NBA Skills Coach Irv Roland Turns Attention Toward Activism

Irv Roland admits: This wasn’t the plan.

“Not at all,” Roland said.

Coaching—that was the plan. Roland cracked the NBA in 2004, as a video assistant in Boston, beginning a journey that took him through New Orleans, Phoenix and Houston. He opened a business, Blueprint Basketball, and became a trusted trainer for Kevin Durant, Kyrie Irving and Trae Young, among others. In Houston, ESPN referred to Roland as James Harden’s secret weapon.

In 2019 the plan changed. Roland was let go by the Rockets, part of the purge of Mike D’Antoni’s staff. He moved to Los Angeles and spent the next year working out players, looking for other NBA options. Last March when the pandemic hit, Roland, 39, moved back to Houston. He lived out of a hotel and worked with Rockets players, keeping them sharp while the NBA evaluated its options.

Last May, George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police officers. The video of Derek Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck quickly went viral. In Houston, where Floyd grew up, the images were especially painful.

For Roland, too. Activism has always been strong for Roland, an Oklahoma native. He publicly supported Colin Kaepernick. He counts Huey P. Newton, the founder of the Black Panther Party, among his idols. But more than a decade spent regularly crisscrossing the country limited his involvement. When Floyd died, Roland went to a rally in Houston put together by a friend, rapper Trae tha Truth. He marched, alongside tens of thousands of others, to protest Floyd’s killing.

The rally, Roland says, “activated” something.

“When George Floyd happened, I jumped on the bandwagon,” Roland told Sports Illustrated. “This is something that I've always been about, but because I was working for teams or players in general, I didn't have the time to be present like I do now because I work on my own.”

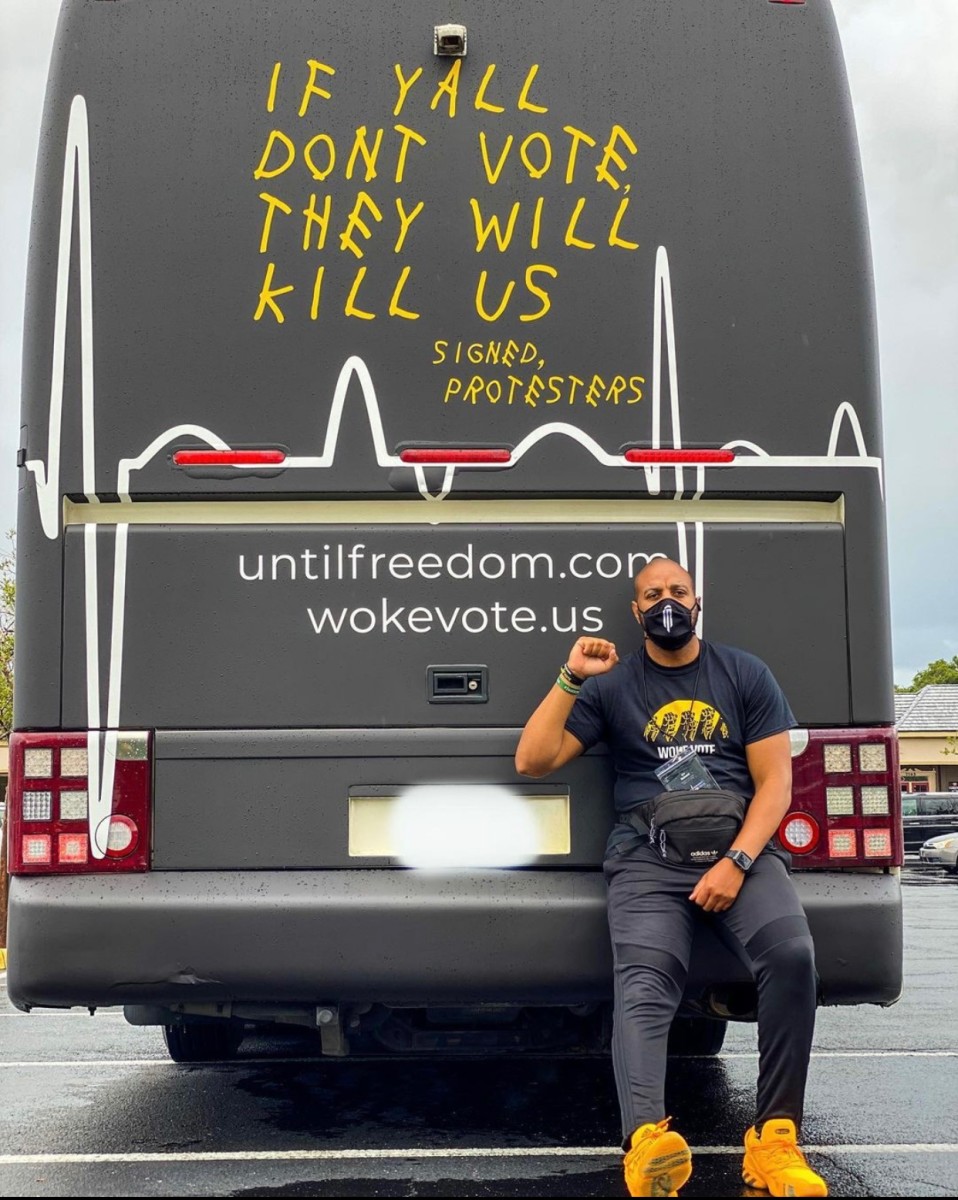

The Floyd march triggered something in Roland. In July Roland was in Louisville, camped out on the lawn of Daniel Cameron, the Kentucky district attorney assigned to the investigation of the death of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old EMT shot and killed by Louisville police. Roland was one of 87 arrested, zip-tied, booked and jailed for the peaceful protest. Last fall Roland was back in Oklahoma City, protesting the police shooting of 15-year-old Stavian Rodriguez, who held up a convenience store.

Roland has become a magnet for people looking to raise awareness of an injustice. Messages fill his inbox on social media from people looking for his help—as well as the muscle some of Roland’s high-profile friends can provide. “I always have to be educated,” says Roland. “Because I don’t want to just be almost like the boy that cried wolf and I’m just out here showing up for everything, when in fact, the cops weren’t in the wrong. So I just always try to educate myself as much as possible on these issues.”

Roland’s athlete friends have been supportive. Kenny Stills, an NFL wide receiver, was among those arrested with Roland in Kentucky. Young has been involved. George Hill, too. Irving has been supportive. Yet at times Roland can’t help but think many athletes could be doing more. Last summer Roland made six trips to Kentucky to continue to raise awareness for Taylor’s death. He worked at a food drive, partnering with Taylor’s family, that fed more than 2,000 people. He reached out to dozens of NBA players. Two—Josh Okogie and Jarred Vanderbilt—showed up.

“One thing that I’ve learned, and I've tried not to get upset about it, is the fact that for a lot of these guys, some of it is performative,” says Roland. “You see one player post about something and you feel like, all right, cool, let me post Black Lives Matter. So people don’t feel like I’m a sellout or something like that. When in actuality, they don’t really care that much about these issues. Because a lot of them are too far removed. And I say that without trying to bash anybody—it’s just the fact of the matter.

“What I would challenge players, celebrities, whatever to do is get connected with local organizations, wherever you’re from—whether it’s your hometown, where you grew up, the city you play in, whatever—get connected to these people and start to back them and push them where they need to go. And the next thing you know, whatever ideas they have to get presented, boom. Rather than you trying to start from scratch and get stuff done on your own, because it’s not really going to work because most of these guys aren't really going home every night and thinking through these issues.”

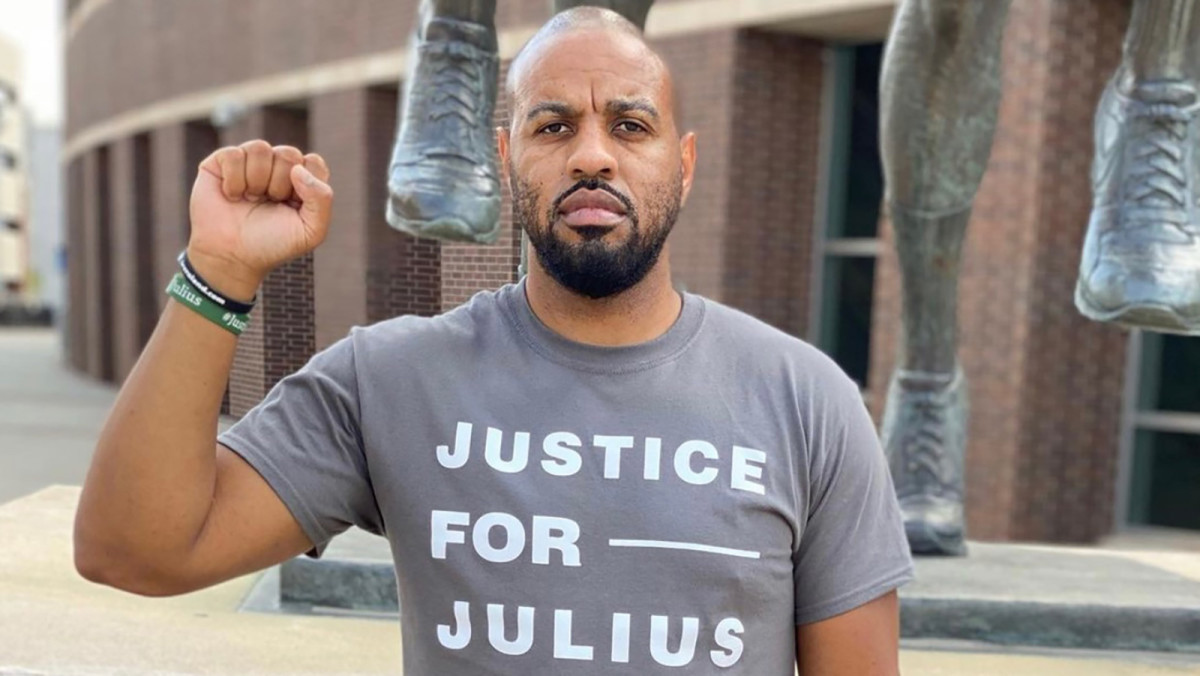

Roland continues to train players. And he is hopeful for an NBA return. Activism, though, will remain a part of his life. Last month Roland was back in Oklahoma. In 1999 Julius Jones, a close friend of Roland’s, was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. In recent years the case has come under intense scrutiny, with allegations of impropriety by law enforcement and racial discrimination. Kim Kardashian has taken an interest. Viola Davis created a docuseries. Along with four friends, Roland marched from the state capitol in Oklahoma City to McAlester, home of the state penitentiary.

“My career is basketball; that’s how I make my money, that’s how I built up the smaller platform that I have is through coaching in the NBA for 15 years,” says Roland. “And I still love it. I work with a ton of NBA players. I work with a ton of kids. I still love basketball, but I feel like my calling is being front and center for these issues, because this is what I’m passionate about. There are a bunch of basketball trainers and I feel I’m decent at what I do, but there are a ton of guys that do what I do. But I think being present for these issues is something that God has led me to do. This is all about, how can I help create a difference on whatever the issue is. And also maybe I can motivate somebody who has a bigger platform or following than me to come join the fight.”