'Where's Waldo?' The Life (And Near-Death) Of Former DFW Sports Media Star Wally Lynn

Where's Waldo?

There he is. Surviving in a crowded Deep Ellum business loft.

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. No insurance. No sports. Modest job paused. Only a bicycle for transportation. Legal woes lingering.

For Wally Lynn, life couldn’t be … better.

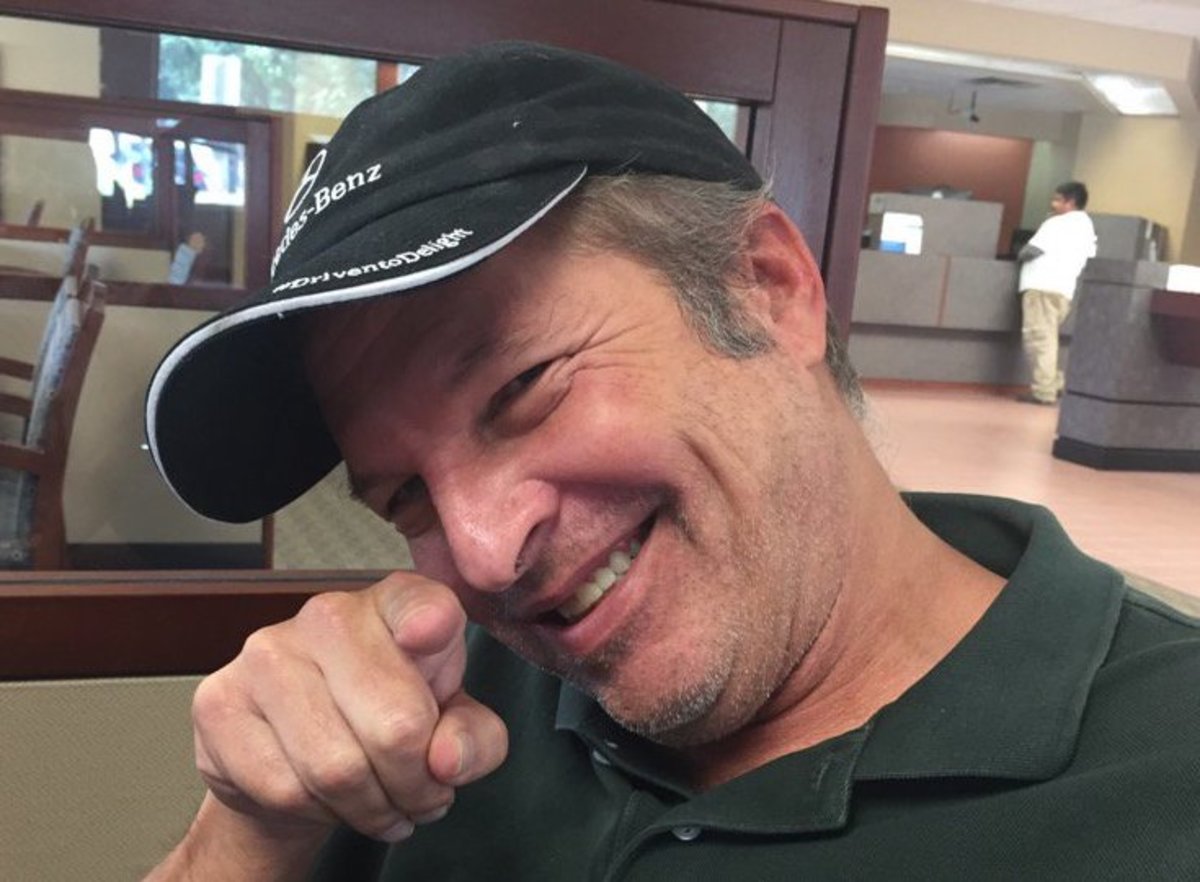

“I’ve weathered the storm,” the former radio star-turned-recovering alcoholic says after a long day helping friends renovate a house in Allen. “Lots of ’em, actually. All things considered, I’m doing OK. And I’m only going to get better.”

The twinkles of hope at the end of Waldo’s long, desperately dark wormhole? Court appearances temporarily satisfied and warrants removed, he can renew his driver’s license and no longer be forced to live on the lam. He has gainful – though menial and inconsistent – employment, and dreams of returning to a job in media. He is reconnecting with friends and family, specifically two sons he feared losing contact with forever. He is completely sober and, somehow through it all, impossibly sane. Perhaps most importantly, he has a pillow to call his own.

“Believe it or not,” says the 59-year-old, “on my way to becoming a real human being again.”

For the former Dallas-Fort Worth multimillionaire sports media personality who grew uncomfortably cozy with rock bottom, perspective is a powerful prism.

In the past four years alone, he’s unwittingly worked for an international drug cartel money launderer, been kicked out of a homeless shelter, slept in the dugout of a Little League baseball field, violated probation, pawned his paltry possessions, slinked off to San Angelo, earned food and shelter by being a “tamale slave” and attempted – unsuccessfully – to turn himself into prison.

“You go to the ATM and see a zero balance, and then they won’t book you into jail when you try to surrender, yeah, that’ll get your attention,” he says with a chuckle. “But I’m sitting here, living proof that things happen for a reason. For starters, it’s given me a monstrous appreciation for the little things. Like having a bed and a pillow. Not having to live in constant fear.”

And, to think, those episodes were after his fall from grace.

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Standing on a huge rock. Sitting on top of the world.

“I just wanna say that yes, in fact, I do know how lucky I am,” says Lynn, arms and heart wide open as he and his cup of Jack Daniel’s welcome a couple hundred guests to his 40th birthday party. “To have all y’all here, and to have experienced some of the wonderful things in my life ... I am truly blessed.”

With that, the man who has everything — fame, fortune, family and friends — gets a special gift from his wife, Kim, for this 2001 gala. She has arranged for a live concert by one of her husband’s favorite Texas musicians, Trish Murphy.

In his bank, Lynn owns shares of Yahoo stock worth $4.4 million.

On his mantel, he boasts numerous awards from a 15-year sports broadcasting career in DFW and a plaque commemorating his cameo speaking role in Oliver Stone's movie Talk Radio.

In his Allen home’s garage, he possesses multiple BMWs.

At the Plano restaurant Love & War in Texas, he has permanently reserved seats at the bar.

Under his wing, he cherishes his doting wife and two gifted sons.

Today, he’s piling on his embarrassment of riches by spotlighting his newest showpiece — a 77-acre ranch in Spicewood, just west of Austin and around the bend from Willie Nelson’s annual Fourth of July picnic. The spread features a main house with an outdoor shower and screened-in porch. Dotting the property are 100-year-old oak trees, plentiful deer, a boat for playing on the nearby Colorado River, a fleet of ATVs, a basketball court, a Wiffle ball field, homemade potato cannons, horseshoe pits, barbecue smokers and a large entrance gate painted like the Texas flag.

Welcome to Wallywood.

This ranch will eventually host concerts by Texas country artists Mike Graham, Roger Wallace and Cooder Graw, but tonight it’s the setting for the birthday boy to be sultrily serenaded under the stars. Torches and a fire pit strike the mood. The mammoth rock provides the stage for Murphy’s acoustic crooning.

Says Waldo, understandably beaming, “It doesn’t get any better than this!”

He has no idea.

Over the next 19 years, Lynn will endure one of the saddest, most dramatic riches-to-rags falls from grace in Dallas media. His nosedive will be littered with suicide, adultery, alcoholism, hospitalization, divorce, foreclosure, bankruptcy, embezzlement, arrests and a shattered surrender that leaves him hapless, homeless and wholly unrecognizable.

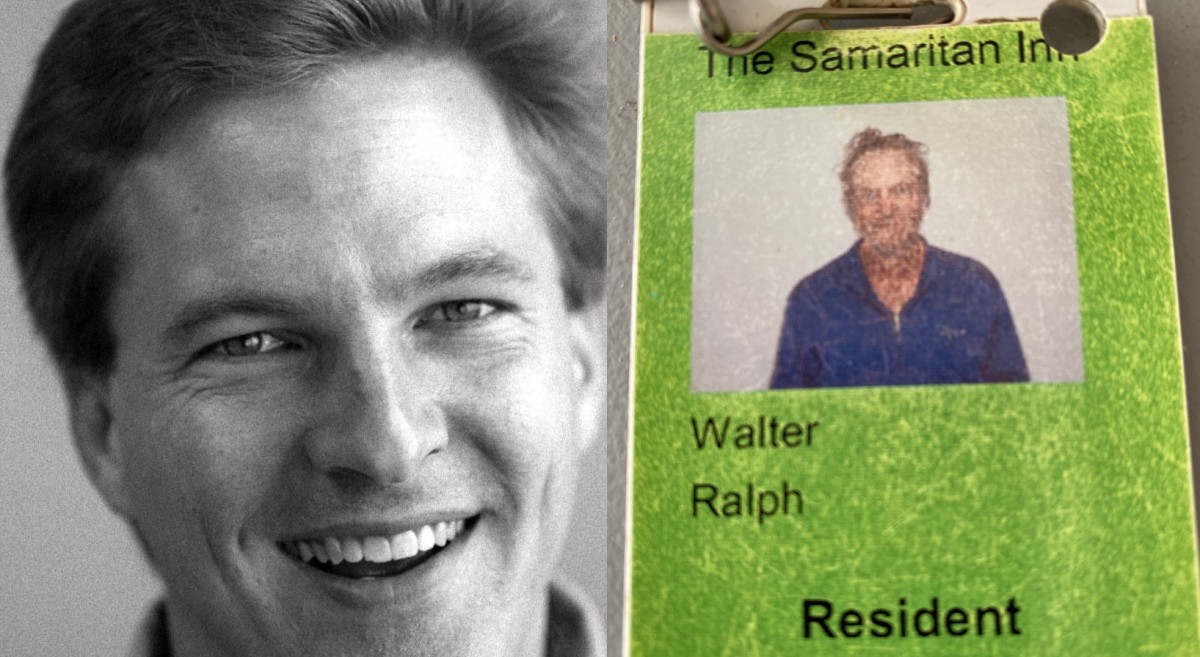

As a longstanding nod to his dizzying collage of projects, friends of Walter McMillan Ralph (he adopted the stage name “Lynn” to honor his mother) dubbed him “Waldo.” Like finding his cartoon character namesake, pinpointing where Waldo is and how he got here is difficult.

Perhaps it begins tonight at Wallywood, with a verse from Murphy’s new hit single, “The Trouble With Trouble.”

The trouble with trouble is, it starts out as fun.

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Growing up in Lake Highlands. Showing off in every crowd.

“He just had it,” says Jeff Coats, Lynn’s best friend since third grade, college roommate and best man in his wedding (and vice-versa). “He was the fastest guy in track. The funniest guy in class. He was just good, naturally good, at anything he did.”

The youngest of four siblings to parents Lynn and Pierson, Wally is decent at playing sports but delirious about talking sports. By the seventh grade at Lake Highlands Junior High in Northeast Dallas, he carries a hallowed spiral notebook. In it is crucial data — names, stations, air times, call-in phone numbers — about every radio and TV sports show in town. It’s his hand-scribbled, pre-Internet version of bookmarked websites, and it’s only a glimpse of his ingenuity.

“He was so quick, so witty, so funny,” says Anecia Drake, whose friendship with Lynn has persevered since 1974. “He could talk sports. He knew all about music and bands. Honestly, I think we were always secretly in love. But we were buds first, and we didn’t want to screw that up.”

As an adult, Lynn flawlessly plays Billy Joel on the piano, sings an eerily Sinatra-sounding Sinatra and — at the drop of a hat — performs spot-on impersonations of DFW sports icons Nolan Ryan and Michael Irvin. He never has a single music lesson yet plays the keyboard with Graham, strums a guitar alongside Murphy and produces a surprisingly infectious beat on a dilapidated washboard with Cooder Graw.

Says youngest son Mitchell Ralph, “He was so charismatic. He would walk into a room full of strangers and instantly put everyone at ease and make them laugh. To this day I have an appreciation of people and relationships because of him.”

He even somehow teaches music.

When Mitchell gets intimidated at the prospect of competing against a classically trained pianist in a junior high talent show, Lynn engages him with the family’s grand ivories. No sheet music. Just a laptop, finely tuned ears and talented fingers.

“I’ll be damned if Mitchell didn’t win that contest,” Kim Ralph says. “He beat the kid that played Mozart! By playing the theme from Rugrats. Rugrats! Wally just had a special talent to pick things up so easily and then put his little spin on it.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Behind the microphone. Ahead of his peers.

After graduating from Lake Highlands High School in 1979 Lynn goes with Coats to Southwest Texas State in San Marcos. There, fueled by a love of girls and partying but also a rabid disgust for rules and formality, they spearhead an infamous anti-social social club: “Spivs.”

Light-hearted, self-deprecating and named after men who “make a living via disreputable dealings.” the group revels in cutting corners and bending rules. The Spivs win a campus chili cook-off, only to be disqualified when organizers discover they sneaked into the competition to avoid filing proper paperwork and paying registration fees.

“We studied hard and did our work, but when it came to fun we weren’t above being a little bit mischievous, a little shady,” Coats recalls. “Before you know it we grew into this fraternity of 40 guys who all had in common a hatred of fraternities. Wally was a driving force of that. When he put his mind to something, it got done.”

After college, Lynn starts his radio career working the political beat at the Capitol in Austin in the early 1980s. But it’s mainly a resume-fluffer to take him where he’s always dreamed: talking sports in DFW.

By 1987, his doggedness, talent and versatility are attracting the attention of DFW radio icons Norm Hitzges, Brad Sham and Ron Chapman. Lynn launches his 24-year career at KLIF-AM 570, where he ascends to host highly-rated, innovative night-time sports talk shows with Leon Simon (The Sports Brothers) and, later, Mike Fisher (Wally & The Fish).

“Anyone could listen to Wally for five minutes and realize he was uniquely talented; funny man, anchorman, impersonator, smart,” Fisher says. “But even though he was on the radio, you also knew that like lots of us in this business, there is an ego – in Wally's case, one that made it seem like every day he was starring in his own personal TV show.”

During his eight-year run anchoring prime-time shows, he wins multiple Katie Awards from the Dallas Press Club and, in 1996, Lynn's revered accolade from the Texas Association of Broadcasters for “Best Live Segment.”

“The guy could do it all,” says Hitzges, who worked with Lynn at KLIF before jumping to rival The Ticket in 2000. “He had the news judgment. But if the situation called for it, he’d be goofy as all get out and make the audience laugh.”

While other shows talk vanilla football, Lynn colors outside the lines and spotlights two obscure Cowboys offensive linemen, Dale Hellestrae and Mark Tuinei. The award-winning bit of the Snapper and Pineapple Show stars Lynn’s live play-by-play (using a multitude of seamless impersonations, including Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones and iconic national broadcaster Jack Buck) of Hellestrae, the team’s long-snapper, zipping a ball into the rear window of a car driven by Tuinei through the players’ parking lot at Valley Ranch at 35 mph.

Although he later anchors Cowboys postgame shows on 103.7 KVIL, 98.7 KLUV and 105.3 The Fan; works for ESPN stations in Dallas and Austin; creates a Texas music Front Porch show for 99.5 The Wolf; and becomes the official radio voice of Southern Methodist University, the Dallas Sidekicks and Dallas Desperados, Lynn consistently highlights two moments of pride: Being the voice of the 2005 Ring of Honor induction ceremony for Troy Aikman, Michael Irvin and Emmitt Smith at Texas Stadium, and “the snap segment.”

“To think of something like that was crazy,” Lynn says. “To pull it off was even crazier.”

Lynn’s creativity is never more on display than one summer night in 1999 at Cowboys’ training camp in Wichita Falls. On the way to the local honkytonk, he wears mismatched shoes – one boot and one sneaker.

“I don’t know,” Lynn shrugs when a friend quizzes him. “Might be fun to see if people notice, and then see where my story goes from there.”

In the span of an hour he spins yarns about being “chemically imbalanced,'' “fatally forgetful,'' a “shoe sales intern,'' the “Cowboys’ tryout kicker” and an “alien.'' After being met at the club with a combination of skepticism, flirtation and laughs, he then transforms his late-night meal into a one-man comedy.

At Whataburger, Lynn pulls from his jean’s pockets two miniature Cowboys bobbleheads – because of course he does – and helps himself behind the counter. Ducking down to leave only the toys visible, for the next 20 minutes over the restaurant’s speakers he holds a running dialogue between Irvin and Cowboys’ safety Bill Bates. The two trade barbs, compare condiments, greet guests and abruptly and hilariously become annoyed when forced to pause their sparring to announce, “Customer No. 27, stop interrupting our show and come get your burger before we spit in it!”

By the time he leaves, Lynn prompts a round of applause, $8.50 in tips and an invitation from the manager to perform any time in exchange for a free meal.

During the drive home to his Midwestern State University media dorm, Lynn exclaims, “It’s great to be a dork!”

Based on the beauty in Lynn’s balance, there are no signs the homer will ever be homeless.

Despite working long hours that often require travel, he maintains passion for his marriage and quality time for his sons. He takes his oldest, Jake Ralph, to Cameron Indoor Stadium to watch a Duke basketball game. He coaches Mitchell’s baseball team, never missing a game.

Says Mitchell, “For the first 16 years of my life, he was ‘Super Dad’.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Popping Champagne. About to burst his bubble.

By the late 1990s, Lynn is enjoying sustained career success and the fruits of his relentless networking. A fan of his makes an introduction, which leads to him being one of the first 20 hires at a Deep Ellum startup company called AudioNet, with a boss named Mark Cuban. Engineered primarily as a way to hear college sports events over the Internet, the company covets Lynn’s voice talents and eclectic DFW connections.

“It’s going to turn your computer into a radio and a TV,” Lynn tells friends about his new endeavor in 1995. “I think it could be big someday.”

That time arrives in July 1998. AudioNet rebrands itself as Broadcast.com and goes public, with a record IPO that sends stock shares soaring 250 percent. Nine months later, on April 1, 1999, Yahoo purchases Broadcast.com for $5.7 billion.

Cuban instantly becomes a multibillionaire and begins eyeing ownership of the Dallas Mavericks. Lynn becomes a Yahoo employee, with stock shares worth $4.4 million.

“Pinch me! No, fucking punch me!” Lynn exclaims as he and a limousine full of friends celebrate while cruising along Belt Line Road in Addison. “Can’t believe this is real livin’!”

In February 2000, Lynn and three close friends – including Dallas millionaire entrepreneur John Eckerd – charter a private jet to the Daytona 500. At their rented mansion, they brazenly toast their lofty status. The quartet tears a $100 bill into four pieces and proceeds to wash it down with four difficult, definitive gulps of champagne.

The toast: “Here’s to never needing this $100!”

While Kim is cautious with the potential windfall - “I didn’t quit my job or even go crazy enough to buy a new mattress,” she says - her husband is intoxicated by his new tax bracket.

Waldo pays off his cars and house and makes a significant down payment on the $600,000 ranch. He continues speeding toward happily-ever-after through his birthday bash with Murphy and into 2002. It is here when something - karma? bad decisions? - triggers a bewildering series of unfortunate events that will ultimately strip him of all luxuries and erode everything he treasures.

It arrives in waves of death.

Of his radio career.

In streamlining its stations in 2000, DFW radio cluster owner Susquehanna makes The Ticket its lone sports station. The decision turns KLIF into a news outlet and ends Lynn’s run as its flagship sports voice. He goes to ESPN Dallas and ESPN Austin and returns to 105.3 The Fan for cups of coffee, but for the most part only dabbles in public-relations gigs representing local athletes such as Charles Haley and Tatu, and mentalist David Magee.

“He got too big for his britches,” Kim says. “One night, we fought about it, and he looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘I’m not like you people. I refuse to work 9 to 5.' So, he didn’t have a steady paycheck for 10 years.”

Of his fortune.

After the dot-com bubble bursts, Yahoo eliminates its broadcast services in late 2002, and Lynn is trimmed as part of mass layoffs. Gone are his job and much of the unvested stock that adorned it. Of the $4.4 million stock potential, Lynn realizes about $500,000 in cash. He is forced to sell Wallywood in 2005 and, after a slew of unsuccessful investments, eventually takes out a $100,000 home equity loan.

“Kim kept the steady job, kept the books,” says Coats. “Wally was the creative spirit always swinging for the fences.”

Of his friends and family.

By 2000, one of Lynn’s closest friends is Dallas construction mogul John Haines, a principal owner of Ridgemont Construction and the husband of Kim’s cousin, Leslie. The two share business dreams, compare expensive toys and embark on guys’ trips to watch Haines’ Nebraska Cornhuskers play at Notre Dame and Lynn’s Cowboys play the Green Bay Packers at Lambeau Field. Besieged by a sagging economy and marital problems, Haines kills himself on Aug. 20, 2008.

“Losing John obviously hurt everyone,” Mitchell says, “but the one that really began pushing him over the cliff was his mom.”

She dies in 2011 at age 89. In the span of three years, Wally loses two heroes.

“We visited at his mom’s memorial and it was again like we were peas and carrots,” says Anecia. “But something was a little off. For one, it’s the first time he smelled like alcohol.”

Of his marriage.

Exhausted by her husband’s chronic voids of affection and employment, in the summer of 2010 Kim moves out of their Allen home. They divorce in 2011, one month shy of their 23rd anniversary.

“I was lonely,” says Kim, who admits she was unfaithful. “My husband hadn’t paid attention to me for a long, long time.”

With Kim gone and Jake off to college at the University of Texas, it is just Lynn, Mitchell and a new, unwanted squatter. The drinking demon that netted Lynn a DWI in 2009 is blossoming into a raging monster.

Says Mitchell, “Out of nowhere, I started finding empty wine bottles all over the house.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. A recluse. In refuse.

By 2012, Lynn is a hermit. His drinking is escalating, his socializing evaporating. After he hits his son’s car in the driveway while driving drunk, Mitchell adds to his own daily chores.

“Had to hide his keys every morning before I left for school,” he says. “On weekends, he’d be drunk by the time I woke up.”

On several occasions, Mitchell calmly challenges his father.

Mitchell: “Dad, whatcha drinking?”

Lynn: “Water.”

Mitchell: “Really? That sure doesn’t look or smell like water. You sure?”

Lynn (through bloodshot eyes, slurred speech and rising anger): “Yes. I promise!”

“That broke my heart," Mitchell says. "Drinking was more important to him than being honest with me.”

When Mitchell leaves for college in the fall, Coats, a Collin County Realtor, persuades Lynn to sell his house. So detached is Lynn that he refuses to pack, one day calling friends to announce a free fire sale that includes his beloved piano.

“Come take it,” he says to multiple friends. “I don’t want any of this shit anymore.”

Now all but isolated from friends and family, Lynn continues to deteriorate. During brief interactions he declines job leads, claiming he has money “stashed away” and a job at Google.

“At one point he said he had a job at a radio station in Tyler and was going to move in with dad in Athens,” says Ben. “No one in the family believed it. We just wondered what he was doing for money.”

After discovering the house is on the verge of foreclosure, Coats does the heavy lifting. He organizes an estate sale, secures a storage building near The Golf Club at Twin Creeks for the bulk of Lynn’s remaining stuff and helps him rent an apartment in north Plano, just off the Dallas North Tollway and less than 100 yards from Coats' house.

“He was going downhill pretty fast,” Coats says.

Throughout the next couple of years, Coats regularly checks on his friend. He can, after all, see Lynn’s apartment across the Cul-de-sac from his Plano back porch.

“I mean, he was OK. Surviving,” says Coats. “He had no motivation. No get-up-and-go. I’d see him shuffling slowly to the Tom Thumb across the street. He was like a zombie.”

Says Mitchell, who visits the apartment during stints home from college, “It was just dark and sad. I’d drag him out to a movie or to get crawfish and he’d just beg to leave as soon as we got there.”

One day Coats receives a call from the storage company. Lynn was a couple of months behind on his rent, and the unit was about to be seized, its contents sold as compensation. Notified of his possessions’ peril, Lynn shrugs.

“Fuck it,” he tells Coats. “Let 'em have it.”

Included in the belongings: Every family photo album and video, engraved and antique silver passed down through generations of his family, even some of his mother’s award-winning paintings.

“I get nauseous just thinking about it,” Kim says. “The stuff we’ll never see again.”

After a lengthy period of radio silence, Ben Ralph visits Wally’s apartment in 2015 to find his brother on the floor, motionless, in a stupor. The following morning, he drives Lynn to the Serenity House treatment center in Abilene. Upon intake, staff members call 911, and Lynn is rushed to a nearby hospital’s ICU with alcohol-induced encephalopathy (swelling of the brain and disorientation). He stays there for 30 days, followed by back-to-back rehab stints in both the Abilene and Fredericksburg centers of Serenity House.

Upon his return to DFW, he tells friends about his moment of clarity.

“It’s pretty scary stuff, what I did to myself,” Lynn says. “I’m lucky to be alive.”

It is dramatic.

It is bullshit.

In May 2016, another spell with zero communication.

Ben and Leslie, Kim’s cousin, arrive at the apartment for a welfare check. No answer. They summon Coats, who brings a duplicate key.

The place is filled with what Ben estimates “must’ve been 1,000 beer cans.” Coats says the garbage — pizza boxes, unsecured trash bags and rotting fast food — rose from floor to countertop. On a table is an eviction notice, next to several uncashed checks written to Lynn from his father, Pierson.

“The whole place was a biohazard,” Ben says.

Lynn’s condition is even more gruesome.

They find him lying on the bathroom floor next to the base of the toilet, covered in feces, urine, confusion and the unmistakable stench of surrender. He is seemingly paralyzed, only able to marginally move one hand while repeatedly muttering, “Gotta find my shoe …”.

“He was on the brink of death,” Leslie says. “Emaciated almost beyond recognition. Totally immobilized.”

The paramedics estimate Lynn has been in that prone position on the floor for more than 24 hours and would have been dead in three more. He is taken to Plano’s Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but walks out in the middle of the night and shows up at Coats’ house the next afternoon.

“Drunk and scared,” Coats remembers. “He said, ‘I’m broke, and I don’t know what to do.’”

Coats rents a room at a nearby hotel and provides fresh clothes. He tells Lynn he will be back in a few hours, asking him to be showered, dressed and prepared to turn over a new leaf. When Coats returns, he finds Lynn sprawled over the bed in the same clothes and with the same, distinct smell: Alcohol, with a shot of apathy.

“At that point, it was hard to tell if he was freshly drunk or just residual drunk,” Coats says. “Either way, that was it. I was out of options. He was out of options.”

Coats throws Lynn in the shower, takes him to his house and packs a suitcase full of clothes and toiletries. Then he makes the most difficult drive of his life. He takes his best friend to a homeless shelter.

As he leaves Lynn at The Bridge in downtown Dallas, Coats begins bawling.

“I felt like a total loser,” he says. “But in this situation, there are no winners.”

The plan is for Lynn to receive professional help at The Bridge Homeless Recovery Center near Dallas Farmers Market. Friends and family commit to checking on his progress, to visiting him. He is admitted on May 17, 2016. On May 20, according to a volunteer, Lynn has a shower, a hot meal and … poof.

Just like that, he is gone, blending into the unseen sea of Dallas’ almost 4,000 homeless people. Qualifying for neither an Amber nor Silver Alert, Lynn is simply a missing person.

“At first, I figured he’d just show up at my house,” his brother says. “But after a couple weeks, I couldn’t stand the thought of him out there. Had to try something.”

Looking for a broken 55-year-old man who has been in and out of hospitals and rehab and likely will refuse their help, Ben and Coats recruit friends to spread the word about Lynn’s status. There are daily searches downtown. A report circulates in the local media, which prompts public interest, offers of free services from off-duty Dallas police officers and private investigators, and social-media sharing from an array of former Lynn associates, including Hellestrae, Hitzges, Fisher, Dale Hansen, Mike Rhyner, Newy Scruggs and Cuban.

“That’s horrible,” the Mavs owner writes in an email after reading of Lynn’s disappearance. “Anything I can do to help just let me know.”

Lynn deteriorates into a human needle in a homeless haystack.

Tips lead to the Union Gospel Mission, the Dallas Public Library, an encampment under I-30, random convenience stores and an abandoned building on Cadiz Street. It is gut-wrenching, fruitless stuff, providing no signs of Lynn but instead a pathetic peek into an un-civilization of blank stares, methodical meandering, babbling about nothing to no one and the ambiance of suicide so thick it feels like hot air breathing on the back of your neck. His search party finds depression and despair, but no Lynn.

Then, on July 1, 2016, a worker at Hitzges’ charity of choice, Austin Street Shelter, alerts the talk-show host that Lynn has been located. Hours later, Lynn borrows a cellphone and calls Ben.

After 44 days on the streets, Lynn says simply, “I’m ready to come home.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Surprisingly sober. Shackled.

As Lynn moves in with Ben in the tiny Collin County town of Fairview, his support system is reinvigorated.

Friends launch a GoFundMe campaign that raises almost $6,000 to help pay for clothing, luggage, a cellphone and laptop computer. A McKinney dentist provides free services. Peers who have experience battling addiction, including former Dallas Stars play-by-play voice Ralph Strangis, reach out to help.

Writes Strangis to Lynn, “It might just help to have another addict in the room to talk to.”

In an attempt to convince Lynn that people are still rooting for him despite his bad decisions and worse consequences, friends print and demand he reads 300 pages of well-wishes sent via email, text and social media messaging during the search.

“I’m shocked by this outpouring,” Lynn says. “It’s embarrassing, actually.”

His debt is being paid down. His spirits being lifted up.

Until he finds himself in jail.

In late September 2016, Collin County Sherriff’s officers show up at Ben’s door with a warrant. Lynn is taken away in handcuffs. In a phone call to a friend from jail, he attempts to explain.

“I had some unpaid tickets for sleeping in public, things like that,” Lynn says. “Not that big of a deal. I hope.”

It is a lie … to cover up a bigger lie.

Lynn isn’t behind bars for snoozing on a park bench, but rather for embezzlement against his family. The official charge is “misapplication of fiduciary or financial property between $30,000 and $150,000,'' a third-degree felony.

Suddenly, shockingly, the family gets its answer to how Lynn made ends meet all those years without a steady job. Leslie’s suspicion is what led her to accompany Ben to Lynn’s apartment earlier that year.

“I heard through family he wasn’t doing well,” Leslie says. “I tried to contact him, and when he finally responded, he said he was going to be ‘out of pocket’ for a while. I’ll admit, I was a little nervous about that man overseeing my children’s trust fund.”

After John Haines' death in 2008, his construction company partners bought out Leslie’s stake. Part of the package was a $200,000 trust fund for the Haineses’ two children, to be controlled by a close friend or family member of John’s — Lynn.

“He was a father figure to my kids,” Leslie says. “We had already put Wally in our will in case something happened to us.”

With Lynn designated as the lone signee on the account, Leslie is unable to check either the individual transactions or the balance. It isn’t until she hears him connected to terms like “addict” and “rehab” that she turns proactive.

Amid the filth of the apartment back in May, Leslie discovered trust statements detailing multiple linked accounts to different banks, confirming her worst fears. Her children’s nest egg had significantly dwindled after repeatedly being drained by transfers to an account belonging to Lynn.

“This was no longer just a sad story,” Leslie says. “It was a scam to steal money.”

She takes her findings first to the hospital, where she confronts Lynn and gets a videotaped confession and apology. Then she goes to Plano police, where detectives subpoena all involved accounts and corroborate the crime.

The conclusion: From 2013-15, Lynn transferred $70,000 in increments of $5,000 to $10,000 from the Haineses’ trust fund into his personal checking accounts. That alone isn't necessarily a crime, since he is authorized as the sole signee. But the investigation reveals that Lynn’s account was opened with a deposit from the trust and that correlating purchases were for rent, utilities, groceries and alcohol, not for the betterment or benefit of the trust.

As giddy as it was at the relocation of Lynn and his signs of sober life, the family exudes mixed responses about the revelation.

“I never in a million years thought that man could sink that low,” says Kim.

Counters Mitchell, “I wasn’t shocked at all. After he lied to me about what was in his cup, it was clear he was just a stranger in survival mode.”

Lynn is charged in June 2016, and a warrant is issued for his arrest. By this time, perhaps not coincidentally, he has disappeared into Dallas. Preparing for him to resurface, Leslie provided police the names and addresses of his closest friends and family, leading to the knock at Ben’s door.

“I wanted to give him the benefit of the doubt,” Leslie says. “Maybe at first he was just going to borrow some money, with plans to pay it back. Then maybe he got in over his head? All I know is the Wally I knew would never do this to my kids.”

Lynn sits in jail in McKinney for 77 days. Leslie helps negotiate his release, pleading with the district attorney to allow Lynn to work and pay back his debt rather than be locked up.

Upon his release, an upbeat Lynn is asked whether he’d rather spend a night in the gutter or a night in the slammer.

“Thanks for the appealing choices,” he jokes. “Give me the gutter any time.”

He pleads guilty and is sentenced to 10 years in prison but receives probation dependent upon him maintaining gainful employment, paying regular restitution to the trust and reporting monthly to a probation officer.

With a job in the offing, roof over his head and pillow under it — all thanks to his longtime friend and millionaire entrepreneur John Eckerd — Lynn spends late 2016 and early 2017 daring to dream about his future.

He mulls launching a podcast. Ponders how he can acquire a car. Attends a Christmas party with friends. Spends time with family, even briefly reconnecting with his sons. He drowns his sorrow over a Cowboys playoff loss not with alcohol, but his other vice, country music.

It’s a long way from the millions and the radio and the ranch, but it suffices for happiness.

“I can’t believe what I’ve been through,” he tells a group of friends sitting around the party’s Christmas tree. “What I’ve put people through. There’s no way I can ever make up for it.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. In lethargy. Out of options.

By the spring of 2017, Lynn’s motivation is AWOL, and destitution is increasingly becoming his destination.

Eckerd, the latest in a long line of helping hands, provides his friend with a simple job and a sterling shelter, his $1.2 million guest house in McKinney. The residence doesn’t come with three square meals per day, but is equipped with a pool, hot tub, game room and only two other roommates to share the five-bedroom, six-bathroom, 7,900-square feet of ostentatious space. For $0 rent, Lynn has the run of the house and the luxury of an upstairs bedroom, complete with big-screen TV and private bath.

The caveat is the job. All Eckerd asks of Lynn is to check with him each day before 9 a.m. to see what help is needed. To earn a paycheck, begin restitution to the Haineses’ trust and fulfill the terms of his probation, Lynn simply must be available and stay accountable.

It’s too much to ask.

During his three months in the house, Lynn meets his job requirement fewer than 10 times. There are no signs of alcohol, but also no glimpse of gumption. When chided by Eckerd about shirking his nominal duties, Lynn listens and nods and agrees and understands and rarely awakes before noon. Similarly, Lynn never responded to Strangis.

“Beyond frustrating,” Eckerd says. “People are giving him every opportunity to get back on his feet, but the old Wally just isn’t there. There’s no light in his eyes or fire in his belly. You can’t help those who refused to be helped.”

Upon hearing that Lynn is about to wear out his lavish welcome, Drake attempts to re-boot his focus via a June road trip. She drives him to Athens to see his father, making a detour at the Jacksonville Tomato Festival. Though the two semi-sync through light laughter and shallow small-talk, Drake spots troubling signs. Lynn draws a blank about their long, shared, passionate disdain for cheesy songs such as “Billy, Don’t Be A Hero.” During a pit stop at a roadside restaurant, he veers from his stated trip to the restroom ... straight to the bar.

“I caught him just staring at the rows of alcohol, like he was salivating,” Drake says. “When he finally came back to the table I asked him what he was doing at the bar. He said he was getting some napkins. But that didn’t make sense. We had napkins at our table. Plus, he was just in the bathroom. Something just wasn’t right with him. Not the same old Wally.”

Counters Lynn, “I was watching the Rangers game on the bar TV. No big deal.”

Drake informs Lynn’s sister about his erratic demeanor and behavior. The two reason that his previous drinking episodes have prompted a neurological disorder that impedes his ability to perform even the most basic of tasks. And to accept consequences for his actions.

“He’s like a 14-year-old,” says Drake. “He can’t – or won’t – multitask. Simple things like unloading the car was a major ordeal because he had to carry one item at a time.”

Drake and Lynn's sister briefly consider an attempt to have the State of Texas declare him mentally incompetent in order to get him a guardian to help manage his affairs. It’s an expensive, complex and heart-breaking process. One especially daunting when Drake isn’t fully convinced Lynn’s aptitude is being mitigated by his attitude.

By August, Eckerd prepares to sell the guest house. Long since weary of wasting energy and expenses on Lynn’s aloofness, he tells him to move out.

“I reiterated that I tried to help and that he hadn’t held up his end of the bargain,” Eckerd says. “But he just shrugged and mumbled. If I didn’t know better, I’d think he didn’t give a damn.”

Says Lynn of his post-Eckerd predicament, “It’s going to be real hard to find a job without a car.”

The consensus: No matter what his support group does, Lynn will focus on living low, getting high and running from his past, in turn sabotaging his future.

“I don’t think this movie ends well,” says Anecia. “I hope and pray that I’m wrong, but I just don’t see him snapping out of it.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Fleetingly in a hotel room. Forever incognito?

Lynn’s bleak options are a transient existence of covert bouncing among homeless shelters, or 10 years in prison for absconding on his probation in case No. 401-83250-2016-2. Because he’s paid back only $3,000 of the $70,000 he siphoned and has stopped meeting his probation officer, the Collin County Sheriff’s Office will soon issue a warrant for his arrest.

“Dead or in prison,” Mitchell says. “I’ve been expecting one of those two phone calls about him every day for the last six years.”

As Ben, and a group of Lynn’s friends prepare one last crutch in the form of housing, money and a plan, they take inventory. Lynn never responded to the invitations from Strangis or prominent DFW radio voices J.D. Ryan or Kevin McCarthy, each with similar experiences and wisdom to impart. The group surmises he never read the 300 pages of supportive missives. He blew his golden gig with Eckerd. And as he’s chauffeured around McKinney to look for his next address, he recoils at the sight of unsavory, low-income options.

“I think he’s beyond help,” says Ben. “He won’t lower himself to his reality. Despite all he’s been through and all he’s wasted, he still has this attitude about him.”

It’s a stiff upper lip, now adopted by many of Lynn’s injured inner circle.

“I’m pleasantly surprised that he’s still alive, because to me he’s just taking the long road to suicide,” says Leslie. “I hope they find him. He should pay what he can to make it right with our family. That said, it’s not like I’m going looking for him.”

Says Mitchell, “Even if he found a way to stay sober the rest of his life, he won’t be a part of my life whatsoever. Unless something drastically changes, the severe damage he’s done to himself physically and psychologically is irreversible.”

With two weeks prepaid rent, $600 in his checking account, working cellphone and laptop, new bicycle and seven walking-distance job leads waiting in his email, Lynn checks into Room 103 of the McKinney Motel 6 on White Avenue at 10:30 a.m. Aug. 28.

There is sporadic communication via Facebook messenger, but just 18 months after vowing to leave the streets, Lynn seems determined to win his game of hide-and-don’t-seek.

“Let’s face it, we rescued a guy who didn’t want to be saved,” Ben says. “What a shame. What a big give-up. It’s sad, but it also makes you mad.”

Homelessness is merely his trade-off for an off-the-grid life where hygiene is optional, time is irrelevant, past transgressions are muted and consequences can be ignored.

With financial support from family members cut off, Lynn has no known sources of income.

“I’ll love my Wally until the day I die,” Kim says. “But it’s the saddest thing ever because that person is gone.”

Says Mitchell, “Walter Ralph might still be alive, but my dad died a long time ago.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. In desperation. In a panic. In a taxi.

“Spending your last $10 on a ride to take you to check yourself into prison,” Lynn says now, in retrospect. “About as bleak as it gets.”

He claims he applied to 10 jobs in person, and countless more online while living at the McKinney motel in late 2017.

“You know how hard it is to get a job when you can’t pass a background check?” he says. “Or even provide an ID out of fear it’ll get you arrested?”

His ATM balance turns up goose eggs. He pawns his laptop bought with the GoFundMe money. Same for the bicycle, which he sells at Play It Again Sports for $17 when they won’t hire him.

Out of money and past E on options, on Sept. 10 Lynn grudgingly decides to take the lesser of two evils.

The taxi takes him to the Collin County Jail, where he presents himself for surrender.

Says Lynn, handing the clerk his driver’s license. “I violated my probation and I’m turning myself in.”

Retorts the woman after a few computer clicks and a quizzical look, “Nope, sorry. I don’t see anything under your name. You’re not in the system.”

Lynn, turns out, was even bad at being bad.

Bittersweet is when surrender is cut off in traffic by salvation. It’s the ultimate failure, bogarted by a Hail Mary chance at success.

“In hindsight, there was a reason I didn’t go to jail that day,” says Lynn. “I can still be a productive citizen.”

Two defense attorneys with knowledge of Lynn’s case agree that if he would’ve been in the system on that day in 2017 – his probation violation wasn’t inputted until Nov. 6 – he’d still be in prison in 2020.

At the time, however, the unfathomably fortunate break is lost on Lynn. With nowhere to go and all life to get there, he aimlessly shuffles – on foot – through McKinney, back east across Highway 75 and toward the general direction of the motel he could no longer afford. One block shy, he meanders into a place he loved in his previous life. A joint offering cold beer, hot barbecue, friendly folks and Texas music – Hank’s.

Stinking of homelessness and drenched in despair, Lynn sidles up to the bar and stares at nothing. Until, that is, he is interrupted by a bouncer. Straight out of WWE – sent by an angel? – the bouncer is big, brawny and, who knew?, bubbly.

“I kid you not,” Lynn swears. “He said his name was Priesthood Rito.”

Next thing you know, Lynn is hiding in plain sight: Eating a free cheeseburger and washing it down with his favorite, Dr Pepper. They talk sports. Music. Life. In the end, Lynn finds a place to sleep. Hank’s loading dock is no Ritz-Carlton, but for five nights it feels like Utopia.

In “It’s a Wonderful Life,'' Jimmy Stewart had Clarence. In “It Once Was a Wonderful Life,” Wally Lynn has Priesthood Rito.

Eventually, however, bouncers gotta bounce. Rito informs Lynn he can no longer spend his days inside Hank’s or his nights out back. Sensing Lynn is void of compass and clue, Rito tells him to hop in his truck.

The Samaritan Inn in north McKinney takes homeless by appointment only, and there is an extensive waiting list. But the well-connected Rito knows all about cutting in line, and Lynn will get a bed in a room with three other men.

Tomorrow.

On an early October night, Rito accompanies Lynn across the street from the Samaritan to a baseball field. Kids are practicing. Parents, previously watching, dart their skeptical eyes toward the sore thumb in tatters. Before leaving, Rito assures the parents that his friend is harmless.

Lynn watches practice. Waits for the field to clear. Then, around 9 p.m., strolls into the third-base dugout, wads his duffle bag of clothes into a pillow, climbs onto the metal bench and curls up for what passes as sleep.

At 9 the next morning, he is officially homeless no more.

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Thumbing a ride to … anywhere.

The Samaritan provides room and board, but only if you have a job. Without one for six months, Lynn is being evicted.

Via Facebook messenger, in March he contacts a friend.

“Getting kicked out tomorrow,” he says.

Responds the friend, “Ever been to San Angelo? It’s either there, or prison.”

The friend just happens to be headed west for a tennis tournament. During the four-hour drive they sketch out Wally’s new world. He will be dropped off at the Salvation Army with $500 and a pat on the back.

“San Angelo, huh?” Lynn ponders along the way. “Sure. Sounds as good as anywhere.”

The city, 200ish miles west of Fort Worth along I-20, proves the perfect elixir for Lynn’s particular brand of illness. He lands jobs – sans background checks - working in a meat market, painting houses and gathering pecans. On a tip from a tenant, in November Lynn graduates himself from the “Sally” to an upgraded shelter/mission, Joshua 1:2 Fellowship.

Between incessant sermons served by pastors Mike Suarez Jr. and Victor Gutierrez, regular fistfights between tenants and interesting characters - one man was determined to hitchhike from San Angelo to attend the famed Sturgis Bike Rally in South Dakota - Lynn excels at his non-paid, intake job that grants him exclusive computer privileges.

He is also, conversely, forced to be a dreaded “tamale slave,” which requires him to make, roll and sell the rolled-up meat outside bars late at night - without keeping any profit, including tips.

“I’ve had some crappy jobs,” Lynn says, “but that might be the worst.”

Gaining confidence and strengthening his gumption, Lynn reboots his media DNA. When the Salvation Army shutters, its homeless population wanders into Joshua Fellowship. Lynn’s news judgement sniffs headlines, and hops on the phone.

“All the TV and radio stations came down with their cameras and did the story,” he says. “The pastors at Joshua were amazed. They kept asking ‘How’d you do that?!’’’

With a sense of trust built with local media, Lynn later gets publicity for a car-detail company that wins a 55-county-wide car-repair award. He then promises pastor Gutierrez - married with five children under 8 on a monthly salary of $325 - a new car, complete with publicity for the mission. Lynn talks a local Chevrolet dealership into donating the car and, presto, goodwill all around.

Interviewed by multiple stations for his good deed, Lynn emails a link of the TV stories to his brothers, Ben and Charles.

“That’s when it all started to change,” Lynn says. “I had hope that I still had it, ya know?”

Surprised and impressed, the brothers drive from Dallas to San Angelo. Ben buys Lynn a new cellphone. Charles leaves him with some cash. Icy family relations began to thaw.

“They started to believe in me again,” says Lynn. “I could tell they weren’t giving up on me. I can’t tell you how much that meant to me.

“After I made that car happen, it was an avalanche of goodness.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Working in Deep Ellum. Not far from where he started with Cuban 25 years ago.

Lynn moved back to Dallas in February. He lives in Deep Ellum, in the spare spaces of Charles’ architect business. He works a bike ride away, formatting iPads for firemen after connecting with an old tech-savvy friend from Cuban’s company.

He also has tentative, lucrative plans to ghostwrite a book for an old friend.

“Things are definitely looking up,” Lynn says. “So many people have helped me along this journey. It’s my turn to make something of my life and make them proud.”

He chats regularly with Mitchell and last Thanksgiving took a bus from San Angelo to San Marcos to Austin to reconnect face-to-face with Jake.

“The fences are slowly being mended,” Lynn says. “I told Jake I was sorry for everything, and that I loved him. Then we had a good cry. I was determined not to die without having talked to my sons one more time.”

On his bucket list of redemption is Leslie. Lynn says he intends to resume restitution payments and, eventually, initiate an uncomfortable conversation.

“I want her to be happy,” he says. “I want to talk to her at some point. Lot of things I need to say.”

Ben continues his successful insurance company. Same with Coats and his real estate business. Kim moved to Alabama to live with her mom and stepfather. Jake is in restaurant management in Austin. Mitchell is in law school at the University of Michigan.

Leslie works as a CPA in Dallas. Her children, Griff and Mae Grace, are both in their 20s.

Lynn has the freedom to move around and make plans because earlier in March he went back to jail. Counseled by an attorney, he turned himself into the same Collin County Jail, was booked, held for three hours and bailed out as a man without a warrant.

“It’s just good to not to be concerned with being picked up and arrested around every corner,” Lynn says. “That hiding. That worrying. It weighs on your mind. More than you realize. It can eat you up.”

As the lengthy legal plea bargaining commences, everything from probation to prison remains on the table.

“I hope the judge will understand that I’m better off out here making money and trying to make amends than I would be locked up,” Lynn says. “I want to pay back what I owe. Every penny.”

Where’s Waldo?

There ... no ... Here he is.