Remembering Bum Phillips, the unsung defensive innovator

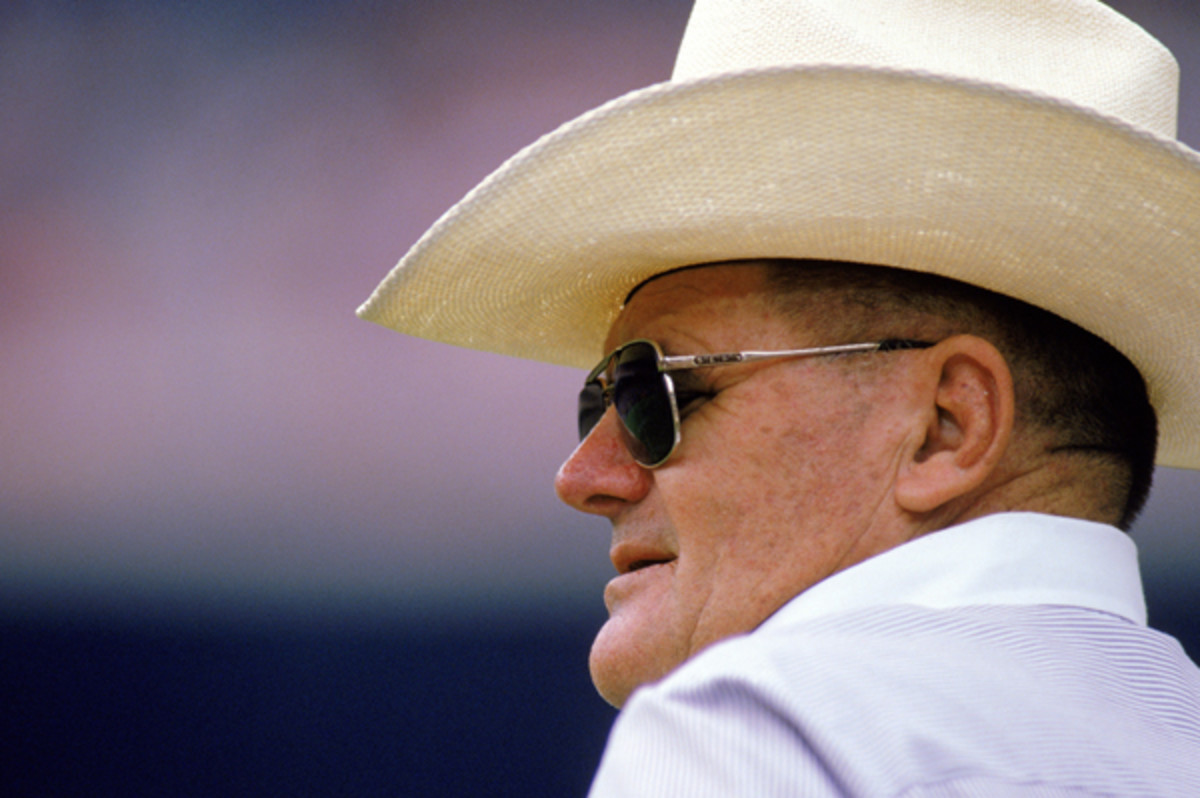

O.A. "Bum" Phillips brought much more than a cowboy hat and colorful quotes to the game of football. (Rick Stewart/Getty Images)

There is a temptation when looking back on the life of Oail Andrew "Bum" Phillips to view him simply as a folksy coach with a 20-gallon hat and a colorful turn of phrase. And through that narrow prism, Phillips qualifies -- this is the man who once said of Don Shula, "He can take his'n and beat your'n and take your'n and beat his'n." And yes, Phillips forged a series of unforgettable images with his cowboy attire on the sidelines when coaching for the Houston Oilers and New Orleans Saints from 1975 through 1985. But one would be mistaken to assume that Phillips, who passed away on Friday at the age of 90, was all hat and no cattle.

Phillips spent time as a college assistant from 1958 through 1966, moving to the American Football League when Sid Gillman hired him to be the San Diego Chargers' defensive coordinator in 1967. He stayed there through 1972, did a year with Oklahoma State in 1973, and reunited with Gillman on the Houston Oilers' staff in 1974. He replaced Gillman as the Oilers' head coach in 1975, going 10-4 in his first season and working his magic with a team that had won a total of nine games in the previous three years. Much has been said and written about Phillips' ability to bring players together and instill a common belief system with different franchises, but there was far more to his success than the intangibles. Bum Phillips was a brilliant defensive innovator and strategist.

The two common concepts Phillips is often credited with bringing to football in general and the NFL in particular are the numbering system for defensive fronts and the professional version of the 3-4 defense. Phillips worked for Paul "Bear" Bryant at Texas A&M in 1958, and it was there that the current numbering system (one-technique, three-tech, five-tech, etc.) became common nomenclature.

"After coaching for a number of years and always trying to find something that would make football easier to understand for the average player, I came upon a system of defensive numbering that has proven very valuable to me since then," Bryant wrote in his book, Building a Championship Football Team. (via Trojan Football Analysis). "In the past, I have used many different defenses. I always employed the technique of giving each defense a 'name.' Most of the time, the name had little in common with the defense, and this confused rather than helped the players.

"After discussing the possibility of the numbering with my own and other college and high school coaches while at Texas A&M in 1956, I finally came across a feasible plan for numbering defensive alignments. I must give credit to O.A. Bum Phillips -- a Texas high-school coach -- for helping work out the solution as he experimented with the numbering system with his high-school team."

College and NFL coaches were working to make their fronts more diverse, from the old five-man fronts to the Tom Landry-conceptualized 4-3 defense to the first strains of the 3-4 defense as a base concept. As with most NFL innovations, the 3-4 gained traction in college football, and its primary practitioners took the 3-4 with them to the pros.

Phillips and Chuck Fairbanks are the two coaches credited with bringing the 3-4 to the NFL as a pure base defense. There had been elements of it before -- as SI's Paul Zimmerman pointed out in a 1997 article, the Oakland Raiders moved defensive tackle Dan Birdwell around to different positions in the 1960s, and the Miami Dolphins of the early 1970s brought linebacker Bob Matheson in for certain defensive packages to enhance Bill Arnsparger's defense. But it was Phillips for the Oilers, and Fairbanks for the New England Patriots, who took that principle to the next level.

In an interview with the Houston Oral History Project in 2008, Phillips explained why he actually installed the 3-4 later in his time with the Chargers.

"The fourth year I was out there, we did not have enough defensive linemen to play four down people. So, I just went back and started working up a 3-4, which did our personnel good and we started playing it. And, of course, Sid, he didn’t think we could play it. He thought the people would just run the ball on you. I told him, well, that is the reason why Oklahoma uses it. They can’t run the ball on the 3-4. They might think they can, but they can’t. But the value that was gotten out of it was even greater. Because in pro ball, everybody had the same pass protection rules. Linemen on linemen, backs on the linebackers, and the center on the middle linebacker. That was everybody’s rule. Well, we had three linemen and two outside linebackers and we learned which way they were going to block, which backs. And we could choose which linebacker we wanted to rush to get just more rushers. So, I would give us a linebacker.

"Nowadays, everybody has done turning their line towards the most dangerous linebacker and they can get big men on big men and even your good linebacker. But in those days, it did not, and we hurt them bad with it until we got ready to play the season. [Then Gillman] came in and he said, 'I want to go back to the 4-3.' I said, 'Coach, we can’t play the 4-3.' He said, 'That is what I want to do.' So, we put the 4-3 in and Kansas City beat us, 45-7. We could not stop them with a shotgun. And we got far that year."

In Houston, Phillips had the most important thing to make it work -- the right players for his schemes. Nose tackle Curley Culp was the perfect interior road-grader, as he had been for the Hank Stram-coached Kansas City Chiefs (who also experimented with 3-4 ideas before they were au courant). Defensive end Elvin Bethea and outside linebacker Robert Brazile combined pass rush and dominant run-stopping ability from the right side, and Jim Young and Ted Washington were among those players who brought it from the left angle. It was believed that the 3-4 would be soft against the power running game, but Bum's Oilers didn't have that problem -- through the most impressive and contentious times in the old AFC Central division, that defense helped the team amass a 55-35 regular-season record over seven seasons. The subsequent frustrations against the Pittsburgh Steelers in the playoffs were more about Pittsburgh's greatness than any obvious flaw in what the Oilers were doing.

Phillips further explained the Houston 3-4 in a 1975 SI piece authored by Ron Reid.

"It makes more sense that you can defend against the pass better with eight people than you can with seven. And as for the rush part of it, it's just about as easy as with a four-man front because you can rush one of your linebackers. It baffles the quarterback because you can get so much more variation with eight people back there than you can with seven. Quarterbacks are also used to seeing a middle linebacker and reading their keys off him. Now with the 3-4, you come in with two middle linebackers, it messes the quarterbacks up and it messes protections up.

"Well, after playing it so many years in high school and college, I knew that when we put a nose man in there the center couldn't be a good pass protector because he's got to raise his shoulders after he snaps the ball. By then the nose man is by him. What it ends up doing is tying up three people because the guards have got to look out for the center."

You would hear Dick LeBeau, or Dom Capers, or Bill Belichick explain it fairly similarly in 2013.

Bum Phillips, seen here in 2011, always had time to give son Wade a few words about running a defense. (MCT via Getty Images)

In New Orleans, Phillips ran his trademark schemes, and gave Jim Mora's "Dome Patrol" defense -- regarded by many as the best 3-4 unit in NFL history -- a head start when he selected Hall of Fame linebacker Rickey Jackson in 1981. Phillips never had a winning season in New Orleans from 1981 through 1985, but he took over a defense that ranked 28th in points and yards in 1980 and had it in the top five in yards allowed from 1982 through 1984. He resigned in November 1985 and never coached in the NFL again -- content at that point to work on his ranch, assemble some estimable charities, and watch the ideas he helped create take hold through the following years.

His son Wade has been a fine defensive coach for more than three decades -- both with and without his dad -- and it could be said that anyone running a version of the 3-4 defense in the modern NFL is Bum Phillips' offspring to some degree.