Weight presents double-edged sword for linemen prospects

There were many fine performances at Alabama's pro day on March 13 in Tuscaloosa, but none so intense, so all-in, so loud as the effort put forth by Scott Cochran, the Crimson Tide strength coach whose Klaxon voice provided a frenetic, urgent sound track to the proceedings.

Make today count! Finish stronger! Speed! Speed! Speed! SPEED!

Cochran could moonlight as an announcer at monster truck rallies, yet even this chronic extrovert fell silent after Chance Warmack took his second turn at the vertical jump. With scouts and coaches from all 32 NFL teams watching, the 6-foot-2, 317-pound guard exploded from his stance ... and was immediately snatched back to Earth as if by some invisible bungee cord. It was the least impressive vertical leap of the day. And yet scouts could not have cared less.

Teams don't need Warmack to dunk basketballs. They need him to be a road grader in the running game, a bridge abutment anchoring the pocket. He is a brute with a high football IQ, a technically proficient mauler with strong hands and sweet feet. And for that he could go higher in the draft than any guard since 1997, when the Saints took Chris Naeole 10th out of Colorado.

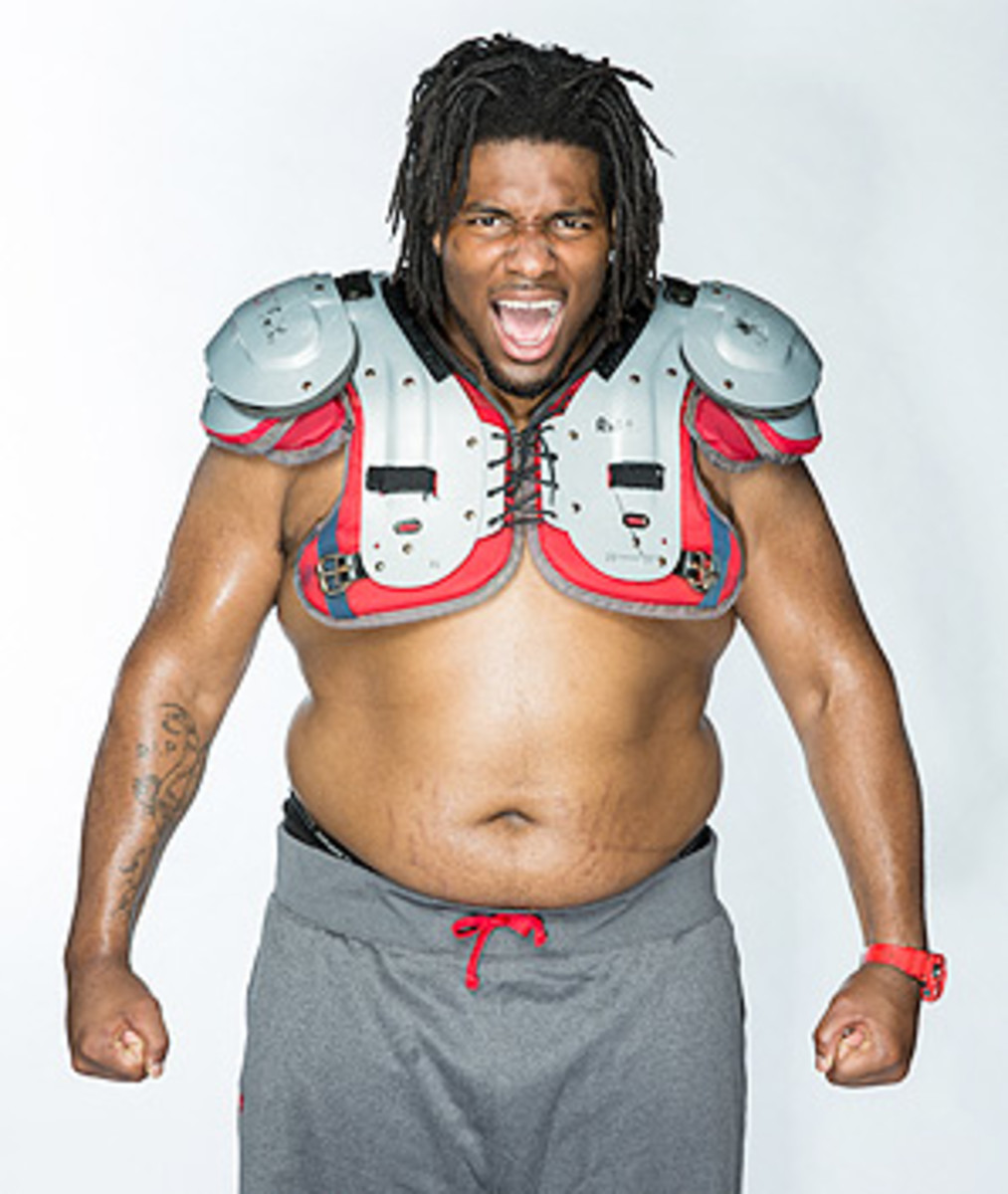

Warmack was one of a handful of prospective offensive and defensive linemen who agreed to pose shirtless for SI, revealing the raw clay from which tomorrow's All-Pros will be sculpted. And while a few looked conventionally athletic, most carried various layers of fat: over pectorals devoid of definition; around doughy midsections and pachyderm-like posteriors. Photographed at various states of preparation for the NFL combine and pro days, some could just as easily have been girding themselves for hibernation.

That's neither new nor surprising. Standards of beauty vary from epoch to epoch, profession to profession. The plump models painted by Rubens during the early 17th century look nothing like the bodies seen, for instance, in SI's Swimsuit Issue. Likewise, most offensive line coaches can see the beauty in a Buddha belly jiggling over tree-trunk legs, and a backside the size of a backhoe.

"Your power comes from your hips and your ass, that's where your biggest muscles are," says one of those admirers, Joe Pendry, an O-line coach for 45 years in the NFL and in college, including Bama's 2009 championship season. "That's your power pack. Some guys got a gut sticking out over top of that, but they can still use the power pack. They can get the job done for 16 weeks."

But just how big is too big? Where does piling on the pounds reach a point of diminishing returns? LeCharles Bentley, twice a Pro Bowl lineman with the Saints in the 2000s, believes there are plenty of porkers who have eaten their way well past that mile marker. Bentley, who runs an academy for offensive linemen in Avon, Ohio, warns against "almost an epidemic of obesity" in the NFL. "A lot of the bodies you see in the league are soft. You don't have to look like a receiver to play offensive line. But it's critical to have correct body composition. You're not playing to your full athletic potential when you're that fat."

***

Thick and wide and blockish though he may be, Warmack doesn't fall into Bentley's danger zone. Indeed, beneath a layer of blubber, actual abdominal striations are visible. "I saw him with his shirt off at the combine, and he's kind of got a six-pack," says Larry Warford, a 6-3, 332-pound guard from Kentucky whose abdominal musculature is more comprehensively concealed. "I asked him, 'Why do you have a six-pack? How is that fair?'?"

Warmack was a 300-pound ninth-grader who "skyrocketed" -- his word -- to 345 by his senior season at Westlake (Ga.) High. At Alabama, coaches told him to drop 35 pounds. After many early mornings of "fat boy camp" under the barked supervision of strength coach Cochran, he got there.

But at what price? Taking the field at a sylph-like 310 pounds, Warmack wasn't his usual mauling self. "I wasn't feeling it," he says. "And I played like I wasn't feeling it." He'd gained a leaner state, but lost his mojo, so he and Cochran compromised: He could play at 329, but no heavier.

Warmack freely admits that his February and March weight -- 319 -- is temporary. He dipped into the teens to perform such tasks as the 40-yard dash, three-cone drill and shuttle runs. (About that vertical leap then.?...) By training camp in July he'll be crowding 330. "Right now," he said at pro day, "if I had to block a 370-pound nosetackle, I couldn't do it as efficiently as if I was 328."

But seriously, Chance, even in this age of shed-sized down linemen, who weighs 370?

"It was just a certain situation that led me to 370," Georgia's John Jenkins told a group of reporters at the combine. "But I'm more like a 340-or-below guy."

Jenkins, who aspires to play like Patriots defensive tackle Vince Wilfork (who tips the scales at a twiggy 325), took the field for December's SEC title game against Alabama at 370. While stamina becomes an issue for anyone weighing closer to 400 than 300, he had enough to blow by Warmack for a second-quarter sack. By the time the combine rolled around, Jenkins was down to 346.

How had his weight spiked to begin with? Jenkins explained that he'd lacked "the right knowledge" about diet and nutrition. Armed with that info and a blender, he had the situation in hand. Upon rising each morning at 6 to work out, he said, "I have a protein shake. After the workout I have another shake. I eat something light around 10," he continued, not specifying what he meant by "light" -- a salad? a roast goat? -- "then another shake. Then something small. It's all about the portion [size]." Most of his shakes are berry-based: "No pineapple or anything like that." Those are mixed with a scoop of protein powder. "Instead of milk I use ice and make [the shake] real thick. The thicker the shake, the fuller you feel."

Sylvester Williams also weighed 370 when he walked on at Coffeyville (Kans.) Community College four years ago. He'd started just one game in his single season at Jefferson City (Mo.) High, then assembled radiator parts for 18-wheelers before deciding that he wasn't done with football. By Coffeyville's opening game the defensive tackle known as Sly was down to 313 -- his current weight -- and starting. Two years later, having earned a full ride to North Carolina, he was plaguing ACC linemen with his surprising quickness and killer swim move.

As is the case with many big men, Williams' weight has been more of a sine wave than a straight line. It had crept into the high 330s after the 2011 season, when he met the Tar Heels' new coach, Larry Fedora, who politely informed him: You need to lose some weight. Sly obliged.

NFL personnel types must now ponder what will happen to the bodies of Warford and Jenkins and Williams once they get paid. It's happened before: Throw guaranteed money at a guy, and the next thing you know he's drinking smoothies with pineapple and whole milk.

***

"When it comes to protein," Bob Calvin says, "we tell our guys, The fewer legs, the better." Calvin is a nutritionist for Athletes Performance, the industry leader in getting collegians ready for the combine and pro day. Chicken [two legs] is preferable to red meat [four legs]. "And fish is preferable to chicken."

Since opening its doors in 1999, Athletes Performance has trained six No. 1 picks. Fourteen of last year's 32 first-round selections retained the outfit's services. This year Calvin worked with 6-5, 306-pound Terron (Terronnosaurus Rex) Armstead, who was a little-known tackle out of Arkansas Pine-Bluff until he ran the 40 at the combine. Armstead's time of 4.71 seconds -- .01 faster than Oklahoma tackle Lane Johnson's -- set a combine record for offensive linemen. Between his performance in Indianapolis and solid showings at the Senior Bowl and East-West Shrine Game he is, as NFL Network draft guru Mike Mayock describes him, "the quickest-ascending player in this draft," vaulting from a late pick to a probable second-rounder.

To Mayock, reports of an obesity epidemic are greatly exaggerated. "Offensive linemen this year look much different than they did 10 or even five years ago," he says, meaning they look better -- leaner, not as sloppy as in past years. He attributes that, in part, to combine prep academies: "For a lot of these [prospects], for the first time in their lives people are hammering on them about nutrition."

Among those who seemed to have listened is a trio of athletic left tackles who will likely be drafted among the first 15 picks. Best known among them is Texas A&M's Luke -Joeckel, who protected the blind sides of drop-back passer Ryan Tannehill (2010 and '11), and, last season, quicksilver scrambler Johnny Manziel. The 6-6, 306-pound Joeckel is blessed with Pendry's power pack, but for the odds-on favorite to be taken first, his upper-body is surprisingly ... ordinary. Slightly more yoked is Eric Fisher, a 6-7 306-pounder out of Central Michigan who is making a late push to supplant Joeckel at No. 1. After laboring in semiobscurity in the MAC, Fisher graded out as the top prospect in the Senior Bowl. And less polished than Joeckel or Fisher, but sharing their steep upside, is Johnson, a high school QB who played tight end and defensive end for the Sooners before moving to tackle two years ago. Johnson made a pile of money at the combine, deflecting attention from his lack of experience with a series of jaw-dropping efforts, recounted here by Mayock: "He ran 4.72 in the 40 -- at 303 pounds. That's as fast as [49ers">49ers wideout] Anquan Boldin ran. He jumped 34 inches, which is [a half inch less than Bengals wide receiver] A.J. Green jumped. And he broad-jumped 9-10, which is what [Patriots running back] Stevan Ridley jumped. That's the freakiest combine ever."

More of the tackles coming into the league -- sub-325 guys like Tennessee's Dallas Thomas, Louisiana Tech's Jordan Mills and Florida's Xavier Nixon, each projected to go in the first six rounds -- are better conditioned. As products of historically up-tempo or spread offenses, they've had to be. While that may answer questions about their fitness, it raises others about their readiness to get in a three-point stance and fire out in the run game.

Products of spread systems, accustomed to operating out of a two-point stance in 2012, face a rocky transition, according to Phil Savage, former GM of the Browns and now a scout for the Eagles. Blocking schemes in spread systems tend to be "more simplistic" than in the pros, he says, and linemen making the switch will be challenged by exotic packages. Bentley says these linemen aren't required "to play the game technically. They're asked to get in the way, and then we'll let our quarterback -- who runs a 4.4 -- work his zone-read magic."

It's a tough transition, says Savage, "but the good ones figure it out." And the good ones aren't always the ones who look like they'd be the good ones.

***

Savage acquired Bentley from the Saints in 2006. But when Bentley blew his knee out in Browns training camp, Savage made a deal with the Eagles for Hank Fraley, a five-year vet out of Robert Morris. "He had the worst body," Savage recalls, "but he knew how to play. If he saw that there was confusion over a substitution, and we were going to be penalized [for too many men in a huddle], he'd get out of the huddle until we got it sorted out. That's how aware he was.

"Hank was certainly nothing to look at, but he was smart, and he played with leverage, and knew where his help was. He was a bad-body player who ended up having a nice career."

Take heart, pear-shaped prospects! Or, as Howard Mudd puts it, "It's not about what you look like on the beach." Mudd played seven NFL seasons, then coached offensive linemen for another 38. "I had a guy in Indianapolis by the name of Tarik Glenn," he remembers. "Bad-looking body. His legs were short and shaped kind of funny. He looked a little like Charlie Chaplin." But he earned three trips to the Pro Bowl while protecting Peyton Manning's blind side.

Mudd, who retired in December, tended to take combine feats with a grain of salt. He wasn't looking for a number -- five-flat 40, 33 reps on the bench. Asked what he was looking for, he comes back to "balance ... and recovery."

Why recovery? Plays seldom unspool the way they're drawn up on the greaseboard, and in the controlled chaos of the trenches, one of the most important traits for a lineman to have, he says, "is the ability to right yourself from an awkward position.

"When I looked at college players, I wasn't so interested in the times they'd knock a guy back five yards. That doesn't happen very often. I wanted to see what happens when he starts to block a guy, but the guy gets away from him, and he almost falls down, and yet he's able to right himself and complete the play. It might not even look that good, but I'll say, Wow. That guy recovered."

After tearing the patellar tendon in his left knee in 2006, Bentley faced the rehab from hell. He needed four more surgeries, the final three to excise a staph infection eating away at the tendon. At one point doctors were close to amputating his leg. He nearly died. Of lesser importance he never played another snap in the NFL.

"I learned so much about football when I couldn't play," he says. "I learned how the body works when my body no longer worked. I'm out of the league, but I've held on to my passion to make sure this game is played the right way."

He has some strong opinions about what constitutes the right way. One of them: You don't do the game -- or yourself -- any favors by waddling around out there like a sumo wrestler. The problem, Bentley believes, is a flawed mind-set that can begin in high school.

"Say you have a lineman, maybe he's 6-2, 190," he posits. "And the first thing he hears from his coach is, 'You gotta get bigger.' Telling that to a 15- or 16-year-old kid, you might as well tell him to eat all the fast food he can get his hands on."

So the weight he gains isn't quality weight, "and now that player is in a downward spiral. He gets so big that he doesn't understand how his body is supposed to move and work from a mechanical point of view. He's not learning how to play offensive line. He's stuck in this constant mind-set of, I've gotta be big."

Some youngsters don't have a choice. Warmack was a 300-pounder in ninth grade, yet he doesn't remember being self-conscious. "I've always been comfortable in my own skin," he says. He tells fellow big guys and gals, "Don't be ashamed. God made you this way for a reason. Embrace it. Celebrate it."

Celebrate it like Warmack, who, upon completing his drills at the combine was asked about his dinner plans.

"White Castle," came the reply.

And how many burgers did he intend to put away? An even dozen. But don't worry. They're small.