Phoenix Is the Rare NBA Team Still Embracing the Superteam Model

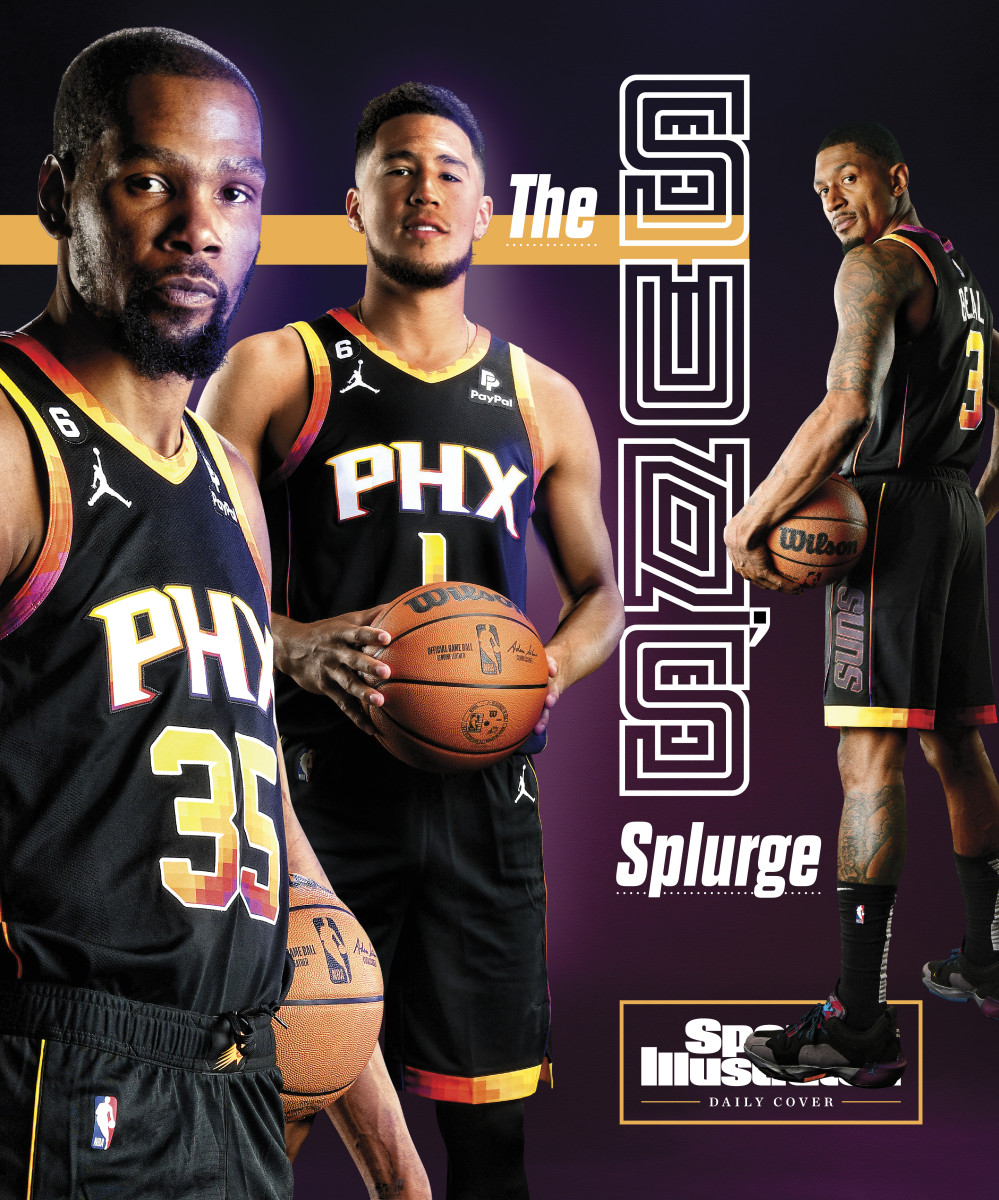

In mid-May, a few days after the Suns’ season ended and with the wounds from a second straight second-round playoff exit still fresh, Phoenix’s basketball brass—owner Mat Ishbia, CEO Josh Bartelstein and GM and president of basketball operations James Jones—gathered in a conference room at the team’s practice facility. The high from the midseason trade for Kevin Durant had long faded, replaced by the whiplash from a series-ending 25-point shellacking by Denver in Game 6 of the second round of the playoffs. But despite that disappointment, optimism remained. With Durant and shooting guard Devin Booker, Phoenix possessed two elite scorers. Over lukewarm coffee, the front office brainstormed about the right pieces to put around them.

Options were discussed. Shooters. Playmakers. Three-and-D wings. The Suns, already over the salary cap, had limited tools at their disposal. The mid-level exception. The biannual exception. Minimum salary deals. They could run everything back and hope that better health—the trio of Durant, Booker and point guard Chris Paul played 167 minutes together before the playoffs—would yield better results. Still, as the meeting progressed, one strategy earned consensus: If the opportunity arose to add another star, the team needed to be aggressive. “It just got us down the line of thinking about the game’s best players,” says Jones.. “And those guys that we could pursue that we thought could mesh well with Devin and Kevin.”

Weeks later, one star player did. It began with a phone call. Mark Bartelstein calls his son often, sometimes to commiserate over the White Sox. Or to see how Josh, who accepted the Suns job last April, is settling in. This call was different. Mark, the president of Priority Sports, represented Bradley Beal. The Wizards had just overhauled their front office. If Phoenix was interested in Beal, Mark suggested the Suns check in with them.

Phoenix didn’t have much to offer, asset-strapped as it was after the Durant trade. But Beal had a no-trade clause, and, after a face-to-face with Suns staff in New York, Beal saw Phoenix as his preferred destination. The assets the Suns surrendered for Beal, an All-NBA selection in 2020–21, were not an issue: the 38-year-old Paul, Landry Shamet, six second-round picks and four first-round pick swaps. The payroll cost, though, was significant. In Durant, Booker and Beal, the Suns would be allocating $130 million to three players. Also on the roster then was Deandre Ayton, who was owed $33 million, bringing the four-player total to $163 million. In Beal (owed $207 million over the next four seasons) and Durant ($153 million over the next three), Phoenix would be making long-term, cap-consuming commitments to two players over 30 with lengthy histories of injury.

Since acquiring controlling interest in the team last February, Ishbia had signed off on every deal, including the Durant trade, which added $40 million to the Suns’ luxury tax bill. Still, Jones wondered: Would Ishbia approve the Beal deal? “It was a big ask,” says Jones. But the conversation was brief. “It was, ‘Do you believe this will help us get closer to our goal of winning a championship?’ ” recalls Jones. “I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘O.K., well, let’s do it.’”

Says Ishbia, “No one’s going to remember how much money we lost or how much money we make. They remember how many championships you win. That’s what people care about. I’m not worried about money. Money follows success, not the other way around. Let’s go win. Let’s go have success. Let’s go do right by the fans. Money will follow.”

Free-spending owners, or, more specifically, new owners who spend freely, have a history in the NBA’s ecosystem. Soon after Mikhail Prokhorov took ownership of the Nets, the Russian oligarch racked up a then-record $80 million luxury tax bill in 2013. Steve Ballmer, the former Microsoft CEO who bought the Clippers in ’14, spent L.A. into the tax in his first season. As costs for NBA franchises have skyrocketed—Ishbia purchased controlling interest in the Suns and the WNBA’s Mercury from the embattled Robert Sarver at a valuation of $4 billion—so too have the number of deep-pocketed owners eager to splurge on them.

Still, the Suns’ spending spree is different, largely because it’s happening just as the NBA begins a stringent crackdown on them. The recently ratified collective bargaining agreement—a 676-page document that levels the field for the NBA’s cadre of small-market owners—amounts to a spending straitjacket. Along with escalating financial penalties (beginning in the 2025–26 season) teams spending deep into the tax—defined in the CBA as a “second apron,” a number $17.5 million above the league-set luxury tax threshold—will lose valuable roster-building tools. The mid-level exception? Gone. The ability to aggregate salary in a trade? Can’t do it. Future first-round picks? Frozen. So draconian are the NBA’s new rules that even the league’s heaviest taxpayers (the Warriors, the Clippers) spent the summer slashing payroll.

So why was Ishbia, in his first NBA offseason, bucking the trend? Why, when the rest of the NBA is zigging, are the Suns making an expensive zag? “Because we didn’t win last season,” says Ishbia. “And I don’t do anything to lose.”

It’s early August, and Ishbia is speaking over Zoom from his office in Detroit. He’s in business attire, fitting for a man who oversees a $16 billion company. After graduating from Michigan State—where the 5'10" Ishbia spent three seasons as a third-string point guard under Tom Izzo—he joined the family business, United Wholesale Mortgage, assuming full control of operations in 2013. At 43, Ishbia’s net worth is estimated at $6.9 billion, which helps explain why he’s willing to swim in red ink for a while.

“We believe this is the best way to put ourselves in position to win a championship,” says Ishbia. “That’s the focus. That’s the only focus.”

Spend enough time with Ishbia and you start to believe him. He speaks with blurring speed and unwavering conviction. The decision to replace Monty Williams two years after a trip to the Finals? “He wasn’t the guy that we believed was going to take us to the place we wanted to go,” says Ishbia. The suggestion that the skills of the Suns’ three volume scorers overlap? “I think we’d rather score more than less,” he deadpans. The popular argument that burning cap flexibility on stars will leave Phoenix’s roster too top-heavy to compete for a championship? “The second apron creates hurdles,” says Ishbia. “But you have got to measure how big that obstacle is versus Brad Beal, Devin Booker [and] Kevin Durant. Where would I rather go? I’m going to go this way. I’m going to go all in.”

Ambitious, yes. Prudent? Superteams, in one form or another, have defined the modern NBA. But for every Miami Heat, which won two titles in the four years LeBron James, Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh played together, there is a Los Angeles Lakers team with Kobe Bryant, Dwight Howard and Steve Nash that was swept in the first round in their lone season together. The Clippers spent $331 million in payroll plus luxury tax last season on a team that didn’t get out of the first round.

Denver, the reigning champion, is the anti-superteam, with one superstar (Nikola Jokić) and a deep, versatile supporting cast that has spent years together.

Presented with that argument, Ishbia shrugs. “I think it’s funny that people think, ‘Oh, having three great players doesn’t work,’” says Ishbia. “I believe with a hundred percent of my heart that this is going to work.”

In the spring of 2016, some NBA officials believed the league was trending toward a long-desired goal: parity. Superteams, while compelling and often good for a Finals ratings boost, were antithetical to the NBA’s desire for competitive balance. And while Golden State won 73 games in ’15–16, and the James-led Cavaliers stormed through the Eastern Conference playoffs, there were signs that the playing field was leveling: Oklahoma City nearly ousted the Warriors in the conference finals, the Kawhi Leonard–led Spurs were coming and Toronto, a 56-win team, looked like a worthy foe. The collective bargaining agreement, which created the first luxury tax threshold, was working.

Then came the summer, the spike (the term used to describe the TV cash infusion that pushed the salary cap up 32%, creating the room needed for Golden State to sign Durant) and the emergence of a new superpower. The Warriors, already formidable, won two of the next three championships. In a way they are still winning. Durant was sent to Brooklyn in ’19 for D’Angelo Russell, who was flipped for Andrew Wiggins, who played a key role on their ’22 title team.

Last season, with Golden State battling injury and off-court issues, the NBA celebrated perhaps its most competitive season. In the final two weeks of the season 26 teams were mathematically alive for spots in the postseason. Miami, the No. 8 seed, came out of the East. Denver, a franchise built from shrewd drafting, won the West. At the Finals, commissioner Adam Silver crooned that the NBA had “come up with a system . . . where I like to think every team in this league has a shot to compete for a championship.”

If the last CBA was about creating a system, the new one attempts to slam its loopholes shut. Consider: In February 2022, the Clippers acquired Norman Powell and Robert Covington from Portland. The deal tacked $20 million onto L.A.’s payroll—plus another $19 million in tax penalties—which Ballmer (net worth: $80 billion) was happy to pay. Under the old system, the Clippers could do the deal due to a rule allowing taxpaying teams to take back 125% of the outgoing salary. Beginning next summer, teams that are over the tax can’t take back a nickel more than they send out.

Flipping future first-round picks has been a useful tool for taxpaying teams. The Suns, when acquiring Durant, surrendered control of their picks through 2030. Under the new system, teams that cross the second apron are barred from dealing first-rounders seven years out. And with another infusion of television money due in ’25, the CBA legislates out another massive cap spike, limiting cap increases per year to 10%.

Success, the NBA believes, can be achieved now through only superior drafting and shrewd roster management. With one short-lived exception: a superstar with a no-trade clause bullying his way to a specific team that has an owner willing to eat the costs to bring him there—and a window to do the deal before the new rules take hold. “The cap spike was an anomaly that the Warriors took advantage of,” says a high-ranking NBA team official. “The Beal situation is another.”

In late August, Frank Vogel, months into his new role as Suns coach, settled into a folding chair inside a gym on the UCLA campus. He watched Durant flip in rainbow jumpers, Beal drop floaters and Booker knock down threes from all over the floor. He thought back to the talented teams he has commanded, including the Lakers, who won the 2020 title. “This is the most pure scoring that I’ve ever had as a coach,” says Vogel. “But we have got to make sure that our group is going to play as a team.”

The Suns will have more star power than any contender. More questions, too. Health, for starters. Durant has played in 58% of his teams’ games the past three seasons. Beal, 64%. Booker, usually durable, missed 29 games last season. They will need to figure out spacing—Durant, Booker and Beal are three of the league’s most prolific midrange jump shooters—and with Paul gone, Booker and Beal will be thrust into playmaker roles. “In the modern NBA, you play through your base at the top of the key a lot,” says Vogel. “I think the way the game has changed it de-emphasized the need for a traditional setup point guard. We’re going to be playing a different offensive approach that is a multiple-ballhandler attack.”

Egos will need to be checked. Vogel believes Durant, Booker and Beal will welcome a reduced burden. “None of them are young guys who are still trying to prove themselves or put up numbers,” says Vogel. In September, Phoenix jettisoned the disgruntled Ayton, swapping the center for a package of role players, including Jusuf Nurkic, Grayson Allen and Nassir Little. That decision, said Jones, was about finding the right pieces to complement the new Big Three. “When you add talent, when you add new players, the team shifts,” Jones explains. “And when the team shifts, you have a choice. You can stand still or you can improve. And so we chose the latter.”

The rest of the rotation, says Vogel, “will be a little bit of trial and error.” Phoenix’s midsummer bargain shopping was productive. It added Eric Gordon, a still-reliable perimeter scorer at 34; Drew Eubanks, a durable backup big; and Yuta Watanabe, who shot 44.4% from three-point range last season in Brooklyn. Before the Ayton trade, the Suns added seven players on minimum deals. (Even that was costly. The NBA reimburses teams a percentage of minimum deals. But when a team includes a player option, which Phoenix did for six of the seven, the reimbursement goes away.)

In short—there will be challenges. The Suns’ ability to pay anyone beyond its core is limited. If, say, Watanabe has a breakout year, Phoenix will likely lose him because it can’t match any higher offers for 2024. Yearly roster turnover will be a reality.

Asked to assess the riskiness of the Suns’ direction, Jones pauses. “I don’t think it’s a risk,” the GM says. “I think that’s the game. You’re always betting on something. You’re either betting that you can have victory by committee or you’re betting that you can do it by going top-heavy. You’re always betting on something. That’s the inherent risk of playing the game.”