Jeff and Stan Van Gundy’s Long, Strange Journey to Your TV Screen

More than any other man on TV, Jeff Van Gundy exudes a raw punctuality. In 16 years traveling North America to call NBA games on ABC and ESPN, he’s never missed a flight, arriving at the airport two hours before departure like a character in a Progressive don’t-become-your-parents ad. “Those commercials are brilliant, because you see yourself in them,” he says. “Like the guy who’s trying to get the line straightened out?” That’s Jeff, wanting to tighten up the boarding queue.

His older brother, Stan Van Gundy, who calls games on TNT and NBA TV, also leaves for the airport several hours in advance. “What if there’s an accident on the way there?” he asks, unmoved by the mockery of his wife, Kim, who said at 7 on a recent morning: “I’m surprised you’re still here.” Stan’s flight was at 1 that afternoon.

The parents whom the brothers are becoming, Bill and Cindy Van Gundy, live near Stan in Florida. After watching her two children ham-and-egg national broadcasts four days a week through the first months of the season Cindy told Jeff, point-blank: “I can’t stand one more night of listening to a Van Gundy.”

Stan doesn’t blame his mother for feeling that way and strikes a note of apology when he says of the 90 or so two-hour appearances he and Jeff will make this season on your flat screen, tablet or smartphone: “It is more of us than NBA fans deserve.”

There have been days, in their vagabond basketball lives, when a Van Gundy has woken up in some blackout-curtained hotel room wondering where the hell he is. On a Wednesday in February, Stan, 63, was in Milwaukee, the morning after a Bucks game, waiting for a car to Chicago, to call a Bulls game, after which he’d fly to Orlando, where he and Kim, parents of four grown children, live with three dogs, five cats and a horse.

Jeff, 61, lives in Houston with his wife, also named Kim, and the younger of their two daughters, as well as two cats that are “not mine,” but he’ll be on the road continuously during the NBA’s conference finals and Finals. Wherever they are, the brothers find themselves wondering: How did we get here?

“The story is an incredible one,” Stan acknowledges of their 30 unlikely years at the pinnacle of professional basketball, and it starts in the summer of 1977, with the Van Gundy brothers—for the last time in their lives—running late.

It was after midnight, near the end of that long-ago August, when 18-year-old Stan entered his parents’ bedroom in the East Bay and told them he was no longer enrolling as a freshman at UC Davis and would instead join his family across America, in upstate New York, where Bill, who had been the interim men’s basketball coach at Cabrillo College, had agreed to become the new head coach at SUNY Brockport. It wasn’t Dad who changed Stan’s mind. “I changed my mind because I didn’t want to be 3,000 miles away from Jeff,” says Stan, whose little brother was 15 years old. “Jeff was my best friend.”

Jeff and Stan are each other’s only siblings. Forty-five summers ago, the two of them raced across the continent to get Stan enrolled at Brockport. Bill and Cindy would come later, in the family’s other car, but that week, the teenage brothers were on their own, at large in America. As the theme song to that summer’s hit movie, Smokey and the Bandit, put it, they were “Eastbound and Down,” with “a long way to go and a short time to get there.”

Stan and Jeff had four days to get from Martinez, Calif., to upstate New York in the family’s tiny Datsun with only each other and the radio for company. “I remember getting a ticket somewhere in Nebraska,” Stan says. “They pulled over 15 cars, and we had to follow this guy into downtown and drop our check in the mailbox before they’d let us go.”

East of there, in the great middle of America, Stan became ill. But the brothers still had to make time, so Stan closed his eyes, reclined his head and let his little brother take the wheel. Jeff was unlicensed and never switched seats with Stan on that razor-straight stretch of highway. “Stan kept his foot on the gas, but I was driving from the passenger seat,” says Jeff, sitting in his house in Houston, marveling from a four-decade remove at what sounds like a lost scene from Dumb and Dumber. He contemplates the horror of his own children pulling such a stunt. “But back then?” he says. “Everything was O.K.”

Indeed, Stan and Jeff are still here—wherever here is—still traveling the country, still two halves of one creature, copilots at the wheel of a sleek moving vehicle: the NBA. They are perhaps the most prominent analysts breaking down league games on national TV. If you’re watching an NBA game from opening night to Game 7 of the Finals, chances are one Van Gundy or the other will be the voice you hear.

Stan, former coach of the Heat, Magic, Pistons and Pelicans, calls regular-season games on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Jeff, former coach of the Knicks and Rockets, has Wednesdays and Fridays, as well as some Saturdays and Sundays. The Brothers Van Gundy are idle Monday, except late in the season and during the playoffs, when you might encounter them at any time.

If you listen closely, you’ll hear them conversing across separate networks, across different nights. When Jeff says on ESPN that pickleball isn’t a viable television sport—though he loves cornhole—Stan replies a night later on TNT that he’ll watch golfers play golf on TV, but he won’t watch football players play golf on TV. Jeff frequently violates the improv comedy principle of “Yes, and,” in which a good partner agrees with and expands upon the premise given to him. After the Sixers’ 7-footer, Joel Embiid, took it coast to coast and then got whistled for traveling in a game in February, Jeff’s play-by-play partner, Mike Breen, said, “It’s pretty amazing watching a guy his size dribble it up the floor at that pace.”

Jeff: “Yeah, that’s really electric to watch him double dribble.”

After a second of silence, Jeff’s co-analyst, Mark Jackson, asked no one in particular: “What’s wrong with this guy?”

What’s wrong with him is precisely what’s right with him. “Every game, Jeff teaches you something,” says Breen, who has known Jeff for 30 years. “Every game he makes you laugh. And every game he makes you say, What?”

When a pop star walked past the announcers’ table on the way to her courtside seat at Golden State during Game 1 of the 2017 NBA Finals, Jeff ignored LeBron James’s dunk on Warriors reserve JaVale McGee and instead shouted on the air: “Rihanna just walked in front of me! Are you kidding me?!”

A connoisseur of stand-up comedy, Jeff was preoccupied throughout a game in Los Angeles after spotting comedian Bill Burr in the seats. He was giddy over the proximity of Jennifer Garner eating breakfast at a hotel in Santa Monica. “Jeff gets excited when he sees celebrities,” says Breen. “He went crazy seeing Justin Bieber at a Dallas Mavericks game.” The Biebs fancies himself a baller, but Jeff’s overriding thought standing next to the pop idol was: I could post this kid up.

Jeff is less easily impressed by the celebrities who play professional basketball. “Do you want more NBA action?” his sometimes partner Dave Pasch asked on an ESPN broadcast this season while promoting the league’s app. There followed a brief interval of silence, after which Jeff replied to the rhetorical question: “I thought you were asking me if I want more NBA action. I didn’t realize you were reading a promo. And the answer, if you wanna hear it, is: It depends who’s playing.”

On the continuum of TV brothers, Jeff and Stan are worthy successors to Hoss and Little Joe, Wally and the Beave, Frasier and Niles or Phineas and Ferb. Unlike all of them, the Van Gundys never appear together, though their game schedule did overlap once last season, in New York City, where they met for a meal. But over lunch and over the air, Jeff and Stan are still in that Datsun, talking to each other on some lonely road.

In the second half of a game in Los Angeles, hungry Stan salivates over the Burger King ad read on TNT as if it’s a passing billboard. (“Getting a little hangry,” says his play-by-play partner, Brian Anderson, as Stan complains of these late-game food teases.) Two days later on ABC, hungry Jeff salivates over B-roll footage of shellfish. (“Joe’s Stone Crab,” he says, the way Homer Simpson might say “doughnuts.”)

Stan is adept at surgically deploying statistics in a way that captures that night’s matchups, while Jeff is fonder of esoterica. When calling a Celtics game this winter, Jeff wondered out loud how many other NBA players or coaches in history—like Boston coach Joe Mazzulla—have had consecutive Z’s in their name.

Five days later, Jeff’s phone was still pinging with texts from Bill Walton: Walt Hazzard . . . Cazzie Russell . . . Buzz Peterson . . .

These are the contrasting styles of the Brothers Van Gundy. An NBA ref told Stan: “During games you [were] a wack job as a coach, and as an announcer you’re completely rational. And your brother, as a coach, was completely reasonable but as an announcer is a complete wack job.”

Stan and Jeff first faced each other as head coaches on Nov. 11, 2003, in Houston. Jeff had future Hall of Famer Yao Ming; Stan had future Hall of Famer Dwyane Wade. From opposite sides of the Toyota Center scorers’ table, for a single fraught second, the brothers held each other’s gaze. Jeff briefly became not verklempt, exactly, but self-conscious. “I remember looking down at Stan—and I’m not overly sentimental or anything—but I’m like: Man, two Division III schmucks are staring at each other.”

Before they were on this side of the TV, they were on the other. Stan was the better player but allowed Jeff to tag along to pickup games on Sunday afternoons, after the brothers had watched a 10 a.m. Pacific time tip-off from some smoke-shrouded theater of dreams back East.

In the bottle-green glass of a Zenith console, they saw their own future selves reflected back. Jeff’s favorite show was Hawaii Five-O. It had the best theme song, a superlative catchphrase—“Book ’em, Danno”—and Detective Captain Steve McGarrett, his crest of hair breaking like a big wave on Banzai Pipeline. “The only thing I could never figure out was why McGarrett always put Chin Ho on the tail [of suspects],” says Jeff. “Chin Ho lost every tail ever, and I just couldn’t understand why he was given so many opportunities. That was always confounding to me.” As an 8-year-old, Jeff was already breaking down film and thinking of adjustments.

Stan loved sitcoms. But even his favorite show, M*A*S*H—the most socially conscious comedy of its era—was missing something, though he didn’t know that as a child. “The lack of diversity on TV at the time was just incredible,” Stan says now. “But my eyes were just not open to it.”

Basketball opened his eyes. He was a Heat assistant with Bob McAdoo, who attended segregated schools for most of his primary education. “This isn’t ancient history,” says Stan, noting that McAdoo is only eight years older than he is. “That’s why I sort of laugh when people like me get criticized on Twitter and in my state—Florida—for being quote woke. I’m not sure what they mean by that, or why it’s a negative that you would try to be awakened to some things that are going on. I sort of kick myself that I was asleep for as long as I was. And I’m still not awake to most of the inequities in our society.”

On Twitter, where Stan has lamented book banning, election denial, corporate malfeasance and a general slouch toward authoritarianism, he posted a simple rule to live by: “Just be kind to people and let them live their lives as they want as long as they do nothing to harm anyone else. Bigotry makes no sense. Why do you care how anyone else identifies? Respect their choice. Just be a decent human being.”

As a decent human being, Stan assaulted his little brother only one time, when they were teenagers. “I was irritating him,” Jeff concedes. “Stan was driving me home, and as he was driving he was just punching the s--- out of me. And if you know how bad a driver Stan is, you have to wonder: That car stayed on the road how?”

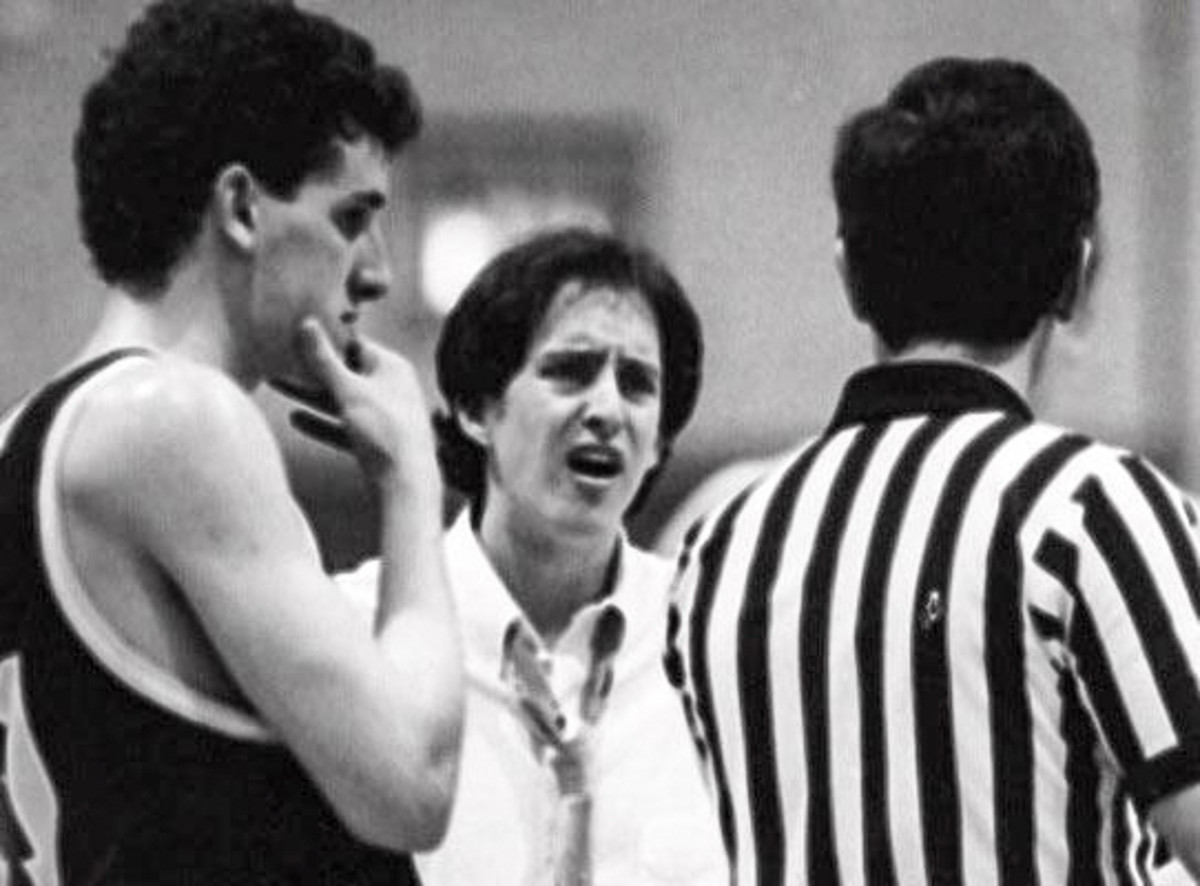

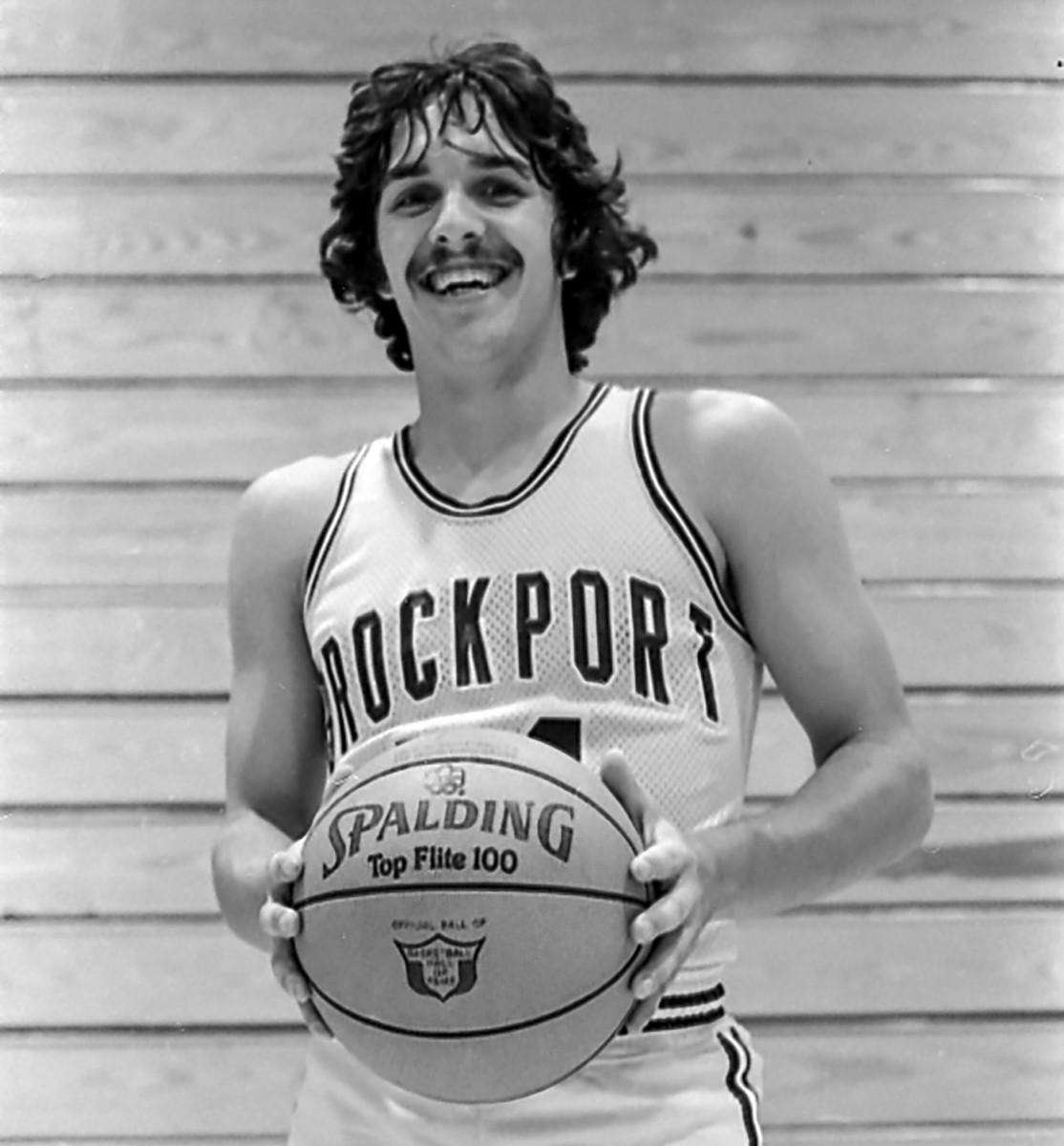

Soon after, they drove across country—Stan’s foot on the gas, Jeff’s hands on the wheel—into college basketball oblivion. As a guard at Brockport, Stan was all ’stache, tube socks and work ethic. Cerebral and relentless, “Stan was not athletic in any way,” his college coach and father memorably told NBA.com when Stan was hired to coach the Pelicans in 2020.

Jeff, by his own account, got into Yale with the lowest SAT score in the school’s 322-year history. “And Yale got no benefit,” he says. “I’m the only guy ever to go from Yale to juco over playing time.” After one Ivy season, Jeff transferred to Menlo (Calif.) Junior College, before moving on to Brockport and eventually Nazareth College. When Pacers point guard T.J. McConnell dapped him up at the broadcast table before checking into a game in Washington earlier this season, Jeff took it as a fellow point guard paying tribute. “He saw my game at Nazareth,” Jeff says. “I’m sure he studied it: me to Jumbo Cummings.”

“Twenty-some years later we’re staring at each other as head coaches and then 20 more years later, we have this alternative career that we never actually studied for,” Jeff says. “All I can think is, no two guys could ever be luckier.”

“We are two lucky SOBs,” agrees Stan, who can tell you the pivot on which both their lives turned. It began with Jeff’s meticulous preparation as the first-year coach at McQuaid Jesuit High in Rochester, N.Y. One afternoon in the spring of 1986, Jeff was working out his star sophomore, Greg Woodard, for Providence assistant Stu Jackson. Jackson came away impressed by the kid and his coach. He called his boss, Rick Pitino, and said, “Yeah, Greg Woodard’s a good player, but I got the guy we should hire as a grad assistant.”

“Boom,” says Stan. “Jeff goes to Providence, and he’s on the staff with Stu.” Pitino leaves Providence to coach the Knicks and brings Jackson. Jackson succeeds Pitino as Knicks coach and brings Jeff. Jeff stays on under Jackson’s successors, John MacLeod and Pat Riley, and when Riley leaves for Miami—and is denied permission to bring Jeff with him as an assistant—the younger Van Gundy tells the new Heat coach: “You should talk to my brother.” And so Pat Riley hires the Next Van Gundy Up.

“I had just been fired at Wisconsin,” says Stan. “That’s how I got in. And it all goes from there.” And so Jeff’s one season at a high school in Rochester was his only experience as a head coach before becoming head coach of the Knicks. “If not for Greg Woodard at McQuaid Jesuit High School and that workout, Jeff and I are probably both coaching small colleges somewhere,” says Stan. “And to be quite honest, we’d be happy doing that.”

Happy? Bill Van Gundy coached for 42 fulfilling years. His father fled the Dust Bowl for California with $20 in his pocket and eventually opened a gas station. By the time Jeff and Stan made the reverse trip, in the Datsun, the brothers were comparatively comfortable. “I wasn’t born on third base,” Jeff says. “I was born with my foot inches above home plate.” Bill and Cindy modeled a work ethic and sense of integrity that the brothers would come to appreciate as adults, when they realized what the Progressive commercials ignore: Some people are blessed to become their parents.

That’s because the brothers love basketball in a way that is perhaps unhealthy. Stan says he is a better human being when he’s not coaching. As for Jeff: “I’ve always said there’s no greater five minutes in life than the five minutes in the locker room after a great road win,” he says. “And people would always jump up: ‘What about the birth of your kids?’ And I’m like . . .” Here, Jeff winces, places his palms up and pantomimes weighing two objects. “Ehhhh.”

“I know, politically, I’m supposed to say, ‘Yeah,’ ” Jeff says. “But I tell you what: the first five minutes after a great road win? There is nothing better than those five minutes.”

Indeed, after stealing wins on the road, his Rockets stole the furniture. They would take a logoed folding chair from the visiting locker room as a trophy from their travels. Rockets point guard Charlie Ward inspired the nationwide crime spree, because his football teams at Florida State—where Ward won the Heisman Trophy in 1993—tore a piece of sod from the field after road wins and transplanted it at their practice field.

“I can’t believe their equipment guys never got arrested for that,” Stan says, but the Rockets’ equipment guy nearly did—in Chicago, while spiriting an upholstered Bulls chair into the cargo hold of the team bus. Word had gotten out around the league, and the minutes after every Rockets road win had turned into Ocean’s Eleven.

Jeff never liberated a chair from Stan, whose name is a slang synonym for obsessive fandom. Even Stan knows that. Otherwise, he’s not exactly a walking Urban Dictionary. That’s part of his charm. In January, Stan tweeted: “90’s NBA teams had just a trainer and a strength coach, they practiced more often and harder and played more back to backs. Teams now have huge medical & ‘performance’ staffs and value rest over practice. Yet injuries and games missed are way up. Something’s not working!”

To which one of Stan’s stans, the injured star Kevin Durant, replied: “Stan spittin…”

Stan didn’t realize that this was shorthand for spittin’ facts, and so he replied to Durant: “No, I’m not criticizing players. I’m saying that we are getting something wrong in how we prepare and train players . . .”

“Stan, I agree with u,” Durant typed back. “lol.”

That night on TNT, Stan said: “My defense is I’m old. Really, really old.”

Several weeks later, reflecting on the exchange, Stan said: “I was more up on the trends when my kids were at home. But with them all out of the house? I have no idea what’s going on.”

As any parent knows, the kids are home for only a short while before they leave the nest and embark on their own futile quests to avoid becoming their parents. “Some days you got all these kids in different activities running in different directions and you say, ‘God, can we just get a day off?’ ” says Stan, whose youngest, Kelly, is in grad school. “And now? I’d give anything to be back in those days.”

After getting fired by the Rockets after the 2006–07 season, Jeff got out of NBA coaching entirely because—as he said at the time—he really did want to spend more time with his young family. “I think everybody should be able to slow down when their kids are growing and work after,” he says. “It was a blessing because I was around my older daughter [27-year-old Mattie] a lot more. And my younger one [19-year-old Grayson], I was around all the time. She thinks I’m a hovering parent. I’m the worst.”

The only comforts he misses from the full-time circus life of the NBA are what he calls The Three C’s of Coaching: “competition, camaraderie and charters.” It’s the third C that haunts him on the road this spring as he calls the NBA playoffs and Finals. One of the great disappointments of Jeff’s life was being stripped of his Global Services status on United, the airline’s invitation-only, frequent-flyer Shangri-La, for insufficient mileage. After that dark day, Jeff admits he pouted for three weeks. (“Three weeks?” says Breen. “It was longer than that.”)

Stan is still addressed on air as “Coach,” but not because he flies it. His frequent play-by-play partner, Anderson, calls him “The King of the Mint Section,” a reference to the lie-flat enclave on JetBlue. Despite the priority-boarding consolations of first class, Stan schleps to the airport before dawn the morning after games, like his brother, to get the earliest flight home. “I was proud of myself,” Stan said on a recent day, after arriving at his gate just 30 minutes before departure. He’s cutting it closer and closer. When Anderson asked him this season whether he’d already turned in his postseason awards ballot, Stan scoffed: “That would be a little early. I probably won’t get to that until next week.” It was Jan. 12.

I’m a clown,” Jeff insists of his broadcasting role, eager to ignore the fact that he’s a multi-keyed custodian of the game, with a platonic ideal of how basketball can and should be played, all of which begins with maximum effort. “People talk about, ‘What are your team defensive principles?’ ” he says. “How about trying? Run back.” He’s a Ph.D.-level strategist but boils the game down to its essence: “The biggest adjustment you can make is to play a lot harder. Everybody wants to make it strategic.” A team-first attitude helps. “I guarantee if you take a Lopez on your team, your positivity goes up,” he says of the twin big men Brook and Robin Lopez, a set of slightly less prominent NBA brothers.

That league listens to Jeff. Breen is convinced the NBA cracked down on flopping in large part because Jeff constantly called it out on the air. Breen, the play-by-play voice of the NBA Finals for 17 years, says of Jeff: “He’s so damn smart but never acts like he’s the smartest guy in the room. I really believe he is one of the finest analysts ever to do television.”

Mark Jackson, a boxing fan, cites the ring maxim that “styles make fights,” and Jeff replies that the same is true of the NBA. “When I was with the Knicks, you had the Pacers running a lot of baseline screens for Reggie Miller and posting Rik Smits,” Jeff says. “Then you’d play the Bulls and get the Triangle. Go down and play the Heat and you’d have the Alonzo Mourning–and–Tim Hardaway pick-and-roll. There were just more different styles that I found—for me, as a coach and fan—more enjoyable. Today the skill level is off the charts. These guys are great. But many of the games look very much the same: high pick-and-roll and isolations.”

Jeff thinks the NBA could become instantly more interesting with a single brushstroke: “I would love to eliminate the corner three,” he says. “I don’t understand why for a shorter shot you get the same point value. It would also eliminate two guys just standing in the corners.” His other peeve would fit neatly into a Progressive commercial: “The uniforms drive me crazy. Home teams should have to wear white.”

Stan sees another existential crisis for the league. Load management—the euphemism for leaving stars out of the lineup—screws fans and devalues the regular season. “Without the fans we have no league,” Stan says. “What we have then is AAU basketball: Put together a lot of talented people and let them play, and nobody’s watching.”

A more gratifying league trend is coaches in quarter-zips. Once swaddled in designer suits—Stan sat next to Armani mannequin Pat Riley on the Heat bench—NBA coaches now look like they’re pushing a cart through the produce aisle at Kroger. “I absolutely love it,” says Stan, who sighs that he had one year of coaching in quarter-zips, in New Orleans in 2020–21, and now that he’s broadcasting, he’s back in a coat and tie.

Twenty years ago, in the Champions sports bar in the Atlanta Marriott Marquis, Jeff sat alone at a high-top table watching Stan coach the Heat in Miami. Jeff’s Rockets would play the Hawks the next night, but for now he was absorbed in his big brother’s game on TV. Late in that close contest, Jeff leaped from his barstool and made a T with both hands, demanding a timeout for his brother from 660 miles away. And then Jeff tapped his own shoulders, changing from a full to a 20-second timeout.

When the game was over and Jeff was on his way out of the bar, two guys—the only other patrons of the joint—stopped him to say that his long-distance coaching looked like a sweet act of brotherly love. “What are you talking about?” Jeff said, genuinely perplexed. He’d been absorbed in the game, unaware of what he’d been doing, which essentially was this: steering from the shotgun seat for his brother in need.

Stan does the same for Jeff. In March, he and Kim, along with Bill and Cindy, flew to Houston to see senior Grayson Van Gundy perform in her final high school production. For the last two performances of three-day run of Mamma Mia!, her dad had to be in Los Angeles to call a game.

It’s that time of year when Jeff will start living out of a suitcase. Lord knows there’s room in it. As a coach, he packed only one suit for five-game road trips. To gird himself for the grueling postseason road ahead, Jeff is getting his steps in, striving for a net-zero health equilibrium by walking the treadmill while eating M&M’s.

Stan prefers to walk outdoors, though Jeff suspects his brother is strolling “while eating Chips Ahoy!” On hearing this, Stan laughs his wonderful laugh, like a car engine wheezing to a start on a cold winter morning. Is the allegation true? Stan’s laugh goes on for five full seconds, until he finally says of his brother and best friend: “He knows me well. He knows me well.”