Where will NFL offenses go from here?

Tim Tebow made the zone-read famous in the NFL last season. (Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated)

The wheels are turning inside Rich Rodriguez's mind. Even in conversation over the phone, that much is obvious.

The topic that has Rodriguez, prepping for his first season as head coach at the University of Arizona, so enthused: Could a dual-threat player, like his former star at Michigan, Denard Robinson, elevate the zone-read spread option by lining up at running back, with an athletic quarterback next to him?

"I've always wondered about that," Rodriguez says. "You can take a Hines Ward (a college quarterback) or someone and get him eight to 12 snaps in something other than the wildcat. ... I wouldn't be surprised if it comes to fruition -- a multi-position guy; a guy that can actually throw the football, run some zone-read, play-action pass. [That] would be invaluable to that offense."

This, in a nutshell, is how most football schemes are created -- a new idea spurred on by the possibility of something great. In the end, great offenses and defenses often do not come from coaches sitting at a table drawing up plays for hours upon hours. They come from a spark, a random moment of good fortune that paves the way for something huge.

Such was the case with the zone-read play that Rodriguez is widely credited with creating and which Tim Tebow so famously brought to the NFL stage last season. That design came about almost entirely by accident during Rich Rodriguez's time as head coach at tiny Glenville (W.V.) State. As Rodriguez told SI's Tim Layden in Blood, Sweat and Chalk, his quarterback at the time, Jed Drenning, bobbled a handoff attempt out of the shotgun and, instead, kept the ball and bolted to where a defensive end had vacated his position.

"Why did you run that way?" Rodriguez asked Drenning, as recounted by John Bacon in Three and Out.

"The end pinched," Drenning replied. "I hit 'em where they ain't."

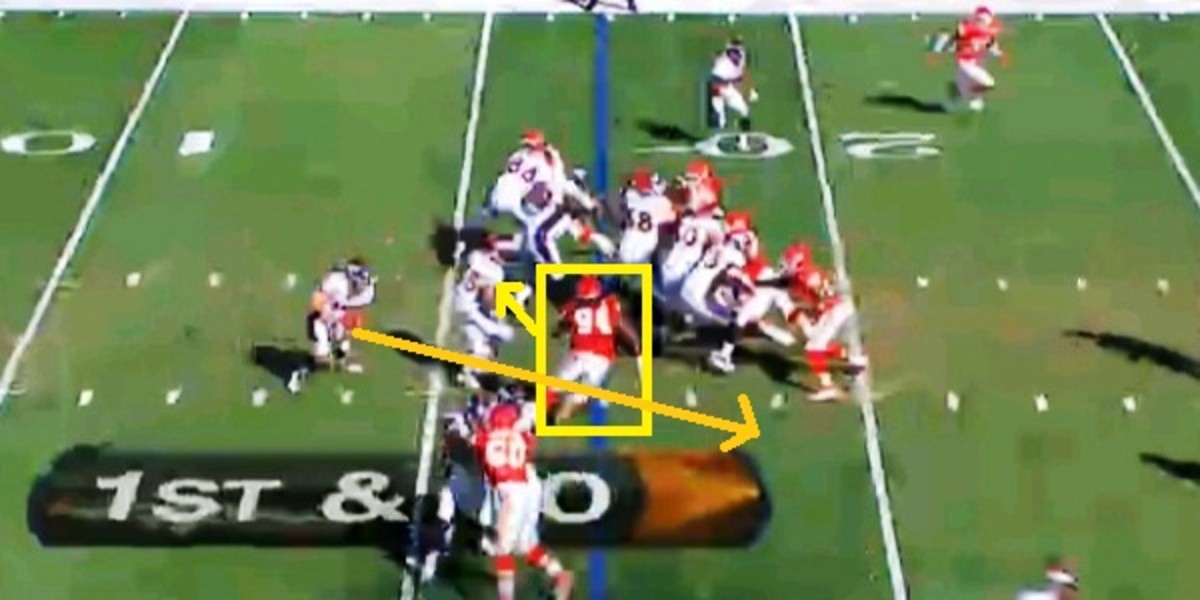

The Chiefs' switch in 2008 to a spread offense with a pistol formation came from similarly humble beginnings.

In hopes of sparking their offense and helping Tyler Thigpen, a third-string QB forced into action by injury, head coach Herm Edwards and offensive coordinator Chan Gailey incorporated elements of the offense Thigpen had run at Coastal Carolina -- putting the Chiefs on the cutting edge of the spread-to-pass craze that has swept the NFL in recent seasons.

Given the seemingly random nature in which these fads were born, predicting what's next for NFL offenses isn't easy. But we do know that they have evolved tremendously lately, and will continue to do so in the future.

Consider this, then, an educated guess of what NFL offenses could look like in 2012 and beyond, and what those schemes would mean for the play between the lines.

Pushing the boundaries of the zone-read

The basics of the zone-read go back to that day Drenning kept the ball and ran outside on a whim. On the most generic of zone-read plays, the quarterback starts with a back next to him in a shotgun formation, and the two set up for a handoff after the snap.

What happens from there is up to the QB. If the backside defensive end crashes down on the running back, the quarterback pulls the ball out and takes off with it; if the end stays home, the quarterback completes the handoff and the running back hits a hole up the middle.

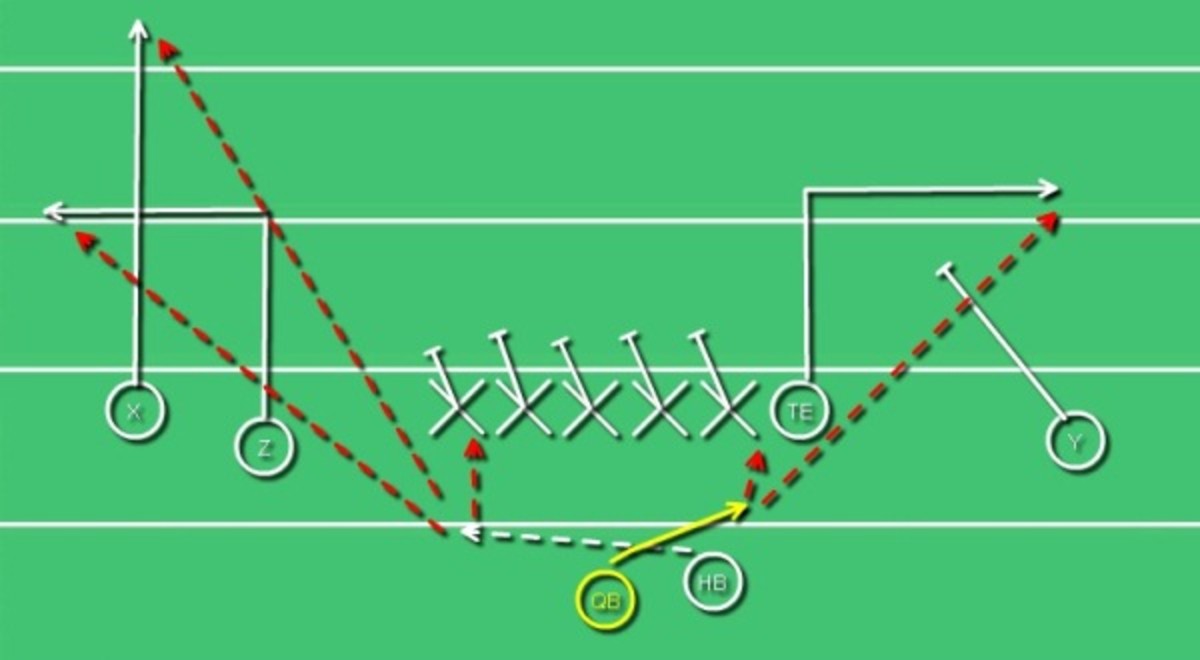

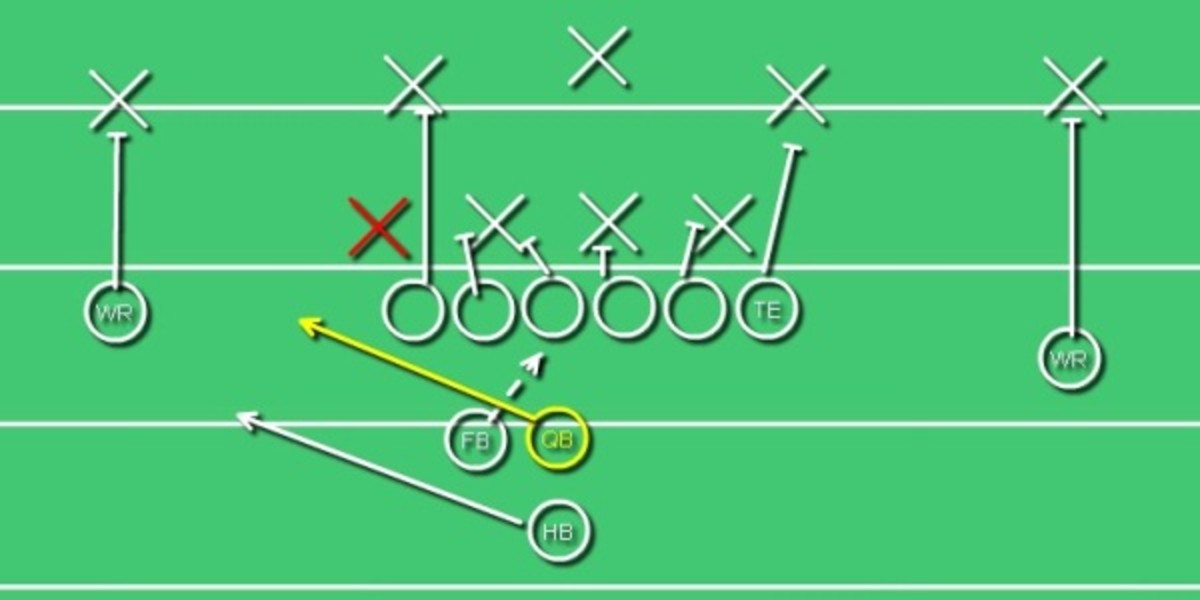

Offensive innovation and defensive adjustments have led to the ongoing expansion of this basic zone-read package, which has had a foothold in the college game since Rodriguez brought it to West Virginia and Urban Meyer took it to Florida. As NFL defenses adjust to more wide-open offenses, offensive coordinators will look for ways to expand and diversity those attacks. That brings us back to the hypothetical fired Rodriguez's way: What if a team like his, so reliant on the zone-read, replaced its running back with, in essence, a second quarterback on the field to generate something like this (the second quarterback is still labeled "HB" below):

Here, a team could run a traditional (or non-traditional) zone-read play. It also could run play-action or a straight pass play with its normal quarterback. But, the real kicker: It could call a play that involved both a handoff and a pass -- the ol' halfback pass trick, but with a QB-level player throwing, not a traditional running back playing like a quarterback.

It's video game football at its finest. Totally unrealistic at its worst. But would it work?

"It’s gonna take a program, coach, organization to say, 'We can make a commitment to running this as part of our offense,'" Rodriguez says. "Limited package deal -- get a QB that can be a true threat. To me, those guys that can play, Denard or somebody like that, he’s going to help in other ways, too."

"I definitely think there could be more of a role for that, if only in spot duty," says Chris Brown, creator of smartfootball.com and author of The Essential Smart Football. "People joke about the wildcat -- the problem with that is that people talked incoherently about what it was. The theory was sound: Fakes, multiple directions ... it puts a lot of pressure on the defense."

Creating pressure for the defense would be the greatest reward here. Not only are you talking about two potential ballcarriers, but also two potential passers, plus three to four pass-catchers. And that's before we even take into account all the different formations and blocking schemes that could be put into practice.

In order to pull this off effectively, teams would have to find, at minimum, two players capable of carrying the football and throwing it confidently against NFL-level defenses. Those players would be a team's best ... and would be at risk each snap.

"If you pay a QB $10 million, you don't want him to run the ball," Herm Edwards told SI.com. "Even Tim Tebow, they beat him up -- he was beat up at the end [of the 2011 season]. And he's big, he's 250 pounds."

Despite Tebow's success with the zone-read last year, NFL defenses -- now more than ever thanks to hybrid safety/linebackers and more athletic defensive linemen -- are still generally considered too fast for players to outrun them. Rodriguez likes to teach his quarterbacks to make their reads starting with the deep safety and working down. But Rodriguez's teams don't see safeties the likes of Troy Polamalu or Ed Reed.

"The difference is the speed," Rodriguez says. "The windows you can throw in in the NFL are a lot smaller than in college."

In this case, the drawbacks may outweigh the potential rewards.

Revisiting the pistol

In a classic episode of The Simpsons, brunch is described as "not quite breakfast ... not quite lunch, but it comes with a slice of cantaloupe at the end."

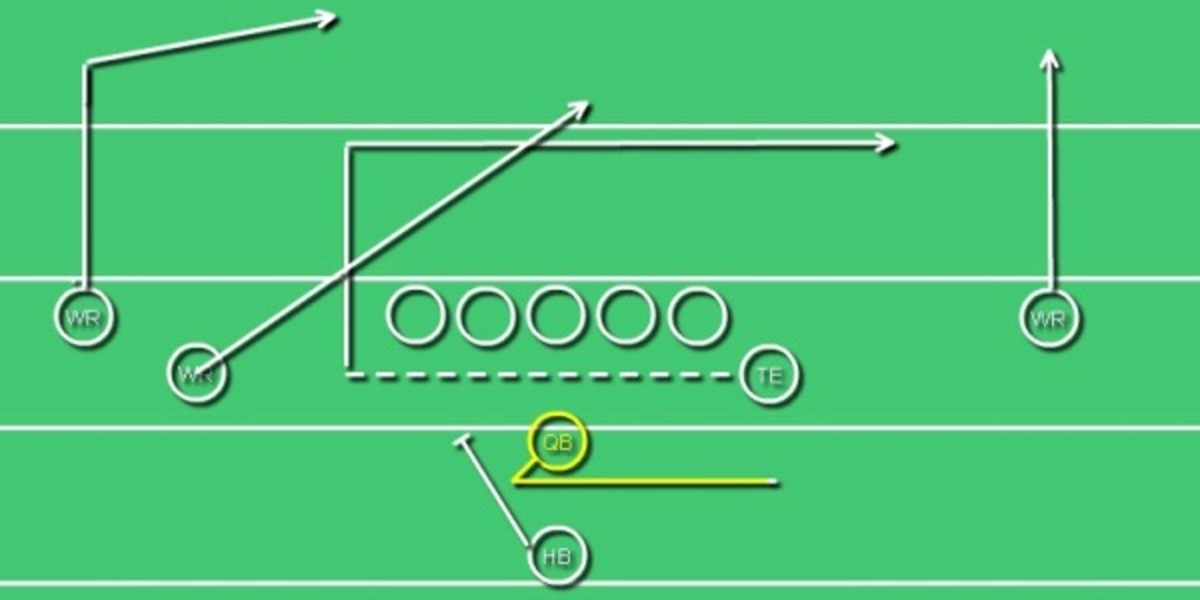

The pistol offense fits a similar bill (sans the cantaloupe): It's not quite the shotgun and it's not quite a traditional under-center, single-back formation. Instead, the quarterback lines up a few yards back of the center and a running back three or four yards behind him.

There are, as with any offense, a wide spectrum of variations available. Almost all of them provide the two biggest bonuses that a pistol attack can deliver: The quarterback can get a better read of the defense by stepping off the line, while the running back still gets the opportunity to run downhill.

When Tyler Thigpen and the Chiefs rather suddenly broke out the pistol in 2008, it sparked a dormant offense -- thanks in no small part to the extra room it created for RB Larry Johnson.

"[Running backs] want to run downhill," said Thigpen. "If they're beside you [in a shotgun], they have to run sideways. It was an opportunity for us to be able to put [Johnson] in a better spot."

Current 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick ran the pistol extensively at Nevada. The photo below provides another quick glimpse of the formation, with Nevada using trips left.

You should be able to get a sense for the positioning in the backfield: Kaepernick is four yards deep with his back four yards behind him. The back definitely gets to run downhill, though a downside is that he has to cover eight yards before he gets to the line -- a serious issue if the defense creates some push up front.

An end zone view of Indiana's pistol formation from a couple of years ago gives you a better idea of why teams like this offense anyway:

That's a run-heavy set with a balanced line (two linemen plus a tight end on each side of the center), so the defense cannot really cheat one direction or the other. If it does or if defenders crash hard toward the back, play-action passes can be deadly:

The pistol even brings the triple option to the table, courtesy of a fullback joining the backfield or a receiver motioning back:

"It's something for the coach, something opposing teams have to practice for," Thigpen said of the pistol. "You can do different things out of it ... and you can run an entire offense out of it as well."

Of course, if it were a flawless offense, it would have a permanent home in the NFL already, as well as a wider hold on the college game. The pistol is a challenge for the quarterback -- he must be able to run well; handle option plays; and adjust to a three-step release on his passes, instead of a five- or seven-step or a traditional shotgun.

And the pistol can be susceptible to the blitz -- a major issue against aggressive NFL defenses -- because of the running back's position, deep in the backfield and directly behind the QB, putting him at a disadvantage picking up blocks.

"It was tougher for the back, because he can't even see the ball snapped," Thigpen said. "It's definitely harder in that aspect."

Thigpen added, though, that protection schemes up front are not any different than if a team is in shotgun -- something every NFL squad is familiar with these days. The pistol is rarely used in football's upper echelon, and yet it might have enough of an upside to give it a future in the NFL.

Kicking it old school

There's a fantasy sports draft strategy known as picking against a run. In other words, if a bunch of running backs come off the board right before your pick, you'd take a wide receiver. Basically, you're bucking a trend to find value.

Think about how NFL defenses have evolved in recent years -- think about the offenses discussed above: Everything has trended recently toward faster, more agile playmakers on the defensive side of the ball. Guys who can stay with tight ends down the middle of the field and chase down quarterbacks.

So, what if a team attempted to take advantage of that by doing a complete 180 from the spread-heavy momentum of NFL offenses?

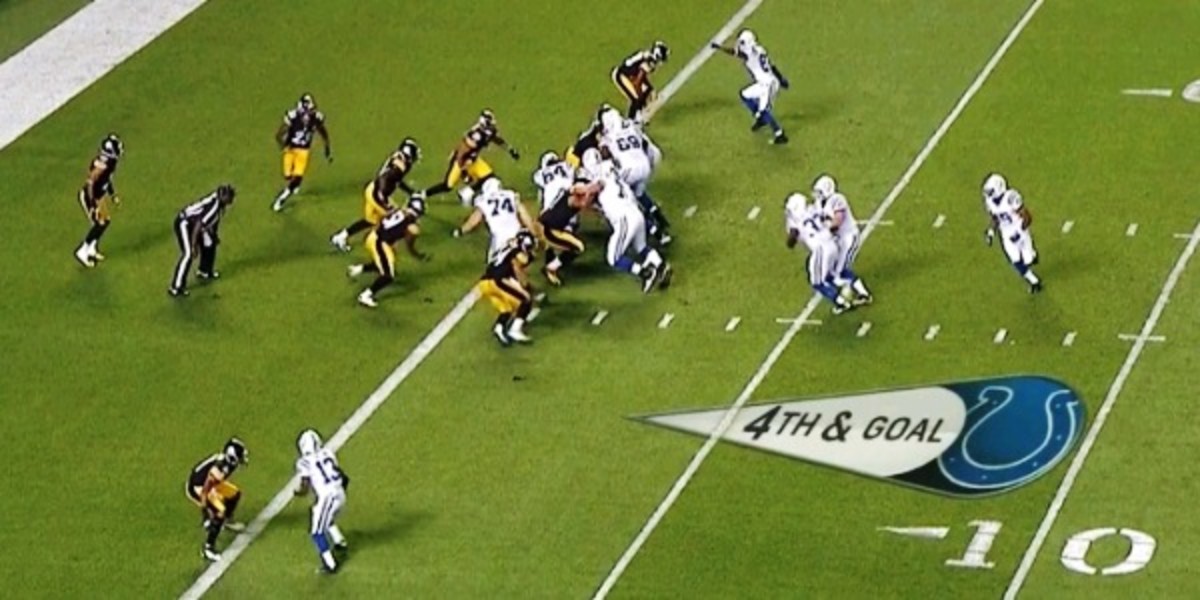

Andrew Luck's lone rushing touchdown as an Indianapolis Colt thus far came on a 4th-and-1 in the second week of the preseason. The Colts caught just about everyone off-guard by calling a triple-option.

Indianapolis started in a typical shotgun formation -- three receivers, one tight end and a running back. Just prior to the snap, the Colts motioned a wide receiver into the backfield. Luck faked a handoff up the middle, then ran an option left with his receiver.

This play is as old as time, but it works: The Steelers collapsed to the middle of the field, allowing Luck and his motioning receiver to sprint outside. Luck kept the ball and scored a touchdown.

The triple-option often brings to mind teams like Air Force, Army and Navy -- all of which run it at the FBS level. Georgia Tech has turned to it as well in recent years under Paul Johnson. The majority of those operate out of a flexbone formation, as opposed to the shotgun look that the Colts gave, but the principles are the same. And if the triple-option attack works as a base offense in college (Johnson is 43-22 with a conference title in four years at Georgia Tech), could some team bring it fully to the next level?

"I think almost anything can be useful," Brown said. "It is tough to defend -- the biggest difference in the NFL is there are no Navys or Air Forces or Armys. Yes, there are teams that are bad, but in theory, you’re only a couple of players or years away from being a contender -- whereas Navy knows that eight or nine of the games on its schedule are going to be a challenge."

That's not meant to undersell any of those schools, but the college version of the triple-option provides a couple of benefits: 1. It helps to negate talent gaps because of the efficiency with which it can be run; and 2. It give opponents headaches in preparation, since very few teams in the country run it. Those advantages could be diminished in the NFL -- mainly because of the level of defensive talent. Even a triple-option run to perfection might still have to deal with eight or nine elite defenders crammed into the box, with the sole purpose of taking away the run.

"The limiting factor," Brown said, "is you have to be able to throw."

Passing can be a huge challenge simply because of the extended time quarterbacks need to run through play-actions and drop deep enough to throw the ball. And, like the zone-read attack, the triple-option also exposes a team's quarterback to repeated and brutal hits.

But as Luck and the Colts (and several other teams, including Cam Newton's Panthers and Tebow's Broncos last year) showed, the triple-option can be a weapon -- maybe not as an every-down call or with a base flexbone/wishbone formation, but certainly as a change of pace.

Changes within the norm

It's not just formational shifts that might occur in the near future, but rather fundamental changes within current offenses. Brown addressed one such change in a recent post for Grantland, subtitled "How modern offenses are rethinking the most fundamental elements of football 'plays.' "

In that post, Brown examined how the 2011 Packers implemented an approach that Oklahoma State had used to great success with Brandon Weeden at quarterback: packaging plays. In short, offensive coordinators are now beginning to give their quarterbacks both a run and a pass play for each snap. Without simplifying it too much, the quarterback essentially inherits the same responsibilities he would on a zone-read -- basing his post-snap decision off one particular defensive player (usually a linebacker). Here, rather than opting to hand off or keep the ball, the quarterback must choose between a pass or run, based on what coverage that keyed defender shows.

The other tweak currently en vogue is increased tempo. We've seen this in the extreme at the college level. Oregon, for example, ran 72.5 plays per game during its 14-game 2011 season. That's nearly nine plays per game higher than the NFL average (63.6) and almost three per game better than the NFL's most up-tempo team, New England (69.8).

Those numbers may not sound overly significant, but nine extra plays a game means nine more chances to hit a home run. It also means nine extra snaps of rest for your defense and a greater edge in ball control. Oregon does its work on the ground via the zone-read -- a stark contrast to the run-and-shoot, which operates at a quick tempo but could backfire into brutally short possessions.

"Somebody’s gonna do it," Rodriguez says when asked if the rapid-fire approach could make it to the NFL. "And someone's gonna do it at a faster tempo."

******

"I don’t know if I have some real triumphant answer about where it’s all going," Brown says. "The game today looks a lot different than where it was in 2002 ... I don’t know what it'll look like in 2022."

"Tell you what, it's arena football," says Edwards, who played defensive back in the NFL before becoming a coach. "It's almost not fair at this point. ... Football advances, and when it advances to where it's at now, you shake your head."

But just as it looked last season like offenses had taken over the league completely, the Giants reeled off a Super Bowl run that would not have happened without a dominant front four and a pass rush that helped keep Green Bay and New England in check.

All that can be said for sure is this: Offensive coaches will continue to search for anything that gives them an edge. And defensive coaches will work long and hard to neutralize those advancements.

Maybe some team turns it loose with a two-QB system. Maybe the triple-option makes a resurgence in the NFL or the pistol becomes the new shotgun.