they all stay healthy,” Turetzky says. “Being at the top is special. But being at the top in Brooklyn would be so much more special.”

Turetzky attended the New Jersey Americans’ first-ever game in October 1967 expecting to watch purely as a spectator. He was looking forward to seeing New Jersey star, and fellow Brownsville native, Tony Jackson battle Pittsburgh Pipers forward Connie Hawkins, who was also born in Brooklyn. The night of the game, Turetzky, then a college student at Long Island University Brooklyn, arrived early at the Teaneck Armory in his red 1964 Plymouth Fury. Max Zaslofsky, the Americans’ coach and general manager who was also from Turetzky’s neighborhood, greeted him as he walked in. “Herb, can you help us out and keep score of the game tonight?” the Americans’ coach asked. “Max, I’d love to,” he responded. “I’m here, so why not?”

Turetzky sat down at a wooden folding chair at half court and started jotting down the game’s lineups. “I’ve never left that seat since,” he says. “I’m still here and I’m still going.”

Turetzky first grew fond of basketball as a teenager at the Brownsville Boys Club, a recreation center that became a hub for the neighborhood’s Jewish immigrant children. He’d spend countless afternoons there practicing his ballhandling and jump-shooting. It was at the Boys Club that Turetzky also learned the administrative elements of the sport, like how to operate a scoreboard and how to keep a scorebook. “Be sure to look at each team as if they were equals,” he remembers being told. The advice has stuck with him throughout his career.

Delaney, the longtime official, first met the Nets stalwart in 1985, and the two created a strong professional relationship over the course of Delaney’s two-plus decade career. The official describes an NBA game as a contest involving four teams: the two competing, the referee team and the scorer’s table. “How they are able to operate and if they’re in concert, it makes our jobs as referees so much easier, because that’s the administration of the game,” Delaney says of the scorer’s table. “They’re keeping the fouls. They’re keeping the shot clocks. And Herb is like the captain of that team.”

Consistency has been integral to Turetzky’s success. In a normal season, he arrives around two hours before every home game so he can relax for a pregame meal. Decades ago, he roamed the hallways of the various arenas to flag down visiting coaches and get their lineups, but the last coaches he remembers chasing down were Phil Jackson and Don Nelson through the underbelly of Meadowlands in the early 1990s. Nowadays, after getting settled at half court around 90 minutes before tipoff, he is given the game’s actives and inactives before being briefed on the starting lineups. “What else is constant is that nobody’s ever had one bad thing to say about him,” says Jayson Williams, a Nets forward from 1992 to ’99.

For every game, Turetzky writes the starters in a specific order, from top down: small forward, power forward, center, shooting guard and point guard. And later he gives a number of last-minute fist-bumps to whichever players seek him out. Vince Carter, he says, was “the best pregame fist-bumper I ever had.”

Night after night, Turetzky is the game’s constant. In a preseason contest in 1972, New York Nets center Jim Chones dove into the first row of the stands, colliding with Jane, knocking her out. The Nets’ official didn’t leave his seat following the play, but instead watched from his station while a team doctor, Alan Levy, went over to assist.

In 1993, when Shaquille O’Neal was a rookie on the Magic, Turetzky watched in an April game as the bruising center smashed a backboard with a ferocious dunk. Turetzky’s son, David, was a New Jersey ball boy at the time and was sitting right under the rim. Jane sprinted down to the floor thinking her son’s foot had been crushed. But again Turetzky stayed put. “Stay away from falling baskets,” O’Neal told David ahead of the teams’ matchup the following season.

“[His calm is there] if there’s two seconds in a game and you go over and ask him a question or if you go over at the 10-minute mark.” Delaney says. “You’re getting the same kind of approach.”

Throughout gameplay, Turetzky keeps his head on a swivel, always aware of where the ball is. Using a Nets souvenir ballpoint pen, he records the field goals made; the free throws made and missed; and the personal and technical fouls. He keeps a log of timeouts and a running summary of the score. A group of statisticians also keeps a record of the game’s action, but when trainers, assistant coaches and referees have questions about a contest’s administration, they approach half court and find Turetzky’s familiar face. “It puts you at ease as a referee knowing that everything’s been handled,” Delaney says.

Not much has changed in the world of scorekeeping since Turetzky’s first game with the franchise, though with the advent of replay reviews and coaches challenges, he’s been forced to write over his work more than ever before. “My ego doesn’t get involved,” he says. One thing he no longer has to do, however, is phone in his box scores to the Elias Sports Bureau. It was a practice that his son, David, and his daughter, Jennifer, used to mimic when they were children and one that has been rendered obsolete because of modern technology.

“I’m the last dinosaur in the building,” Turetzky says. “I’m still using pen and paper. Everything else is done on a computer.”

In the waning seconds of the 1976 ABA finals, Dr. J heaved a full-court baseball pass to a wide-open John Williamson, who was streaking up-court fully unguarded. Holding a four-point lead over the Nuggets, Super John retrieved the outlet pass and started dribbling out the clock to the delight of the 15,000-plus fans at the Nassau Coliseum. Turetzky, wearing his bright-red scorer’s blazer with a Nets logo stitched onto the left breast pocket, watched as the fans in the lower bowl prepared to rush the floor. When the final buzzer sounded, Turetzky took in the excitement of the lone court-storming in franchise history and put the finishing touches on the night’s score sheet, the last-ever in the ABA.

As Turetzky walked back toward New York’s locker room, Nets point guard Brian Taylor found the scorekeeper and ushered him into the team’s celebration. “Herb was always there for us,” Taylor says. “He was more than just the official scorekeeper. He was like our shrink.” At one point amid the jubilation, Taylor grabbed Turetzky and pulled him into the Nets’ shower, where Turetzky, still wearing his blazer and holding his attaché, was thoroughly doused in champagne. It was there that he saw Erving, reclining against a bathroom wall. “I’m just trying to relax and understand what we just did,” the Doctor told him.

Turetzky and the franchise have not experienced that euphoria since.

The Nets joined the NBA ahead of the following season, but sold Erving to the 76ers for $3 million following a contract dispute, a decision that still haunts the franchise decades later. By the end of the 1970s, the team played at Rutgers in Piscataway, New Jersey, where Turetzky recalls one night when spectators were given Frisbees as part of a promotion, only to have fans throw them onto the floor during a frustrating fourth quarter call. In 1981, the team moved to the Meadowlands sports complex in East Rutherford, yet another jump for the nomadic franchise.

During almost all of his first two decades with the team, Turetzky spent his days as an elementary school teacher in Brownsville. But by the mid-’80s, he stopped teaching and opened a trophy business in Queens. Still, working Nets games at nights was a priority.

Beginning in 1984, Turetzky was present at every Nets home regular-season and playoff game—1,465 in all. The streak was snapped after a viral infection forced Turetzky, who left the trophy business in 2010, to be hospitalized ahead of the Oct. 28, 2018, game against the Warriors. “It hurt,” he says, not of the medical ailment, but of watching the Nets play a home game without him in attendance. “It hurt very badly.” And he hasn’t missed a home game since.

“He’s the official scorekeeper extraordinaire,” Erving says. “A lot of people could be scorekeepers. A lot of people could be official. But not everybody could be an extraordinaire.”

In an 11-by-14-foot room in Turetzky’s penthouse floor apartment in Queens, which overlooks the Throgs Neck Bridge, is a memorabilia collection that encapsulates the history of the Nets franchise. There is a photograph signed by all the members of the original New Jersey Americans team and autographed scorebooks that hold game logs for every Nets home game during their ABA title runs. The vibrant red scorer’s blazer that Turetzky wore in the shower with Erving is prominently displayed. He has three tickets that would have been for Game 7 of the 1976 finals against the Nuggets had New York not closed out the series in six, autographed by Erving, Denver star David Thompson and both of the series’ coaches.

There are signed jerseys and sneakers, and various other knickknacks scattered about, including a Jason Kidd matryoshka doll and a copy of the hit 1994 film Above the Rim, in which Turetzky appears as an extra. On an early December afternoon, Turetzky even apologizes for the absence of six objects, including a net used in the first game at Barclays Center, which are currently on loan for an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York. “I don’t think the Basketball Hall of Fame has anything on Herb’s collection,” says Muarice Williamson, son of the late Nets star John Williamson.

“It’s Nets history,” Jane adds. “But it’s our family history as well. It’s our lives.”

Turetzky’s loyalty to the Nets isn’t reflected only in his memorabilia collection. In recent years he has also organized unofficial reunions for dozens of players from the team’s past. “He’s really been my only contact with the team since I played,” says Dan Anderson, who scored 41 points in the first game in the franchise’s history.

Eagle, who became the Nets’ play-by-play man in 1994, says that Turetzky is “the go-to” for any questions about the organization’s past. “It’s rare that you can say [someone] has literally seen it all in the team’s history,” he says. “Forget about googling it. You can get a live human being that has not just the knowledge, but first-hand knowledge of what happened, when it happened and who was involved.”

On March 6 of last year, Erving attended his first Nets game at Barclays Center since the team moved into the arena in 2012. Before the game, he ran into Turetzky in a hallway, where the two shared a warm embrace and a little teasing. “It was memorable in that it took me back to the Nassau Coliseum,” Erving says. “Because there’s so many times we’ve been in each other’s presence.”

Two nights later, Turetzky found his seat at half court like he had done more than 2,000 times before. Using his black Nets pen he wrote down the game’s starting lineups and later tallied the statistics in a mundane 110–107 Brooklyn win over the Bulls. After the final buzzer sounded, Turetzky clipped three pens to the top of his scorebook, bookmarking his place. He put the scorebook in his black attaché, not knowing that the next time he would look at it would be December.

Much would happen in the ensuing months. Turetzky was hospitalized for four days in April after contracting COVID-19, an experience that he described as “scary as hell.” While he eventually recovered, he watched the Nets’ postseason bubble run from his apartment, marking the first time he hadn’t worked a full playoff run in the franchise’s history.

For the 2020–21 season, Turetzky and his wife have to appear at Barclays Center on two of the three days before home games for coronavirus testing, as both are among the few nonplayers permitted to be in the stadium’s lower bowl. Despite the extra driving and additional precautions, Turetzky has no plan to slow down. “We never talk about it,” Jane says. “I told him a few years back, stop trying to put an end to something. You’ll know when it’s right. It will just hit you.”

As he had done in his prior 53 seasons, Turetzky started a new scorebook this past December. The players are vastly different from his first season and so too is the style of play he now witnesses on a nightly basis. Still, “he keeps finding joy in doing this job,” says Eagle. “And if something makes you happy, you don’t mess with it.”