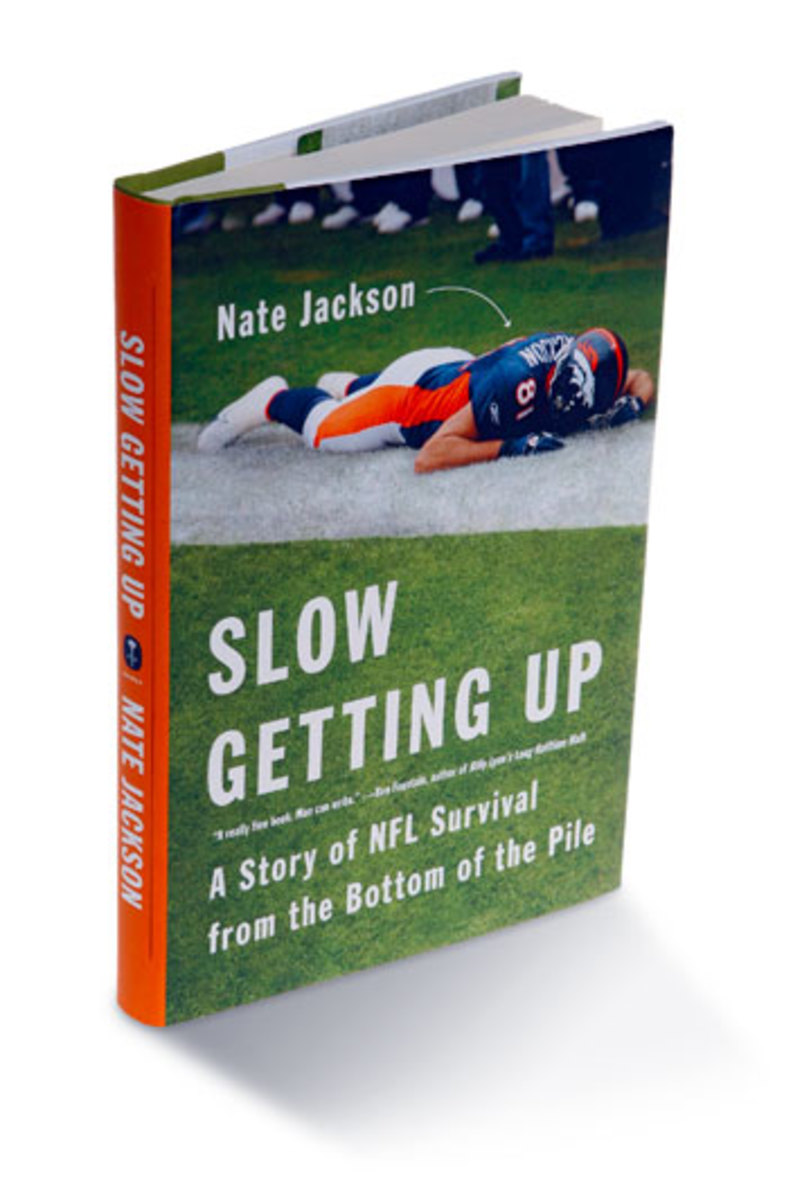

Slow Getting Up

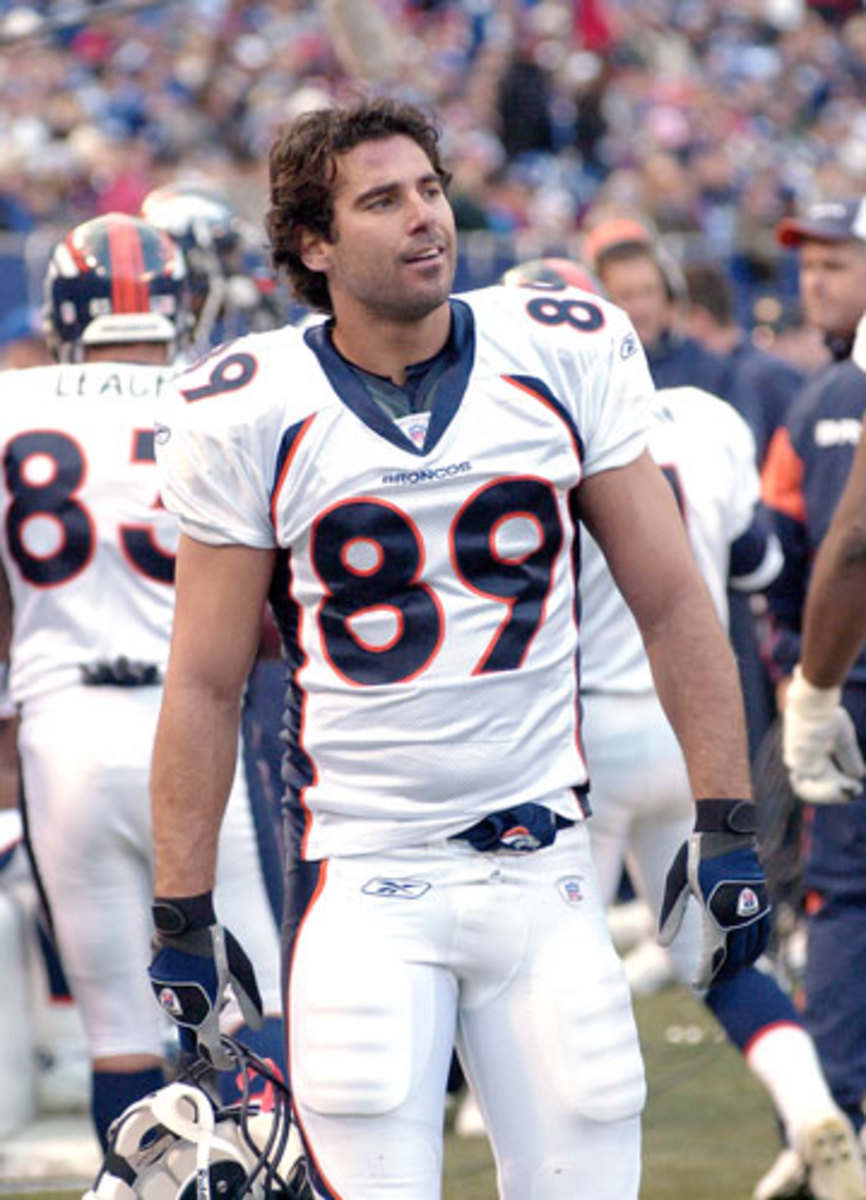

Jackson played six seasons in Denver, appearing in 41 games and making four starts while fighting a constant battle against injuries. It took him five seasons to score his first touchdown, a one-yard pass from Jay Cutler against the Jaguars on Sept. 23, 2007.

By Nate Jackson

Excerpted from the book, SLOW GETTING UP: A Story of NFL Survival From the Bottom of the Pile. Copyright © 2013 by Nate Jackson. Click image for purchasing details.

Every morning when I pull myself out of bed, North Dallas Forty–style, I play out the conversation in my head, what exactly I will say when I go up to Coach Mike Shanahan’s office and tell him I’m quitting, that I can’t take it anymore. But by the time I pull into the parking lot, I have once again convinced myself that I am a warrior, and this is my war.

Training camp is an attack on the mind: an attack on one’s sanity. Enduring it for six years has desensitized me to pain and anguish. Pain isn’t rigid. It’s a choice, a weakness of the mind, a glitch in the system that can be overridden by stones and moxie. I find my switch and flip it. People often asked me how bad it hurt to get hit by those huge dudes. The truth is that it doesn’t hurt at all. The switch is on. I can’t feel a thing. My body is a machine and my emotions are dead.

But the years of abuse are taking their toll. Misaligned joints, stretched ligaments, bruised bones, overworked muscles, and a jangled brain keep pace with an ambitious football mind. One play at a time: one day at a time. My football mind is stronger than my human body.

After morning practice we have a few hours to ourselves. I don’t like to fall asleep between practices. Instead I sit in the locker room and shoot the s--- with Domonique Foxworth and Hamza Abdullah and Brandon Marshall. I’m learning to play acoustic guitar. I sit on the floor and strum the only three chords I know. If someone walks through the locker room we make up a song about him. It’s meant to humiliate and cut deeply, in the hopes of unearthing a crippling insecurity. The more distraught our victim, the more aggressively we laugh at him. The longer he stays, the worse it gets, until he finally realizes he is dealing with madmen who have lost the ability to empathize, and he scurries off. I’m not concerned about another man’s feelings. I don’t even have time for my own. This follows me off the field and out into the world, where people’s concerns seem weak and pointless. Pain is a choice.

I don’t realize it at the time, but the ability to relax and be an a------ between practices is a product of becoming a seasoned pro. My early years in the league were fraught with nervous tension. I was in no mood to joke around. How could I? I was on my deathbed. But as the years have gone by, conquering the daily struggle has become ingrained in my psyche.

Breaking up the monotony of camp is the arrival of the Cowboys for three days of practice leading up to our preseason contest against them. Practicing against another team is difficult. There is an etiquette and tempo that exists at practice that varies slightly from team to team. For us it goes like this: unless it is a live goal-line drill, which only happens maybe once a week in camp, no one blocks below the legs or tackles the legs or touches anyone’s legs in any way. Everyone stays off of each other’s legs because that’s how people blow out ACLs and break ankles. You also don’t take anyone to the ground. You simply “thud up” with a nice pop. You also don’t block a guy in the back or pull on someone’s jersey from behind or take a kill shot on a player or dive on a pile or touch the quarterback at all. You protect each other if possible because the 16-game regular season is brutal enough as it is. And after all, we’re all on the same team.

The Cowboys’ defensive line is enormous and freaky strong. By now I know what I have to do to block a beast like that: crack him in his jaw with the crown of my helmet, then grab him tight and hold on.

But when another team comes in to practice, the lines get blurred. The previous year we had gone to hot, muggy Dallas. We were tired and nursing injuries and didn’t perform well. They were hooting and hollering. They wanted us to know who they thought they were.

After the few days of practices we played the game and got our ass kicked. And they broke a few unspoken rules in the process. Preseason is a time to run your basic s---. No one game-plans heavily for their opponent. But the Cowboys had blitzes and trick plays and all kinds of nonsense. Then they ran up the score when they had us whupped, airing it out with only a few minutes left in the game and a hefty lead.

A wide receiver in college, Jackson became an undersized NFL tight end (6-3, 223 pounds) who finished with 27 career receptions for 240 yards and two touchdowns.

In the team meeting the night before they arrive in Denver, Coach Shanahan reminds us of what happened the previous year. We remember. When practice begins the tension is thick. Wade Phillips, the Cowboys’ coach, has surely just given them the same speech. There is s--- talking, big hitting, and a lot of unnecessary celebrating. HBO’s Hard Knocks is following the Cowboys for their annual training camp series, which does little to limit the theatrics.

The Cowboys’ defensive line is enormous and freaky strong. By now I know what I have to do to block a beast like that: crack him in his jaw with the crown of my helmet, then grab him tight and hold on. And still I’m at a disadvantage. Every run play is internal chaos and insecurity pushed through a makeshift “get-it-done” filter. Visualize the task and f------ do it. On one particular play I’m playing fullback, as tight ends are often asked to do. Years ago Mike Leach had adopted the “the more you can do, the better off you’ll be” credo, and it worked. I’ve followed his lead and it has kept me around, too. But among the do-everything guys, we have another credo: “the more you can do, the more they make you do.” In some cases—such as this one—it works against your better interests. I hate getting put in at fullback. Whenever I do, I look at Pat McPherson like, Really? He looks at me like: Yeah, really, m-----f-----! I came into the league thinking I was going to be a Pro Bowl wide receiver. Now here I am in a three-point stance lead blocking through the two-hole, about to get my d--- ripped off.

A few days later Coach Shanahan throws a party at his home to usher in the regular season. Everyone is in good spirits. It represents an important landmark. This is our team: We go together henceforth. This party is our chance to let our guard down and appreciate the moment. Our girlfriends and wives are with us, buffering out the macho posturing. We can relax and mingle with our coaches in a less stressful setting. As the party winds down, I find myself talking with Coach Shanahan near the front door. He tells me that he is really excited about this team. He loves all of the guys. He says I’m doing a good job out there: that he’s proud of me.

—Nate, as long as I’m here, and you keep doing what you’re doing, you’ll be here, too.

Some words are music to the soul. These are a masterpiece; the iron words I’ve been hoping to hear, or to believe, for my entire career. My hard work is recognized. My skill is respected: by the man who controls my fate.

* * *

Slow Getting Up

Jackson getting dragged to the turf by Raiders safety Michael Huff in the 2008 season opener. (Paul Sakuma/AP)

For his first five years in the NFL, Jackson kept having to prove himself by playing the entire preseason. This catch went for a first down in an exhibition game against the Texans in August 2006. (Doug Pensinger/Getty Images)

Tumbling down with Giants defensive back Will Allen in October 2005. (Nick Laham/Getty Images)

In just his second season, Jackson caught a career-high four passes against the Bengals on Oct. 25, 2004. (Ronald Martinez/Getty Images)

During Friday practice in week four of the 2008 season, I run a hook route and feel something yank in my right oblique area. It’s toward the end of a light practice. It is diagnosed as a “right costochondral irritation at roughly the 10th rib.” Make sense? The next morning we leave for Kansas City. I’m in a lot of pain, possibly the most painful injury I’ve ever played with. Another 60 milligrams of Toradol into my ass the night before the game but it doesn’t help. The muscles in the torso are constantly at work while playing football. Twisting, cutting, exploding, sprinting: all of it activates the obliques. Warmups are so painful that I’m considering the unthinkable: telling coach I can’t play. The Toradol, the adrenaline, and my access to the pain switch: none of them can override this invisible injury. But my pride won’t let me pull the plug. I suit up and tell myself, once again, that I am a warrior, and this is my war. I stare at myself in the mirror and fight back the fear. It is dangerous to be on an NFL field if you’re not healthy. Trained killers are coming for you. As I run on the field before each play, I ask myself: how are you going to get through this? And after each play, I ask myself: how are you going to get through the next one? Eventually the game is over.

More Toradol for the next week’s game, all subsequent games, and all previous games. Every game a needle.

During a Thursday night game in Cleveland a month later, I’m in the slot on the left side of the ball. The fourth quarter is winding down. Jay Cutler snaps the ball and I take off up the seam, bending in toward the middle of the field. I see Jay cock back and throw the ball in my direction. Now it is mine. I must catch it. Catch the brown rainbow. Millions of people are watching, but they don’t exist. I’m alone again inside the timeless moment of football chaos. I give one last grunting burst and leave my feet, shooting out over troubled waters. The ball sinks into my fingertips. I curl my fingers in toward my palms and—CRACK! An M-80 explodes in my helmet. The hit knocks me out for a moment. I get off the field and we win the game.

It is dangerous to be on an NFL field if you’re not healthy. Trained killers are coming for you. As I run on the field before each play, I ask myself: how are you going to get through this? And after each play, I ask myself: how are you going to get through the next one?

I’m dizzy and depressed and my neck is locked for the next week. But I don’t receive any treatment for it. By then I know the drill. Come in to work and get strapped to machines all day so we can log it in the book. I weigh the options in my head: peace of mind or peace of nothing. I choose peace of mind and stay at home where I can rest and medicate myself with drugs of my choosing, drugs that don’t come out of a needle and won’t eat away my stomach lining.

Another routine 60 milligrams of Toradol for the following game in Atlanta.

As the season wears on, my weight drops further and further below acceptable levels for my job description. It’s hard for me to keep on the tight end pounds, because practices are so strenuous, my metabolism is so fast, and I’m never hungry. The weight loss compromises my ability to block defensive linemen. I’m getting thrown around, so every once in a while I take a scoop of creatine to help build muscle and put on weight. But the creatine dries me out. I need to drink a lot of water; otherwise I’ll cramp and be more susceptible to muscle pulls. But I prefer that to getting my ass kicked every day.

Jackson celebrates his second career touchdown, a one-yard pass from Jay Cutler in the first quarter of the Broncos' 34-32 win over the Saints on Sept. 21, 2008. Just days later he would suffer an oblique injury in practice that was the most painful of his career.

The next week, during practice, I accelerate to track down one of Jay’s balls and my right hamstring, the one that had the “mild hamstring strain” three years earlier, fails me once and for all. Season over again. Career soon to follow.

The Lighthouse Diagnostic Imaging Center reports its findings:

There is a complete tear of the contouring biceps femoris semitendinosus from its origin at the ischial tuberosity. The fluid-filled defect is appreciated well on axial images 11. The semimembranosus component is intact. The torn tendon is retracted slightly greater than 2cm as next seen on axial images 14. There is a mild amount of surrounding peritendinous edema. There is intramuscular and perifascial edema primarily involving the semitendinosus muscle. The more distal biceps femoris component of the tendon is thick and low signal. This suggests chronic tendinosis and prior injury.

Comparison with large field of view images of the pelvis from November 2007 confirm chronic right-sided hamstring tendinosis with tendon degeneration or partial tearing affecting the biceps femoris semitendinosis on the prior examination. There is chronic partial tearing involving the adductor longus muscles from the pubic symphesis [

sic

]

bilaterally

, with greater involvement on the left. The distal fibers of the rectus abdominous [

sic

] are intact. There is fluid in the symphysis pubis with secondary cleft extending along the right aspect of the symphesis [

sic

]. This does not appear to be an acute injury.

I go back to Vail for another PRP injection and lie on my face as one more needle pushes down into my soul.

Not an acute injury. Both groins already torn. Both hamstrings already torn. Both hips already torn. The hamstring that had bothered me for years was torn from its attachment the whole time, and no one ever told me. It had never healed from the rehab or the injection or the off-season or anything. It was ready to blow.

I go back to Vail for another PRP injection and lie on my face as one more needle pushes down into my soul. I start the maddening rehab process once again, lying around the training room and trying to figure out why it happened. Was it the Toradol shots? All the anti-inflammatories and painkillers? My diet? Was it the creatine? Poor treatments of my chronic hamstring injury? Poor health care in general? The steroid injection in the ischial tuberosity three years earlier? Was it the hamstring overcompensating for a weak groin? My weight gain? A weak core? Fatigue? Was it my mind? Fate? God? No. None of it. It is football. I play football for a living.

I lie supine on a back corner training room table and watch a tide of poison molasses roll over our team. I can feel the life being sucked out of us. I stay at home while the team travels to Carolina and gets rolled. That sets up a home game against the lowly Bills in week 16. It’s all too easy: too perfect. Win and we’re in. I stand bundled up on the sidelines in the frigid Colorado winter and watch our season swirl down the drain. We are powerless to stop it. We lose 30–23 to a chorus of lecherous boos, setting up a week 17 matchup in San Diego against the surging Chargers. I go along on that trip to support the guys. But we don’t even need to show up for that one. It’s preordained. We get steamrolled. Our season is over.

A few days later Mike Shanahan is fired as head coach of the Denver Broncos. Not long after that, I am fired as backup tight end/special teams player for the Denver Broncos. Look, Ma, I’m nothing.

* * *

Cut by the Broncos after the 2008 season, a broken-down and aging Jackson walked a razor's edge by turning to PEDs in hopes of prolonging his career.

A week after being cut, I fly back to Denver to clean out my locker and say goodbye to my friends who work for the team. All of my teammates are gone for the off-season. I’ll never see them again. When I came to Denver, I came alone. All players do in one way or another. The Bronco organization was my lifeline. They were very good to me. I love them. I want to tell them how I feel about my time there. But I don’t have the words.

All I can think about is Josh McDaniels not calling me back. I want to run into him in the parking lot. I won’t need any words for that. I have a bone to break with him. But he’s in Indianapolis for the combine. Lucky Josh. Not that I don’t understand his indifference. He’s 32 years old. He’s just suicide-squeezed his way into the head coaching position of one of the NFL’s most venerable institutions, taking over for a future Hall of Fame coach who controlled the entire operation from top to bottom. The last thing he wants to do is waste his time explaining to a backup tight end why he doesn’t fit into the plan.

I sit down in my locker for the last time. It was always a bit out of sorts, full of clothes and shoes and tape and gloves, notebooks and letters and gifts. Do I even want these cleats? These gloves? These memories? Yes. I fill up my box. Six years as a Denver Bronco. Six more than most people can say. Still feels like a failure, though. So this is how the end feels? Standing in an empty locker room with a box in my hand? Yep. Now leave.

Desperate times, you know the saying. I reach out to a connection I made a year earlier and acquire a supply of human growth hormone, HGH. The drugs come in the mail in a package stuffed with dry ice. I half expect to see the feds storm out of the bushes, guns blazing, as I pull the box off my front porch.

I get home and call my agent, Ryan. He knows that my prospects aren’t great. I am an undersized tight end with injury problems and I am pushing 30. I need to find a team that wants a player with my skill set and won’t be turned off by the injuries. That won’t be easy, especially because the most recent one hasn’t healed. What I couldn’t convey honestly to our trainer I can to Ryan. There is a problem—a deeper problem—that’s affecting my body. It’s not simply that my hamstring is s---. The entire functional movement of my body is off. I can feel it with every step I take. Something is amiss.

Ryan sets me up with a biomechanics specialist/physical therapist in San Diego named Derek Samuel. Ryan thinks I’ll get along with him. He’ll assess my situation and we’ll go from there. But I’m afraid this won’t be enough. Desperate times, you know the saying. I reach out to a connection I made a year earlier and acquire a supply of human growth hormone, HGH. The drugs come in the mail in a package stuffed with dry ice. I half expect to see the feds storm out of the bushes, guns blazing, as I pull the box off my front porch.

But no feds. Just me and another needle.

It comes with very little guidance as to the quantity and regularity of the shot. I have a conversation with my supplier and he tells me how to do it. Other than that I’m on my own. I will tell no one what I’m doing. I go to the store and buy syringes and start injecting it in my stomach immediately. I am paranoid about every aspect of this decision. I’ve never used performance-enhancing drugs. Haven’t ever even seen them. I take pride in my natural ability and I don’t want to taint it. I don’t want to test the karmic winds. But I also don’t want to taste the death of my football dreams, not like this.

I pack up my Denali and head over the Rocky Mountains, the vials of HGH stuffed in an ice-filled cooler. My time with the Broncos is up. That’s for sure. The rest of it will reveal itself eventually. But all men must move along. And they must do it with the feeling that they have left business unfinished, relationships unformed, opportunities untaken. I played for the Denver Broncos. I achieved my dream, which confronted me with a naked truth: the dream has been won, and it is not enough. I leave for San Diego to revive the dream, to give it the fresh air it needs, so that I can leave the game on my own terms.

Nate Jackson played six seasons in the NFL. SLOW GETTING UP is his first book.