How Cover 2 Became an Endangered Species

Pittsburgh fans entered Heinz Field thinking they’d see a familiar barrage of blitzes last Sunday night. They did, but from the unexpected team.

The Bears, long known for having the NFL’s consummate vanilla Cover 2 defense, sent additional rushers after quarterback Ben Roethlisberger on 27 plays. Often it was inside linebackers D.J. Williams and/or Lance Briggs (who both do well in this capacity), but safety Chris Conte also came off the edge a few times. Most intriguing is that 22 of the 27 blitzes occurred on first or second down, suggesting that additional pressure was the backbone of Chicago’s game plan.

No, these aren’t your father’s Cover 2 Bears.

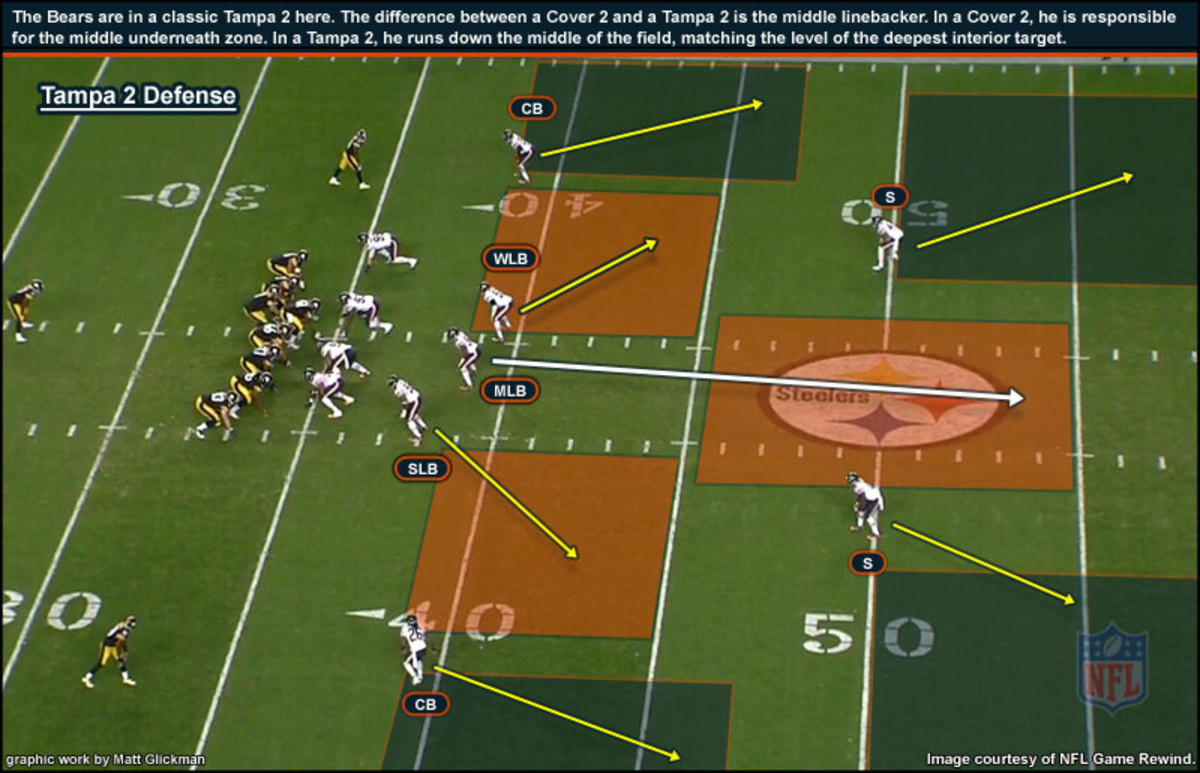

A quick refresher: Cover 2 is the double-high safety zone that has served as the foundational scheme for roughly half of the NFL for nearly two decades. It had a meteoric rise in the ’90s when Buccaneers coach Tony Dungy and defensive coordinator Monte Kiffin added a wrinkle, known as Tampa 2, by extending the coverage duties of the middle linebacker.

As reliable as it was simple, Tampa 2 worked as long as the defense had fast linebackers and a viable four-man pass rush. Not anymore. Last Sunday’s game at Pittsburgh was a perfect illustration of how a scheme slowly dies. The Bears played two high safeties on just 30 of 65 snaps. According to the War Room research staff for the NFL Network’s show Playbook, the Bears have played two high safeties on less than 40% of their snaps.

This isn’t because of the new coaching staff. Defensive coordinator Mel Tucker, formerly of the Jaguars, is a longtime Cover 2 acolyte, just like his predecessor, Rod Marinelli, and former Bears head coach Lovie Smith. More and more, Marinelli and Smith drifted away from Cover 2 over the past two season seasons, and Tucker has only continued that trend.

The Lions, another classic Cover 2 team, are also trending away from the scheme. Detroit coach Jim Schwartz has always favored a gap-shooting, four-man rush in front of seven race-to-the-ball defenders. But lately Detroit’s defense has had the imprint of its coordinator, Gunther Cunningham, who champions for more schematic diversity and proactive aggression.

Cover 2 has been on the decline league-wide for a few years now. It’s not just about defenses calling more blitzes. Even defenses that can generate pressure with four rushers—which Detroit does, and Chicago, though struggling with it this season, aims to do—are choosing to play different coverages. The Bears, even when not blitzing, have played single-high safety on 70% of their snaps. The Lions have gone single-high 55% of the time. (And not just because they loaded the box against the Vikings’ Adrian Peterson in Week 1. The Lions actually used more single-high looks against the Cardinals Week 2.)

Clearly, Cover 2 is dying. There are four key reasons:

Holes

Every zone coverage has holes. (If there were a zone coverage that didn’t have holes, defenses would play it on every snap.) Cover 2, with its static back seven defenders, has obvious holes. (Mainly, the deep-intermediate outside window above the corners and in front of the safeties, and the seams beyond the linebackers and in front of the safeties.) As the scheme became more prominent, offenses naturally focused more on exploiting those holes.

More 3-WR sets

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, offenses typically used three-receiver sets only in passing situations. Thanks to rule changes and better quarterbacking, virtually every down in today’s NFL can be considered a passing situation. Collectively, NFL offenses played three-wide 50% of the time last year. That third receiver can be a matchup nightmare for a traditional Cover 2, because in a lot of instances strict zone principles dictate that a linebacker is the only defender who can account for the slot man. The tight end, a position that seems to get more versatile and athletic every time a new guy enters the league, poses similar problems. Cover 2 defenses responded to this by playing more man concepts with their nickel slot corner, which led to deviations from the classic zone concepts.

Quicker passing attacks

Coinciding with the increased use of three-receiver sets has been the rise of three- and five-step timing in the passing game. That’s not surprising. More receivers typically means wider spread formations, which means a horizontally-stretched defense. That makes passing lanes easier for quarterbacks and receivers to identify before the snap, enabling the ball to come out quicker. This nullifies the four-man rush. A Cover 2 without an effective four-man rush is a dance party with no music.

Sophisticated quarterbacking

Thanks to advances in the passing game, quarterbacks are more equipped than ever to punish a predictable defense. And to put it scientifically, there are so many quarterbacks who are insanely talented. Look at the two in Sunday’s Bears-Lions game. Jay Cutler and Matthew Stafford would both fall somewhere near the middle in most people’s league-wide QB rankings. Yet both have sensational arm strength and the ability to make late-progression throws under pressure. Quarterbacks like this are hard to beat physically, so defenses must find ways to beat them mentally. You can’t do that playing the same static zone (Cover 2) look on every snap.

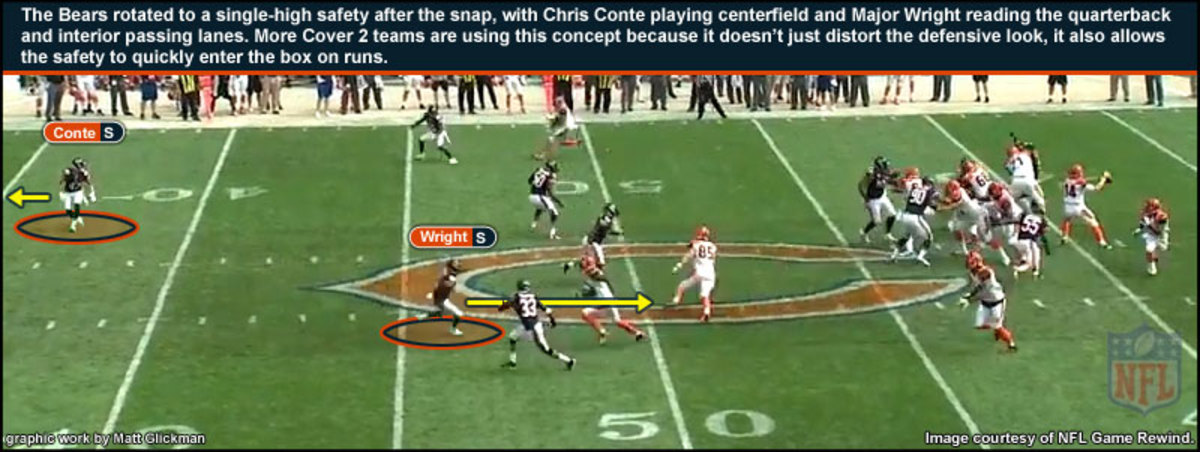

How have traditional Cover 2 units evolved? These days, zone-based defenses like Chicago and Detroit are using more single-high coverages. They’re filling their safety position with versatile athletes, making the free and strong safety roles interchangeable. For the Bears, Chris Conte and Major Wright both are comfortable maneuvering through traffic in the box or patrolling in open space in the secondary; the same goes for the Lions’ Louis Delmas and Glover Quin.

Most Teams are still showing a lot of two-deep looks, but upon the snap, they’re rotating to single-high concepts. One increasingly popular coverage this season has been single-high robber.

Post-snap coverage rotations can be highly effective because route combinations that work against a single-high coverage rarely work the same way against double-high coverage, and vice versa. And even if the offense identifies the coverage, there’s still value in the rotation process because movement by the defensive backs reshapes voids in the zones. The transforming looks can be a lot for the offense to process, making it harder for the quarterback to get the ball out quickly. This brings the four-man rush back into the equation.

If you’re not convinced that Sunday’s Lions-Bears contest will showcase the demise of Cover 2, then check out the Cowboys-Chargers game instead. The Cowboys this past offseason wanted to install a zone-base scheme, so they hired the godfather himself, Monte Kiffin. So far, Kiffin has played Cover 2 on just 24.2% of his opponents’ pass attempts.

THURSDAY NIGHT PREVIEW

Tavon Austin

Rams offense vs. 49ers defense

St. Louis’s transition to being a flex, spread offense has been bumpy so far. After an encouraging Week 1 home win over Arizona in which expensive free-agent pickup Jared Cook caught seven balls for 141 yards and two touchdowns, the Rams have fallen into big first half deficits each of the last two weeks and been unable to establish any sort of rhythm.

That said, against the Falcons’ very average four-man rush in Week 2, quarterback Sam Bradford and his receivers moved the chains out of 3 x 2 empty sets in their hurry up down the stretch. Early on last Sunday, Monte Kiffin’s normally conservative Cowboys defense successfully blitzed those 3 x 2 empties (a smart tactic, because there’s no one in the backfield to pick up the additional pass rushers) and made the Rams’ passing game frenetic. Eventually, the Cowboys realized they could generate pressure with just four rushers, which they did on most of their six sacks of Bradford.

The absence of right tackle Rodger Saffold was a factor, but every Rams lineman struggled individually against the bull rush (including left tackle Jake Long, who has been solid this season but was pancaked a few times by DeMarcus Ware).

Can the 49ers generate the same sort of pressure? They have a physically powerful defensive front, not just with Justin Smith but also versatile outside linebacker Ahmad Brooks. However, the indefinite absence of Aldon Smith could prove to be a deathblow for a defense that rarely blitzes and lacks depth on the edges (top backups Dan Skuta and Corey Lemonier have played all of 13 combined snaps this season).

When the pass-rush tailed off down the stretch last season, the 49ers cornerbacks, even with the scheme’s foundational double-safety help over the top, had trouble sustaining man coverage. The St. Louis wide receivers may not be polished enough to capitalize on this—Chris Givens and Tavon Austin are primitive route runners; Austin Pettis is improving but remains too inconsistent; Brian Quick remains a mystery and not in a good way. Coverage is a concern for the Niners moving forward.

In this particular game, expect Rams offensive coordinator Brian Schottenheimer to center his passing attack around Jared Cook inside. Normally, Patrick Willis covers tight ends in San Francisco’s man schemes. With Willis battling a groin injury, Cook may find himself matched against backup linebacker Michael Wilhoite.

Frank Gore

49ers offense vs. Rams defense

Any offense that scores just 10 points over two games has multiple problems to address. The Niners would be wise to start with their running game. It produced just 90 yards on 34 attempts against the Packers in Week 1. No one noticed because Colin Kaepernick and Anquan Boldin were lighting up the skies. In Week 2, the running game yielded 13 yards (excluding a few Kaepernick scrambles). This time, people noticed because San Francisco’s receivers were unable to unshackle themselves from the Seahawks’ stingy corners.

When those receivers had similar problems in Week 3 against the Colts, Greg Roman and Jim Harbaugh didn’t try to reestablish offensive control by hitting the ground, even though Frank Gore looked spry (82 yards on 11 carries) and San Fran’s man-blocking O-line was actually moving opponents for the first time all season. Instead, the Niners relied on Kaepernick, whose scrambling was bottled up by the fast and aggressive downhill play of Indy’s safeties and linebackers. The second-year quarterback played wide-eyed on far too many dropbacks in the pocket. If Kaepernick’s initial read isn’t open, his eyes often go immediately to the pass rush. You can’t build a consistent offense that way.