We Compete Against Ourselves

Sherman’s fourth-quarter interception led to a field goal that put the Seahawks up 22–3 on the way to a definitive 29–3 win over the division-rival Niners. (Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated)

I’m no golfer.

But I do own a set of clubs. I’m taking lessons, and I’ve hacked away on five or six occasions with my teammate Brandon Browner. On Tuesday, after we beat the 49ers 29-3, Brandon and I planned to play few holes at our local public course in Renton, but Brandon couldn’t make it, so I went alone. I’ve played football, basketball and baseball, but there’s something special about golf. Maybe it’s the technical nature of the game, how controlled you have to be, and how you can never be perfect. I am reminded, this week, of why golf is so much like playing pro football.

Now, we’ve just beaten the 49ers—a team that our doubters believed to be the class of the NFL until Sunday. This week we’ll see the 0-2 Jaguars, a heavy underdog in the betting world who could be down to their backup quarterback for the second week in a row. You can already imagine the questions we’ll face in the locker room this week, and the answers we’ll recite.

How do you avoid a letdown?

“You take every game one at a time.”

Well I have the page now, so let’s go deeper. The real trick to avoid hangovers after big wins in football is the same mentality that applies to golf, my new hobby, and track and field, my old love. In the minds of the men in our locker room on the day of the loudest sporting event in NFL history, we didn’t play the 49ers, or Jim Harbaugh, or Colin Kaepernick, or Anquan Boldin. We were playing the Seattle Seahawks. When you play at a high level, a game has nothing to do with the opponent; it has everything to do with us. That’s what makes us different, and that’s what makes playing in the NFL special.

I can still remember my worst event in track at Stanford before I left the sport as a sophomore: the 110-meter hurdles. It was a difficult transition, going from the fluidity of football movements to the repetitions of the hurdles. But I do remember my personal best time—14.4 seconds. I don’t remember where I was, or who I was running against, but I’ll never forget the time.

The mindset must be the same, whether you’re covering Anquan Boldin or a Jaguars rookie.

That’s the way we look at football games. We remember two things: the final score, and whether we met our defensive goals. No matter who we play, we want to accomplish certain things in the red zone, certain things on third down and achieve a certain number of turnovers. It doesn’t matter if I’m playing against Boldin, Cecil Shorts or Andre Johnson—when I go up there, I want to dominate whoever is in front of me. There are certain standards we have on our defense that must be upheld.

Admittedly, I didn’t always feel that way about football. In college, you get up for the big games—Oregon, USC, Notre Dame. It’s a rivalry mentality. All over campus, everyone is more involved in those games, and the environment can dictate your mood. Even when I entered the league, when I was only playing special teams for the Seahawks as a rookie in 2011, I wasn’t necessarily jacked for every game. But I heard the message every day, and when I became a starter I understood the mentality of coach Pete Carroll and his staff: Every one of us is competing against ourselves. Get better at something, whether it’s a small thing or a huge thing. Nobody’s ever had a perfect day, but you’re trying to get there.

Of course, when the games come you have to study film and prepare for the tendencies of the opposition. I dived into Jags film this week just as hard as I did 49ers tape a week ago. You want to know who’s having big games, and you want to keep that guy from having a big game. Additionally, you have to be aware of the men around you—their strengths and weaknesses and how we can help one another. But you can’t overthink the guy across from you or the guy next to you. Great players on great teams are able to trust in the game plan the coaches come up with and trust in their teammates to do their jobs. Whether its stopping one guy or another, we trust in that game plan and we focus on executing it perfectly.

No matter who we play, we remember two things: the final score, and whether we met our goals.

You might ask, how can you hold a Boldin in the same regard as a less-experienced receiver on another roster? How does a rookie like Denard Robinson inspire the same effort and tenacity as a Calvin Johnson? It’s because I owe Denard and every other NFL receiver that same level of respect, simply for the fact that he’s an NFL player. This is the mountaintop of our sport, and if you ever disrespect that, it will be a long day for you.

The first time I ever played golf, I had no idea what I was doing. I knew enough to not look stupid. With borrowed clubs at a course in Canada in June I took a few embarrassing swings that ended in the woods or the heavy stuff. I was all over the map. Then, out of nowhere—CRACK. I connected with a driver and sent one 225 yards straight down the fairway on a par 4. For months I’ve been trying to duplicate that feeling. At that point it didn’t matter what the rest of my group had done—I was no longer playing against anyone but myself.

That’s how you never overlook anybody.

* * *

We Compete Against Ourselves

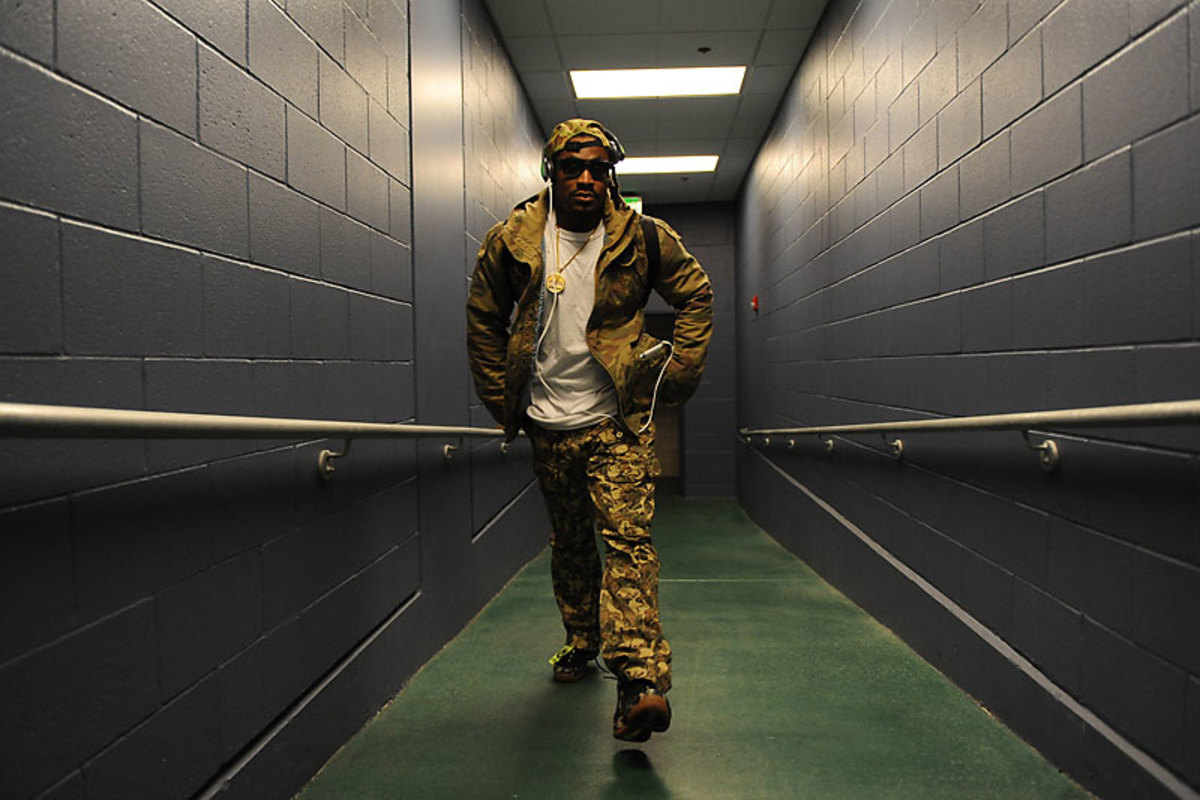

SEAHAWKS SCENES: Rod Mar, the Seattle team photographer, captured the mood at CenturyLink last Sunday. Here, Marshawn Lynch went Beast Mode in the hallway. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

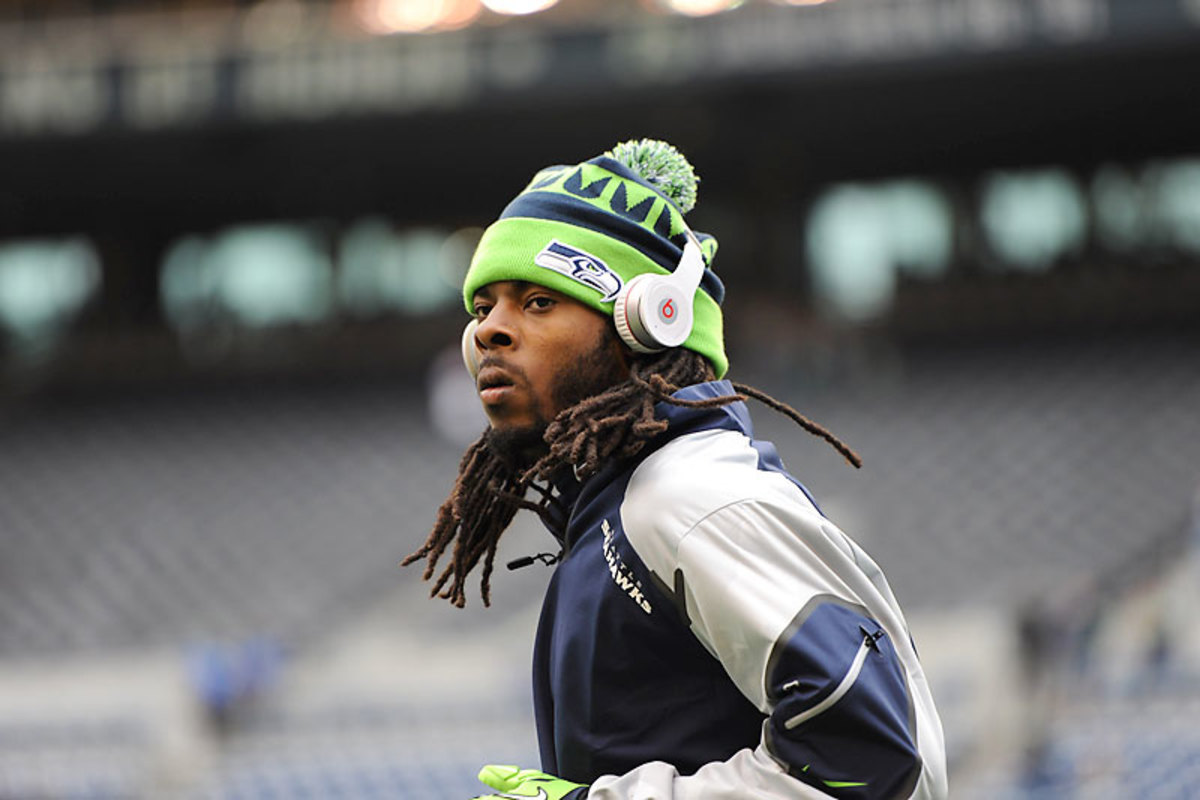

Richard Sherman found the pregame zone. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Brothers in arms: The NFC West’s two phenom QBs shared a hug before the game. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

The Seahawks were all in for the biggest game of the early season. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Sidney Rice prepared to run out . . . (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

. . . and greet a pumped up crowd of 68,338. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Indeed, the sound measured 136.6 decibels at one point, surpassing the previous Guinness mark for a sports event at a stadium. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Richard Sherman was everywhere. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Colin Kaepernick felt the heat all night and had by far his worst performance as a starter: 13 of 28 for 127 yards and a 20.1 rating. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

The sky boded ill for the Niners—and when it opened, it caused a long weather delay. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

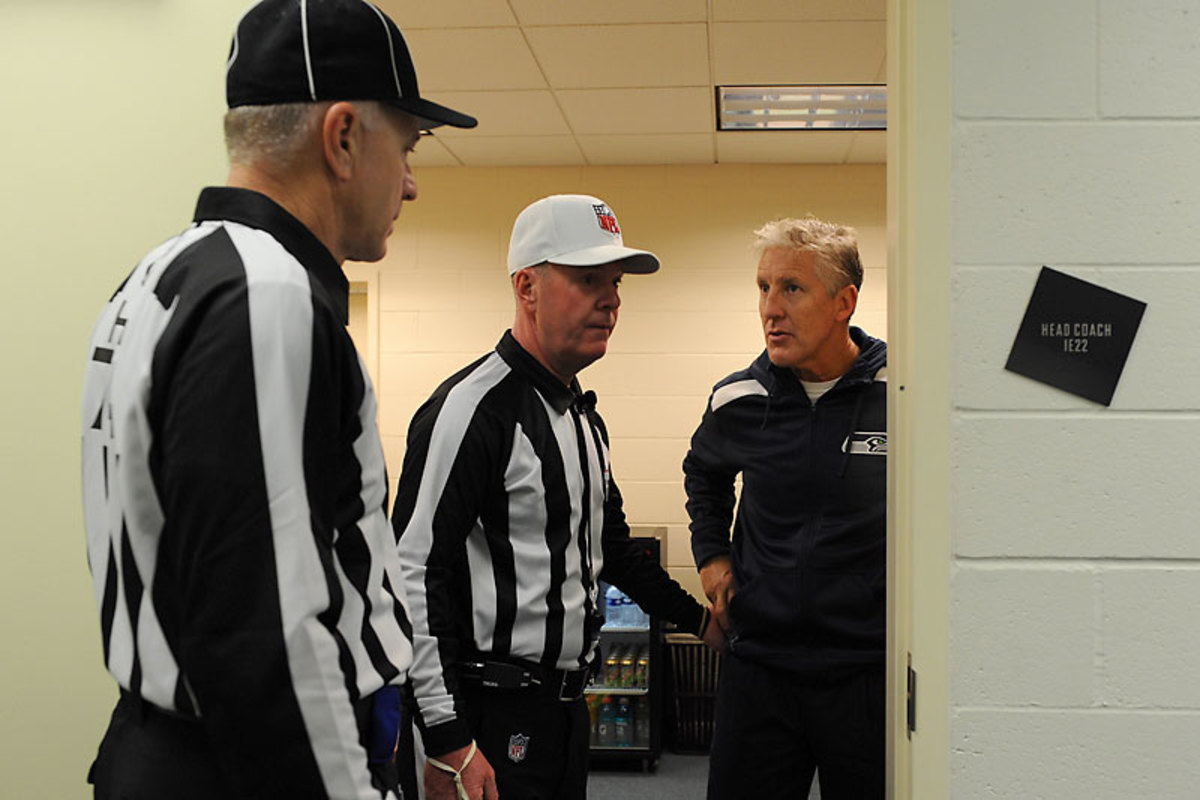

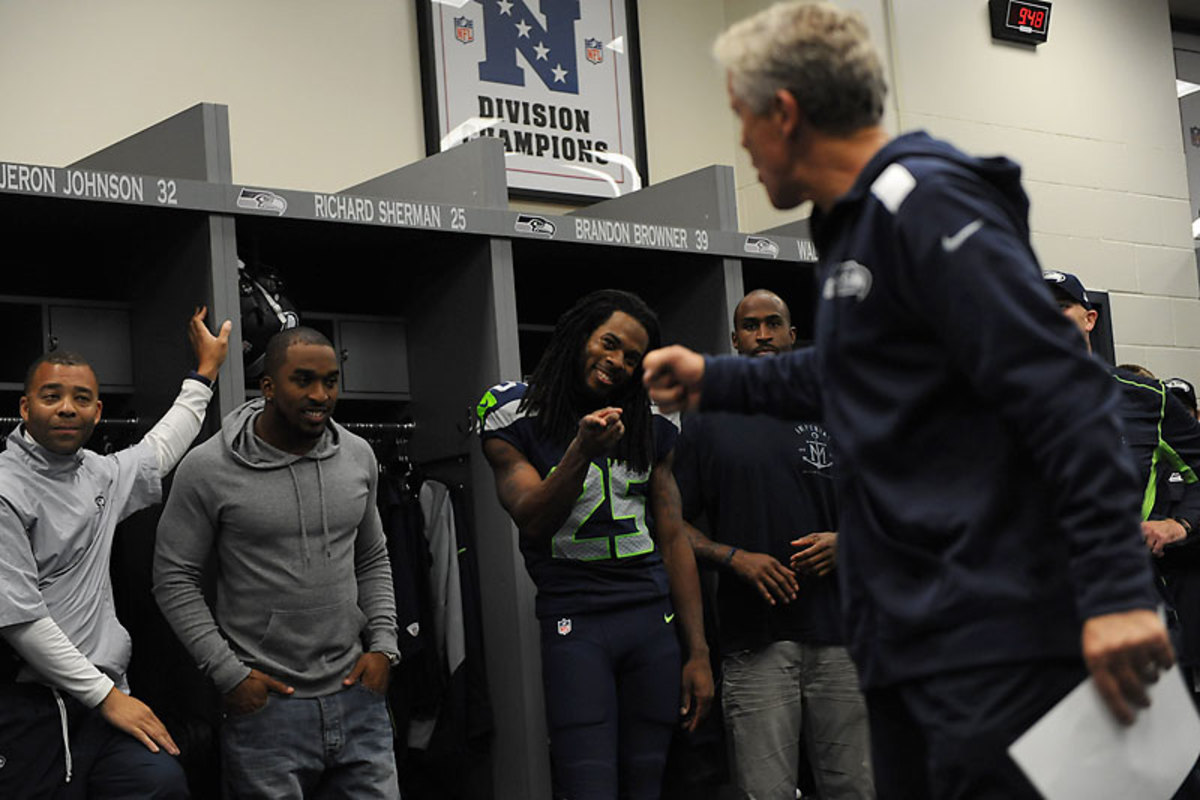

Pete Carroll had official business to handle. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

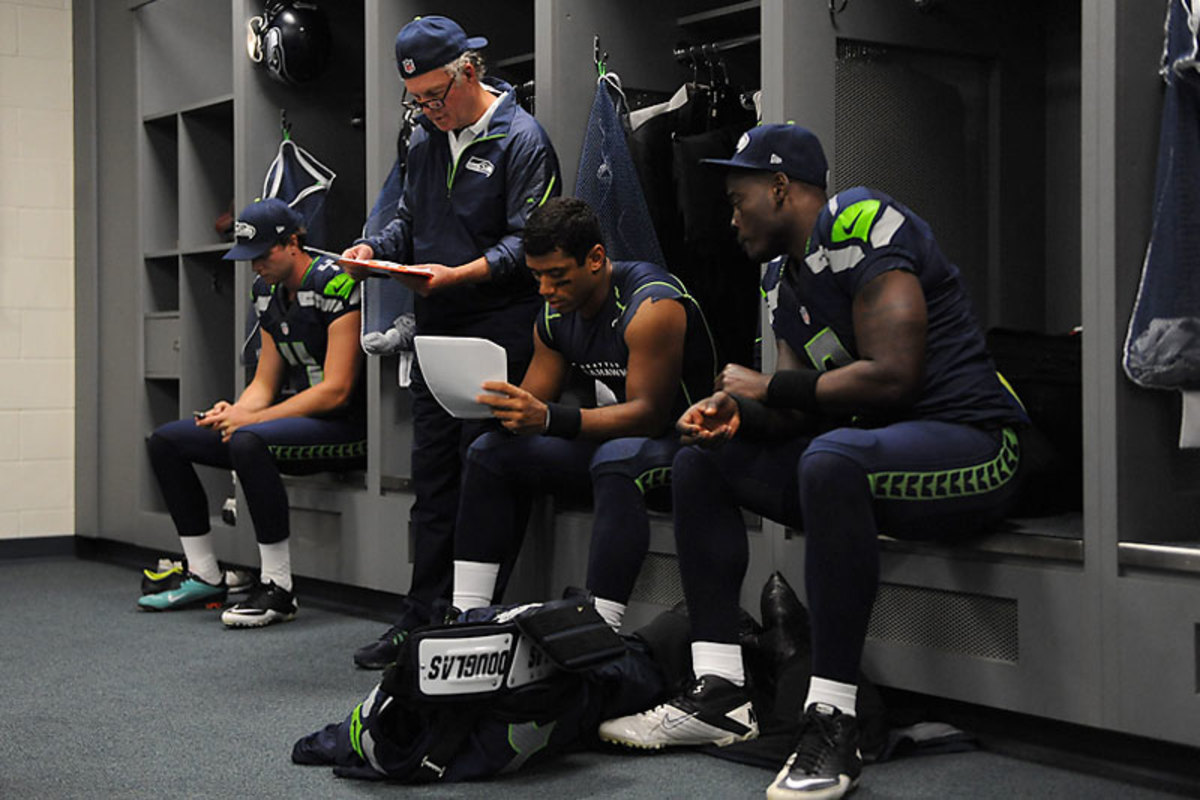

Assistant coach Tom Cable drew up plans for his charges. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Russell Wilson, always studying. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

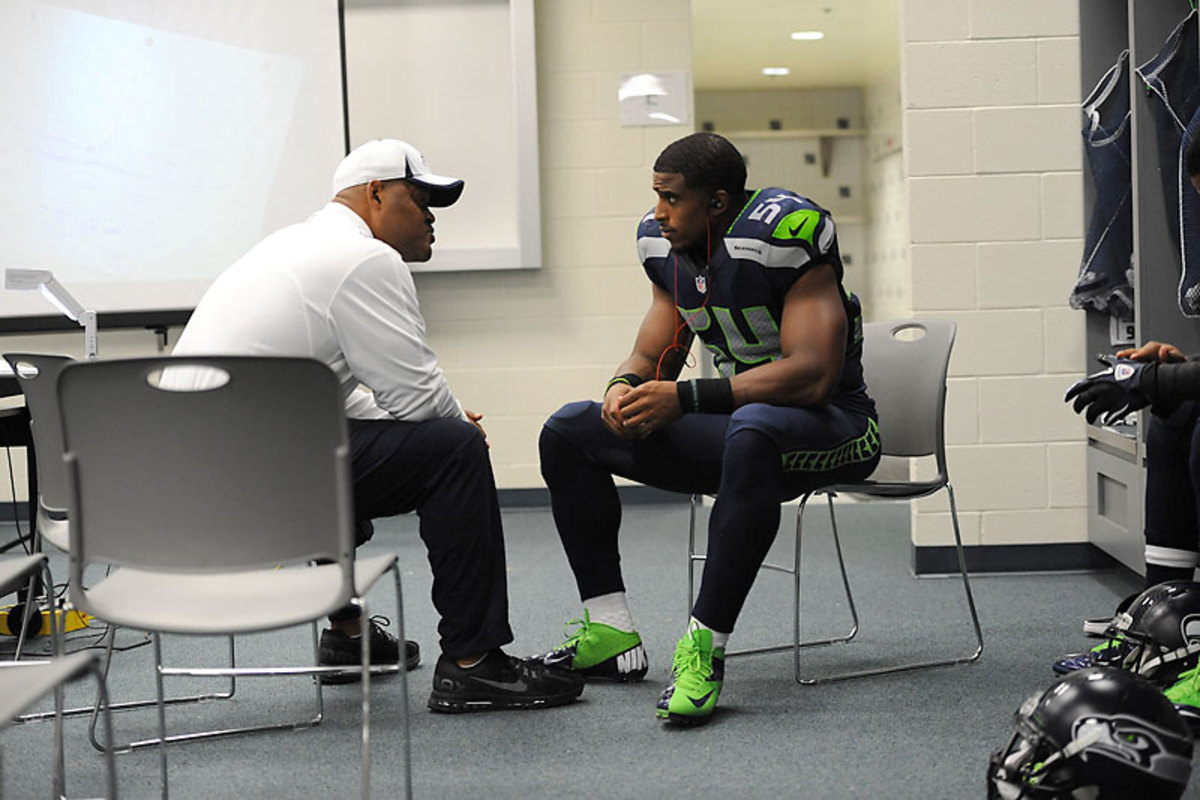

Linebackers coach Ken Norton Jr. huddled with Bobby Wagner. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Owner Paul Allen spent face time with the coach. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Lynch delivered, with 98 hard-earned rushing yards and three touchdowns. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

The harried Kaepernick threw three interceptions—as many as he had all of last season—and lost a fumble. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Sherman handled Anquan Boldin for most of the night but was covering Vernon Davis on his interception. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Why not celebrate a pick against your biggest foes? (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Jim Harbaugh vs. Pete Carroll is shaping up to be a classic NFL coaching rivalry. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Running back Robert Turbin shared the crowd’s joy. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Carroll and the Seahawks got their point across to the Niners and football nation. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Coach and quarterback reveled in the statement win. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Sherman and Carroll, happy bros. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)

Rookie tackle Michael Bowie found some quiet time. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated)