Bill Walton's Unflappable Positivity Made Him One of a Kind

Among the multitude of Bill Walton’s unique traits, there was this: he rarely used periods in his communication. Not in texts. Not in emails. Really, not even when he talked—the words just kept flowing, of their own volition and in random directions, transmitted from a remarkable brain into the world.

Instead of periods, Walton punctuated his thoughts with commas. An example, from a text he sent me on March 6, 2020, just days before the pandemic shut down the world:

Thank you, for your kindness, and my life,

Shine On, Play On, Carry On,

BW,

I look forward to our next celestial encounter,

I’m off for a day of desert solitude, and all that goes with it,

It was as if he were speaking in lyrical form. Or, as I chose to see it, he was engaging in a conversation that would continue in perpetuity. As if the dialog would never end as long as you don’t put a period on anything. To me, those commas said, “to be continued.”

And so this is the saddest thing to me, on this sad day for Planet Earth (not just the sports part of Planet Earth, but the entirety of it): we have put a period on Bill Walton’s incredible life. There are no more commas. No more “to be continued.” No more “Shine On” texts to come.

His death at age 71, succumbing to a cancer battle few even knew he was fighting, is enough to make a man cry.

Walton is easily one of the 50 greatest basketball players in the history of the sport, and certainly one of the three greatest collegians (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bill Russell would be my other two). In three seasons of varsity eligibility at UCLA, he led the Bruins to two national championships, three Final Fours and a record 88-game winning streak that will never be surpassed. He led the Portland Trail Blazers to their only NBA championship in 1977 before foot injuries robbed him of so much, then came back to play a vital role on the Boston Celtics’ 1986 championship team. He was the greatest low-post passer the game has ever seen.

And yet those Hall of Fame accomplishments are such a small fraction of who he was and why he still resonated nearly 40 years after he stopped playing. After enduring a succession of ankle and back injuries and surgeries, Walton made it a self-appointed mission to be a beacon of positivity, a source of endless joy, a celebrator of the human condition. He treated many, many people very, very kindly.

He became the world’s most famous Deadhead. He became the world’s foremost appreciator of his college coach, John Wooden, despite—or because of—their generation-gap clashes when Walton was questioning everything and Wooden was steeped in basketball dogma. (“Everything he ever said—and I didn’t realize this as a teenager—came true.”) He became the world’s most unconventional TV broadcaster and, at the same time, the world’s biggest booster of the Pac-12 Conference.

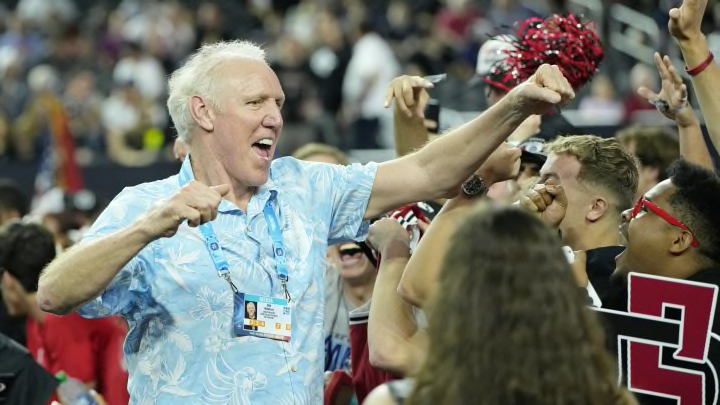

I first met the Big Redhead at the Sydney Olympics in 2000. His hair was no longer red and he was clearly hobbled, but Walton radiated happiness. He was working as a broadcaster for NBC from the beach volleyball venue at Bondi Beach, and the vibe was perfect for a San Diego hippie. Gratitude was his prevailing attitude.

To that point, Walton had worked for a decade on TV, mostly on the NBA. His final role, starting in 2012, was with ESPN and the Pac-12 Network as an analyst covering that league’s games. This was when Walton fully transformed into either your favorite or least favorite color commentator.

Walton resolutely refused to do the job by the book. Instead of a coat and tie, he usually wore a polo shirt. He brought padding for his chair, to alleviate his aching back. His commentary—all commas, no periods—veered everywhere, occasionally touching on the actual game being played in front of him. Rhapsodies and soliloquies, unconstrained. He tested a director’s structure and longtime play-by-play sidekick Dave Pasch’s patience, but the rapport between the two became its own endearing, odd-couple schtick.

The TV Walton could be an unapologetic ham. He was a wild practitioner of hyperbole. He got plenty of facts wrong. That drove some viewers crazy, but they were missing the point of a Walton broadcast.

Every game was a celebration—of basketball, yes, but also of life and art and whatever else traipsed through Walton’s mind. The broadcasts were two hours of free-form fun, an endless Jerry Garcia improvisational jam. Walton knew more about the game than anyone watching at home, but dissecting ball-screen angles was boring. There were so many other things to talk about.

Foremost among the other topics was the paradise of the Pac-12, the “Conference of Champions,” as Walton called it over and over. He served as the P.R. megaphone for a poorly run league that stopped winning big in football and basketball, extolling quality of life when the quality of competition dipped. The Pac-12’s cities and campuses and academics and weather were all unbeatable to Bill.

During one of our conversations, I told Walton that my daughter, Brooke, was a Pac-12 athlete at Stanford. He was delighted, asking a barrage of questions. The last question: can you give me her email address? I did, and Walton sent her a warm, supportive, congratulatory missive. He believed every good thing he said about life in the Pac-12.

The raiding of the league by other conferences was a sore point with Walton. That challenged his relentless positivity, so he largely opted to say little about it. When UCLA joined USC in shockingly fleeing for the Big Ten in 2022, Walton’s voice was the first reaction a lot of people wanted to hear. It was one of the few times he didn’t return my calls and texts.

Months later, Walton wrote a lengthy statement to longtime Oregon columnist John Canzano articulating his displeasure with UCLA’s move. The statement contained dozens of commas, zero periods. There is one thing fitting about the timing of Walton’s passing: he will never have to see the Bruins play in the Big Ten.

The last time I talked to Walton was during the 2023 Final Four. I was writing a column on the 50th anniversary of his most legendary performance , making 21 of 22 shots in the 1973 NCAA tournament championship game against Memphis. We were having trouble connecting, and then suddenly came this response to a last request for a phone interview:

Always for you, and SI,

I’m slammed,

What’s your deadline,

Thanks, BW

Walton made time for the interview. Slammed or not, we talked for at least 30 minutes. The more I asked him about his performance, the more he extolled his teammates—Jamaal Wilkes, Larry Farmer, Dave Meyers, Larry Hollyfield, Tommy Curtis, on and on.

“That was a good day for us,” Walton said. “I was the luckiest guy in the world.”

In reality, those who experienced Bill Walton—the player, yes, but more importantly the joyful citizen of the world—were the luckiest people in the world.

In his honor, we can all do our best to shine on, play on, carry on, and on, and on,