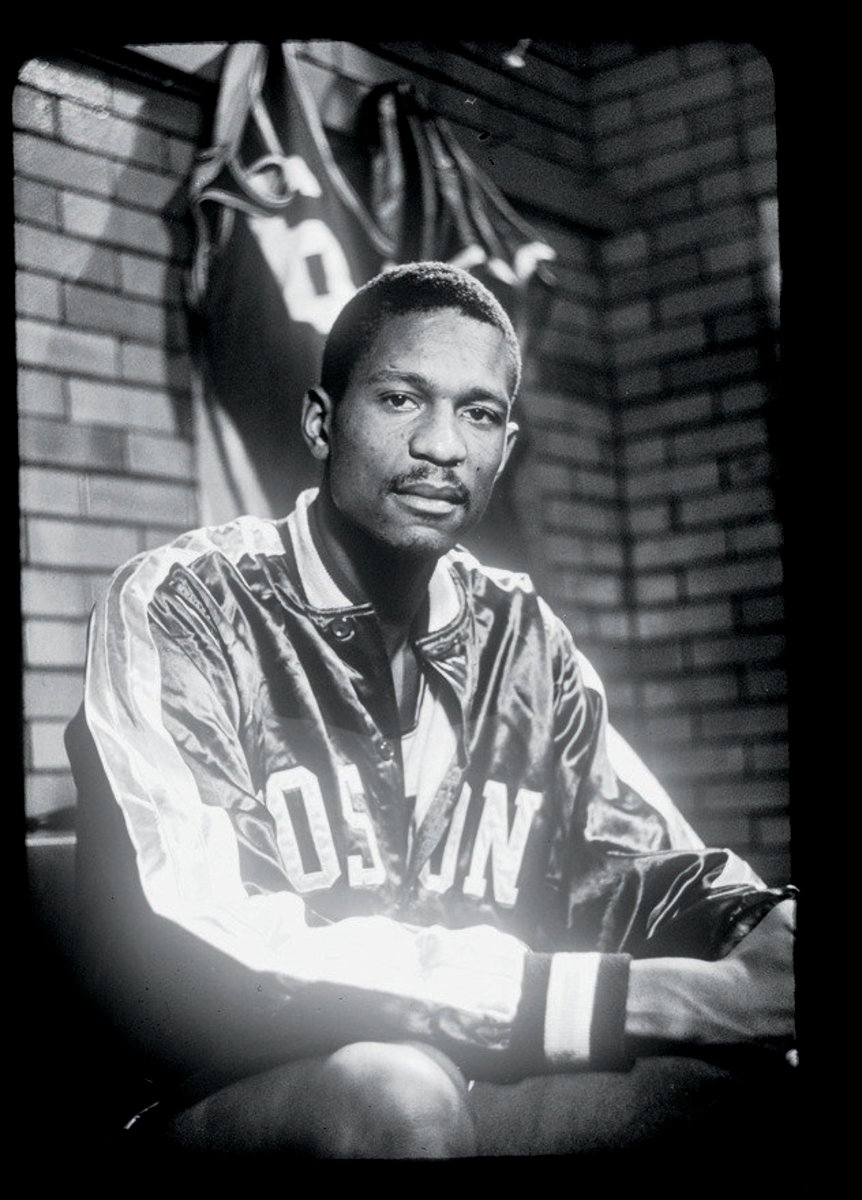

Bill Russell’s Off-Court Example Is What Resonates Most, Now and Beyond

It would be reductionist to talk about the late Bill Russell through only the prism of some of the worst, ugliest things that ever happened to him. After all, Russell—who died Sunday at 88— was, and still is, the greatest winner in the history of major professional American sports, and a barrier breaker in every sense of the word.

The reality of Russell’s legacy as a human is that you can’t fully sum him up without understanding the incredibly racist current he swam against in the 1950s and ’60s, even while being the greatest to ever play his sport to that point in time, and eventually becoming the first Black coach in NBA history.

This was a man who led the Celtics to 11 championships in 13 seasons, yet had an enormously complicated relationship with the fans in Boston. Large swaths of the area’s media and fans had pegged the city’s first Black sports star as surly, due to the fact that he initially turned down his induction into the Hall of Fame and his longtime refusal to sign autographs for fans. (The autograph detail was even cited in a file the FBI kept on Russell. The file called Russell “an arrogant Negro who won’t sign autographs for white children.”) In 1963, in the midst of the decorated title run, Russell returned to his suburban Boston home from a weekend trip only to find that it had been broken into and vandalized, with racial epithets spray-painted onto the walls, and his beds defecated on.

The racism obviously wasn’t isolated to Boston during these years. Just two years before, in 1961, Russell and three other Black players for the Celtics—Sam Jones, Thomas “Satch” Sanders and K.C. Jones—told legendary Boston coach Red Auerbach they’d be boycotting an exhibition game after an incident in which Sanders and Sam Jones were refused service in their coffee shop at the team hotel in Lexington, Ky.

The Black members of the St. Louis Hawks sat out in solidarity. But the game played on anyway, as every white member of the two teams—including seven white Celtics players—opted to compete. Hall of Famer Bob Cousy, a legend in his own right and perhaps a more popular player among Celtics fans during the first half of Russell’s career, has expressed guilt for not doing more to back up or advocate for Russell in those years as he faced racism. (In 2015, Cousy wrote Russell a letter, apologizing for not doing more. During a 10-minute phone call with Russell in 2018, Cousy asked Russell whether he ever received the letter. “Yes, I did; thank you,” Russell said, adding nothing more.)

“I am coming to the realization that we are accepted as entertainers, but that we are not accepted as people in some places,” said Russell—who went to Mississippi in the wake of Medgar Evers’ assassination in 1963 before taking part in the March on Washington later that same year—at the time of the holdout in Lexington.

The lack of universal acceptance led Russell to become closed off in a way many weren’t, particularly with fans in Boston. In 1972, he asked that his jersey be retired privately, in front of members of the organization only, as opposed to in front of Boston fans. “The only way he was going to participate would be if it was before the game,” recalled the late Tommy Heinsohn, a Celtics legend and Russell teammate. “He respected his teammates, and that’s why he did it the way he did it.”

Russell himself explained the dichotomy to his daughter, Karen, at one point. “I played for the Celtics, period. I did not play for Boston,” he told her, according to a 1987 New York Times opinion piece she wrote. “I was able to separate the Celtics institution from the city and the fans.” (Russell moved out of Boston immediately after his playing career ended in 1969, heading to the West Coast, where he lived out the rest of his life.)

For as much as the hyperathletic Russell elevated his sport—literally taking the game of basketball and making it more vertical and above the rim than horizontal for the first time in its history—he helped to push civil rights and the interests of Black athletes to the forefront just as much, if not more. He spoke out concerning segregation in the Boston school system and was one of the highest-profile backers of Muhammad Ali in his refusal to serve in the Vietnam War, a stance that was heavily criticized in the United States at the time.

Interestingly enough, 40 years later, Russell took a similar stance by backing then 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who sparked a firestorm of criticism for kneeling during pregame national anthems as a way of protesting police brutality and racial inequality. In recent years, Russell posted a picture wearing an “I’m With Kap” jersey. In a separate post, back in 2018, Russell took a knee in the aftermath of unarmed 22-year-old Stephon Clark being killed by two Sacramento police officers. And Russell’s holdout from 1961 looked somewhat prescient in 2020, when NBA players opted against taking the court in the immediate aftermath of the police shooting Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wis.

These issues were ones that always mattered to Russell, who in 2011 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom—the highest civilian award in the U.S.—by then President Barack Obama. Russell gave the sport, and society at large, so much more than it gave him at times. He did the difficult, sometimes ugly work as an activist, and likely enjoyed less fandom than he otherwise would have received from some because of his stances and his dedication to the cause.

He is beloved by this current generation of players, an often socially conscious group that acutely understands the weight of its words and actions in the public sphere. And despite how Russell changed the sport for the better on the court, it’s arguably his actions away from the hardwood that reverberate most loudly in today’s game.

More Bill Russell: