Oz the Great and Powerful

On Friday, April 19, 1996, the brain trust of the brand new Baltimore Ravens was sitting in the windowless draft room at the team’s training facility housed inside an old state police barracks in Owings Mills, Md. After the exodus from Cleveland that ripped the hearts out of Browns fans, there was plenty of work to do in building the new franchise. The group had been working non-stop, not only on the draft, but on trying to make their new space functional. It still wasn’t close to that. In the hallway outside, VHS tapes numbered 1 to 2000 were lined up on the floor against the wall up one side and then back down the other, because there were no storage units. People would roam the halls, yelling, “Where’s Virginia Tech vs. Virginia?” Television monitors were strewn all over the place. The stationery had a blank white helmet on it. The practice uniforms were black and white, drawing jokes about the Mean Machine from The Longest Yard. College secretaries, not knowing that the Ravens were a real NFL team, sent scouts on campus visits to the soccer offices.

“You talk about a wing and a prayer,” says Phil Savage, the team’s director of college scouting at the time.

But there they were, one day before the first draft in Ravens history, charting the course for a franchise. Present were owner Art Modell, his son David, team president Jim Bailey, chief financial officer Pat Moriarty and vice president of player personnel Ozzie Newsome.

Newsome, 40 at the time, was in charge, but he was greener than the Jolly Green Giant. After starring for four years at Alabama and then for 13 seasons as a tight end for the Browns, he was certainly at home around the game. But this was altogether different. Yes, he had studied tirelessly in the five years since his retirement, working at times as an assistant coach with Cleveland, and then in personnel under coach Bill Belichick with the Browns. But in Cleveland, Belichick, general manager Ernie Accorsi and later personnel chief Michael Lombardi did the heavy lifting. Everyone else was a glorified grunt, grinding tape and writing reports.

When Art Modell moved his franchise to Baltimore, he handed Browns legend Newsome the task of building the roster for the newborn Ravens. (Roberto Borea/AP)

During his playing career, Newsome had become very close to Modell. Maybe the owner didn’t have many options or people he could trust after the controversial move out of Cleveland. Whatever the reason, he chose Newsome to direct the front office. “There’s a difference between managers who make purely intellectual decisions, and managers who manage intuitively from the gut,” said David Modell about his late father. “I think Art obviously had that sense of people, because say what you want about him, he was definitely a people person. He had a feeling about Ozzie.”

Powerful people in the NFL face critical decisions at some point in their careers. The inexperienced Newsome, armed with the fourth and 26th picks in the first round, was staring his seminal moment in the face, just a few months into the job. His choices in this draft could shape a franchise, or spin it further into the vortex of irrelevance.

Art Modell and coach Ted Marchibroda preferred to make a splash in the new market with an explosive running back—Lawrence Phillips from Nebraska. The Ravens desperately needed someone in the backfield. Seemed like a good marriage.

Newsome kept coming back to an offensive tackle from UCLA named Jonathan Ogden, even though the team already had a good offensive line and a solid left tackle in Tony Jones, who would go on to start two Super Bowls.

It was Newsome’s moment. One that his whole life had prepared him for, and set the stage for greatness.

* * *

The story of Ozzie Newsome, better known in the state of Alabama and in the NFL as the Wizard of Oz, is difficult to tell neatly or traditionally. Newsome is a transcendent figure in football lore, who after rising above segregation in the South played for the great Bear Bryant at Alabama, achieved personal success as an NFL player but endured heartbreaking team failures, and then rose to become one of the most powerful and successful figures in personnel.

And you can’t tell Newsome’s story with his help. He declined an interview request for this story, just as he does most all other reporters who want to focus on him. What follows are the stories, anecdotes and quotes culled from interviews with 19 people who have known Newsome well over the course of his life.

All of them are pieces to the puzzle. Put them together and they serve as a portrait of the man who has helped lead the Ravens to two Super Bowl titles, five straight playoff appearances and nine in the past 13 years.

Newsome played mostly end under Bear Bryant at Bama but would move to tight end—he had the build for it—in the pros. (George Long /Sports Illustrated)

Alabama Born and Bred

To know Newsome is to know that he is exceedingly private. Some Ravens employees have worked alongside him for years yet have never been to his house, nor do they know where he lives.

That privacy extends to information about his childhood. Newsome was born in 1956 in Muscle Shoals, Ala., and was raised in nearby Leighton in the northwest part of the state, not far from the Tennessee border. It was a time of segregation, and one of the few Newsome confided in over the years was David Modell, who viewed Newsome as an older brother. Modell would prod Newsome for details about his childhood, and he finally relented and told tales of drinking from Colored-only fountains, and having to go in the back door of the theater and up to the balcony to watch movies.

“It enraged me and enrages me to this day,” Modell says. “Unbelievable that someone treated my big brother that way. I know what kind of man he is. To think he was treated a certain way because of the color of his skin is enraging.”

In what would be a theme throughout his life, Newsome dealt with the era’s institutional bigotry with an even temper. He learned at a very early age to turn the other the other cheek. “He would simply say, ‘Times change,’” Modell recounts. “But this is a part of the story that should not be missed.”

Newsome, who would become the NFL’s first African-American general manager, reportedly broke color barriers in Little League and middle school, venturing into spaces previously reserved only for whites. His father, Ozzie “Fats” Newsome Sr., and mother, Ethel, were strong influences. Ozzie Sr. had a restaurant called “Fats’ Café,” where Ozzie and his four brothers learned hard work—when not picking cotton—and how to deal with people from all walks of life. Ethel was a domestic worker and ran the household. Those who know both Ozzie and his mother said he has her personality and patience.

“She’s responsible for the type of guy Ozzie is,” says Steelers assistant head coach/defensive line John Mitchell. The first African-American player at Alabama, Mitchell recruited Newsome for Bear Bryant and the Crimson Tide. “She was reserved. Taught all those kids to be very amenable, speak only when you’re spoken to. Ozzie was very quiet.”

But as a three-sport star and All-State in football and basketball at Colbert County High, Newsome screamed of something greater. He was recruited by every school in the SEC and seemed headed to Auburn with his high school quarterback. Bryant finally was able to win a commitment from Newsome, but he took no chances when rumors circulated that Newsome was wavering. Bryant dispatched Mitchell on the four-hour drive to Leighton.

“Coach Bryant gave me specific instructions to not let Ozzie out of my sight,” Mitchell says.

So for the rest of the day, Mitchell sat in the back of all of Newsome’s classes, took him home and picked him up after his basketball game to drive him home again. Mitchell was still in the Newsome’s modest home around midnight, when Ethel finally told him, “Coach, it’s time for you to go.”

“Mrs. Newsome, Coach Bryant said not to let Ozzie out of my sight,” Mitchell pleaded.

That night Mitchell slept on the couch in the Newsome house. On Ethel’s later visits to Tuscaloosa, she would rib him about the sofa until one day she said, “Coach, we finally go rid of your bed.” They had sold the sofa.

Alabama and Bryant became ingrained in Newsome. He rarely dropped a pass and earned a nickname from Bryant. “He called him Wiz,” Mitchell said. “He had to be very special for that.”

Newsome, a split end in a wishbone offense, caught 102 passes for 2,070 yards in his four-year career, setting school and conference records. He was twice all-conference, and as a senior was an All-American and a co-captain. Bryant, who’d played with future Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee Don Hutson at Alabama, called Newsome the best end in school history—including Hutson. That would make him an Alabama legend forever. Newsome’s love of Bryant, who sent annual handwritten notes to all his former pupils in the NFL signed, “Keep your class,” has never wavered.

Two years ago, Ravens coach John Harbaugh gave Newsome a notebook full of Bryant’s lecture notes that had been passed to Harbaugh’s father, Jack, a longtime college coach. Like a lot of things, it became hidden in the morass that is Newsome’s office. A few weeks ago Harbaugh played interior decorator, pointing out where bookcases and a new closet could go.

“I don’t know if I can keep coming back in here if we don’t straighten this place up a little bit,” Harbaugh told Ozzie. They turned up the Bryant notebook, and Newsome looked at it adoringly.

“Ozzie just cherished that,” Harbaugh said. “He views everything through that Crimson-colored lens.”

There were loads of individual achievements with the Browns—Newsome held numerous alltime tight end records when he retired—but the team’s failures marked his on-field tenure. (John D. Hanlon/Sports Illustrated)

A Game-Changer in Cleveland

Before the 1978 draft, another coach was sent, like Mitchell, to visit Newsome, with very specific instructions. Rich Kotite was part of Sam Rutigliano’s new coaching staff with the Browns. Rutigliano wanted a weapon who could attack the double zone defenses of the day down the middle. That meant he needed a tight end. Newsome was a receiver most of his career at Alabama, but Rutigliano thought he could make the transition if he possessed one unique physical trait.

“I told [Kotite], ‘I don’t want to know anything else except does he have a big butt?’ ” Rutigliano recalls.

A few days later, Kotite returned from Tuscaloosa. As he walked into Rutigliano’s office, Kotite didn’t have any scouting reports or any materials on Newsome. “He just said, ‘Sam, he’s got a big butt.’ I said OK, and we drafted him 23rd overall, after taking linebacker Clay Matthews 12th,” Rutigliano recalls.

Newsome reported for a mini-camp and met with Rutigliano, who told his new player he could make it as a receiver but could be a great tight end. “Coach, Bear Bryant told me to tell you that he thinks I should play tight end too,” Newsome said. “Well, if coach Bryant feels that way, that’s good enough for both of us, right?” Rutigliano replied.

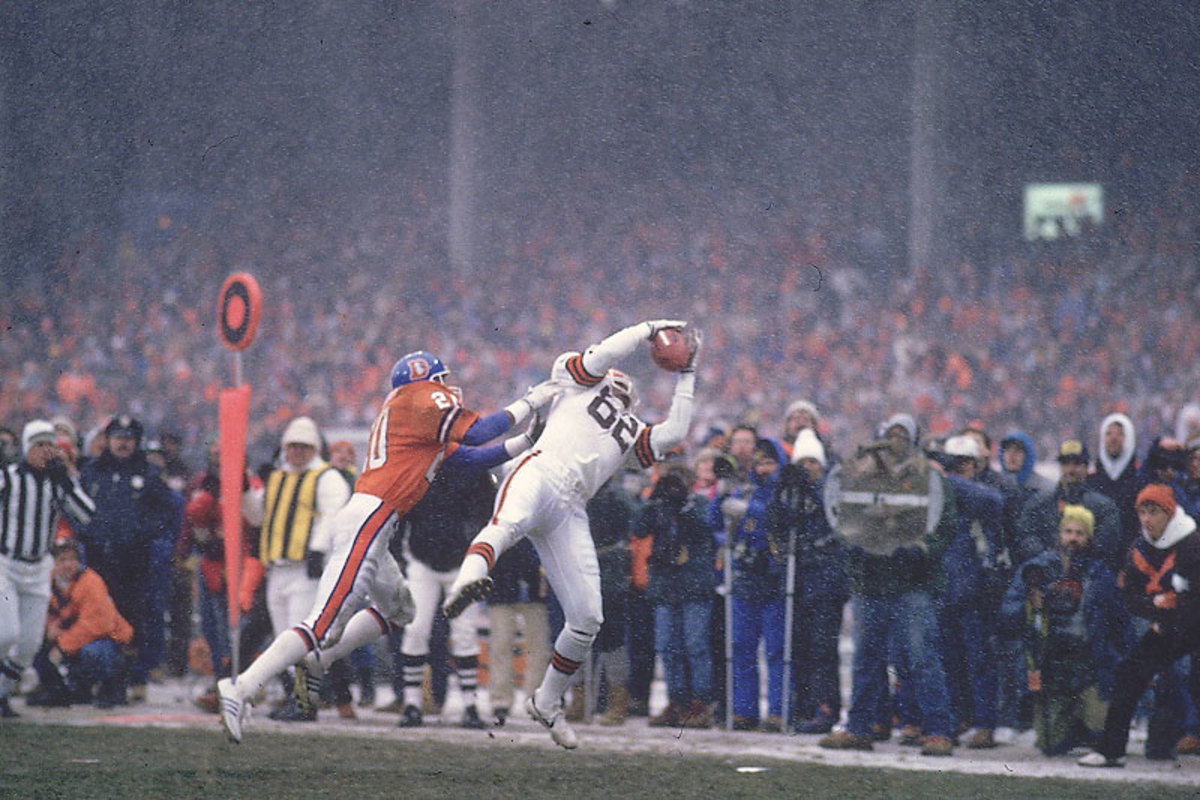

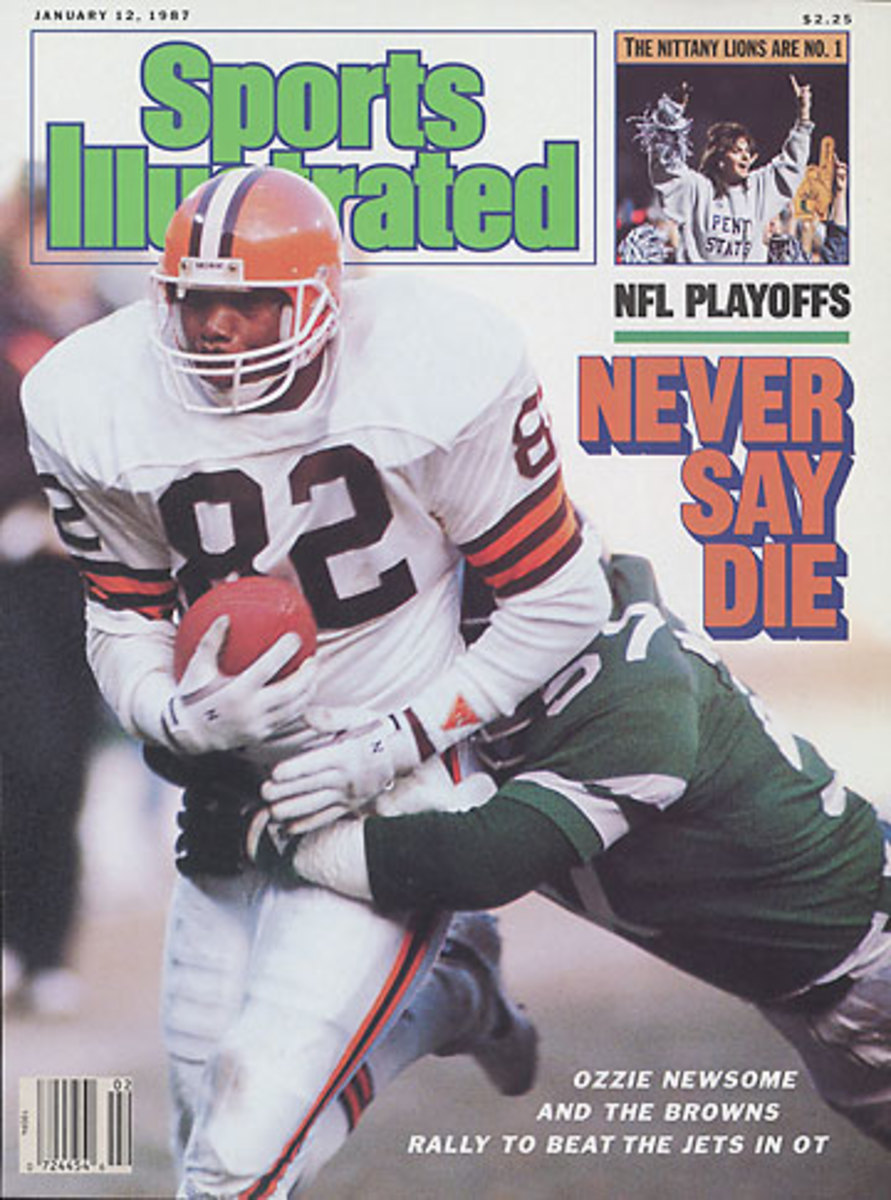

Newsome was hard to cover—except when SI gave him the treatment in January 1987. (Jerry Wachter/Sports Illustrated)

“Yes sir,” Newsome said.

On his first touch in the NFL, the 6-2, 232-pound Newsome scored on a 33-yard reverse. He finished his career with 662 receptions, 7,980 yards and 47 touchdowns, all records for the position at the time. He didn't fumble on his final 557 touches. "It's pretty incredible," Belichick says. "I've used that story many times. We all make mistakes and we need to learn from them." Newsome also caught a pass in 150 straight games, at the time the second-longest streak in league history.

His catching ability, which was likely enhanced by concentration learned playing catcher growing up, was legendary. Rutigliano says the only pass he saw Newsome drop in his seven seasons as Browns coach—and he includes all practices and exhibitions—was in the 47th game in his career, at Minnesota near the end of this third season in 1980.

“I was shocked,” says Calvin Hill, the All Pro running back who spent his final four seasons with Cleveland. “It never happened before. He just shrugged and said, ‘Hey, I dropped the pass.’ ”

Newsome had good enough speed. As for his blocking, former Browns left tackle Doug Dieken said Newsome was an effort guy. In other words, decent. “When you saw his butt, you knew he wasn’t a wide receiver,” Dieken says. “He worked at it. Wasn’t his strong suit.”

During Newsome’s rookie season, Dieken asked him for help against nasty Rams end Fred Dryer and proposed a then-legal high/low block, with Newsome going for Dryer’s knees. After the play, Dryer punched Newsome. “I said, ‘You leave my rookie alone,’ ” Dieken recalls. “Ozzie said, ‘Thanks for sticking up for me.’ He didn’t realize I set him up.”

Off the field and in the locker room, Newsome quickly latched onto the worldly Hill, a Yale grad who as an only child never had a sibling and liked Newsome. Rutigliano liked to joke that Hill read the Wall Street Journal on the team plane while everyone else read the comics. He probably wasn’t exaggerating much. Hill once took the sheltered Newsome to a French restaurant in Cleveland. After the suave waiter went over the menu, he asked Newsome what he would like to order. “I’m not sure what I want to order, but I want to hear you repeat that again,” Newsome said.

Hill, with the help of Rutigliano, would prod Newsome into giving up the traveling basketball games he played in during off-season for extra money and into getting a real job. Newsome worked at East Ohio Gas, recruiting management trainees. It was his first exposure to scouting as a profession. “Calvin Hill was very impactful role model for Ozzie,” Rutigliano says. And Hill was Newsome’s presenter at Ozzie’s Pro Football Hall of Fame induction in 1999.

Starting Over

After never missing a game because of injury in high school, college and the pros—a span of 21 years—Newsome wasn’t sure what to do next when he retired after the 1990 season. Modell told him to try both coaching and scouting, and new Browns coach Bill Belichick didn’t stand in the way.

Most former players, especially one as good as Newsome, either carry an arrogance into their new job or expect things to be made easier for them, or both. But one thing Newsome did in his life, just like his parents, was work. And he did that with the Browns. Newsome drew up the cards that the scout team worked off of, and help run the scout team. Belichick, Accorsi and Lombardi would give him the same jobs as plebes such as Savage.

“Oh yeah, he had all the crummy jobs,” Belichick says. “Just evaluating players from nowhere that weren’t very good, but they had to be evaluated. Hitting the road, scouting guys just like any other scout would. He had never had an attitude like he had all the answers or, ‘I played so I know more.’ He was very receptive to learning as much as he could about coaching, scouting, personnel—all the other things that go into the job. Whatever he was asked to do, he’d do his best for the team.”

In Belichick’s final two seasons in Cleveland, Newsome had risen to director of pro personnel, scouting the league and upcoming opponents. He had yet to do extensive work with the draft. But he did learn one valuable lesson during the 1995 draft, Belichick’s last one as Browns coach. Cleveland was prepared to take Penn State tight end Kyle Brady with the 10th overall pick, but the Jets nabbed him at No. 9. The story, which Belichick and Lombardi have long denied, is that Belichick was so upset he threw a phone against the wall, shattering it. Whether that is true or not, it can’t be disputed that the Browns didn’t have a consensus on a player past Brady, and now he was gone. They finally traded down, bypassing among others Hall of Fame defensive tackle Warren Sapp, to the 30th spot and picking up a first-round pick in ’96. With that 30th pick, the Browns chose Ohio State linebacker Craig Powell, who had two injury-plagued seasons with the team, never starting a game, and was out of the NFL by 1999.

“One of the lessons learned for both of us was if you’re picking 12th, you need 12 players [on your board]. If you’re picking 25th, you need 25 players. Period,” Savage says.

Belichick never got to use that acquired pick. Newsome and Savage did.

Seventeen years after he made him the Ravens’ first draft pick, Newsome helped Jonathan Ogden unveil his bust in Canton this summer. (Tony Dejak/AP)

Conviction

One day before that first draft as director of player personnel of the Ravens, Newsome explained his strategy for the fourth overall pick to the rest of the inner sanctum, especially Modell. The pick would be either receiver Keyshawn Johnson, linebacker Kevin Hardy, Phillips or Ogden.

Phillips had character flags coming out of Nebraska. In the 1995 season he was arrested for assaulting his girlfriend and was suspended for part of the season. Modell and Marchibroda led a group that took Phillips to dinner on a pre-draft visit and came away thinking Phillips could be coached. Modell had started a program called “Inner Circle” to provide psychological and emotional help for players who needed it. It was a source of pride for Modell.

On the field, the team needed a talent like Phillips. The previous season, no Browns running back had averaged more than 46 yards per game. Modell wanted an exciting pick to help him sell tickets in a new city. The Ravens already had a good offensive line. But Newsome and Savage were in lock step.

“If we take Phillips, you will never be able to put your head on a pillow at night and be certain of what he’s up to,” Savage said. “If we take the other guy [Ogden], not only is he an awesome player, but you will never have that concern. Class act all the way.”

Newsome, who to this day prefers to listen and then speak last, had the final word. “Art, we just feel that Jonathan Ogden is the best player, period,” Newsome said. “And that’s who we’re going to take if it comes down to it tomorrow.”

On draft day, Johnson and Hardy went 1-2 to the Jets and Jaguars, respectively, and Cardinals took defensive end Simeon Rice at No. 3. That left both Ogden and Phillips on the board for the Ravens. Modell looked at Newsome. “You have time to reconsider,” the owner said.

“Art, yesterday we made the decision that he’s the best football player, and that’s who we’re going to take,” Newsome said.

“Well, where’s he going to play?” Modell replied.

“Left guard,” was Newsome’s retort, which fell flatter than a cornerback blitzing against Ogden. Newsome relayed word to the staffer in New York to write down the name Jonathan Ogden. At the same time Savage leaned over to Modell and said, “I don’t think we will ever regret what we just did.”

Modell looked at Savage with equal parts “You better be right” and “Who’s this young kid?” The Ravens were off and running.

With the 26th pick, the Ravens were looking for a weakside linebacker to play next to Pepper Johnson, their veteran in the middle. After end/linebacker Marcus Jones went 22nd to the Buccaneers, there was one linebacker remaining on the board whom the Ravens had an interest in: Ray Lewis of Miami.

In the end, with defensive coordinator Marvin Lewis’s input, the Ravens felt Lewis could play weakside for at least a year.

History will show that Newsome’s Ravens were born with two future Hall of Famers drafted to play out of position as rookies. Ogden spent a year at guard before Tony Jones was traded to the Broncos for a second-round pick (which became defensive back Kim Herring). Lewis was so good that the Ravens made room for him at middle linebacker by cutting Johnson before the 1996 season.

Patience

In 1997 the Ravens were in the market for a defensive end, and Cardinals free-agent Michael Bankston was the target. After picking the brain of Moriarty about the salary cap since its advent in ’94, Newsome and his tutor had become effective at what Newsome likes to call “scrimmaging.” Before any negotiation, Newsome, Moriarty and other top brass sit and determine what the market is, and what a player should be paid.

The Ravens reached a stalemate with Bankston and decided to move on. Modell wanted to know what happened. Owners certainly don’t mind the buzz created when news breaks of the team signing a top free agent. “The numbers were too high, the value wasn’t there,” Newsome told Modell.

Two weeks later Seahawks end Michael McCrary came on the market. For the same money, the Ravens ended up signing a better player. McCrary had 51 of his 71 career sacks over the next six seasons in Baltimore and went to two Pro Bowls. Bankston had 12.5 sacks in his final four years.

The kind of patience learned by waiting for the world to change as a child in the segregated South would become a weapon for Newsome.

“He is a very patient, patient guy,” said Ravens senior vice president for public relations Kevin Byrne, who has been with the franchise for 33 years. “He believes oftentimes that things will work themselves out without having to make a dramatic, drastic decision.”

The Road Taken

Newsome’s next bout with draft-day drama would come in 1999, after a third-straight losing season resulted in the firing of Marchibroda and hiring of former Vikings offensive coordinator Brian Billick as head coach. Before the draft, the Ravens traded a third-round pick to the Lions for quarterback Scott Mitchell (and would later also sign Tony Banks), leaving them with selections in the first, second, fourth (two picks) and seventh rounds. All agreed to take cornerback Chris McAlister with the 10th overall pick. In the second round the Falcons called and inquired about trading for the Ravens’ pick, in exchange for a first-round selection in the 2000 draft. Newsome explained the deal to Modell and concluded that it was a good trade for the Ravens.

Billick, who had some new-coach cachet, wanted players he could coach now, and Savage, who wanted to protect the work his scouts did, disagreed with Newsome.

“We need players. We need players now,” Billick said. “We don’t need players next year.”

“I understand that,” Newsome said, “but that’s a lot of currency for a second-round pick.”

“It could be the 32nd pick next year—they beat my old team to go to the Super Bowl,” Billick responded.

Newsome replied, “I don’t think it’s going to be quite that low next year.”

As the pick got closer, there wasn’t much talk in the room. Modell looked at Newsome and asked his opinion. “I like the Atlanta trade,” he said.

Billick became more forceful. “Ozzie, we need players. The reason I’m here is you don’t have enough good players. That’s why Ted got fired and I’m here,” Billick said. “We have a chance to get a good player. You tell me there are good players up there that will help us win.”

“This will be good for us in the long run,” Newsome said quietly, with five names of possible prospects on the board. “I’ll guarantee you this: one of those five guys will be there in the fourth round.”

Billick shook his head and said, “Ozzie, you have to take a player in the second round. Art, he’s got to take a player in the second round.”

At this point, Newsome, seated at the head of his table, put his elbows on the edge, leaned forward and looked to his right at Modell. The owner looked at Newsome, then at Billick. “He makes the choice,” Modell said, pointing at Newsome. “It’s his draft.”

“We’re going to make the trade with Atlanta,” Newsome said quietly.

Billick walked out the room angrily. Savage also gritted his teeth.

That season the Falcons fell from the Super Bowl to 5-11. As a result, that trade brought the Ravens the fifth overall pick.

Sharpe became a key contributor to the Super Bowl team in the first of his two seasons in Baltimore. (John Biever/Sports Illustrated)

Fitting the pieces

The Ravens made several critical personnel decisions in the 2000 offseason that not only showed Newsome’s eye for talent and his ability to identify the inner drive of a champion, but also reflected his personal touch with players. Some personnel directors never venture into the locker room or interact much with players. Better to not get too close, so personal feelings don’t get in the way of business. Newsome, in contrast, views interaction with his players as a pillar of his job, so much so that he never scouts on the road—he’s always in the building and at practice.

Before the draft, the Ravens hosted Tennessee running back Jamal Lewis on a visit. Newsome asked him one simple question: “What sets you apart from all the other running backs?”

“I can be as good as or better than any back in the AFC,” Lewis said.

On draft day Newsome called Lewis when the Ravens were about to select him with that fifth pick from the Falcons, and reminded him of their conversation.

“I just felt like he really took a chance on me,” says Lewis, who was only 20 at the time. “I only played 25 games in college. Hurt most of my sophomore season, left as a junior. When I first came in, my main goals were to please Ozzie and show that he chose a great player as that first pick.”

Two months earlier, free-agent tight end Shannon Sharpe jumped on Modell’s plane and flew to Baltimore with the owner for a visit. Modell left the league’s best tight end with an all-time great at the position. “Don’t mess this up,” Modell told Newsome. “I want him signed.”

Newsome was straightforward with Sharpe, who’d been a four-time All-Pro and a Super Bowl champion with the Broncos. “I just need you to be you. I want you to be you,” Newsome told Sharpe. “Don’t change anything from what you did in Denver. That’s the player we need. We need your leadership in the locker room, we need your ability to make big plays on the football field, and we want our young guys to see what it takes to be a champion. I don’t want you to change anything. I brought you here for who you are. So don’t get here and think you have to be somebody else.”

Sharpe, recalling the conversation, says, “That was all I needed to hear.”

With Lewis supplanting Priest Holmes in the backfield, Sharpe attacking defenses like Newsome used to, and a mostly home-grown defense shutting down opponents, the Ravens were finally flying under Newsome.

The Show At Last

Newsome enjoyed immense personal success as a player, but team success was fleeting and heartbreaking. While at Alabama, the Crimson Tide when 42-6 in his four years and won three Southeastern Conference championship, but never a national championship. The Browns were … well, they were the Brownies, always finding new ways to come up short, from Red Right 88 to The Drive and The Fumble. The Ravens, too, were 24-39 in Newsome’s first four seasons in Baltimore, before breaking through with a 12-4 mark in 2000 and beating the Broncos and Titans to reach the conference title game. The’ defense was dominant, as Baltimore beat Oakland 16-3. Newsome was finally going to the Super Bowl.

The moment was not lost on Eric DeCosta, who had gone from working at a card table outside Newsome’s office that first year in Baltimore, to Midwest area scout. DeCosta, now the Ravens’ assistant GM, is short on height but long on feistiness, like a lot of kids from his working-class hometown of Taunton, Mass. And like virtually everyone in the Ravens organization, he has an undying loyalty to Newsome—so much so that in recent years he has turned down several chances to run his own team.

As the clock wound down on the Ravens’ first-ever conference championship, DeCosta and Newsome headed for the elevators to get to the field and celebrate an accomplishment years in the making. “All Ozzie wanted to do was get down to that field,” DeCosta said.

In the Oakland Coliseum, which was old then and is ancient now, a mass of people waiting was waiting to get to the locker rooms. As is customary, an elevator was being held for the coaches. Most of the coaches had already descended, but there were two Raiders assistants in an otherwise empty elevator. Newsome started to get on the elevator with the coaches when one of them looked up and said, “Hey, coaches only.” The security personnel also told Newsome he couldn’t get on. It the backdoor of the theater all over again.

With the moment Newsome had been waiting his whole football life for slipping away, DeCosta flew into a rage. “I was furious,” DeCosta said. “I couldn’t believe it. For them to do that to him at that time, it was almost humiliating.”

Then DeCosta felt Newsome’s enormous hand landing softly on his shoulder. Newsome looked at DeCosta and said, “Eric, Eric, … it’s OK. It’s OK, Eric. We’re going to show! We’re going to the show!” So the two waited, and didn’t reach the field until most of the players were in the locker room.

“But he didn’t care,” DeCosta says, “and that’s Ozzie. He really has an incredible ability to stay calm and even-keeled in every circumstance. I really admire that about him, because I don’t have that quality. It’s a gift he has to keep things in perspective. He just doesn’t get flustered.”

Newsome’s second draft pick, Ray Lewis, will be joining Ozzie and Ogden in Canton when he’s eligible in 2018. (Roberto Borea/AP)

Champions

As the confetti rained down at Raymond James Stadium after the Ravens became NFL champions for the first time with 34-7 victory over the Giants in Super Bowl XXXV, Newsome celebrated as much as he is capable. “Thank you for giving me what I was not able to get as a player,” he told Sharpe during a hug.

“Thank you for believing in me and believing that I could still play this game,” the tight end said in return.

At the hotel after the Super Bowl, Jamal Lewis and Newsome saw each other and had a long embrace. One a champion as a rookie, the other’s lifelong quest fulfilled. “He came up to me and grabbed me and he said, ‘You’re my boy. A lot of people thought I was crazy, but you showed them,’” Lewis said. “From that point, we just had this bond.”

The pair remained close.When Lewis went to federal prison in 2005 on drug charges (stemming from an incident in 2000, just after he was drafted), Newsome walked the visiting yard with him, and Lewis was welcomed back to the team for the ’05 season after serving his sentence. As Lewis battles post-career concussion issues, Newsome has offered whatever help he can. “I feel like I ended up with the right organization,” Lewis said. “I was 20 years old. I’m still the youngest player to play in a Super Bowl. I was young. If I hadn’t have gone to that situation, it might have been a totally different story. I joined and was surrounded by a great organization. Ozzie Newsome was the nucleus for that.”

Pride

At the combine in February 2008, Giants general manager Jerry Reese, fresh off a Super Bowl title in his first season as GM, was on the congratulation trail that every winner gets to enjoy. Everywhere you go, somebody’s stopping you to pat you on the back—and maybe catch your eye for a job down the line now that you’ve got the big JS—job security, that NFL rarity.

The lasting interaction, however, came when Newsome spotted Reese among a group in a crowded hallway. When the crowd parted, Reese saw Newsome and the elder executive flashed his big smile—with a message on the side.

“He was just smiling like, ‘I’m proud of you, but it’s not that easy,’” Reese said, laughing as he recounted the interaction. “He’s always been a big supporter of mine.”

In 2002, Newsome was named general manager of the Ravens, becoming the league’s first African-American GM. All those who followed—former Newsome lieutenant James Harris (Jaguars), Rod Graves (Cardinals), Reese, Rick Smith (Texans), Martin Mayhew (Lions), Reggie McKenzie (Raiders) and Doug Whaley (Bills)—have enjoyed Newsome’s guidance and respect him entirely.

“They will tell you that Ozzie has been a guy who will take a call and just talk,” says John Wooten, who worked under Newsome in Baltimore and is now the chairman of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, which promotes diversity in NFL front offices. “That’s what he just does, that’s the way he is. He’s not one of these guys that if you’re not in his circle, you’re not going to get anything from him. They have received great advice. He’s been a great mentor to those guys.”

The truth is, Newsome will give advice to whomever asks his council, no matter their skin color. “Really, Ozzie is an ambassador for the NFL, period,” says Reese, who presented Newsome with an award at the Fritz Pollard banquet in Indianapolis this year.

“I said, ‘I think about three Cs when I think about Ozzie: classy, consistency and championships,’” Reese says. “That’s what I think about. We’re all chasing Ozzie Newsome, man. He don’t talk about it, but go in his office, he’s got skins on the wall. He doesn’t have to talk about it. His resume says it all for him.”

His resume, and the people who know him.

In 2008 Newsome went off the board for a new coach, the relatively inexperienced John Harbaugh. Baltimore has been to the postseason each year since. (Patrick McDermott/Getty Images)

A New Generation

In 2008, Billick was fired after a 5-11 season. To replace him, Newsome and owner Steve Bisciotti, who went from minority to majority owner in ’04, went with an outside-the-box choice in former Eagles special teams coordinator John Harbaugh. During the interview process, Newsome’s reaction to one of Harbaugh’s answers left the candidate feeling uneasy. “He just kind of looked at me, cocked his head and said, ‘Oh … ok,” Harbaugh recalls. “What does that even mean? I figured, ‘Oh, I’m done.’ He didn’t give me more of a read than that. He left it at that.”

Harbaugh’s unease was misplaced. He got the job, is 54-26 in five seasons, making the playoffs each year, and is coaching the defending Super Bowl champions this season. Harbaugh says it helps that Newsome put the general manager’s office across from the coach’s office. There’s no ignoring each other down parallel paths. They’re in it together, for better or worse.

“He has an amazing ability to cut to the heart of the matter,” Harbaugh says. “There’s a lot of complicated stuff that comes between those two offices every single day. A lot of views and varying agendas, things like that. He’ll say, ‘Hey, this is the issue. This is how we should be looking at this.’ To me, it’s really special.”

It has helped Harbaugh that the best quarterback in franchise history, Joe Flacco, arrived the same time he did. That was a Newsome production, even though he never saw Flacco play a game in person.

Before the season, Newsome discusses the team’s needs with his assistant GM, DeCosta, and DeCosta and the rest of what he calls the 20/20 club—eight homegrown personnel men who started as interns in their 20s, making $20,000 a year—go to work. Newsome is hands off with his scouts: Savage says that in the nine years before he left for the Browns’ GM job in ’05, Newsome never once asked where he was going, scouting or doing. “When you have that kind of trust from your boss, that just gives you the latitude to want to do a great job,” Savage says.

Ravens scouts watched Flacco at Delaware long after other teams had left games. They watched him throw in poor weather on the final day of padded practice at the Senior Bowl. They worked him out privately on an uncut field and used Flacco’s own footballs. Newsome wasn’t there. He was, as he always is, watching the tape. And Flacco was their guy.

On draft day in ’08, the Ravens traded out of the eighth spot—not because they wanted Matt Ryan and he was gone to Atlanta, but because they wanted Flacco at their price. After a trade down and a trade up, the Ravens picked Flacco 18th and netted a third- and fourth-round pick for moving down 10 spots.

“One of his best moves was getting Flacco and how he did it,” DeCosta says of Newsome. “We had conviction on Flacco across the board. Ozzie was able to navigate those waters even though it was controversial thing [in the media].”

‘You’re 5-11’

Almost every organization, either before training camp or during it, has an outing for the personnel department. After being on the road for college practices, all of the scouts and staffers get together to compare notes before the college season starts, scattering them all again until the following April. The Ravens’ affair is a happy outing, as old friendships are strengthened and new bonds are formed.

The 2008 dinner at swanky Woodholme Country Club in Pikesville, Md. Was just like the others, right up until Newsome stood up. Not before the meal or after it—during it, as his charges were mid-bite of their tender filets.

“Guys,” Newsome said, as the room dropped dead quiet, like someone had just scratched a needle on a record. “My friend Brian Billick has taken the blame for last season. One of the great coaches, someone I really respect. He’s taken a lot of blame for this team. But I have to tell you guys, the blame is on me. The blame is on me, and some of the blame is on you. We’ve gotten slow and we’ve gotten small. I can’t believe this has happened to us. We’re a small and slow football team. We went 5-11. 5-11. You’re 5-11.”

Play time was over.

“He’s somewhat of a father figure because you never want to disappoint him,” says senior personnel assistant George Kokinis. “We’re not motivated by fear, because we’re confident in our abilities. We’re always motivated because we don’t want to disappoint him. We don’t want to disappoint John or the owner, but really it’s Ozzie. We don’t want to disappoint him. I think that motivates us more than anything.”

Rest assured, the 20/20 club didn’t need to hear from Newsome again. Not that he would repeat himself. Words uttered by those who rarely speak up are delivered with a thousand decibels.

“That really affected me, and that really affected a lot of other people,” DeCosta says. “We’ve been to the playoffs every single year since that speech. I will never forget that speech and the impact that it had on us as scouts. Ozzie took the heat and blame, but he also put a little bit of blame on us and we needed it.”

Newsome cultivates a personal touch with his players and is a common sight at Ravens practices. (Patrick Semansky/AP)

Three years later the Ravens were in the AFC Championship Game. The next year they avenged that loss to the Patriots, then beat the 49ers in Super Bowl XLVII. But Newsome showed this off-season that he wouldn’t rest on his laurels or sacrifice his personnel principles, allowing five-time All-Pro safety Ed Reed to leave as a free agent and trading receiver Anquan Boldin when he thought the price to keep him was too high. The latter move brought criticism that heightened when tight end Dennis Pitta was lost for the season in August and even more so in the opening week of 2013, when the Ravens fell 49-27 at Denver while Boldin starred in San Francisco’s 34-28 win over the Packers. If history is a guide, Newsome will remain unfazed. He’s been here before.

* * *

There is so much more that could be said about Newsome, the man who doesn’t want to talk about himself. He is “is a man of singleness and purpose,” as his good friend Marvin Lewis, the Bengals’ coach, says. “He’s a metronome,” says David Modell. “You can set your watch by him.” Newsome enters the facility at 7 a.m. and checks email. By 8:30 he’s on the treadmill. At noon he’s on the treadmill again, and then has a salad. He finishes the day on the treadmill around 6 p.m.

“I don’t know he’s as big as he is still,” Harbaugh says. “It’s not like he’s heavy or anything. But my gosh, how many calories does he burn on there? And then I see him eating salads? He says that’s where he does his best thinking.”

Newsome and his minions used to jog together at midday before his hip surgery. Marvin Lewis, who was the Ravens’ defensive coordinator from ’96 to ’01, never missed an opportunity to get on the interns about it: “I was teasing a new intern Joe [Hortiz, now director of college scouting]: ‘Joe, until you start jogging with Ozzie, you’re stuck, man, You’re not going anywhere.’ My nickname for DeCosta is Running Man. Always running with Ozzie.”

The NFL’s first African-American GM met the U.S.’s first African-American president at the White House in June. (Charles Dharapak/AP

There’s also the Friday haircut at 2 p.m. every week, and how Newsome is always the person who delivers each fine levied by the team and the league—to maintain his position as bridge from the organization to the players.

Newsome’s loves (besides his wife, Gloria, and son Michael) are Alabama football, Ravens football and golf. No one is sure what the order is. But Newsome will not pick up a golf club until after the draft. Once he does, he’ll play just about every day, even in the oppressive summer heat of a Gulf Coast afternoon near his offseason home in Gulf Shores, Ala. “Ozzie has spent more money on lessons, equipment, greens fees than anybody that I know outside of PGA Tour pros,” Savage says.

Newsome will play with the local power brokers, but also with dozens of junior golfers in the area. He’s done that for years and still keeps in touch with many through text messages. Newsome gives them tickets to games, and even invited some to the Super Bowl in New Orleans.

Newsome is also, quietly, spiritual—he has a private bible session at least once a week and takes his gold cross out from under his shirt for every television interview he does.

The momentousness of the champion Ravens’ visit to the White House, where the first African-American NFL general manager shook hands with the first African-American president, was not lost on Newsome. “I’m so happy my mother is alive so that she could see that,” he told Modell.

The man who is defined in part by his ability to control his emotions lost that control at the cemetery when Art Modell was laid to rest. Newsome’s big sunglasses couldn’t hide the tears streaming down his face. He was so overcome that he had to leave the service. “I have to go,” Newsome told David Modell.

It’s been 17 years since Art Modell took a big risk by putting an inexperienced Newsome in charge of a barely functioning franchise after the emotional move out of Cleveland. Newsome led that franchise out of its morass to its current status as one of the most respected organizations in the NFL.

There’s a saying around the Ravens’ facility: “Ozzie transcends all.” Not only because he’s still there at 57, but for keeping his decision-making process—meaning that of the Ravens—wholly internal. Considering the success he's he's had, and the distance he's traveled, from small-town Alabama to the pinnacle of pro football, maybe the Wizard of Oz does transcend all.

Newsome hoisted the Lombardi Trophy—the second in his tenure with the Ravens—in the Superdome in February. (Win McNamee/Getty Images)