The $2M Mistake

The MMQB’s Andrew Brandt will answer your questions in a regular mailbag. Send them through Twitter. Here, Andrew addresses the most common issues from the past week:

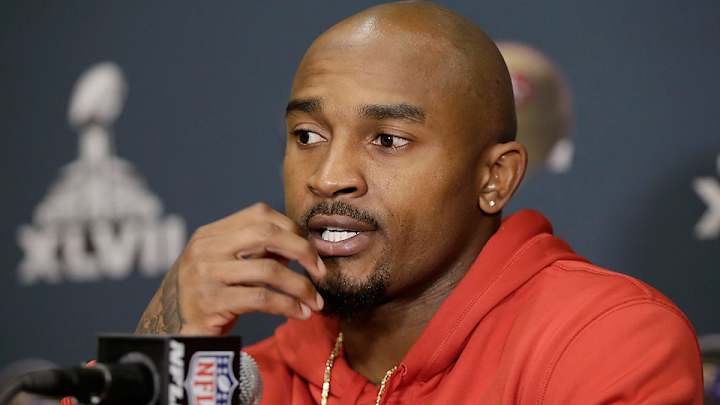

Q: What is your take on Tarell Brown losing $2 million for failing to show up for 49ers offseason workouts?

A: Something doesn’t feel right here, beyond the simple explanation of negligence by the agent. It’s easy—and justified—to pile on agent Brian Overstreet for failing to apprise Brown of his need to show up to team workouts to escalate his 2013 salary by $2 million, and Overstreet should bear considerable blame if that is in fact what happened. Certainly, as agent and client, they should have communicated at some point during the offseason about Brown’s non-attendance at workouts and the consequences of his absence. However, beyond conveniently throwing Overstreet under the bus, let’s look at the two other parties in this triangle.

I find it hard to believe that Brown was truly ignorant about a $2 million clause in his contract. In more than 20 years of dealing with professional athletes, as both an agent and a team executive, I learned the two things players talk most about are, in no specific order: 1) money and 2) women. Most players know exactly what they make, down to the dollar, and some even define themselves by those earnings. Now, as Brown enters the most important season of his career—his contract is up after 2013—he never thought to check into any financial reward or penalty regarding team workouts, something the vast majority of players choose to attend? Seriously?

And what about the 49ers? Coach Jim Harbaugh says he did not know about the clause. Although when I was a team executive I would not inform coaches about playing incentives, to avoid any appearance of impropriety in our playcalling or gameplanning, there was no similar need to insulate them from workout clauses. Whether Harbaugh knew or not, it is the job of other people in the organization to know. And a clause that alters cash and cap reserves by $2 million is one that teams not only know about but also keep a close eye on.

Did the 49ers owe the agent or player a heads-up on the $2 million? Technically, no. However, relationships between teams and their players' agents are important for future business dealings. The 49ers apparently felt that Overstreet, who only had one 49er as a client (now zero after Brown fired him), was not worthy of that kind of goodwill. If Brown’s agent had multiple players on the team, would the Niners have informed the agent about his client’s potential noncompliance? I think so.

My sense is there is more ahead for this unearned $2 million. The amount now becomes a convenient starting point toward an extension of Brown’s contract (or legal malpractice lawsuit). Stay tuned.

Q: What is “offset language” and why do teams care so much?

A: I will try to make this as simple as possible: Offset language allows a team to lessen its future liability if 1) it releases the player who has guaranteed money left on his contract, and 2) the player signs with a new team. The original team’s remaining obligation to the player is “offset” by the player’s salary from the second team.

Teams want these clauses—and are getting them—for several reasons, one of which is that general managers, coaches and contract negotiators all have offsets in their own contracts. Another important reason is so they can declare offset language to be “team policy” to agents and players, whether rookie or veteran, in future negotiations. Certain teams, such as the Jets with Mark Sanchez and the Eagles with Nnamdi Asomugha, have been burned by “no offset” guarantees and are adamant it will not happen again.

For instance, Asomugha, released by the Eagles in March with a $4 million “no offset” guarantee left on his deal, subsequently signed with the 49ers for a 2013 salary of $1 million. With no offset, Asomugha “double dips” and pockets the $4 million from the Eagles and $1 million from the 49ers. Had there been offset language, the Eagles’ remaining obligation to Asomugha would have been reduced by the value of his 49ers salary, to $3 million.

Q: When players like Jeremy Maclin and Dennis Pitta are injured and out for the season, are they always paid their salary?

A: Yes, although with a caveat. A team cannot release a player when he's injured; if it does it subjects itself to a potential grievance for salary due while the player was injured. In the case of high-caliber players such as Maclin and Pitta, they will clearly receive their full salary.

With players lower on the roster, however, the treatment might not be as simple. Many players have “split” contracts that pay the player a lower salary if he’s placed on injured reserve. Further, teams will “settle” with injured players who have no future with the team, negotiating a lump-sum payment based on the projected length of the injury, usually in the three-to-six-week range, and covering his rehabilitation costs wherever he goes. In other words, teams are paying this class of injured players to go away.