Forever in the Moment

SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y. — Bill Parcells is in his element: in the outdoors, on the patio of the lush Saratoga National Golf Club, with one of his best friends in the world, longtime NFL coach Dan Henning, sitting across from him. Henning waits for his 3:45 p.m. tee time. Parcells, recovering from left shoulder replacement surgery, won’t be joining his golf partner today. So he’ll slowly eat his soup, and he’ll nurse a monstrous iced tea, and he’ll reminisce.

He has a bit of a furrowed brow on this mid-July day.

“This the last time we’ll do one of these, you think?” he asks.

The last interview, he means, now that he’s going to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Saturday, the 22nd coach in Canton in the 94-year history of the league. The last time people might want to hear what he has to say.

“I hope not,” Parcells says.

* * *

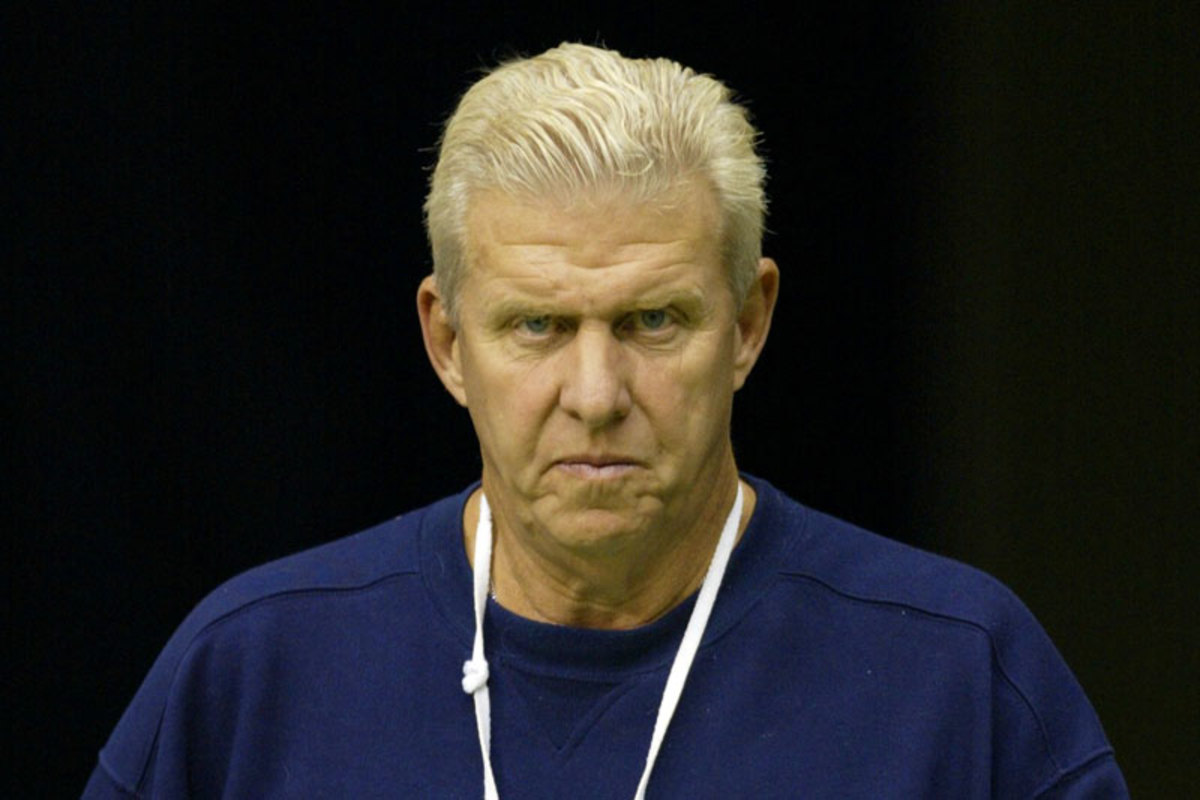

Parcells with Giants GM George Young (far left), and with a certain assistant who at the time preferred short shorts instead of a hoodie. (George Tiedemann/SI :: Jerry Pinkus/SI)

I covered Parcells’ Giants from 1985 to ’88 for Newsday, and in ’85 I moved from Cincinnati to New Jersey ahead of my family to report on training camp in Pleasantville, N.Y., about 40 minutes north of Manhattan. I would get to the media room early, maybe 7 a.m., to have coffee and just be around the coaches (Parcells, Bill Belichick, Romeo Crennel, Ron Erhardt, among them) and GM George Young as much as I could. It’s always been a competitive beat, but the setup was different back then. The lone coffee pot was in the media room, as were the New York papers, and the coaches, some of them baseball fans, would filter in to look over the box scores or read about whatever lurid thing was happening in the city.

Parcells was a regular around there. He was always taking everyone’s temperature, from the writers to his PR man and good friend Ed Croke, to the volunteers who worked the camp. One day he noticed me arriving early for the third or fourth time. “Who the hell are you?” he asked, and I told him, though I had introduced myself to him on the first day of camp. He shook his head, turned back to his paper and said, “Well, this game’s not for the well-adjusted.” That was the start of a conversation about something or other, I don’t recall exactly what. But it was the first of many conversations we’d have over the years—in hotel lobbies, including two pre-dawn talks at the Westin South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa, Calif., where the Giants stayed for Super Bowl XXI ... at baseball parks, including the one in Trenton, N.J., where he homered twice against Al Downing in American Legion ball ... in his car, on a Gandolfini-esque ride through his old Hasbrouck Heights, N.J., haunts not far from Giants Stadium ... and now here, to recollect the best memories from a life in coaching that stretches back to the Lyndon Johnson Administration.

Sit down with us as he shares them, starting with a lesson he learned six minutes into his coaching career, in the hamlet of Hastings, Neb.

Hastings College, 1964

Defensive coach

“Right out of college, at Wichita, I get hired to coach the defense at Hastings. We had to build lockers for the players before the season, and we had to do their wash after practice in cold water. Our training room had one taping table on it, and it was an old Coca-Cola can dispenser that the players sat on.

“The head coach’s name was Dean Pryor. I liked him a lot. He was one of my college coaches. So, now it’s the first day of practice. This is my first six minutes on the field as a coach—in my life! We don’t have any defensive coaches. It’s just me and the basketball coach, who is helping coach the football team. We’ve got this little nosetackle guy—we’re doing group agility—and he’s exhausted. I forget his name. So I’m doing the drills, the head coach is watching, and this kid is like—[Parcells is huffing and puffing]—‘I can’t go! I can’t go!’ I said, ‘Let’s go, let’s go!’

“Finally, the head coach sees it. Blows the whistle. ‘Everybody up!’

“I mean, practice has just started. Coach Pryor says, ‘Get that equipment off that man and give it to somebody that can go!’ Nobody knows what to do. Everybody just stands there. He says to the managers, ‘GET THAT EQUIPMENT OFF THAT GUY, I TOLD YOU TO GET IT OFF HIM! AND GIVE IT TO SOMEONE THAT CAN GO!’

“So they start undressing him right there. Sent him home—we never saw him again. Now, the equipment is lying in the field. Helmet, shoulder pads, all his pads. The coach says, ‘Don’t touch that equipment.’ He had them put a little fence around it. It stayed there the whole two-a-days. A little reminder. The reminder was, if you can’t play, we don’t need you.”

If you covered Parcells, played for him, coached with him, or just happened to watch his conferences, you may be familiar with something he said about 146 times a season: “I go by what I see.” He didn’t care about the hype or what people said about players—only what he saw them do.

“What happened in Hastings,” I said to Parcells, “sounds like the origin of ‘I go by what I see.’ ”

“It’s true,” he said. “So, that’s my Hastings story.”

Army, 1967-1969

Linebackers coach; assistant basketball coach to Bob Knight

Parcells (front row, second from right) was the linebackers coach at Army—and an assistant coach for Bob Knight's basketball team. (Courtesy of Army Athletic Communications)

“Before I tell you my Army football story, you want to hear about our basketball games we used to play at noon? Pickup games, lunchtime. There’s me, there’s Knight, there’s Don DeVoe, who went on to coach Tennessee, of course. And now this name will ring a bell too—you know Dave Bliss? Went on to coach a few places, and he’s in the service at the time. We had a guy who’d played at Syracuse, Dick Taylor, and a guy who went on to play for the Chargers for four, five years, Bob Mitinger. Called him Gravy Train, because he was always there for all the free lunches. Then we’ve got Norman Schwarzkopf.”

“Schwarzkopf! Insane,” I said. “What a lineup.”

“It’s true. Schwarzkopf. I think he was a major at the time. He might have been a light colonel. That’s seven. Then we had Arthur Ashe.”

“WHAT?!”

“He was in the Army then, stationed at West Point. One of the top players in the world, and he used to practice with another guy stationed there at the time, Ron Holmberg. I’d see them playing. Arthur could get around the basketball court. Pretty good. So that’s our eight players for pickup basketball.

“I really wasn’t much of a basketball coach there. I just sat on the bench for home games, when I wasn’t recruiting, and in the NIT against South Carolina and Frank McGuire. Mike Krzyzewski was on our team. Sometimes I’d scout. I scouted Tennessee once.

“So now you wanna hear my Army football story? This is about a game. We’re playing Stanford in ’67. Do you know the name Gene Washington? He’s playing quarterback for Stanford. The game is at West Point, Michie Stadium. We kick off to them. They drive it for a field goal. They kick off to us, we’re three-and-out. We punt and they drive all the way for a touchdown. Ten-nothing. I mean, the national anthem ain’t even over. We punt again, but their guy drops it, and kicks it toward his goal line down to around the 30. We recover it and score a touchdown at the start of the second quarter. They drive again, and have 1st-and-goal on our 4-yard line. But we make a goal-line stand. Now we’re getting near halftime, and we kick a field goal to tie the game up, 10-10 at the half.

“So, the second half. We’re playing just a shade better, but we’re down, like 20-17 with five minutes left. We’ve got 4th-and-1 from our own 36. My high school coach is the head coach, Tom Cahill. He calls for a punt. I’m upstairs and I’m shouting, ‘Coach! Coach! We gotta go for it here, we’re not gonna be able to get the ball back.’ These guys have got 30 first downs, nobody can tell me they aren’t gonna make two more.

“Coach gets mad, with everyone saying go for it. He says, ‘Punt it! Punt that son of a bitch!’ We wind up stopping them, now they gotta punt. We run it back to about their 10. We score the first play. Wait a minute. It gets better! Now there’s two minutes to go. We have to get two turnovers to beat ’em—an interception [that Army wasted by then losing a fumble] and a fumble [on Stanford’s final drive]. But we hang on and win a game we had no business winning. None.

It’s not who plays the best. It’s who’s willing to do it the longest ... That’s something that happened quite often in my coaching career.

“I’ll never forget that game if I live to be 100. I ask Cahill why he punted. I’ve got to know. He’s pissed at the coaches. Because he knows we were all against what he did. On Monday, he’s having his press conference. Now I’ve gotta say, this is why I liked this guy. The reporters say, ‘Well, coach, there seemed to be some discussion about punting and going for it. Seemed to be kind of a chaotic situation. Why’d you punt it?’ Coach says, ‘Well, we’ve got a good punter. His name is Nick Kurilko. Our defense had been playing a little bit better in the second half.’ He gives five or six different reasons. The press says, ‘Did you think of those things all at once during the game?’

“He says, ‘No, I thought of them at the office at 6 o’clock after the game.’

“He was being facetious, obviously. But there’s a few things about coach Cahill. He believed in putting the foot back in football. He wasn’t ready to decide the game just then. And a couple of things he used to say stuck with me. One of them was, ‘There’s a lot of ways to win games. It’s not always the best team that wins. It’s the team that plays the best that day.’ You know, at the critical time, you just play a little better.

“I said to my teams many times: ‘It’s not who plays the best. It’s who’s willing to do it the longest.’ That day against Stanford, we weren’t the best team, but we played the best when it counted. We hung in. That’s something that happened quite often in my coaching career.”

* * *

Parcells spent 19 seasons as a college coach and NFL assistant before getting his shot, at 42, to be the Giants' head coach. (Richard Mackson/SI)

Head coach, 1983-90

“I didn’t know what was going on, really, late in the ’82 season. I didn’t know [head coach] Ray Perkins was thinking about going to Alabama. The assistants were kind of in the dark, and there was an announcement about it late in the season, maybe one game to go. Then [general manager ] George Young told me he wanted to talk to me about the job, and so we talked a little bit. Then he said he’d talk to the owners, and half a day later, he said to me, ‘We want to offer you the job.’ I was surprised, a little bit. I was surprised there wasn’t gonna be a big search committee. But happy, of course.”

Dan Henning piped up: “Tell him the story about your mother.”

“Oh, you didn’t know this one? So I get the job. You know, my mother, she’s not ‘sports.’ She’s from Wood-Ridge, from a blue-collar Italian family. She went to work for Lever Brothers when she was 18, coming out of high school. She had to put the money that she made on the kitchen table. So she was not sports-oriented at all. Now, my father had been an athlete—a very good football player, a track man. Pretty famous too. So I said, I gotta call her up, and tell her I got the job with the Giants. So this is the afternoon, late in the week. Right before our last game. So I call and said, ‘Hey Mom, listen, I just wanted to tell you, so you didn’t read it in the paper, I’m gonna be named head coach of the Giants.’ She says, ‘When are you gonna get a real job like your brother the banker?!”

“She did not,” I said.

“Sure she did. She said, ‘Aren’t you tired of those gymnasiums yet?’ Because you have to understand, her idea of a profession was doctor, lawyer, banker. You know what I mean? Her father worked for the telephone company. That family, you had a trade.”

So I call and said, ‘Hey Mom, listen, I just wanted to tell you, so you didn’t read it in the paper, I’m gonna be named head coach of the Giants.’ She says, ‘When are you gonna get a real job like your brother the banker?!’

The Worthy Adversaries

I: Joe Gibbs

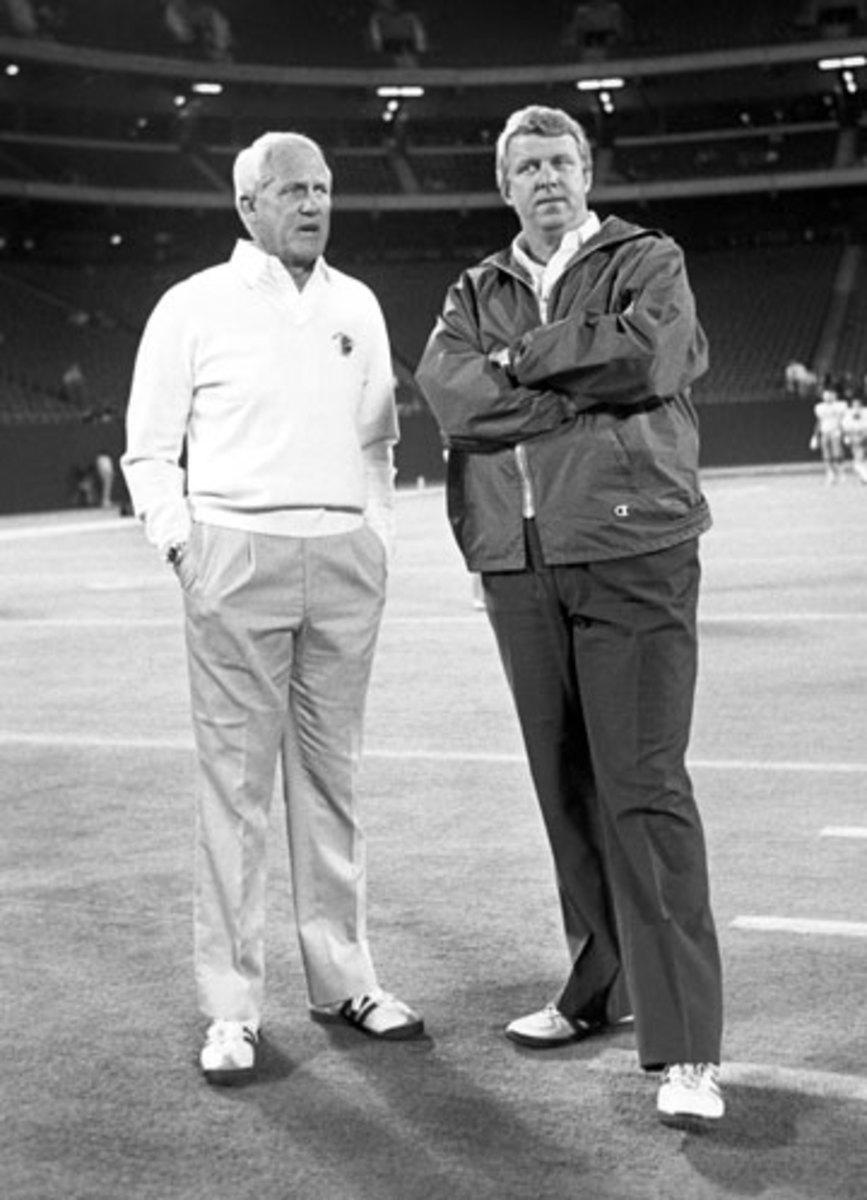

They rarely showed it, but Parcells and Gibbs shared a deep respect for their competitive natures. (Doug Pensinger/Getty Images)

“I think it was ’88 or ’89 … Joe goes on his ‘Blue Day’ crusade. I hear that they have one day a week during the offseason where they’re doing Blue Day. Okay? That’s what they called it—when they’re studying up for us. In ’88, we were going pretty good. So they were after our asses.”

Henning was Washington’s offensive coordinator in 1987 and 1988. He said, “Blue Day. Joe had a game plan for the first three teams of the year. And he would label them because he didn’t want to have a player who got cut be able to say, ‘This is the Giants’ game plan.’ So Joe would color-code the game plans to practice as we would go through the offseason and never say which teams they were for, but the blue one, of course, was for the Giants.”

Parcells: “We get wind of it.”

Henning: “I’ll tell you a little story about that very Blue Day game. Lawrence Taylor was the focus. Well, when we get ready to play that Monday night game that he just described, we had a plan that we would come out in an I-formation, and wherever LT lined up we would shift to him so there would be no open side for Lawrence to rush from. LT gets suspended the Tuesday before that game. We’d been practicing the whole year to shift to 56. And we don’t even think about it. Well, the night before the game we get in with the quarterbacks to meet, and Joe is going over this Blue game plan. I said, ‘Hold on Joe, Taylor’s been suspended, who is Donnie Warren gonna shift to?’ Joe starts thinking—we had to change the whole game plan because Lawrence got suspended.”

Parcells: “So we get wind of it, I’m juicing up my players, like, They’ve been preparing all offseason for us! We go down there, and we are playing good. We got ’em, early. But we don’t have the game won or anything, and we’re down late, in the last minute. It’s 36 seconds to go. I know we hit one pass, and then we hit another pass, and called timeout. We’ve got a 52-yard field goal, and we make it to win the game. That was one of the most satisfying games ever. Blue Day. They put a lot of work into that s--- and we got ’em.”

I always thought Parcells and Gibbs were frosty. Parcells and most coaches were. But it really wasn’t a hate thing—at least it doesn’t seem like it now. Parcells drips with admiration and respect for Gibbs. But then, it was just hard for Parcells to act friendly toward a guy whose ass he lived to kick.

“Dan always tells me we’re the same guy,” Parcells said. “Just different accents, different interests. I get a kick out of this: I’m coaching Dallas, and he gets the Washington job for the second time, and I faxed him one sentence: ‘Does this mean we can’t talk for another five years?’ I know he got a big kick out of this, although he never responded. I heard it from other people.”

II: Bill Walsh

Parcells and Walsh before a Monday night game in October ’87. (Michael Zagaris/Getty Images)

“Bill Walsh, yeah, I’ve got a game. It’s the ’85 playoff game. First game we ever win at home in the playoffs, 17-3. They had beat us in ’84 in San Francisco in the playoffs—best team they ever had. In ’85 they come (to New York). Now, you know he’s got this script right. So, right before kickoff, mysteriously, their phones go out.”

“He knows what he’s doing for his first 15 plays,” I said.

“Right,” Parcells said. “That’s what’s called gamesmanship. Okay, now, we tell the officials we are putting our phones down. We don’t ever put our phones down. We’ve got a contingency for the ‘phones down’ situation. The contingency is that there’s a guy who’s nondescript, who would not be looked upon as someone that would have a phone—but he’s got one. Okay? Because when these things happen, the first thing you think of is gamesmanship. So, I’m really pissed at Walsh. I didn’t know if the phones were really out or not, but back in those days, I’m fighting every windmill. So, it could have been true, but I wasn’t believing that it was true, it was too much of a coincidence. Okay?

“Well, now it’s ’86. We’re playing in the Meadowlands in the playoffs again. Walsh tries to pull the same thing. Calls the ref over. ‘Our phones are out.’ I am pissed. So I have one of our guys go over to talk to Walsh. I say, ‘Tell him, if he doesn’t stop this, I’m gonna expose him after the game.’ Guy goes and tells Walsh. Miraculously, the phones get fixed, suddenly.

“Gamesmanship. Like stealing baseball signs.

“So the game is over. We win by a big score [49-3]. I go to shake his hand, and I’m staring at him. He just smiles and says, ‘You know, you gotta try to get every edge.’ I said, ‘Yeah I guess you’re right.’ You know, you have an understanding of it. Bill is highly regarded in the profession. I think I’d have to agree with that. He was definitely a worthy adversary.”

Best win: NFC Championship Game, 1990

Giants 15, Niners 13

“I mean, you’ve got to remember, we didn’t even dream we could win that game. We’d already lost out there that year 7-3. So there’s another game where they only got seven points. I liked [Niners owner] Eddie DeBartolo. I really liked him. He came into our dressing room after that championship game. That had to be one of the toughest losses they ever had. You know how hard it is for him to come in there and see me and congratulate us? Came in there and shook my hand. There was nobody left in the locker room.

“And that plane trip to Tampa Bay—we flew right to Tampa Bay after the game, because there wasn’t a week between the championship game and the Super Bowl then. That was the greatest trip ever in my life. It was just five hours of euphoria. Drank beer. Relaxed. Went back and hugged the players and congratulated them. They were having a good time too. But you get to Tampa, and it’s over. You just go to work. My secretary met us at the plane, Kim Kolbe. Me and the coaches, we’re down at the office at 5:30, getting ready for the Super Bowl.”

Worst loss: AFC Championship Game, 1998

Broncos 23, Jets 10

“Worst loss ever. Keith Byars fumbled; he didn’t ever fumble. Curtis Martin fumbled. [David] Meggett dropped a kickoff. Just some uncharacteristic play by very trustworthy players. Amazing though—such a windy day, and Vinny Testaverde hit, like, 15 straight passes at one point.”

L.T. was inducted into the Hall of Fame in ’99. (John W. McDonough/SI :: John Biever/SI)

Lawrence Taylor

“Well, you know all the things that I did to him. He can’t beat Irv Pankey of the Rams around the corner, and I put the plane ticket to New Orleans on his locker stool and tell him to fly down there and give Pat Swilling the return ticket because he can beat Pankey. Those kinds of things. But here’s the best thing about Lawrence. And this goes for that team too. I could be not talking to that son of a bitch for three weeks. You know, we would have those times where … contentiousness was not the right word to describe it. It was worse. But no matter how bad it was, no matter how pissed I was at him, no matter how pissed he was at me: Sunday, 1 o’clock, he’s standing right next to me when they’re playing that anthem before the game. Every single time. And you know what that meant? Well, ‘You might be an a--hole, but I’m with you right now.’ That’s really what it meant. I loved him. He was a special kid. The most loyal, to a fault. To a fault.”

Phil Simms

Simms completed 22 of 25 passes for 268 yards and three TDs against the Broncos, earning MVP honors in Sup Bowl XXI. (Andy Hayt/SI)

In 1990, the second Super Bowl season under Parcells, the Giants flew to Indianapolis for a Monday night game. The Colts stunk, and the Giants were winning handily, and suddenly, on the sidelines, Parcells and Simms went after each other, veins bulging.

“Here’s the story,” Parcells said. “It’s simple. We’re putting two halfbacks in the game. Both of them can run around. So we practice it that week. We’ve only got a few plays with them in there, and we’re winning 17-0, so we put them in there. We call the play. Running play. Simms throws it. Throws behind somebody who’s double-teamed. We’ve got to punt. So first thing I say to him, ‘What the f--- did you think I put those guys in there for?’

“He goes, ‘Well, you go out there and throw it then!’

“I said, ‘Sit the f--- down you dummy.’ Now, the players are getting excited. So, O.J. Anderson and Mo Carthon are saying, ‘Bill! Come on Bill! You’re always telling us we’ve got to be a team!’ I say, ‘We’re gonna go back to being a team as soon as I get done yelling at this son of a bitch.’ So that gets rid of those two.

“Now, the game’s over and we win and Simms is walking over. I say, ‘You know, the writers are gonna ask you about this in the dressing room. What are you gonna say?’

“You know what he says? ‘I’m gonna say it was less filling, and you say it tastes great.’ It’s over. You know what I mean? It’s over. No problem. That’s Simms right there.”

* * *

After winning his first Super Bowl in 1986, Parcells desired a second ring even more—which he got four seasons later. (Clockwise from top left: Eric Risberg/AP :: Ed Reinke/AP :: David N. Berkwitz/SI [2])

The end

“Winning the Super Bowl represents a great sense of satisfaction. Team satisfaction, personal satisfaction. You can’t deny that. But you know what? Bobby Knight told me two days after the first Super Bowl we won, ‘You’re gonna want to win the second one more than you wanted to win the first one.’ He was right.”

Now Parcells is talked out. He’s sat on the Saratoga patio on this postcard afternoon for three hours, and he’s getting more clipped with his answers. This game’s over.

“You ought to end the article with that, from Knight. You win one, you want to win the second one worse. Because that’s the trap. You can very seldom satisfy yourself. I was with a guy this morning. His name is Wayne Lukas. You know him? This guy won more horse races, more Breeders Cups—he’s won 14 or 15 major Triple Crown races and Breeders Cups. For the last six or seven years he’s been down. Well, this year, he comes back and he has a horse finish second in the Belmont Stakes and win the Preakness. Okay? So he’s back on top. Now this sumbitch is 77 years old, and he’s up on this horse every morning at 4:30. Every day. He’s out there this morning, this Hall of Fame trainer, at 4:30 riding a horse. He can’t stop. He can’t get enough. It’s like, you can’t win enough to make yourself happy. You win, and it’s just momentary.

“You can’t win enough. That’s the trap.”

It would be sunny and bright to cap the story with a happy ending. Parcells is going into the Hall of Fame this weekend, which makes him happy. But the fact is, he was never all that happy when he coached, even when he won. At least not for long. He never let his players or coaches get comfortable. He fought comfort his whole career. When he got enough money to actually be comfortable, in his several retirements, he fought that too. He kept wanting to go back to the game, as a coach or consultant or something.

“That’s the trap,” he says with a kind of realistic desperation in his voice, as though there is absolutely no other way. And for Bill Parcells, there was no other way.

Forever in the Moment

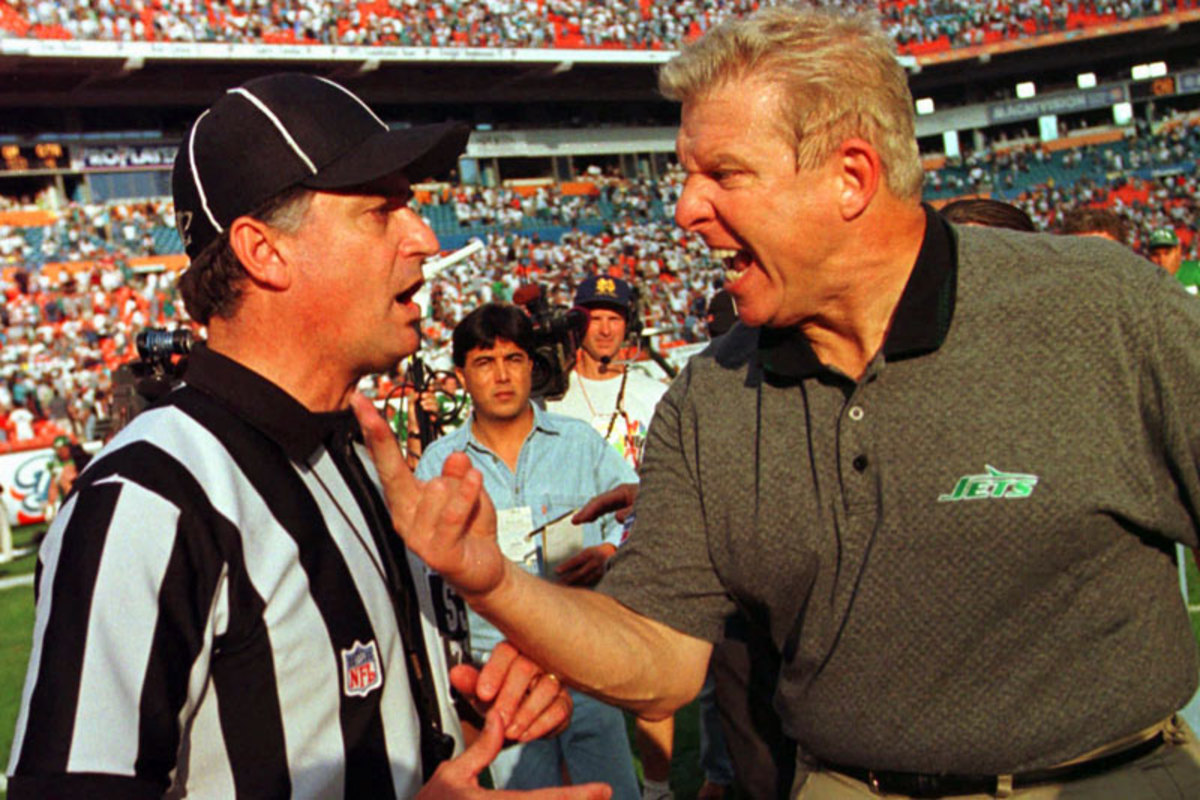

In 22 seasons, Parcells went 172-130-1 with the Giants, Patriots, Jets and Cowboys. (Matt Slocum/AP)

He took all four franchises to the playoffs, winning 11 of 19 career postseason games. He won Super Bowls XXI and XXV with the Giants, and took the Pats to Super Bowl XXXI. (Peter Read Miller/SI)

He had just five seasons with sub-.500 records. (John Iacono/SI)

Although Parcells and Taylor often had a contentious relationship, they had each other's backs in battle. Here they run off the field triumphantly at Super Bowl XXV. (John Biever/SI)

He desperately wanted rings, but Parcells' relentless drive made the thrill of victory ultimately fleeting. (Bill Waugh/AP)

Parcells was twice named NFL coach of the year—with the Giants in 1986 and the Pats in ’94, when he led New England to a 10-6 record following a 5-11 year. (John Iacono/SI)

The was often a madness to his method: Parcells had the league's best two-year turnaround of a 1-15 team, leading New York to a 9-7 mark in ’97 and 12-4 in ’98. (Hans Deryk/AP)

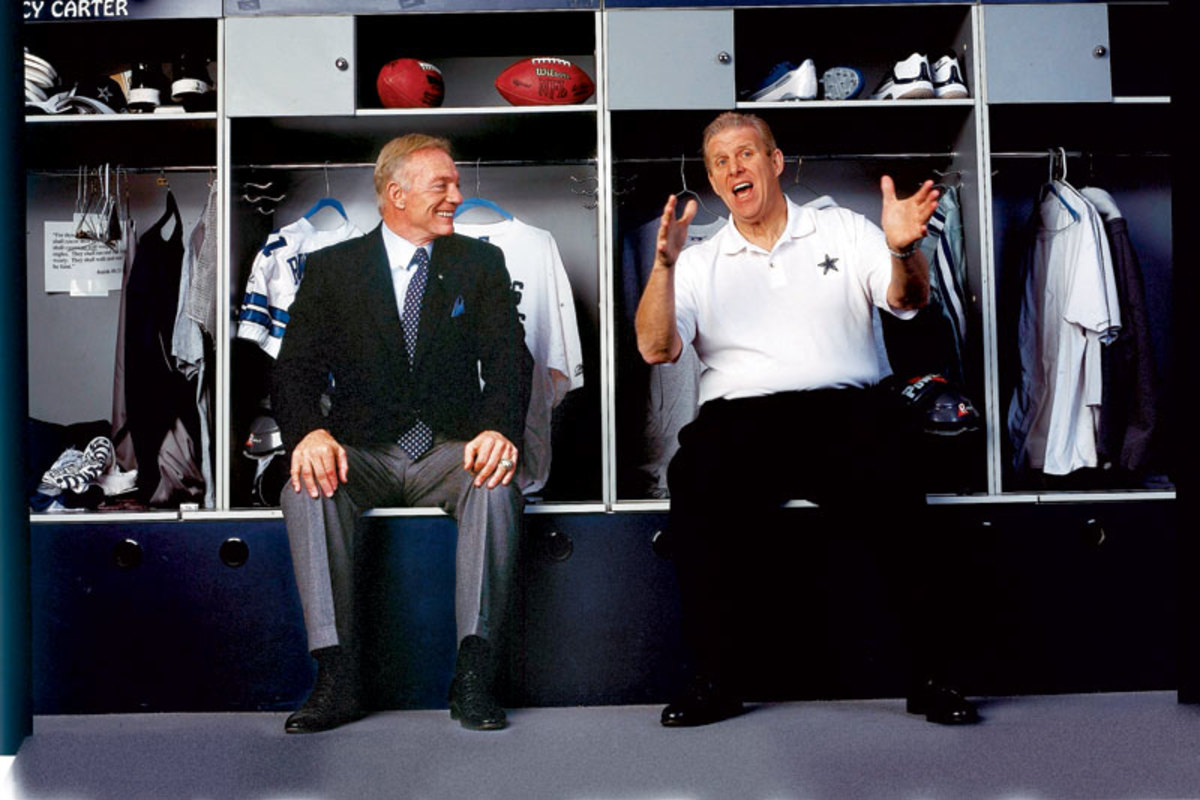

After the Cowboys went 5-11 for three straight seasons, Parcells was hired in 2003 and made Dallas a 10-6 team. (Darren Carroll/SI)

The Big Tuna. (Bob Rosato/SI)