‘We Have a Lot More to Do’: Inside the NBA’s Unprecedented Social Justice Coalition

The National Basketball Social Justice Coalition’s seeds were planted Aug. 26, 2020, three days after Jacob Blake was shot in the back seven times by a white police officer in Kenosha, Wis. About 1,200 miles away in Disney World, NBA players were frustrated over the police shooting of another Black man—one that came exactly 90 days after George Floyd was murdered by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

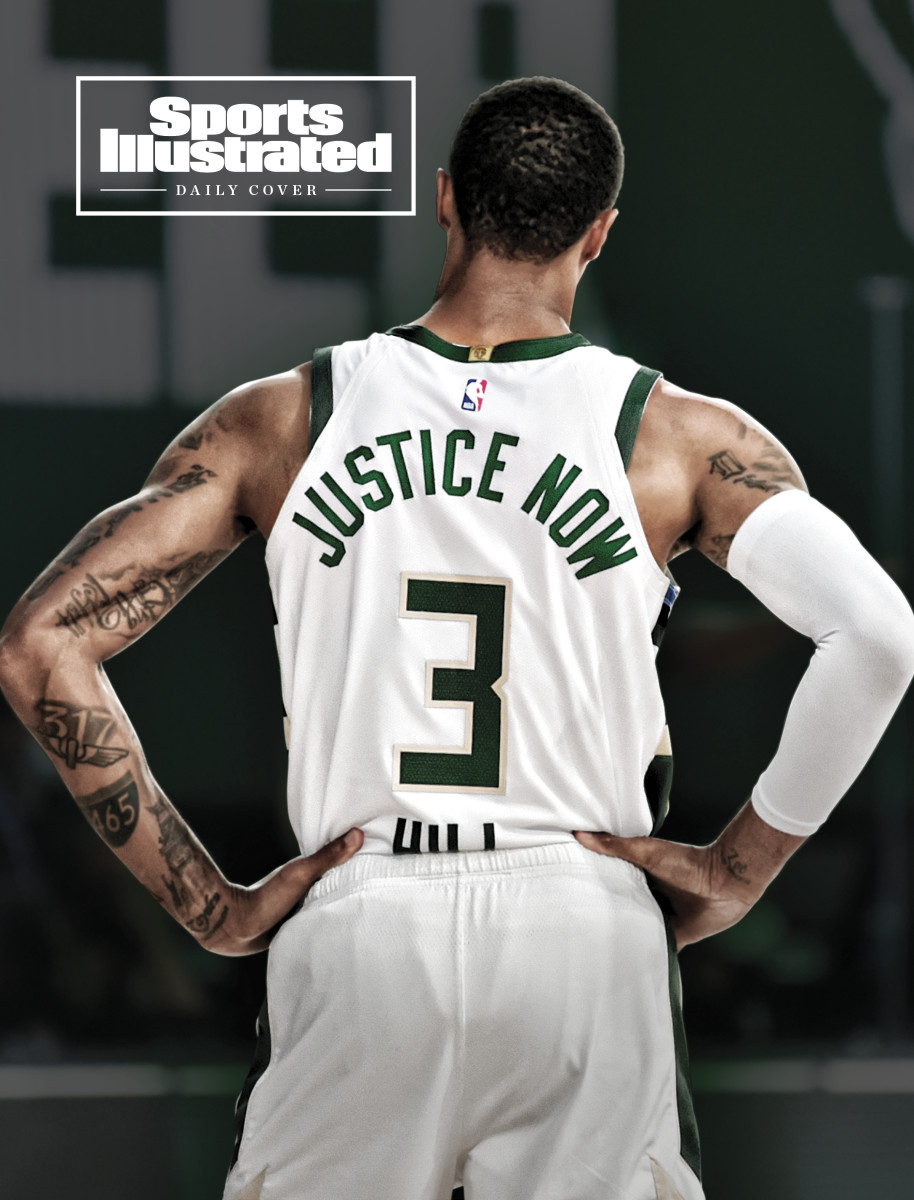

Action first came when the Bucks, led by George Hill and Sterling Brown, refused to play Game 5 of their first-round series against the Magic. Their decision precipitated a league-wide shutdown and, that very night in a hotel ballroom, a tense meeting where players hashed out whether the season should continue. The issue was urgent, but wrapped inside a far more meaningful question: How could long-term change be wrested from such a historic moment?

“They wanted something that would last longer than them,” says Sixers coach Doc Rivers, who was a vocal presence in the room that night.

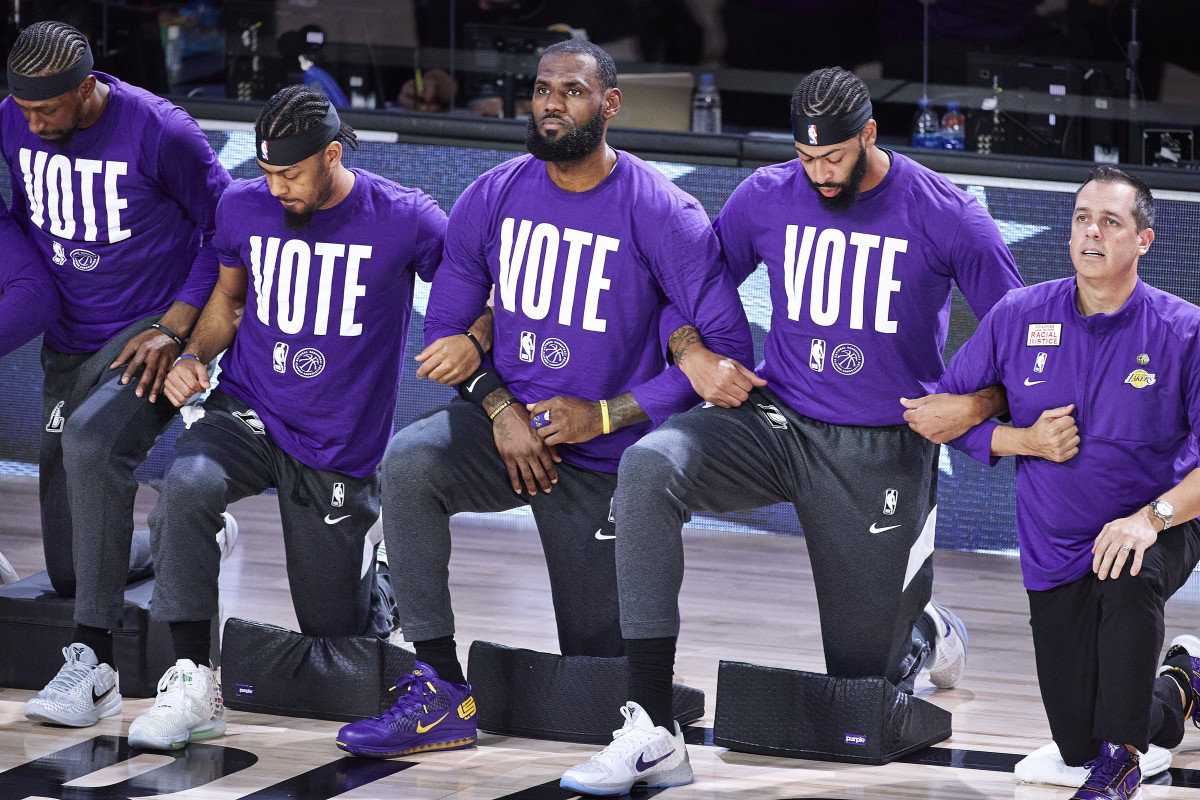

An emotional night of debate and information gathering (including a phone call between LeBron James, Chris Paul and Barack Obama) stretched into the early morning, when players held a virtual meeting with NBA owners to outline several ways they could directly impact racial inequality beyond drawing awareness to it through the sudden interruption of their own labor. With playoff games on hold and hundreds of millions of dollars on the line, the league and its owners were compelled to shape an alliance.

“I will not be cynical and say it was because of the games to resume,” NBPA executive director Michele Roberts says. “But it helped that there was some leverage in being able to continue playing.”

On Nov. 20, 2020, the coalition and its 15-person board—five players (Brown, Carmelo Anthony, Avery Bradley, Karl-Anthony Towns and Donovan Mitchell), five governors (Clay Bennett, Steve Ballmer, Marc Lasry, Vivek Ranadivé and Micky Arison), two coaches (Rivers and Lloyd Pierce, who was later removed after the Atlanta Hawks fired him), NBA commissioner Adam Silver, NBA deputy commissioner Mark Tatum and Roberts—were formally announced. (In December, Pistons coach Dwane Casey became the coalition’s newest member.) It’s potentially the most powerful upshot from the players’ decision to strike. In size, scope and aspiration coming from a professional sports league, it’s an effort that has virtually no precedent.

Instead of chipping in with traditional philanthropy—which is what the newly formed NBA Foundation does—the coalition aims to affect public policy throughout the country. As the coalition’s executive director James Cadogan says, “Most organizations of the size and heft to the NBA are doing their advocacy on corporate interests. We’re doing our lobbying, in this case, from a purely values-based perspective.”

The coalition wants to draw awareness toward bills that defang racist systems, then attract potential voters invested in those same causes to sway elections. At the same time, they hope to directly influence legislation by engaging elected officials behind the scenes, letting them know what the NBA, as a collective, thinks. “What’s exciting about this, to me, is we’re building a traditional advocacy organization in a very nontraditional way,” Cadogan says.

But couched into its singularity is a healthy skepticism from longtime racial justice advocates, politicians and onlookers wary of what happens when a brand as large as the NBA seeks to enter a fight as hostile as the one for racial equality.

What can this body realistically accomplish? How should its effectiveness be judged? And, when tackling highly consequential and contentious issues its own board members might not agree on, how progressive can a coalition this inclusive truly be? It’s only been a little over one year since it officially joined a battle that’s centuries old—Cadogan is still in the process of building a full-time staff, with at least four positions still needing to be filled—but these questions are baked into the task at hand.

Eventually, results will matter.

The coalition’s first major internal decision was hiring an executive director to oversee day-to-day operations. Hundreds of candidates applied for the job and a subcommittee was created to sort through resumes and conduct interviews. Cadogan, who was a senior official in the Obama administration’s Department of Justice and the first director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s Thurgood Marshall Institute, emerged from a group of five or six finalists.

After he was hired in April, Cadogan met with his Board members to hone in on three issues—police reform, criminal justice and voter suppression. This led to the Coalition supporting three bills over the past eight months: The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the EQUAL Act. All three have passed in the House. None have gotten through the Senate to become a federal law. The setbacks are exhausting.

Four months after the George Floyd bill was approved in the House, Republican Senator Tim Scott, of South Carolina, and Democrat Representative Karen Bass, of California, participated in a roundtable discussion with Towns and Ballmer that was put on by the coalition. The interaction held a kernel of optimism. But then in September, Senate negotiations broke down when Scott accused Democrats of wanting to defund the police, a tone-setting body blow that encapsulates how thorny the coalition’s course can be.

“Disappointment is going to be part of this game, for sure,” Rivers says. “[It’s] something that probably a lot of us aren’t used to, but we will now that we’ve gotten into the political arena. We’re in the business of democracy right now.”

Says Lasry: “You can try to convince people you’re right; you can make the argument as to why they should support something. Or you can try to elect people who already share that view. … And we’ll keep trying, either by being able to convince people, or by having different people who are in those seats who share our opinion.”

The coalition has no choice but to forge relationships and pitch as many open-minded lawmakers currently in power as it can. (Lasry, whose son Alex is running for a Senate seat that’s held by Wisconsin Republican Ron Johnson, says he has introduced elected officials to Cadogan, but declined to name them.)

“We’re gonna make the NBA community heard in the halls of power,” Cadogan says. “And they’re paying attention.”

Representative Kelly Armstrong, a Republican from North Dakota, is one example. In July, Armstrong sat in a meeting with members of the coalition to discuss the EQUAL Act, a bill he co-sponsored that will eliminate the federal sentencing disparity between drug offenses involving crack cocaine and those involving powder cocaine. A criminal defense attorney before he was elected, Armstrong dealt with many organizations that feigned interest in criminal justice reform to generate good PR. He was initially unsure about the coalition, but during the Zoom call he brought up the challenges of community reentry for incarcerated people, a topic he anticipated them not considering beforehand, and something Armstrong believed the NBA could get involved in. The conversation shifted and coalition members began peppering him with follow-up questions.

“It was really cool that they engaged on something that wasn’t just on their talking points before they started the meeting,” Armstrong says. He left that first meeting believing in their commitment.

Armstrong acknowledges the NBA’s mass appeal, citing his 12-year-old son who could not care less what a U.S. House member has to say, but, as a huge Bucks fan, listens when his favorite players speak. He isn’t the only politician who feels this way.

Bass, a Democrat from California, is thrilled the coalition exists, even if her meetings with them have been less for the purpose of lobbying and more to gather information and discuss the power of their platform.

“They’re reaching broader America,” she says. “They can help change the consciousness and awareness of people. And that is just, I mean, I just can’t stress enough how vital of a role that is and how significant it is for them to be involved.”

But a little over one year in, the coalition’s impact on the political process is faint, thanks to so much initial focus on national bills that have been stuck in the Senate. That reality has led several coalition board members, political figures and outside advocates interviewed for this story to believe a deeper focus on passing state and local laws, i.e., those that don’t require Congress’s approval, should be a larger priority.

Glenn Harris is the president of Race Forward, an organization for racial justice, and has spent 30 years fighting to dismantle racist systems from positions in and outside of government. He was encouraged to see the NBA—as an institution, along with individual players—take a stand against racial oppression in the ways they have. He’s also adamant about their need to invest at the community level as much as they already have on a national scale.

“Change happens locally, not federally. Never has. The civil rights movement? We think about it as this national reality. It was a movement in Birmingham,” he says. “And in that way, everything that we’re talking about in terms of the kind of policy changes that we’re asking for at the federal level, they all started locally, every single one of them is local. And so while federal policy change is essential, it is far from sufficient for creating change.”

While the John Lewis Act—which would restore elements of the Voting Rights Act that have been weakened by the Supreme Court—is unlikely to pass in the Senate, there are other ways the Coalition can help one of their core issues. Right now in 20 states there are still more than 245 bills that seek to restrict voting access in some way (via stricter voter ID laws, constraints on mail voting, prohibiting the use of ballot drop boxes, etc.), according to Voting Rights Lab.

Put another way by Roberts: “Congress is predictably impotent. We’ve gotta do something. That was the frustration that the players articulated in the bubble all those months ago, that we need to see concrete evidence of what we can do.”

For just about every organization that exists to achieve racial equality, success is hard to evaluate beyond the passage and implementation of laws that will directly alter the living experience of non-white people across the country. The reality is that it takes time.

“We haven’t done much yet,” Roberts says. “I think we will. But we haven’t yet.”

Even arriving at a strategic consensus within the board won’t always be easy. The coalition’s members come from dramatically different backgrounds and range from 25 to 72 years old. They include Arison and Bennett who, since 2015, have made either all or more than 75% of their political donations to Republican causes. (Through a team representative, both declined an interview for this story.)

Cadogan cited the confidentiality of board meeting discussions (there have been three since he was hired, the most recent being Dec. 9) when asked about specific conversations that take place among the group, and how much of a challenge it’s been to herd such a dissimilar, strong-minded group in one direction. But he did say: “If you’ve ever been part of a family, a team or a close-knit organization, where you have to make a group decision, then you understand the dynamics. You understand that you're going to have to go through some tough conversations in order to chart a path forward.”

Beyond the coalition’s current policing, voting rights, criminal justice triad lie several other topics that board members and advocacy operatives would like to see them get involved with. Mitchell, for example, cares deeply about education.

“I look at it as helping grow the future, because at the end of the day it’s what we’re teaching our kids, what we’re teaching our youth,” he says. “Understanding how to celebrate each other’s culture, how to celebrate one another as opposed to continuously looking at others as different and others as less-than.” The issue is urgent to Mitchell, but has not yet become a priority for the coalition.

In the future, the coalition may consider supporting local legislation, like Minneapolis’s Question 2, a momentous measure launched in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder. It would have replaced (not defunded) the city’s police department with a new Department of Public Safety. It was on the ballot last November but lost by about 18,000 votes.

“If the NBA were to lean in on not the need for police reform, but the need for reimagining public safety, I think it would be invaluable,” Harris says.

Cadogan says he was aware of Question 2 and interested to see how it shifts policing’s Overton window, but the coalition opted not to support it.

“We’re really thinking about our targets now,” Cadogan says. “As we build and as we think about, where do we do this work? Where is most valuable? Where do we get the most bang for our buck? … That’s just an ongoing set of conversations that we're gonna hone in on for 2022.”

That decision not to jump into such a divisive measure indirectly reflects how diversified advocacy-related strategy can be.

“I think the word ‘defund’ police is a bad word. I think every police would want to be a better policeman or policewoman and do the job better and [be] more efficient,” Rivers said when asked what type of legislation he’s most passionate about. “I liken it to a player who is pretty good. He still goes to practice. He’s still coached to get better.”

It’s also worth asking if high-profile NBA figures caught in racially related controversies can hamper the coalition’s credibility, especially when partnering with certain elected officials. Suns owner Robert Sarver has been under investigation by the NBA since early November, when an ESPN report alleged his consistent use of racist language over a 17-year period. Several board members did not think it would distract from their mission. They also wanted to wait for the NBA to conclude its investigation before commenting further.

“At the end of the day, we know that if we do our work systemically, and we are successful in moving an agenda on justice, that is more likely to create conditions where misconduct is less likely to happen,” Cadogan says. “Individual sets of allegations don’t have a bearing on our justice agenda.”

“Obviously I can’t speak to the Suns or the Sarver situation. That’s for Adam Silver,” Ranadivé says. “But my own experience has been that the owners are incredibly committed to these issues. And I personally have not seen a situation where I don’t see great passion and commitment for these issues. So to me there’s no issue there.”

Bass doesn’t believe it makes any sense to turn down a helping hand, especially when offered by popular players who shine light on injustice. “I know that there’s racist owners and obviously they should be kicked out of the NBA, in my opinion,” she says. “But that does not color the NBA to me.”

How all this impacts the coalition’s actual long-term efficacy matters, though. It also raises the question of how enlightened the coalition will ultimately be on topics that are rife with strong opinions and frequent disagreement. For a professional sports league serious about getting involved in an official capacity, how much engagement is enough, and what should qualify as a reasonable expectation?

“I think the skepticism is healthy. But I also think that the truth is never imagine for a moment that a sports league [is] going to bring us justice,” Harris says. “I think that their voice and their weight can help, but they are not going to bring us the country we deserve. That is going to come from our communities. And I think holding that allows me to balance out my skepticism.”

Going forward, the coalition will ask itself questions that help assess its own productivity. Did it move bills forward? Did it help get them introduced, reshaped or passed? Did it raise awareness about critical issues and make a convincing case to those who will listen that they’re something worth caring about? “Did we use our bully pulpit to its highest and best effect?” Cadogan asks.

Beyond that, the coalition will also use internal metrics that detail how many people are talking about, commenting on and engaging with the issues they’re pushing. Progress can be agonizing, though, and in the context of a struggle that feels neverending, with countless barriers propped up to make wins more elusive than they should have to be, patience is a hard pill to swallow.

“I would say that in my mind [success] can’t be tied to any individual policy win,” Harris says. “If that’s how we’re looking at measurement, there’s so much that goes into the making of sausage that it would be grossly unfair. It has to be a little more longitudinal. It’s gotta be a little bit more about how consistent have folks been in advocating for an idea and how many wins have they had. I think that matters. But also how much impact—and this one's a little more tricky to measure—have they had in moving the political debate.”

The coalition has already been frustrated in myriad ways. Their footprint won’t be known for quite some time and it’s hard to say where they go from here, knowing so much of what they do hinges on variables outside their control. But as a persistent group that was formed in a unique moment, the coalition’s very existence signals a potential sea change.

“In five years I think we’ll look back and be like, ‘Man, we’ve done some good work,’” Mitchell says. “But we have a lot more to do.”

• ‘He’s Made The Difference’: LaMelo Ball Has Charlotte Buzzing Again

• Scoot Henderson Is A Top Prospect In The G League. And He’s The Future.

• NBA's Replacement Players Are Proving They Belong

• The Warriors' Quest to Achieve What Other Dynasties Couldn't