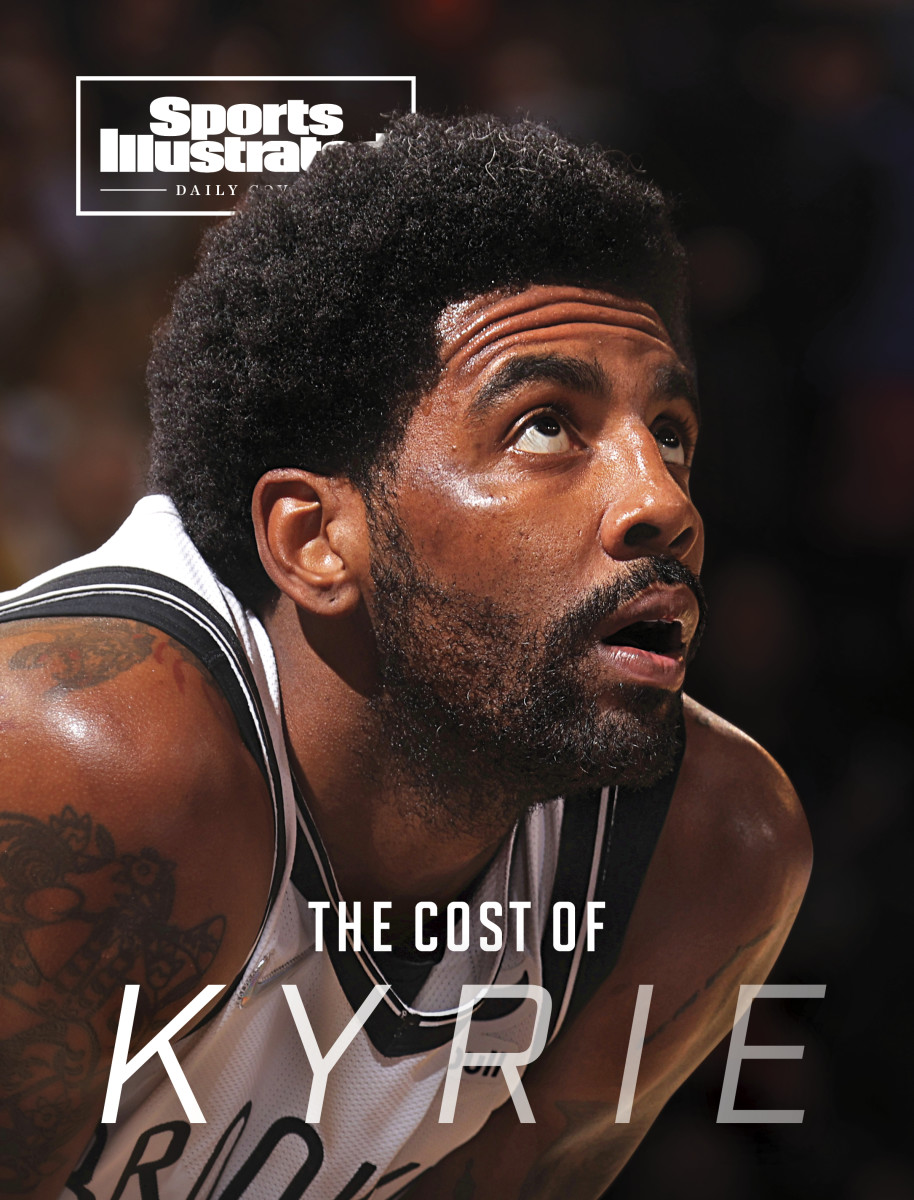

Kyrie Irving Has Put the NBA in a Postseason Predicament

It’s not about the vaccine. Sure, the vaccine seemed like the reason Kyrie Irving was the NBA’s most polarizing player this season. He refused to get the shot(s) that the science community recommended and New York City required of employees, which kept him from playing most of the Nets’ home games this year, and he became part of our national screaming match: He should get the vaccine, everybody should get the vaccine, he doesn’t have to get the vaccine if he doesn’t want it, some of these vaccine rules don’t make sense, whatever happened to freedom, etc., etc. But plenty of athletes have declined the vaccine. Irving drives people wild because of what he did to his team.

In the summer of 2019, Irving signed a four-year, $136 million contract with the Nets. In the three seasons since, he has played in just 103 of his team’s 226 games—partly because of injury, but mostly because of his own choices. Before the vaccine issue, he took a leave of absence with no explanation. Nets coach Steve Nash said he didn’t know where Irving was and general manager Sean Marks said he was “disappointed” Irving was “not in the trenches with us.” Irving later said it was a family matter. He also violated the league’s health and safety protocols. He seems to take great pride in having different priorities than the public expects from professional athletes, to the point where you wonder whether his priorities aren’t as important to him as being different.

Now here he is, heading into the postseason play-in tournament as one of the NBA’s most exciting players. The Nets have not really looked like a team all year, though. James Harden came and went. Ben Simmons came and hasn’t played. Still, the Nets are a dangerous 7-seed in the tournament, and this raises an uncomfortable question: If Kyrie Irving and the Nets somehow turn it on this spring and win a championship, what does that say about the league?

The NBA is in a weird place right now. It is undeniably thriving as a business and cultural entity, but as a competitive sport, it has lost its way.

In Michael Jordan’s last five seasons, he played a full 82 games four times—not because he was superhuman, but because that is what players did. In 2002–03, 46 players played all 82 games (including Jordan, who turned 40 that year and then retired for good). That was just the job: If you could play, you did.

Commissioner Adam Silver recently said he is looking into “a trend of star players not participating in a full complement of games,” but that’s an old tune. Five years ago he called stars sitting “an extremely significant issue for our league.” He is not much closer to a solution now than he was then. An in-season tournament would be fun and might motivate players to play more, but they would probably rest before and after it. Executives of winning teams have concluded it is more important for players to be healthy and well-rested than to have home-court advantage. Executives of losing teams would rather be terrible with young players than—oh, the horror!—try to put their best teams on the floor.

At these prices, fans should expect a team to try. And in the long term, they are trying. They’re just not necessarily trying on the night you show up with your kids.

Irving obviously did not create the environment where players skip games for reasons that have nothing to do with health. But the NBA is now a league where healthy players often sit out, sometimes for a long time despite making a ton of money. The Rockets paid healthy former All-Star John Wall more than $44 million not to play this year because he doesn’t fit their long-term plans. Everything Irving has done in Brooklyn, he did in a league where skipping games is part of the culture.

This generation of basketball has also been defined by player movement, which is an offshoot of player empowerment, which is a product of star players realizing that, while they are technically employees, teams really work for them. When LeBron James bounced from Cleveland to Miami to Cleveland to Los Angeles, he did so like a team owner shopping for a better stadium deal: LeBron James Inc. signed a four-year lease on South Beach, and then its CEO decided to move the offices again.

But when James does it, he always does it with basketball as a priority. So does Kevin Durant. James went to Miami to win his first title, to Cleveland to win there, to Los Angeles, at least in part, because there was no clear path to winning more in Cleveland. Durant joined a Golden State team that won 73 games, won two titles there, then left to prove he could win somewhere else.

Kyrie? He played in three straight Finals, had the best player in the world on his team and demanded a trade. He got traded to a Boston team that should have been on the rise, said he would stay there, then bolted to play with Durant for Brooklyn. That seemed like a move to win, but it is pretty clear now that it wasn’t quite that. For his whole career, Irving has been searching for something different.

“He's not your average jock, clearly, right?” says former New Jersey governor Richard Codey, who coached Irving briefly when Irving was younger and remains in contact with him. “You know, some of the things that he says are not what you expect, right? So what? That doesn’t make him a bad person.”

It does not. Codey says Irving is conscious of defining himself exclusively as a basketball player: “He knows, ‘I've got to start looking at the day that I’m not playing in the NBA. What will I be doing with my life?’”

Thinking about life after basketball … refusing to see himself as just an athlete … using his platform for philanthropy and social justice … that’s all great. The Nets, however, signed him to a $136 million basketball contract expecting him to play basketball.

It seems reasonable to think a highly paid professional athlete should show up to work on a regular basis, but Irving bristles at the notion we should see him primarily as a professional athlete, and he doesn’t seem all that worried about being highly paid. He forfeited his salary for home games, as part of an agreement between the NBA and the players association covering players who don’t comply with local vaccine mandates. His lack of availability these last three years should make teams wary when he hits free agency again. (When the Nets decided to sit him for all games, they kept paying him for the road games he would have played.)

Since Irving doesn’t appear to be preoccupied with what we think he should care about, it is easy to assume that he would be just as happy to lose early and have a free summer to see whether he can find the end of the Earth. But perhaps because he doesn’t need basketball, Irving can play at an incredibly high level in high-pressure situations.

We never really saw what Irving could do with Durant and Harden, and we still haven’t seen what he can do with Durant and Simmons. But we saw what he did with James. There were many times in the last few years when Irving did not seem all that interested in his team. He did some things that never would have worked in the NBA of 20 years ago or in the NFL of today. His team stuck with him anyway. That might turn out to be worth it for them. But what is the cost for the league?

More SI Daily Covers:

• The Inevitability of Cade Cunningham

• Nikola Jokic Gets Lost Among the Stars. And He’s O.K. With That.

• Behind Ja Morant’s Sudden Ascent to NBA Superstardom