Inside the Celtics’ Dramatic Turnaround From Under .500 to NBA Finals

As the horn sounded to end the third quarter of Game 1 of the NBA Finals—a brutal 12-minute stretch that saw the Warriors gash the Celtics’ vaunted defense for 38 points, turning a two-point halftime deficit into a double-digit lead—Ime Udoka stormed into his between quarter meeting with his assistants, the exasperation visible behind his mask. “We’re letting them go wherever they want to go,” Udoka grumbled to his staff. The numbers were ugly: Golden State shot 44% from the floor and 46.2% from three. Boston connected on just 37% of its shots while committing five turnovers.

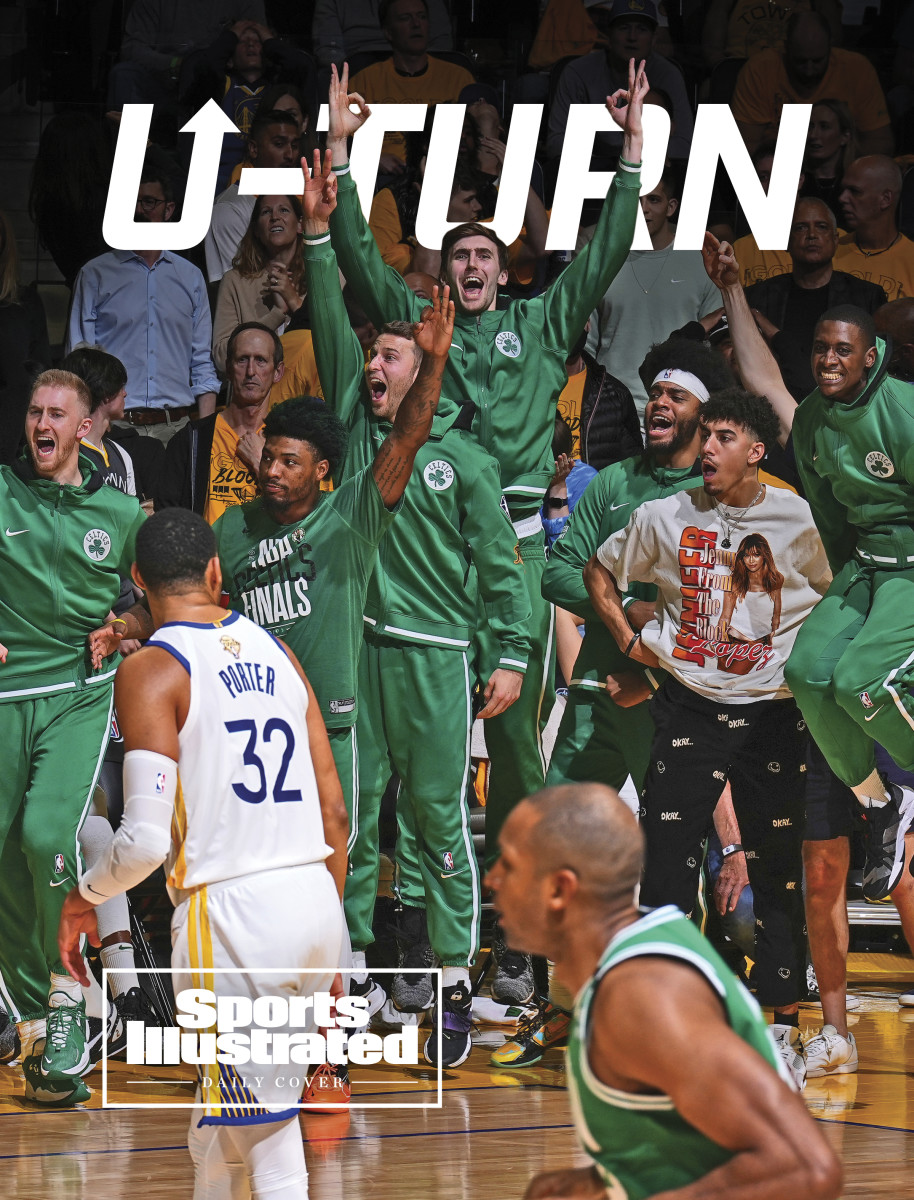

On the bench, Jayson Tatum delivered a terse message to his teammates: We’ve been here before.

Here was on the receiving end of a third quarter shellacking. It was familiar ground. Boston was here in Game 3 of the conference semifinals, when Milwaukee ripped off a 34–17 third quarter. They were here in Game 1 of the conference finals, when Miami scorched the Celtics in the third 39–14. Third quarters have become a sinkhole of sorts for the Celtics in these playoffs, one they have found impossible to avoid.

Settling into a seat in front of his team, Udoka was more blunt. They’re punking us right now, Udoka said, comments first reported by Yahoo! Sports. Is this the way you want to go out? It was a sharp critique, though not an unfamiliar one. Since taking over as head coach, replacing Brad Stevens, who ended his eight-year run last June to succeed Danny Ainge as president of basketball operations, Udoka has operated with a candor rarely seen in the NBA. In October, Udoka called Jaylen Brown’s early season inconsistency “mind boggling.” In November, Udoka criticized Tatum for failing to impact the game beyond his scoring. In December, after Clippers rookie B.J. Boston scored 27 points to power undermanned L.A. to a win, Udoka blamed his team for not reading the scouting report. In January, after the Celtics coughed up a 25-point lead in a loss to New York, Udoka matter-of-factly declared that his team lacked mental toughness.

“That’s a hundred percent who I am,” Udoka says. “As long as the players were O.K. with it, I was fine being myself and coaching us that way. I’m not the person that sweeps anything under the rug. Everything I did say in public was said multiple times in private. So there was nothing I surprised them with.”

Still, whether it was Udoka’s approach or his system, Boston struggled to start the season. Mightily. The Celtics lost their opener in New York. Two days later, against Toronto, they were booed off their home floor. They were outscored 39–11 in the fourth quarter in a loss to Chicago, after which a frustrated Marcus Smart vented that Tatum and Brown “don’t want to pass the ball.” They shot 9.5% from three in a loss to the Clippers. In late December, the Celtics traveled to Minnesota to play a Timberwolves team that was without Karl Anthony-Towns, Anthony Edwards and D’Angelo Russell. Minnesota won by five. One executive told ESPN that Boston was “stuck in neutral—and maybe going backwards.” Debate shows wondered whether Tatum and Brown should be broken up.

“Those days,” said Al Horford, “were very dark.”

On January 1 the Celtics were 17–19, lingering among the teams battling for a play-in berth. Of course, they closed the season 34–12 and are now three wins away from the franchise’s 18th championship. The story of how they did it involves a coach pushing the right buttons, an executive making the right deals and a roster that stopped fighting Udoka’s methods and finally coalesced.

Udoka insists: The Celtics were never as bad as they looked early in the season. “You would see really good steps that we would take, some growth,” says Udoka. “And we all saw the games early in the season where we played extremely well, sharing the ball. And the next game, it looks like we never did it before. And so how to have carryover, that was a big thing to stay consistent with that.”

Udoka inherited a team with talent. Tatum was an All-NBA forward. Brown made his first All-Star team in 2021. Smart had established himself as one of the NBA’s premier defenders. The Celtics were just two seasons removed from a trip to the conference finals.

Yet Udoka knew this team needed to grow. For two years Udoka had a birds-eye view of Boston. He spent the 2019–20 season on Brett Brown’s staff in Philadelphia. He worked the following year as one of Steve Nash’s top assistants in Brooklyn. In ’19 he was an assistant with USA Basketball—a team Tatum, Brown and Smart played on. At his introductory press conference, Udoka, with Stevens sitting beside him, noted the Celtics were 27th in assist percentage last season. “Sorry to mention that, Brad,” said Udoka, sheepishly. In Tatum and Brown, Udoka saw a pair of high-level talents who, he says, “were pretty one-dimensional.”

“I just wanted to add to their game, add layers,” says Udoka. “When you look at guys that have that ability to get to wherever they want on the court, but really have tunnel vision, that was the biggest thing offensively. How can we get them both to be better playmakers? And that was the goal of the year.”

Getting both to buy-in was challenging. “Honestly, that’s what took the longest,” Udoka says. “Everything they had done up until this point that brought them success was one-on-one-based.” Tatum shot 39% in November. Brown shot 41% in December. COVID-19-related absences—the Celtics ranked in the top five in games lost due to players landing in health and safety protocols in the first two months of the season—hindered the team’s efforts to develop chemistry. And with its two stars struggling, Boston sank in the standings.

“It was very frustrating,” Tatum said. “You know, head-scratching. It was more so, ‘How can we figure it out?’ There were definitely some tough moments. I always remember the fun moments. My first year going to the conference finals, the bubble year going to the conference finals when we were winning all the time. Beginning of this year, every game was like, ‘I don’t know if we’re going to win.’ It was a lot tougher than it should be, and that’s something I wasn’t used to.”

Listen to an audio version of this story on the SI Weekly podcast

Then there was the defense. Under Stevens, the Celtics played more traditionally, often pushing players to get through screens rather than switch on them. Some of it was by necessity. For years Boston functioned with a below-average defender at point guard; Stevens would have to account for teams targeting Isaiah Thomas, Kyrie Irving and Kemba Walker. When the Celtics traded Walker, the job fell to Smart, Boston’s best defender.

Udoka championed Smart early. Drafted as a point guard, Smart spent his first seven seasons in a utility role. In Smart, Udoka saw the potential to be defensively versatile. But he also saw a lead guard hungry for an opportunity. “He’s a natural leader,” says Udoka. “He fit with the group better in this role. A guy that wasn’t looking to score first. Our group needed that.” Like Boston, Smart struggled early, shooting 27% from three in December. Teammates chafed at his public criticism. Smart, though, insists he never lost confidence in the team.

“I know this may be hard to believe, but I was even more confident in those first two months,” Smart said. “Just for the simple fact that I knew everything was new. We were all changing and trying to adjust. Once things start to click, for me, the ability that I bring to this game on that point guard position would be noticed tremendously. So for me, I was just excited to have the opportunity to show what I can do with the keys to the ship.”

Smart’s ascension to starting point guard gave Boston plus defenders at every position. But the Celtics, accustomed to Stevens’s defenses, were slow to embrace the systematic change. Tatum, Udoka says, came to him during the first week of training camp with reservations about the style of play. “It was definitely something we had to get used to,” said Grant Williams. Udoka’s message: Stick with it. “You had to fight some of that off early in the season with guys questioning a few things,” says Udoka. “It takes communication and discipline and dedication. But I think it's really easier than locking into a guy, chasing a guy off ball, chasing through every pick and roll. If we could switch and communicate properly based on our personnel, I thought we'd be really good.”

Personnel was Stevens’s department. Stevens was an unconventional choice to succeed Ainge. A career-long coach, Stevens ascended to the job with no front-office experience. But he knew the team. He knew it needed Udoka, whose résumé—ex-player, longtime assistant—differed from Stevens’s, as did his coaching style. He knew they needed Horford, who previously thrived in three seasons in Boston. In February, Stevens flipped Dennis Schröder for Daniel Theis, moving out a ball dominant guard while bringing back another ex-Celtic familiar with the personnel. Stevens also acquired Derrick White, adding a versatile, unselfish playmaker—one Udoka had coached in San Antonio. In the Horford and White deals, Stevens surrendered draft capital—something Ainge was loath to do—to upgrade the roster.

Udoka describes his experience working with Stevens as “totally positive.”

“It’s two guys with no egos that see things similarly basketball wise,” says Udoka. “I will lean on him for advice. He was the first to kind of let me get my feet wet and do some things. He would see some things and give me examples of things he went through with these guys. But at the end of the day, the great thing about it is he does step back and let me do my thing. And he knows we coach differently, so something he may give me as far as advice I handle differently. We both have the same goal—to win.”

When the Celtics became good depends on who you ask. For Udoka, it was New Year’s Eve when Boston, still reeling from a three-game losing streak, beat Phoenix by 15. “It was our best off ball night,” says Udoka. For Horford, it was early February. “I was seeing something different with how we were playing,” says Horford. In games played after January 1, the Celtics were first in defensive rating (105.2), net rating (12.7) and scoring margin (plus-12.7). “There's not a guy who comes on the floor who isn't giving 110% on [the defensive] side of the ball,” said Draymond Green. In March, Boston swept a four-game road trip, clobbering Golden State, Sacramento and Denver by double digits along the way. Tatum finished the season the NBA’s leader in plus/minus (plus-667). Smart won Defensive Player of the Year.

“I’m sure not many people thought we would have gotten to this point,” said Tatum. “But there was always a sense of belief between us and the group that we were capable of figuring it out.”

What’s changed?

Green paused to consider the question. In December, the Warriors, catching the Celtics near the bottom, picked up a win in Boston. In March, against a Celtics team that was peaking, Golden State absorbed a 22-point home loss.

“They’re just more sure of themselves,” Green said. “You know, they’ve had time to put it all together. I think the big difference is now they know who they are, they know what they're trying to get to, they know what makes them successful.”

Indeed, the adversity Boston faced early in the season hardened them for this playoff run. It brought Tatum and Brown closer together. “Just to prove that we can win and put ourselves in a position to do that,” Tatum said. Udoka repeatedly prodded Robert Williams early in the season to play more through pain. “I’m one of those guys he can say stuff like that to,” said Williams. Last month, Williams returned to the lineup a month after undergoing knee surgery. Against Milwaukee, Williams recalled Udoka challenging him to stop letting the Bucks “f----ing run you over.” Since his return, Williams has played through the kind of swelling and pain that would ordinarily sideline him for weeks. Said Williams, “He knows I respond well when he challenges me like that.”

On Wednesday, Udoka will challenge Williams and the rest of the Celtics again. Boston stole homecourt advantage with its Game 1 win. But the Celtics were outscored by a combined 35 points in the third quarter of both games. In Game 2, the Celtics committed 19 turnovers that led to 33 points. That kind of sloppiness has routinely meant disaster: Boston is 12–2 when allowing 18 or fewer points off turnovers, 1–5 when they give up 19 or more.

“We don't turn the ball over, we give ourselves a better chance to win,” Tatum said. “That's not rocket science.”

Rocket science could be a problem. For the Celtics, overcoming adversity, any adversity, so far has not.

• Steph Curry Is Dominating the NBA Like Never Before

• Heat’s Erik Spoelstra Is at the Peak of His Powers

• The Warriors’ Daring Quest to Extend Dynasty Run