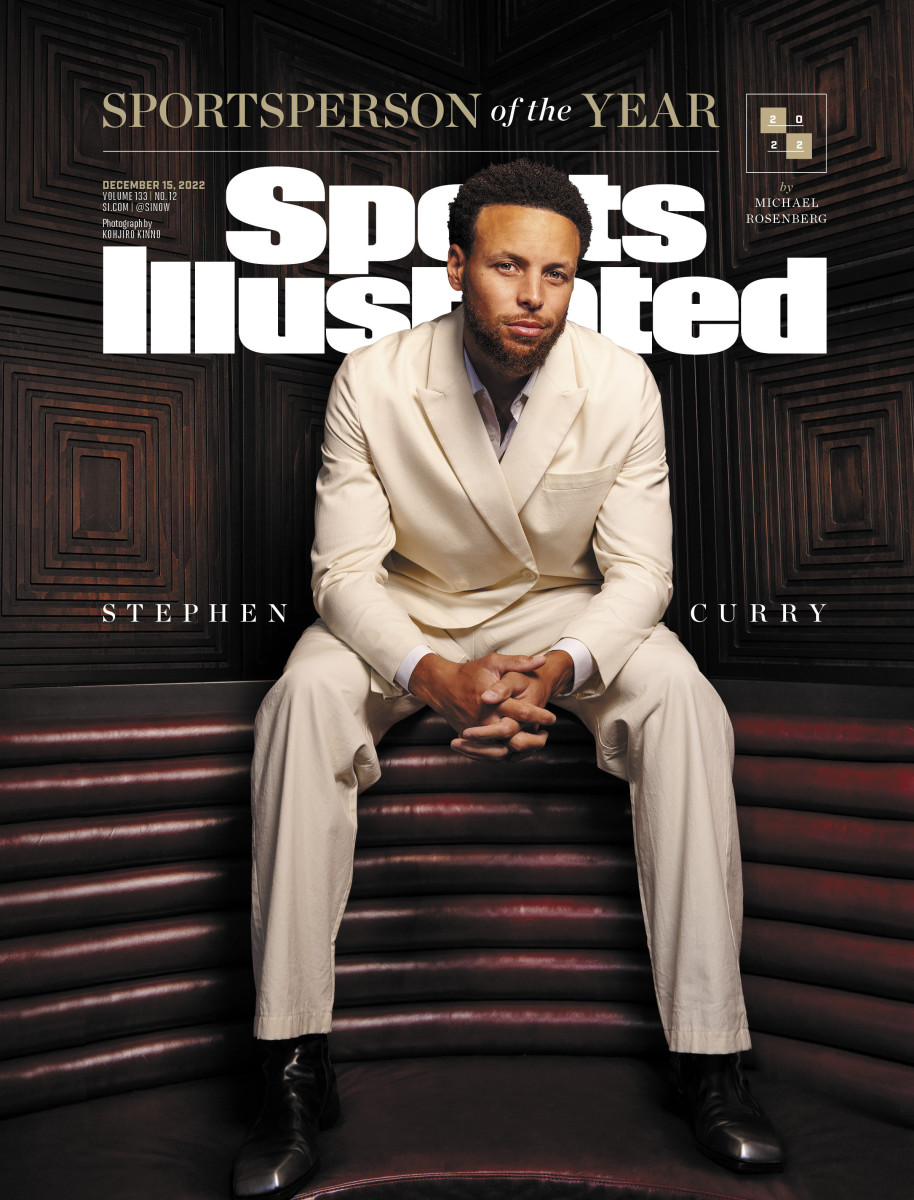

Stephen Curry Is SI’s 2022 Sportsperson of the Year

Stephen Curry walked to the bench lugging a superstar’s dilemma: He had played poorly, but his team was going to win. Seventy-nine seconds remained in Game 5 of an NBA Finals that had been framed—to an illogical degree, in Curry’s mind—as a referendum on Curry’s career. If he was truly one of the best players of all time, why hadn’t he won a Finals MVP award? Curry is driven by winning and by lifting others—motivations that are fraternal, not identical, twins. The Warriors would win this game, but he had not lifted them. Curry sat down next to coach Steve Kerr, at the intersection of pride and selflessness. He seemed, Kerr says, “pensive more than anything.”

As much as ever, Curry was in the spotlight, and yet still people did not really see him. If he thinks about his place in history, he never says it, and he found the Finals MVP conversation annoying: “It bothered me that I had to answer to it. It didn’t bother me that it wasn’t on my résumé yet.” The idea that he is lacking something is foreign to him. The implication that he needed to prove himself on the biggest stage was silly.

Get SI’s Sportsperson of the Year Issue

Curry is a boisterously ostentatious performer, and confidence is his oxygen. He once missed his first nine three-point attempts in a playoff game and when he sank the 10th he shimmied. As the Celtics finished off Game 3 to take a 2–1 series lead, Curry told them to their faces to enjoy their last win. Then he told his childhood friend, Omar Carter, he wanted to celebrate in Boston—meaning the Warriors would win three straight and wrap up the title in Game 6. Now they had won Game 4 and were about to take Game 5 in San Francisco.

Kerr turned to his star.

“This is like the best thing that possibly could have happened,” Kerr said.

“What do you mean?” Curry asked.

“We just won this game going away when you had a tough night,” Kerr said. “Do you know how that makes Boston feel?”

Curry thought about it, agreed his coach was right and made the kind of small recalibration that comes so easily to him. Before this year, Curry had not won a playoff game since 2019. His Splash Brother, Klay Thompson, had missed two and a half seasons because of injuries. Curry turned 34 in March. After Game 5, in his suite under the Chase Center, Curry received another reminder of time passing: His college coach, Bob McKillop, informed him he was retiring.

Curry came out in Game 6 and made the Celtics feel even worse: 34 points on 21 shots, seven rebounds, seven assists, two steals, one block and one more championship. It required an indomitability even beyond what he showed in winning two MVPs and his first three championships. He calls it his “greatest moment,” and even this modest brag is so unlike Curry that his wife, Ayesha, says, “Really—he said that?” At the Warriors’ afterparty, in a club underneath TD Garden, Ayesha said, “I’m so proud of you! You did it!” Steph corrected her: “We did it.”

Curry knew people had said the Warriors were finished. He says, “I’m an internalizer. I internalized that throughout the entire year, the last three years. … Just let it marinate.” In the euphoria after Game 6, he uttered one of the most viral sports comments of the year:

“What are they gonna say now?”

It was interpreted as Curry shutting up the doubters. He was also dismissing the nitpicky nature of the whole Finals MVP criticism. Curry admits, “I definitely log receipts,” as most greats do, but he does it only because the receipts are useful. As a lightly recruited kid and overlooked young NBA player, he was easily motivated. After he became a widely praised superstar, he had to manufacture reasons to bust his ass in January and July, even though he knew it was just a motivational game he was playing with himself.

“It’s like a hybrid car,” Curry says. “Once the juice runs out, you gotta go to the reserve tank a little bit.”

He says the ensuing discussion about slaying his haters was “almost a little awkward.” The story of the Finals became about how critics had affected Steph Curry. But the story of his life is how he affects everybody else.

This is What Steph Curry did this year: He won his fourth championship. He won that Finals MVP award after scoring an efficient 31.2 points per game against the best defensive team in the league. He graduated from Davidson, 13 years after he left for the NBA following his junior season. He expanded his charitable reach: Since 2019, the Eat. Learn. Play. Foundation he and Ayesha founded has served more than 25 million meals to food-insecure children, spent $2.5 million on literacy-focused grants and distributed 500,000 books, according to Curry’s representatives. He has also provided seed funding for men’s and women’s golf teams at Howard University, a historically Black school, and started the Underrated Golf Tour, a junior circuit designed to make the game more inclusive. He is co-chair of Michelle Obama’s When We All Vote initiative. And now we name him Sports Illustrated’s Sportsperson of the Year. Curry, who also shared the award with the 2017–18 Warriors, joins LeBron James, Tom Brady and Tiger Woods as the only multiple-time winners. We salute him this year not just for what he did, but for how he did it.

On a daily basis, Curry pulls off one of the toughest tricks in sports: He passionately seeks greatness without being consumed by it. He reminds us that stardom is not a license to be a jerk, and being a jerk is not a prerequisite for stardom. Longtime NBA fans can recite many stories about Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant belittling teammates to motivate them. There are no such stories about Curry. He can go weeks without giving anybody a pep talk, and, when he does, it’s usually pretty short: Come on! Lock in!

“Winning is fun,” Curry says. “We all know that. But to do it in a way that people speak on our culture, speak on my leadership, you have the respect of people around you—like, all that stuff matters in the big picture. And it’s hard to do.”

The only people Curry wears out are the ones defending him. Everyone else, he boosts. There are a lot of highly driven people in pro sports, and plenty of sweethearts, but who else besides Curry is both all the time? He says the losses in the 2016 and ’19 Finals sit with him more than the wins: “I still can put myself in those moments or feel that sense of emptiness. I feel that more now, looking back, versus the other ones for sure. That’s the age-old conversation, right? Like, I think Jordan has articulated that. Kobe as well. For me, they go hand in hand.” Still, his friends say his demeanor is the same after wins as after losses. Curry hears the criticism but says, “I don’t carry it home.”

Bob Myers, the Warriors’ general manager since 2012, says he has seen him down once—in the ’19–20 season, when Curry had hand surgery, Thompson had a torn ACL and the Warriors had no immediate hope.

Many people who know him call him the best person they know, and yet, because so much of Curry’s character is tied to not acting special, they are hesitant to make too much of a fuss about it. Jason Richards, who was two years ahead of Curry at Davidson, tells anybody who asks that Curry is a better person than a player, but casually refers to him as “the kid.”

Ayesha says, “I don’t know that I’ve ever seen him angry. He’s not argumentative. He never gets to that point. He’s always able to take a step back outside of himself and look at multiple sides. … As a human being, it’s a beautiful thing to watch, but as his wife, it’s kind of annoying.” She laughs. “It’s like, ‘O.K., Mr. Optimist!’ ”

Sportsperson of the Year Winners

This Curry self-assessment won’t go viral like his post-Finals comment, but it sums him up as well as anything: “I don’t need anybody to tell me I’m great or anything like that. I have a very high sense of self-confidence and what I can do. But there’s also the self-awareness, too: You’re not doing anything great in this world alone.”

He is so comfortable with himself that he doesn’t waste time on his ego. McKillop says, “If you text him or call him to say, ‘Great game, great this, great that,’ he won’t respond. If you say, ‘I hope you treat Ayesha like a queen today. Happy anniversary,’ he’ll get back to you.” Richards, who is Underrated’s director of athletic operations, says when his friends meet Curry for the first time, he gives them a warning: “Just so you know, he is going to make eye contact with you whenever you speak.” When Curry talks to his high school coach, Shonn Brown, he is more likely to ask about Brown’s team than mention his own. As a rookie, Curry walked down Bay Area streets quietly handing out $100 bills.

When you talk to him, he doesn’t fiddle with his phone. Curry asks just about everyone he meets: “How are you?” He listens to the answer.

Kerr, who won three championships with Jordan’s Bulls, says Curry cares deeply about giving fans the best Steph Curry he can muster: “They feel responsible. Jordan used to feel the same way. He felt responsible for putting on a show in front of the fans in Milwaukee who are only going to see him once or twice, whatever it was.” Curry tries to carry this over to every interaction with the public. He told Carter, his longtime friend, he has a simple aspiration: He wants to make sure anybody who talks to him “has a good experience.”

Myers has won four NBA titles with the Warriors, but he says working with Curry “will be probably the biggest blessing of my professional career. Not the winning. I mean, the winning is great. But the man, the person. … I really marvel at him, because a lot of his attributes, I cannot identify with. I don’t have that ability to see happiness all around.”

Here is a story you could tell about almost nobody else. When Curry played high school ball at Charlotte Christian, he and his fellow captain felt the team should bench a returning starter. Brown, their coach, agreed, and told the captains they had to deliver the news. Curry was not eager to do it, but being captain is not an à la carte job: You can’t just pick and choose the tasks you enjoy. So Curry did it.

The other player was so angry that, on the court before practice one day, he went after Curry. There was Steph, on the ground, in a headlock, his face reddening. Curry did not fight back. He waited for the kid to release him, and, when he did, Curry got up and … said a few quiet words to him. Then he went back to practice shooting.

What is that? How many of us could summon that kind of empathy for somebody who is physically attacking us, in the moment of the attack? That was Curry as a teenager.

“He’s got an emotional stability that sort of overrides the day-to-day emotion of the team,” Kerr says. “He’s our foundation. He allows us to get through everything—and we’ve been through a lot. Without him, this would have unraveled years ago.”

In 2016, when the Warriors wanted to sign Kevin Durant, Curry helped recruit him, unconcerned about whether Golden State would be his team or Durant’s. They won two titles together and nearly won a third, with the public dissecting their relationship every day until Durant left for Brooklyn.

Once he got healthy, Curry returned to All-NBA form and his standing in history. Last December he broke the NBA’s career three-point record. In the past, he might have downplayed it and moved on; Ayesha says, “There was a period of time where you’d be like, ‘Do you realize what just happened? You just won a championship. You should probably take a moment to celebrate.’ ” But this time, he celebrated with a gathering of around 75 people at Catch Steak in New York City.

Steph sat between his dad and his college coach, and he was the only one who gave a speech—so he could thank everybody who had helped him. Alabama quarterback Bryce Young, who had just picked up his Heisman, was there. Kerr wasn’t sure whether he was invited, didn’t ask, didn’t go and didn’t worry about it. He knew Curry doesn’t keep score in his social life. But one person who did show up was Durant. For all the public dissection of their relationship and what it meant for their legacies, they remain on great terms. Curry had given Durant a good experience.

Even a championship NBA season is full of headaches, and Curry provides the Tylenol. When Draymond Green coldcocked Jordan Poole in October, Curry tried to play peacemaker—by listening more than lecturing. Ayesha says, “I think that was one of the first times I’ve seen something shake him because he cares.” When the season began, Curry was his usual All-NBA self, but the Warriors struggled. It will fall to him, once again, to mend and elevate. He says: “Empathy is a great word that you try to embody through the good times and hard times. It comes from a place where there’s no judgment, based on who you are, where you come from, what you bring to the table.”

This is what Steph Curry did not do this year: He did not make a big deal about now having twice as many titles as Durant. He did not publicly state his case as one of the top two players of this era, alongside James. He did not point out that he easily could have been—and arguably should have been—the 2015 Finals MVP ahead of Andre Iguodala. (Durant won the trophy in Golden State’s other two title runs.) He did not complain that Green’s preseason punch put him in an unfair position. He did not push the Warriors to trade one of their young potential stars for veterans who could help him win another title. Every year, as the trade deadline approaches, Myers asks Curry what he thinks, and he says Curry will “laugh and say, ‘You’re better at this than I am. So just whatever you think.’ Which is kind of crazy, right? He could abuse that power and he would get away with it. He never does.”

This summer, when Green said on his podcast that Curry “got double-teamed probably seven times the amount that KD did in a given series” when they were together, Durant fired back on Twitter: “From my view of it, this is 100% false.” But Curry did not enter the fray. He didn’t do any of that because he doesn’t need to. Genuine confidence does not require outside affirmation.

“We don’t win those championships unless I’m playing at the highest level,” he says of not winning Finals MVP before. “But also: Andre, KD, they deserved the award because of how they played.”

In a world that rewards relentless self-promotion, Curry is a confusing case, because he says and does things on the court that he would never do off it. He talks trash. He revels in his success—turning to face an opposing bench before his three-pointer tickles the net, doing his (relatively new) “night-night” celebration after sealing a win. He is so much fun to watch, in part, because he has so much fun being watched. But then he walks off the court and quickly starts deferring to everybody else. He does not play basketball to prove a point. The fun is the point.

“The pure joy I have on the court, it’s like a spacey kind of attitude. … Like, I’m not thinking of anything other than just hooping and having fun,” he says. “That’s why I have all these mannerisms and joy and happiness out there, because I’m kind of just lost in the game.”

That kind of balance is why the Warriors keep rolling in an era when nobody keeps rolling for long. Kerr says, “There’s lots of players around where you’re constantly having to think about their needs. We don’t have to spend any energy on that, because he’s so self-assured and so happy and confident in himself, in his own skin.”

Kerr once forgot to mention Curry when speaking at a championship parade. No big deal. During the Durant years, a radio host asked Kerr whether Durant or Curry was the better player, and he chose Durant. More interesting than Kerr’s opinion was that he shared it publicly: “I knew saying that, that Steph wouldn’t mind. Part of his power is his humility, his awareness of the team dynamics and who needs to hear what.”

But about that answer, Steve ...

“KD, to me, remains even now the most talented player in the league,” Kerr says.

“His frame, his size—6'11"—his ability to protect the rim defensively and then get any shot he wants offensively.

“But Steph was more impactful to our team because of the pace and because of the frenetic flow of his game, and how everybody chased him everywhere and how much it opened up. We’ve always struggled without Steph, where we’ve been able to win a lot of games without other key guys, including Kevin. So to me, it’s two different questions.”

Kerr did not fully appreciate Curry’s gifts until late in their first season together, 2014–15, which ended in a championship. Curry makes so many plays from so many places, and commands so much attention from opposing teams, that he frees the court for everybody else.

Kerr was just one in a long line of people to underestimate Curry. At 6'2", Curry is five inches taller than the average American man, but he looks small on an NBA court. No matter how much facial hair he grows, he looks young. No major-conference school recruited him, general managers holding the first six picks in the 2009 draft passed on him and he perpetually seems like he is starring in a sports-fantasy movie in which the littlest kid is granted a wish to be better than everybody else, smiting giants by slingshotting basketballs through the net from 30 feet away, then grinning like he won a toy at the state fair. The average person cannot imagine being Giannis Antetokounmpo, but Curry is relatable. It all disguises what Kerr says is the truth about Curry: “He’s one of the great athletes in the world.”

Kerr sometimes brings footballs to practice, just to keep the team loose, and he describes Curry’s throwing arm as “an absolute cannon.” McKillop saw Curry play baseball when he was in middle school and says, “I swore he was the next Alex Rodriguez or Derek Jeter. I swear he could have been in the major leagues. I swear to God.” When Curry took batting practice with the A’s a few years ago, he hit a home run; when he pitched BP and somebody hit an infield pop-up, Curry jogged over and casually caught it bare-handed behind his back.

Once, Kerr surprised the team while on a road trip in Minnesota by canceling practice and taking the team bowling. Warriors assistant coach Bruce Fraser says Curry started out “strike, strike, strike”—all of them starting by the gutter and spinning back toward the center of the lane, PBA Tour–style. “I’m looking at this guy: ‘That’s not fair,’ ” Fraser says. Curry’s team won, of course.

When DeMarcus Cousins joined the Warriors in 2018, he watched Curry sink a pair of flip shots—way up high in the air, then right down through the net—and looked at Curry like he had won the lottery two weeks in a row. Fraser explained to Cousins: “That’s not lucky.”

“When you look at the world through your own lens, as everyone does, you can’t fathom what that kind of hand-eye is,” Fraser says. “You just cannot. It’s almost like an eagle that sees a mile. That little thing, that far away … like, you can’t even imagine what that is. This guy has that.”

Curry’s hand-eye coordination is especially apparent in golf, a sport he doesn’t play nearly as often as he would like. Everybody knows Steph loves golf, but you might not realize how much: A few years ago when he landed awkwardly on his right foot in garbage time of a regular-season game, his first thought was that he would miss his tee time the next day. Curry is a plus-one handicap, meaning he is expected to break par; he bemoans a pair of recent 77s that damaged his handicap, which means 99% of golfers reading this sentence now resent him.

This summer, in the first round of the American Century Championship celebrity tournament in Tahoe, Curry holed out from 97 yards on the 13th hole. The next day, he got to 13 and hit his drive in the fairway again. As he walked to his ball, his playing partners, Justin Timberlake and Aaron Rodgers, were talking about how loud the roar was when Curry made eagle the day before. Curry promptly hit his approach to within a foot of the cup.

“I think the traditional opinion is [that] a guy who runs the fastest and jumps the highest is the best athlete,” Kerr says. “I think that is one form of athleticism, but the other one that I think is at least equally as important—in basketball, more important—is hand-eye coordination, balance, focus, intensity.”

The myth of Curry as an ordinary athlete is self-perpetuating. Every time somebody underestimates him because of his appearance, it becomes easier to see him as one of us. It helps that he acts like one of us, too. When he left Davidson, he promised he would graduate, a vow he took more seriously than anybody realized. After his rookie year, he went back to Davidson all dressed up to watch his classmates get their degrees. The school had a rule that limited remote learning, so Curry couldn’t finish his degree while playing full NBA seasons, but during the 2011 lockout, he went back to campus and took classes.

When Davidson loosened remote-learning rules in the pandemic, Curry decided this was the year he would graduate, and there he was last spring, waking at 6:30 a.m. Pacific Time to Zoom with professors and having tutors visit him at home. Ayesha says they would FaceTime during Warriors road trips, and Steph was working on his thesis. He was like a college kid playing in the NCAA tournament—studying, traveling and trying to win a championship. All along, he could have received an honorary degree, but he had no interest. McKillop used to tell his players, “Finish everything,” and Curry was listening. Basketball’s most exceptional shooter wanted no exceptions.

In the early days of the NBA, stars were just players, and then they were celebrities, and then they became pitchmen. Today’s stars are conglomerates. In September, Curry assembled all of his people in Las Vegas for a retreat, and when he got there, he looked out at them and thought, Holy s---.

There were more than 50 employees there, working for various entities: SC30, his branding company; Unanimous Media; Underrated, his events company; and the Eat. Learn. Play. Foundation. That didn’t even count people who work for Ayesha’s company, AC Brands.

Many stars of this caliber, surrounded by so many others who are beholden to them, live in diamond-encrusted echo chambers. Myers says, “A lot of people in that type of stratosphere of fame lose the ability to even ask questions of other people.” When Curry’s employees all went to Topgolf in Vegas, he spent most of his time there teaching the game.

Curry got some publicity for helping fund the golf teams at Howard, but its director of golf, Sam Puryear, says, “It’s not about [credit for] the money with him. He has a vested interest in these young people. If I’m being honest with you, if it were up to him, he wouldn’t get any of the headlines. He’s that kind of guy.”

Curry texts with Puryear regularly. Sometimes he FaceTimes with Howard teams after events. When Howard played at Stanford in March, Curry—out of the Warriors’ lineup because of an injured foot—came to watch and to give the Curry touch. He spoke to the team, of course, but Puryear says, “It’s not so much what he said. He spent time with them.”

This summer Curry returned from a France vacation with Ayesha and arrived at the Olympic Hotel for his basketball camp the next morning. Brown, his high school coach, wondered whether Curry was tired from jet lag. Curry said, “Coach, it’s camp time. We’re ready to go.” He went to every session of the three-day camp, which is coed at his insistence and includes a financial literacy class. He let the kids watch him work out, so they could see what it takes to play in the NBA.

The Currys have also spearheaded the rebuilding of playgrounds in the Oakland Unified School District. John Sasaki, the district’s communications director, says the Currys are “a driving factor in transforming so much of our student experience.” Steph’s charity work, like his profession, brings him joy.

“I think he puts his head on the pillow every night and goes, ‘Man, what a great day,’ ” Kerr says. “He’s living such a full life.” Indeed, Steph is the kind of elite sleeper who leaves a spouse in awe: “I wish I could sleep half as well as he does,” Ayesha says. “His REM score is probably off the charts.”

McKillop teases Curry about running for office someday, but Ayesha says she can’t imagine that, “because I know that he doesn’t want to.” With his not-about-me manner and perpetual need to see the best in those who disagree with him, Curry is not a politician. He is what people want politicians to be. His charity work is mostly an attempt to give people the same kind of life that he enjoys. Eat well. Be financially secure. Play golf. Vote. Make your shots. Finish everything. Ayesha says, “Growing up and experiencing these things, he wants to share it with the community.”

This is what Steph Curry did this year: He moved forward in his game’s pantheon, went backward to get his degree and somehow stayed the same. He loved being on stage but also enjoyed walking off it. He gave people a good experience. Four championships, one Finals MVP, the all-time record for three-pointers, a burgeoning business empire, SI’s Sportsperson of the Year, and we know what Steph Curry is gonna say now:

How are you?