D.J. Hayden’s Heart Is In the Game

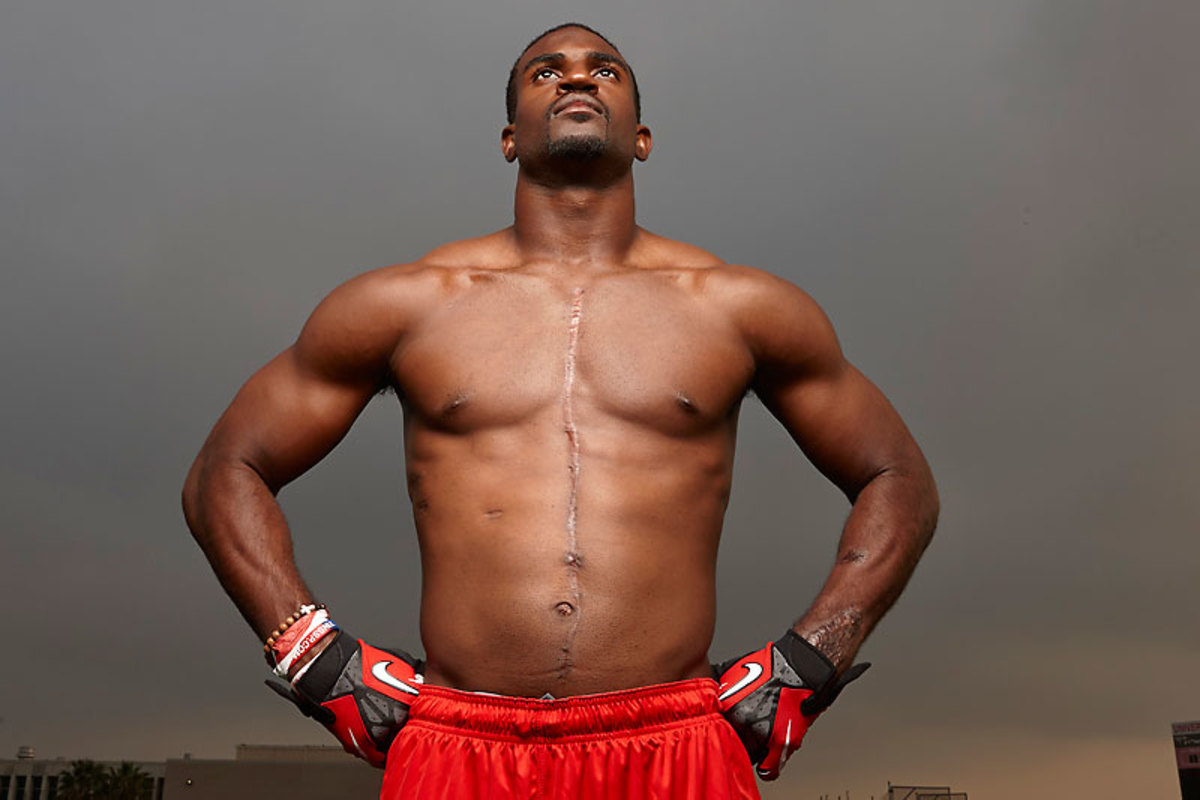

D.J. Hayden, photographed in March in Houston. (Robert Seale/SI)

INDIANAPOLIS—Tori Hayden had a son, and she raised him as a single parent. She dropped out of college to do it. He chose football, and she didn’t worry about the potential for broken bones or a bruised brain; she was just happy he wasn’t selling drugs or buying them. Football helped raise him, drove him to college, and then it nearly killed him. He’s got an 18-inch scar running down the center of his chest to prove it. But he refused to quit on football, and 10 months after his heart nearly gave out on him, Tori’s son is playing against the biggest, fastest men she has ever seen in person.

Sitting in Section 137, Row 4, Seat 8 at Lucas Oil Stadium on Sunday afternoon, D.J. Hayden’s mom squirmed as the rookie cornerback chosen in the first round of April’s NFL draft made his regular-season pro debut. He entered the game on Oakland’s first defensive drive. She could tell it was him by the way he walked across the field, the way he stood, the way he crouched in position.

“Oh Lord,” she whispered, covering her mouth with her hands. “They’re gonna throw at him because he just got out there.”

Maybe you know the story: Hayden was polishing off a stellar senior season at the University of Houston when one day at a November practice a teammate’s knee struck his chest, tearing the inferior vena cava—the major vein that cycles blood from the lower body to the heart. Most commonly the result of high-speed vehicle collisions, the injury proves fatal for 95% of those afflicted, according to the university’s team doctor.

Darrius Heyward-Bey got the best of Hayden on a slant in the first half, but the rookie made the tackle—and mostly held his own for the rest of the day under the watchful eyes of him mom. (AJ Mast/AP)

But Hayden lived—it helps that football teams have medical staff immediately at hand; Houston’s medical trainer acted quickly to get Hayden into an ambulance and to a hospital—and after recovering he was cleared to play football. He was drafted by the Raiders, who many believe gambled with the 12th overall pick. Hayden had an impressive resume on tape, and glowing character endorsements—he was voted a near-unanimous team captain as a senior after only one year in the program, and he finished his degree in sociology while rehabbing the injury in the spring—but several teams took him off their draft boards for medical reasons alone. Plus, even if he was physically OK, could he ever be the player he once was? The Raiders had their concerns too, holding Hayden out of full contact until two weeks ago in the third preseason game, against the Bears. That day, Tori was so nervous for her son’s first play that she reached down and dug her fingernails into the leg of the understanding stranger sitting next to her. On Sunday she was still nervous, but less so. Wearing an autographed, black No. 25 jersey, Tori predicted the play when the Raiders trotted out their nickel package on the first drive.

“That’s what the Bears did,” she said. “Go right at the rookie.”

And Colts quarterback Andrew Luck did just that, hitting Darrius Heyward-Bey on a crossing route just before Hayden got hands on him to drag the receiver down after a 16-yard gain. “I knew it,” she said.

Tori was once what you might call a helicopter mom. Born in Kentucky, she dropped out of Prairie View A&M in Texas upon having D.J. She moved to Houston with him and was working for a an energy company in town when D.J. went to college, and when word got to her from a coach that her son was slipping academically and showing up late to one of his classes as a junior-college transfer, she came to the lecture hall at UH to confront him. Yet when Hayden was faced with a life-altering decision—whether to continue playing football after emergency heart surgery and six days in critical condition—she stepped back and let him decide.

“I wasn’t completely fine with him coming back, but I told myself he’s a grown man and he can make decisions for himself,” she says. “He knows his body, he knows his limitations and he’s always made good decisions, so I just felt like he could make it on his own without me.”

Hayden had more than two dozen snaps on defense and special teams and had his NFL moment against Reggie Wayne. (AJ Mast/AP)

But she kept watching, and worrying. She’s cautious about asking him about his health; after seeing how confident he’s become, she doesn’t want to project her fears and concerns onto him. But they were evident as Tori watched each snap from her stadium seat, eyes fixed upon D.J., hoping only that he doesn’t get hurt.

After Heyward-Bey’s first down, the rest of the game was more encouraging for Tori, her uncle and Hayden’s agent, Graylan Crain, sitting side by side. With eight more defensive opportunities in the first half, Hayden shut down his opposite numbers—T.Y. Hilton and Heyward-Bey—and Luck didn’t look his way. On two punt returns he was the jammer across from the punt team’s gunner, but the 23-year-old forgot he was allowed to jam the hopeful tackler.

“At first I just let him run, and ran with him,” he said later. “I realized that I could put my hands on him. I put my hands on him and I think I did good.”

By halftime Tori was alarmed by the speed and ferocity of play, shrieking as Colts linebacker Erik Walden clawed for a forced fumble. “They’re too rough out there!”

But she grew more confident in D.J.—his play and his personal safety—as the game wore on. By the third quarter she watched the Raiders as a whole, with an eye on her son. “Now I just want him to get an interception,” she said. “That’s a drastic change, isn’t it?”

The Raiders led as late as the fourth quarter behind an inspired performance by the defensive line and quarterback Terrelle Pryor. With less than 10 minutes to play, the Colts faced 3rd-and-2 at their own 42 as Hayden lined up across from six-time Pro Bowl receiver Reggie Wayne. Hayden says he knew what was coming: Luck zipped a slant to Wayne, and Hayden closed fast, making contact with Wayne as the ball arrived and nearly swatting it away. He jumped to his feet in celebration, only to realize a moment later that Wayne had caught the ball for a first down.

That, he says, was his ‘Welcome to the NFL’ moment.

“I thought I broke it up, but he caught it,” he says. “I thought it was good coverage. I’ve got to work on finishing the play.”

The Colts went on to score the game-winning touchdown on the drive, Luck scrambling 19 yards past Hayden (who was in man coverage on Heyward-Bey, with his back turned to the QB—he's No. 25 in the video below) and the rest of the Raiders for a 21-17 lead. Pryor threw an interception in the final seconds at the goal line, ensuring a Colts victory. Hayden went without a breakup or a big hit on a par with his tackle of Matt Forte in his preseason debut—a torquing, slamming takedown that he says was the most contact he’d endured since the injury. This time around he played more than 25 snaps, the majority on defense as an outside corner in nickel. He was targeted three times, giving up up three catches for 37 yards and making the tackle each time.

“I wasn’t really nervous at all,” he said afterward. “I feel normal. I was just happy to be back out there doing my thing.”

After the game Hayden dressed in the black slacks and shirt he bought at Men’s Wearhouse before the preseason and the black and white blazer he picked up at Express, and shared a hug with his mother, who waited on the other side of a hip-high metal barrier separating family and friends from players as they made way to the team bus. She asked him how it felt: “Like a football game,” he replied, bluntly. Head coach Dennis Allen stopped by, hugged Tori, shook hands with her uncle and agent, and offered his congratulations and encouragement to Hayden. Fellow Raiders rookie Sio Moore stopped by too, reminding DJ of his third-down gaffe.

“Next time, see the play before you celebrate,” he said, grinning.

Moore and DJ have become close, rooming together on the road and in training camp and now sharing an apartment. While DJ sends mostly one-word answers to regular texters such as his agents and his mom, he has opened up to Moore recently. The linebacker is convinced DJ has mentally overcome nearly dying less than a year ago. Like a shark-bite victim who returns to surfing, Hayden felt he had no choice but to dive back in.

“People assume he’s nervous,” Moore says, “but he just goes out there with a mentality to play ball. Had he been like that, nervous, that would hold you back. We’ve had conversations; he’s good. He just wants to stop talking about it.”

In the media, sure, Hayden answers obligatory questions about the injury with curt-yet-polite one-liners. In postgame locker rooms he prefers to put on a shirt before facing the media, so as not to draw attention to the scar running down the middle of his chest. But at home with Moore he walks around shirtless, and on fishing trips too; not showing off, but not hiding either.

“He wears it with pride,” Moore says of the scar. “It’s not something he’s ashamed of or doesn’t like. It’s a badge. Whenever he wakes, and especially when we go out on the field, he remembers what it took for him to get here.”

Hayden, fishing in Galveston Bay this summer, didn’t look like a guy overly worried about his past injury. (Courtesy of Graylan Crain)