Carmelo Anthony Is at Peace With His Retirement

This time, Carmelo Anthony is at peace.

That wasn’t the case the first time he contemplated the end of his career, back in November 2018. After a bizarre, head-scratching stint with the Rockets that ended when the team unceremoniously cast him off 10 games into the season, Anthony was forced to confront life without basketball. “I ended up being away from the game for [a year], and that time showed me, Oh, this is what [the end] feels like? Nah, I’m not ready yet,” Anthony says during a car ride on a May afternoon from midtown Manhattan to his childhood neighborhood of Red Hook, Brooklyn. “I knew I still had something to give—that I could help a team if I just got another opportunity.”

It took a year for him to get that chance, but the Trail Blazers came calling early in the 2019–20 season, offering Anthony the shot at basketball redemption he so desperately craved. Things went so well with Portland that the club signed Anthony back for a second season, during which he shot a career-best 40.9% from three-point range. Then the Lakers reached out to Anthony in the summer of ’21 to offer him a bench role at age 37, for his 19th professional season.

Anthony’s rock-bottom moment following the Houston situation gave him a Scrooge-like perspective. By experiencing what, to him, felt like a firing from the Rockets, Anthony went through a form of basketball death. “It was this roller coaster of not knowing what comes next,” he says. “Ups and downs. Mentally, spiritually, emotionally. On and off the court.”

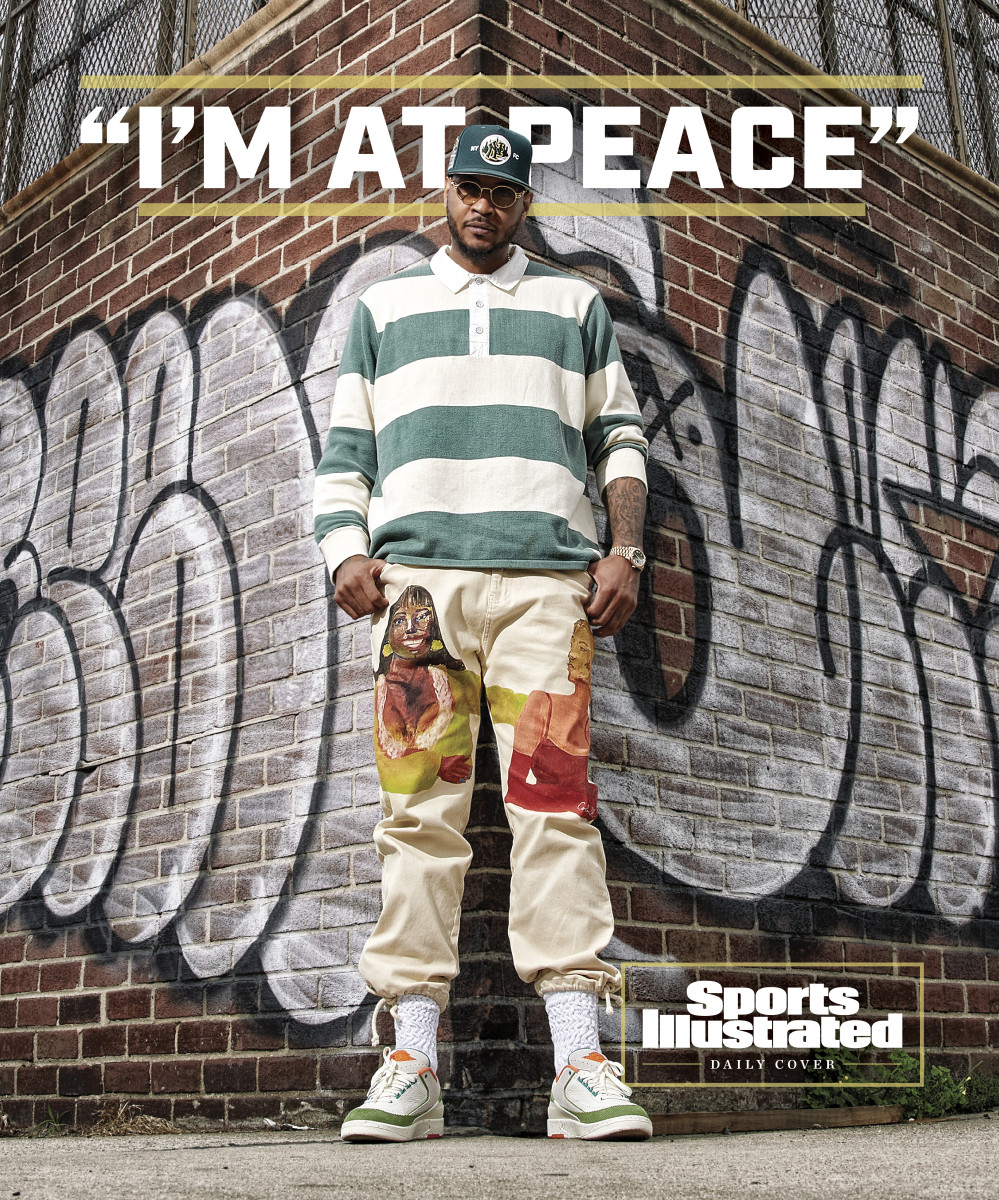

Yet going through it readied him for the decision to retire now. “It’s weird to use the word happy, but I’m happy,” he says, wearing a green-and-white, long-sleeve pullover, sunglasses and green baseball cap that covers his braids. “It took a lot for me to get to that point, and to be able to see it all clearly. But I do.”

Anthony, who turns 39 on May 29, walks away from the sport having scored 28,289 points, the ninth most in NBA history. He was a load for defenders to deal with: an elite, three-level battering ram whom Kobe Bryant, Paul Pierce and Paul George all said was the toughest player to guard. He was famous before setting foot in the NBA, having led Syracuse to a national title in 2003 as a true freshman. Upon being drafted No. 3 later that year by Denver—which hadn’t reached the playoffs in eight years—the forward changed the trajectory of the franchise. The Nuggets earned postseason berths for 10 consecutive years after the Carmelo pick, including a trip to the Western Conference finals against Bryant and the Lakers in ’09.

Despite having led the NBA in scoring and having finished third in MVP voting in 2013, despite having made the All-NBA team six times, despite having been a 10-time All-Star and a four-time Olympian (with three gold medals), Anthony understands he leaves the game with a label. Of the top five players taken in the historic ’03 draft class—four of that quintet will end up in the Hall of Fame—he’s the only one without a ring. In fact, only one player in NBA history has scored more career points in the regular season and playoffs combined without winning a championship: Karl Malone.

“I’m at peace. That doesn’t bother me no more; that idea that you’re a loser if you don’t win a championship,” he says. “For me, I’ve won. I won back in 2003, the night I shook David Stern’s hand on that [draft] stage. I made it out of Red Hook. I’ve won at life. The ring is the only thing I didn’t get. It would’ve been a great accomplishment, but I don’t regret it, because I feel like I did everything I could to get it.”

There were moments in his career that easily could have flipped the script. During the summer of 2006, while he was training with fellow Team USA players and draft class members LeBron James, Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh, Anthony chose to sign a five-year, $80 million maximum extension with the Nuggets, a choice that ran counter to the shorter, three-year deals those players were signing so they could later all test free agency simultaneously. “My memory of that is that I called Mel like right as he was sitting down to sign his deal,” Wade says, “and by then, it was too late.”

Anthony remembers it similarly, and says he now wishes he’d considered the upside of agreeing to a shorter deal at the time. “The only regret I’ve got there is not being intelligent enough about the business of the game,” he says. “I got that call from [Dwyane] saying, ‘Take the three-year deal; we’re all doing that,’ and I’m like, ‘Do you know where I’m from, man?’ Like, I’m happy, bro. I’m cool with Denver.’ ”

Of course, James, Wade and Bosh joined forces in Miami during the summer of 2010. They made four straight trips to the NBA Finals together and won two championships.

The following season, Anthony requested a trade out of Denver, citing several key Nuggets players’ contracts expiring, and landed back in his birthplace: the Knicks acquired him in a February 2011 blockbuster that saw New York hand over a third of its roster and three draft picks to Denver. Even with fellow star Amar’e Stoudemire unavailable for long stretches due to knee injuries, Anthony led the Knicks to 54 wins and the East’s No. 2 seed in ’13. He also led the NBA in scoring, and New York set a league record at the time for threes made in a season.

But with Anthony playing for five different coaches over his seven-year stretch in the Big Apple, that 2012–13 campaign ended up being the high point of his tenure. Hall of Fame coach Phil Jackson was brought in to serve as the club’s president in ’14, just months before Anthony was set to become a free agent for the first time. In Anthony’s view, things got awkward quickly, because Jackson publicly suggested he take a less-than-max contract as a way of helping the team—something that prompted Anthony to question how much Jackson truly wanted him to remain a Knick in the first place.

“I’m thinking, Is this really happening? That’s the energy?” Anthony says, recalling that he almost agreed to terms that summer with the Bulls, who had 2011 MVP Derrick Rose, ’14 Defensive Player of the Year Joakim Noah and eventual All-NBA wing Jimmy Butler on the roster. “And even after that, I still made the choice to come back. I just wanted to feel like we were in it together. But that never happened. The energy was shifting [with Jackson], and I understood that later. But I told myself: I’m not breaking. I’m not folding. New York is where I wanna be.”

Anthony ended up outlasting Jackson—who was fired after failing to get the Knicks to the playoffs in three-plus years—by a few months before agreeing to waive his no-trade clause to head to Oklahoma City in 2017. But the reality of Anthony’s career is that the sport shifted underneath his feet during his career. At the front end of Anthony’s run, volume shooters like him and Allen Iverson—a teammate of Anthony’s in Denver—were highly coveted, in part because of their willingness to take and hit highly contested looks.

As the game grew more analytical, with switchy three-and-D wing players valued at a premium and some teams actively avoiding the midrange portion of the floor at all costs, Anthony’s style became more polarizing and then fully fell out of favor as he exited his prime and finished his time with the Knicks. In a matter of years, he went from being able to dictate what market he wanted to go to via trade to having to answer questions about what sort of role he would be willing to accept. Would he be willing to come off the bench? (He was less open to this possibility right after his time in New York, but eventually did it.) Could he play off the ball rather than dominating it through isolations? Could he devote himself on defense, and play power forward more frequently? (“I fought playing the four at the beginning, because I wasn’t ready to make that transition,” he says. “It’s a lot [physically] having to guard a Z-Bo or a Gasol. Big adjustment.”)

But eventually, Anthony says, he expressed a willingness to do whatever it took to merely fit in. That’s what confused him—what still confuses him—about what took place in Houston in 2018. Fresh off a campaign in which the James Harden– and Chris Paul–led Rockets fell one win shy of making the NBA Finals, Houston had high expectations. Anthony came off the bench for the first time in his career, posting unalarming if uneven numbers over his first 10 contests as a Rocket: 40.5% from the field and 32.8% from three while averaging 13.4 points and 5.4 rebounds. (He had three games of 22 points or more in that span.) The bigger problem, it seemed, was the lack of winning by the Rockets.

So after a 4–6 start to the year, then Rockets general manager Daryl Morey told Anthony the team was moving in a different direction. Anthony was floored. “Nobody ever really explained it to me,” he says. “To be honest, nobody can explain it to me, because there’s no real reason as to why any of that transpired. And I beat myself up about it. I took the role off the bench. I did everything they said I gotta do. So I kept thinking, It’s gotta be deeper than that. It felt like it was about more than just basketball at that point.”

Portland ended up being a saving grace for Anthony, who was in turmoil both personally—his 11-year marriage to La La Anthony was ending—and professionally. In the Blazers, Anthony found a small market and eager fan base happy to have him, something that did wonders for his confidence and helped restore his expletive-filled swagger. Game-changing defensive stops and game-winning shots helped, too. “With where they were and where I was, it was literally perfect. Easy. No pressure. I was at peace again,” Anthony says. “Hindsight is 20/20, but I wish I could’ve gone there even sooner than I did.”

That’s not the only aspect of his career that Anthony has thoughts on. Standing near the Louis J. Valentino, Jr. Park and Pier in Red Hook, looking out at the Statue of Liberty, Anthony reflects. He feels he should have won Rookie of the Year in 2004—either over James, his longtime friend, or as a co-winner. He has a point: Anthony averaged 21.0 points, 6.1 rebounds and 2.8 assists in ’03–04, to James’s 20.9/5.5/5.9. “I should have won that; everybody knows,” Anthony says, laughing. “I thought we’d at least share it, since we both lived up to the expectations that first year. He had an incredible year, and in my case, we made the playoffs.”

J.R. Smith, who played alongside Anthony in Denver and New York, goes down as his favorite teammate. Asked about his favorite moments as a pro, he mentions two: the first time he was introduced to the Madison Square Garden crowd as a Knick back in 2011, and the incredible 43-point Easter game he had at MSG against the Bulls in ’12, when he hit contested game-tying and game-winning triples from the same spot on the right wing.

When asked whether he thinks of himself more of a Nugget or a Knick, Anthony says his game was in its purest form—and his team at its most competitive—during his time in Denver. “That version of me was more of a force,” he says. “I was hungry. Physical. Tough. It was a validation of where I came from, and how I played. As soon as I got to New York, it started to become more about, ‘He’s gotta change his game, and he’s gotta do this or that.’ … Between that, and the intelligence you had to have in dealing with New York and all the media stuff, it went beyond just having to perform on the court. New York felt like more of a survival stage, if that makes sense.”

Anthony won’t miss being tabloid fodder in New York. He alluded to the deluge of criticism that current Knicks star Julius Randle has gotten. “Now I can wake up and say, ‘Damn, [thank goodness] they ain’t talking about me!’ I can sit back and rest,” he says. “I felt it for all those years, but being on the other side of it, I have a different perspective now. I see what’s gotta happen from a media perspective, but I feel for the athletes.”

For all the focus on Anthony’s game and whether he truly enhanced his skill set over time, his biggest transformation came off the court. His first few years in the league were marked by incredible talent, but also by some PR missteps. After a 2006 fight at the Garden—which included Anthony throwing a sucker punch at New York guard Mardy Collins at the end of an altercation between the Nuggets and Knicks—then commissioner David Stern eviscerated Anthony during a meeting and suspended him for 15 games. “You wanna be in the streets, or you wanna be in the NBA?” Stern said to Anthony. “You’re f---ing with a corporation now. You’re gonna leave that stuff alone.”

Anthony eventually built an entire team of advisers around him to handle his affairs. And, following in the footsteps of his late father—an activist and member of the Young Lords, a group that works for equality, civil rights and Puerto Rican sovereignty—he began to add his voice to social justice efforts. He marched with protesters in the city of Baltimore in 2015 after the death of Freddie Gray, a Black man who suffered fatal injuries while police transported him—unsecured and unbuckled—in a van. In ’16, Anthony, James, Wade and Paul delivered a group speech on social activism and consciousness to open the ESPY Awards. That same year, Anthony hosted a town hall on community policing in Los Angeles, and communicated with Colin Kaepernick as the 49ers quarterback became one of the biggest stories in the country due to his decision to kneel during the national anthem as a way to protest police brutality.

So what comes next? Anthony doesn’t expect to stray too far from the game that has given him everything. “Basketball is what I always have my eyes on, and that’s why I wanted to have a better understanding of the business and sit on the [NBPA executive] committee—to sit across from the owners and understand how it all works,” he says. He owns Puerto Rico FC, a team in the North American Soccer League, and says he’s open to buying ownership stakes in other teams over time.

For now, he wants to pour more time into his 16-year-old son, Kiyan, a 6'4" sophomore who has already racked up 10 basketball scholarship offers, including one from Syracuse. “I always told him, ’When you get to high school, I’m retiring.’ That was always our thing,” he says. “Then [as he started high school] the Lakers called, and he told me, ‘Dad, I’ll be O.K.—you should go.’ Even with LeBron there, I wouldn’t have done it without Kiyan pushing me. So to be able to spend time with him in the gym, on his work ethic? With school? I can be a father to him every day. It’s perfect timing.”

And it’s why, after years of being a focal point in New York, he finally finds himself in perfect peace.