Colin Kaepernick Does Not Care What You Think About His Tattoos

TURLOCK, Calif. — On a hot May night in California’s Central Valley, graduation night at Pitman High, eight police officers stand in a multipurpose room listening to instructions. One is an undercover cop. A couple are SWAT-teamers in bulletproof vests. Something very big is fixing to happen.

The officers are given their assignments by veteran detective Jason Tosta—they’re told to make sure that no one rushes the stage and that the guest speaker enters and exits without being mobbed. “This was supposed to be a secret,” says Tosta, “but now it’s all over Facebook and Twitter, so I’m sure some people know he’ll be here.” The detail is told there was lax security at a grocery store appearance recently; people were pushing over displays to get to the guest, who had to make a hustling exit to escape the fray—only to be followed by three cars after he left.

Then Colin Kaepernick, quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers, walks in, accompanied by his parents, Rick and Teresa. Pleasantries are exchanged. Colin, Pitman Class of 2006, hugs a few of his former teachers. Pictures are taken. The cops brief him on what’s about to happen.

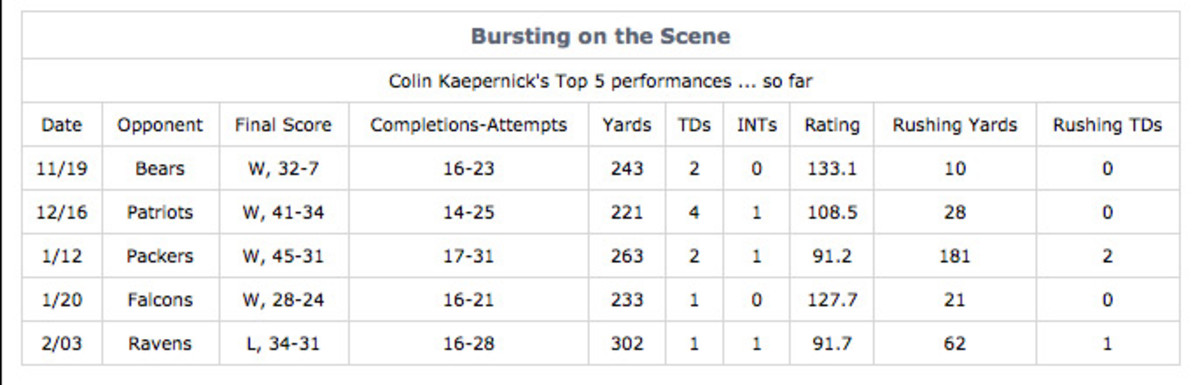

In a moment of downtime before Kaepernick takes the stage, a couple of the officers have a chance to engage with him. Do they ask him what it was like to start in the Super Bowl, seven years after he took a photography class in the room right across the hall? How it felt to set an NFL record for rushing yards by a quarterback in a game—in the playoffs, no less? Whether he’s daunted by following in the footsteps of Joe Montana and Steve Young?

No. They want to talk body art.

“Love your tattoos,” Tosta, 42, tells Kaepernick. “I’ve got my family history running down my left arm. My mom had to have a heart transplant, so I’ve got a hand holding a human heart.”

Kaepernick tells them about his post-Super Bowl tattoos. He had massive Polynesian tribal symbols done on both pecs, so that his upper torso is covered in a rubric inscrutable to most of us. “They represent family, inner strength, humility and spiritual growth,” Kaepernick says of the images. He had the work done in San Jose three nights after the Super Bowl, sitting for six hours until it was finished at 2:30 a.m. The officers are at rapt attention.

New world out there. New quarterback for it.

Adopted. Biracial. Supremely tatted. A runner sometimes. A thrower sometimes. Colin Kaepernick, age 25, is the anti-Manning, and he likes that. A lot.

Not that Kaepernick—who played his college ball at Nevada, the only school to offer him a ride—has anything against the quarterbacks with the classic big-school football pedigree: Tom Brady, Peyton and Eli Manning, Aaron Rodgers, Matthew Stafford, Matt Ryan. But none of those quarterbacks was adopted at the age of six weeks. None had friends questioning whether he was white or black. None is being pursued by a birth mom he’s not interested in knowing. None, apparently, has the same yearning to have 70% percent of his upper body covered in ink. None has rushed for 181 yards in an NFL playoff game. For none did his 10th NFL start come in the Super Bowl.

Now, after paying tribute to his retiring former football coach, after stopping to pick up pepperoni pizza at Little Caesars, and after dropping his mom and dad off at their house in Modesto, Kaepernick is in the back seat of an SUV, heading to his home near the 49ers’ training facility in Santa Clara. It’s past 10 p.m., pitch-black outside on California 99, and the 90 miles or so to cover means there’s plenty of time for Kaepernick to talk frankly about himself and his place in the NFL. At the Super Bowl, when the world was trying to get to know him, he gave brief, vanilla responses in his press conferences; his longest answer might have been about 14 words. Now, he’s got a lot more to say:

“I want to try to break that perfect football mold. I don’t want to be someone who can be put into a category. I want to be my own person. I want my own style. I want to be someone who can’t really be compared to anybody.

“And I want to have a positive influence as much as I can. I’ve had people write me because of my tattoos. I’ve had people write me because of adoption. I’ve had people write me because they’re biracial. I’ve had people write me because their kids have heart defects—my mom had two boys who died of heart defects, which ultimately brought about my adoption. So, to me, the more people you can touch, the more people you can influence in a positive way or inspire, the better.”

Great players can touch more people, and Kaepernick knows that half an NFL season does not make him a great player. But today’s game sets up nicely for a quarterback with his tools: fast feet and a powerful arm. The movement toward a new style of quarterback is here. Pete Carroll, the Seahawks’ coach, told me in January that the spate of young, mobile QBs “is the evolution of football—screaming at us.” Ohio State coach Urban Meyer said of Kaepernick: “I mean, Wow! He’s running 60 yards untouched? When was the last time you saw a quarterback run untouched in the NFL for 60 yards? People said, ‘You can’t do that in the NFL!’ Yes you can.”

During the ride back to the Bay Area, Kaepernick is enlightening when talking about the final, frustrating drive of the Super Bowl, the series he keeps playing over in his head. But it’s all the other stuff that makes him a compelling protagonist in the world of football, and in the larger, more complicated world beyond sports.

ADOPTION

Kaepernick was born in Milwaukee in November 1987 to a tall, athletic 19-year-old woman named Heidi Russo. She is white; the father, whom Russo has never identified, was African-American. A month after Colin’s birth, Russo gave the baby up to a young couple from Fond du Lac, Wisc., Teresa and Rick Kaepernick, who’d lost two infant boys to heart disease and were pining for a son to join their two other children, son Kyle and daughter Devon.

For a while Teresa sent Russo photos of Colin as he grew, but it took such an emotional toll on Russo that, she has said, she asked Teresa to stop. Russo, in interviews over the past year, has said she wants to meet Colin and has reached out to him through social media, trying to arrange a meeting. He has declined, saying he feels he knows his parents.

“Do you feel you’ve drawn the line with her, and you just don’t want to meet?” I ask him.

“I feel like I have drawn that line,” Colin says. “I feel like it’s been drawn for a while. The way things transpired at the end of the season and this offseason, that line just became darker. That’s not going to happen. It’s not something I want to do. Ultimately I know who my family is, and I know who my mother is.”

Colin already wasn’t inclined to have a relationship with his birth mother. He called it a personal decision. And he’s been put off further by what he thinks is Russo’s aggressiveness in trying to make it happen.

“People asked me to do interviews on it,” he says, “and they asked my family to do interviews on it, and we turned them down and said, ‘It’s not a story. In the future, if I have a change of heart and I want to meet her, then it will happen.’ The same interviews we turned down, she did. I felt like that was disrespectful to me, my family and especially my mother. I feel like if I go down that road now, I’m disrespecting my mother as well, and that’s not something I’m willing to do. I know my mom would never tell me not to go meet her; she would help me do it if I wanted to. But in my mind, that’s just not something I’m willing to do.”

Kaepernick makes it clear he’s “very grateful, very happy” Russo gave him up for adoption. “But past that,” he says, “she wasn’t the one who was taking me to football practice, she wasn’t working 12-hour night shifts so she could be with me when I went to school and got home. I think people see what my birth mom did and say, ‘Well, that was great, what she did for you. You should go see her and give her that recognition and be happy for what she did for you.’ I don’t think people realize the sacrifices my mother [Teresa Kaepernick] has made and what she has done for me, and what she has been through in her life to help me to get to where I am now.”

In the middle of Super Bowl week, ESPN’s Rick Reilly wrote a column headlined “A Call Kaepernick Should Make” that angered the Kaepernicks. Reilly has an adopted Korean daughter, Rae, who with the support of her adoptive family returned to South Korea to meet her birth mother. Reilly wrote about how healthy and healing he thought it would be for Colin to reach out to Heidi Russo and for the two to meet. “You can’t imagine what it would mean,” Reilly wrote.

“I know exactly what column you’re talking about because someone sent it to me,” Colin says. “He referenced his situation with his daughter. My first instinct was, Well, number one, it’s none of your business what my decision is, and number two, just because your situation worked out doesn’t mean it will work out like that for everybody else. The fact that he said [the meeting] brought closure to his daughter and she feels better about it now .... To me, there’s no closure to be had. There’s no benefit from it.”

It’s a strange situation. Kaepernick wants to tell the world, “This is a private matter. Leave me alone.” But the game is public, and the media covering pro football is as intensely interested in the people who play the game as it is in the game itself. The bigger Kaepernick gets, the more intense that interest will be. How will he deal with it as his football star grows?

RACE

Kaepernick says his biracial makeup was never a big deal in his formative years in Turlock, mostly because his parents were open with him about it. “They were honest with me from the moment they had me. My parents always told me we could talk about it anytime I wanted to. I never really completely understood what it meant when I was young. To me, they were my family. I don’t remember how old I was. But I said to her one day, ‘Why is my skin darker than yours? I don’t really look the same as you.’

“She told me, ‘It’s because you’re adopted, but I wish I had pretty brown skin like you.’

“I never really thought much about it. Kids would say things sometimes, but my family just always loved me. That was the important thing to me.”

TATTOOS

Another column, by David Whitley of the Sporting News, made the Kaepernick family hot too. “Kaepernick is going to be a big-time NFL quarterback,” Whitley wrote in late November. “That must make the guys in San Quentin happy.” Quarterbacks, Whitley reasoned, are team CEOs, “and you don’t want your CEO to look like he just got paroled.”

“My mom has always been so-so with tattoos,” Kaepernick says. “Like, ‘When are you going to stop? Please don’t get any more.’ As soon as that article came out, she did a complete flip. She was like, ‘How dare you judge my son for his tattoos! Do you even know what his tattoos mean? Do you know what they mean to him?’ ”

The SUV drives through the California night. No radio. Just Kaepernick on a roll.

“It blows my mind that people still think tattoos are just gang-related, or have negative connotations,” he says. “So many people have tattoos because their family’s been through something—you heard that police officer tonight—or it’s a situation they’ve been through that’s made them stronger, and they want to make sure they remember it forever. I don’t think people fully understand how deeply people believe in their tattoos.”

Kaepernick’s dad was like many American fathers who despise tattoos, telling his son, “While you live under my roof you’re not going to have a tattoo.” Many of us have said words to this effect to our own teens. So Colin waited until he got to Nevada to start getting a series of religious-themed tattoos. “My first one,” he said, “was Psalms 18:39.” The scroll coming down his right shoulder quotes the Bible verse: “You armed me with strength for battle; you humbled my adversaries before me.” Ever since, he says, “It’s been a constant working piece.

“To me it’s just another way to be different and try to separate myself as my own man. If I get judged for something like my tattoos, so be it. I was talking to a few of the Rams players [this offseason]. One of their defensive linemen told me, ‘I love the fact that you started kissing your tattoos because of someone writing an article, basically showing everybody that you have tattoos and you’re still a good person. I have tattoos and I get judged for them. You’re really helping me change the perspective of tattoos.’ ”

And on the seventh day, he plays quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers.

The last time we saw Kaepernick on the field, he was failing, and flailing. Super Bowl XLVII, 49ers’ ball at the Baltimore 5, third-and-goal. Game clock stopped at 1:55 in the fourth quarter. Ravens up 34-29.

“That’s the play I’d like to have back—the play we had to call timeout,” he says. “It was just a slow operation all the way through.”

Kaepernick, set back about five yards from center in the Pistol formation, had the Niners ready at the line with 11 seconds left on the play clock. He started barking signals in the deafening Superdome. With five seconds to go he stepped forward, apparently adjusting the protection because of what he saw in the Baltimore defense. With a couple of seconds left on the play clock, coach Jim Harbaugh scrambled over to the side judge, and just before the clock reached zero the Niners got a timeout.

The players, though, weren’t aware. The ball was snapped. Kaepernick took it and dropped back a step as running back Frank Gore darted left in front of him. Tight end Vernon Davis sealed off linebacker Terrell Suggs, who’d slanted inside from his spot on the right side of the defense. Gore and second tight end Delanie Walker blocked safety Bernard Pollard and could account for cornerback Cary Williams, at the goal line. One more Raven remained to be blocked: Ray Lewis. And here was right guard Alex Boone, pulling left, with Lewis in his sights. Colin Kaepernick, of the very new breed, versus Ray Lewis, of the old school, on what might very well have been the last play of Lewis’s career.

But the showdown didn’t happen. Kaepernick took two running steps toward the left flank before he realized the play had been blown dead.

Rewatch that dead play, and all you can do is dream about what might have been. The play-caller, offensive coordinator Greg Roman, told me last February, “Will it eat at me? Of course it will.” He isn’t alone.

Now it’s silent both inside and outside the SUV—even the normal road noise seems gone—as Kaepernick’s mind goes back to that play in February in New Orleans.

“I constantly think about it,” he says. “I replay it. I rehash it. What could I have done better? If I got everybody up and got them set quicker, we wouldn’t have had to worry about the play clock. The way the play looked to me, I don’t feel there was anybody that was going to stop us from getting in the end zone . . . It looked like it could have been a walk into the end zone.”

“You saw it the way I saw it?” I ask. “That there’s a good chance it could have been you against Ray Lewis for the Super Bowl?”

“Yeah, I mean ... There was a linebacker coming over the top—Ray—but I just don’t feel that was something that was going to matter.”

San Francisco didn’t want to run the same play after the timeout, so Kaepernick ended up throwing his second of three straight incompletions to Michael Crabtree. On fourth down Kaepernick felt pressure and threw too high and far for Crabtree—who wrestled with corner Jimmy Smith getting off the line and couldn’t get to the ball. It’s doubtful Crabtree would have had a chance at the pass anyway, but Kaepernick didn’t like that there was no penalty call against Smith. “I’m not going to comment on it, but you’re asking the question for a reason,” he says.

“How long,” I ask, “did it take you to get over the game?”

“Still not really over it,” he says ruefully. “It feels like something was stolen.”

But look at what Kaepernick accomplished last year. When Brady and the Patriots fought all the way back from a 31-3 deficit against the 49ers to tie the game at 31 on a rainy December Sunday night in Foxborough, Kaepernick responded. He faced down a zero blitz by New England and found Crabtree for the decisive touchdown in a 41-34 stunner. “What a surreal moment,” he says. “It was crazy, going to shake [Brady’s] hand after the game, knowing we’d just beaten a guy who’s going to go down as one of the greatest ever. I can’t even remember what I said, or what he said.”

By the time the playoffs began, no one knew quite what to expect from Kaepernick, who’d been running the crazy read-option maybe 20% or 30% of the time. Against the Packers in the divisional round, he kept the ball a lot, rushing 16 times for 181 yards. The NFL had been alive for 93 seasons, and no quarterback had rushed for that many yards in a game—ever. That game made Kaepernick realize what a crazy weapon his legs can be.

“It got to a point,” he says, “where we could hear [the Packers’ defenders] arguing while we were in our huddle. ‘You’re supposed to do this,’ or ‘You have to do this, then the other.’ At that point, our offense was like, It’s over. As soon as you start turning on your teammates, you’re not going to be productive. You know you have them in the palm of your hands.”

At Atlanta the next week, for the NFC title, Kaepernick ran the ball exactly once off the read-option . . . and got buried for a two-yard loss. His arm won that game. And in the Super Bowl, it pulled the Niners back after they’d fallen behind 28-6 in the third quarter.

Now? He’ll miss Crabtree, out for at least half the season with a torn right Achilles. He’ll need newcomer Anquan Boldin, stolen from Baltimore for a sixth-round pick, and last year’s first-rounder, A.J. Jenkins, to pick up the slack. “I’ve trained and thrown a lot with A.J. this offseason, and his progress is fantastic,” Kaepernick says. “Night and day from last year. And Anquan, he’s such a man. So glad to have him.” Roman trusts Kaepernick enough to have asked him his likes and dislikes this offseason, and he won’t have the challenge of Alex Smith—traded to Kansas City before the draft—to worry about. The 49ers are Kaepernick’s team, and they should be for years to come. Provided, of course, he doesn’t get KO’d running around too much.

In San Francisco’s final minicamp practice on June 13, before the team dispersed for its summer break, Kaepernick finished with five straight completions to five different receivers, taking the first-team offensive unit downfield crisply against the first-team defense.

“Colin,” said coach Jim Harbaugh, “he’s been on it all offseason.”

Flash back to Kaepernick’s appearance at Pitman High: Everything went smoothly—nothing out of the ordinary other than a few shrieks from graduates who were thrilled that the school’s most illustrious alum had returned to pay tribute to his retiring former coach, Brandon Harris. The coach was stunned to see Kaepernick. The two walked off the stage together, back into the multipurpose room, and shared a rib-breaking hug. Harris took in the scene, perfectly orchestrated by the cops and a 49ers PR aide, right down to the police escort that would get Kaepernick back on the road.

“This is amazing!” Harris said. “Colin has . . . he has handlers!”

Outside, his parents climbed into the back row of the SUV, and Colin sat in the middle row. Three motorcycle cops, sirens blaring, led the way out, zooming past the stopped traffic, through a red light and onto Highway 99.

“This is one serious escort,” Colin said.

“Anymore, we never know what to expect,” Rick Kaepernick added, shaking his head. “But we’re learning.”

A few quiet minutes later, rolling down the highway, Colin went back in time. He was no longer the 49ers quarterback. He was a boy again, a son.

“Mom? We got any food back at the house? I’m starved.”

Well, Teresa said, not really—not enough, anyway. So the SUV pulled into a Little Caesars, and Colin walked in to get a pepperoni pizza to go.

The kid behind the counter took the order, looked up . . . then looked up again before saying, “Whoa!” Kaepernick signed autographs for him and his pizza-maker, paid and thanked them both.

As Kaepernick walked out, another teen held the door for him—and didn’t have to do a double-take. It was Colin Kaepernick, in the flesh. Only one word came out of the kid’s mouth as Kaepernick walked by carrying his pizza box.

“Beast!”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com